As a historian of exchange, I am conscious that goods that travel long-distances, are shiny or unusual get all the glory: a lot of history is mundane, low-key and local.

Every now and again, though, the glittery, exciting things are important for a reason. A case in point comes from what I think are perhaps the most exciting findings in recent North American archaeology: glass beads, indisputably European, and manufactured in Venice, have been uncovered in pre-Columbian archaeological contexts in Arctic Alaska - thousands of kilometres from their point of origin, and crucially, before Columbus’s arrival in the Americas.

This is not merely a story about beads.

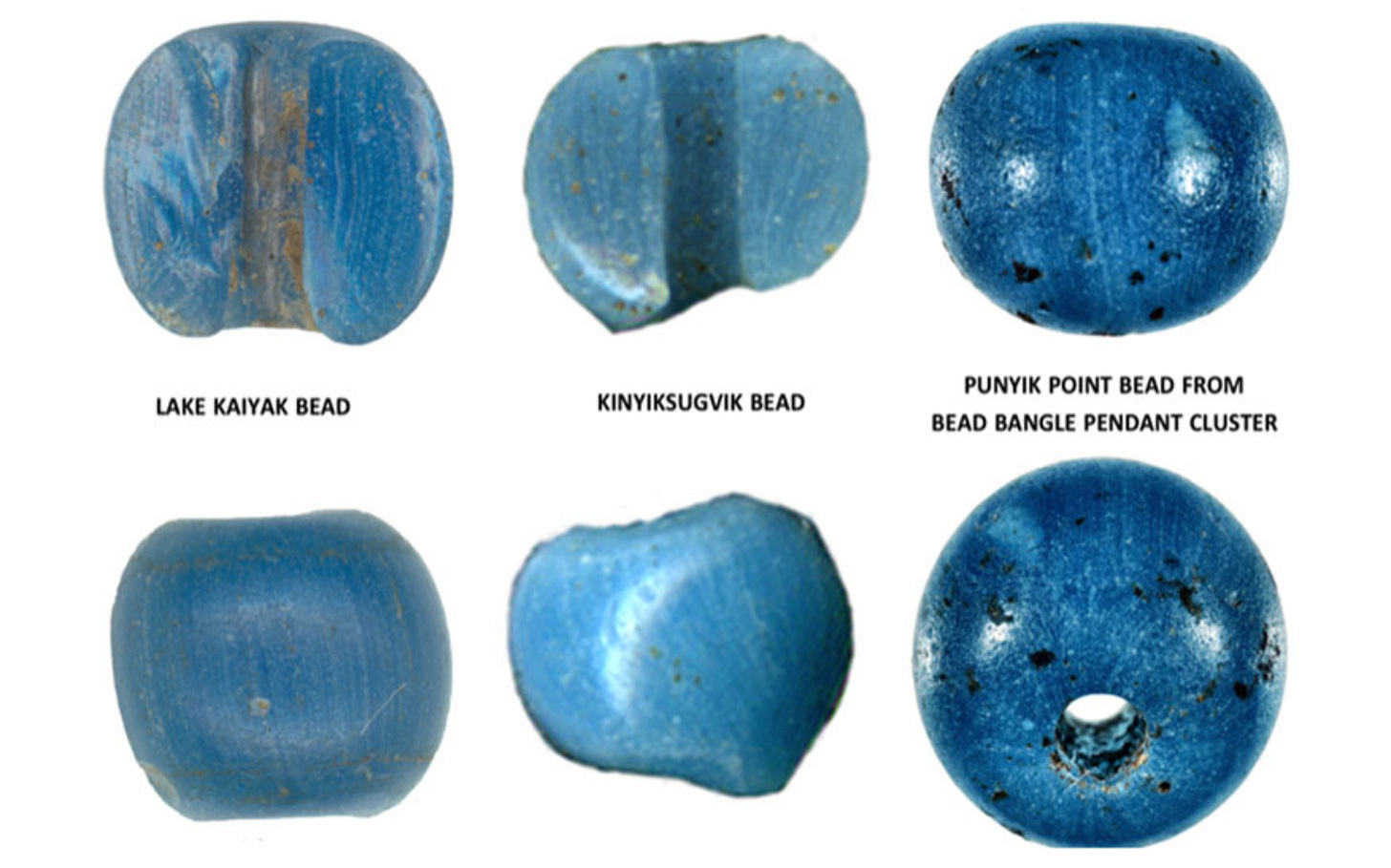

The findings, reported in American Antiquity by Michael Kunz and Robin Mills reveal the presence of so-called ‘IIa40’ glass trade beads - uniformly turquoise blue, slightly translucent, and finished by the a speo technique, a Venetian process that didn’t exist elsewhere in Europe in the Middle Ages.

I’ve been interested in glass beads for a long time. They provide important evidence of long-distance trade in what is now Siberia - for millennia. For example, at the Ust’-Polui site near Salekhard, on the Ob River, archaeologists have found beads dating to between the 1st century BC and 4th century AD. These beads - mostly monochrome, drawn glass - are believed to have originated in the Roman Empire or from Parthian production centres, making their way north via intermediaries in the steppe and forest zones. Likewise, excavations reveal evidence of large-scale and regular trade between the Byzantine world and parts of what is now Russian Baltic - around St Petersburg and Vologda.

For The Earth Transformed, I was struck by glass beads have been recovered in substantial quantities from sites in East Africa such as Shanga and Kilwa Kisiwani, dating from the 8th to the 15th century. These include Indo-Pacific beads, which were produced in South and Southeast Asia - particularly in India’s Deccan region - and reached the Swahili Coast via Indian Ocean trade routes.

At Manda (Kenya), excavations revealed glass beads in contexts dating to the 9th–10th centuries CE, often associated with Islamic trade goods and Chinese ceramics. These finds highlight the region’s deep integration into transoceanic commercial circuits centuries before Portuguese arrival.

So beads indicate trade and contact; and, depending how one interprets them, can show socio-economic status too.

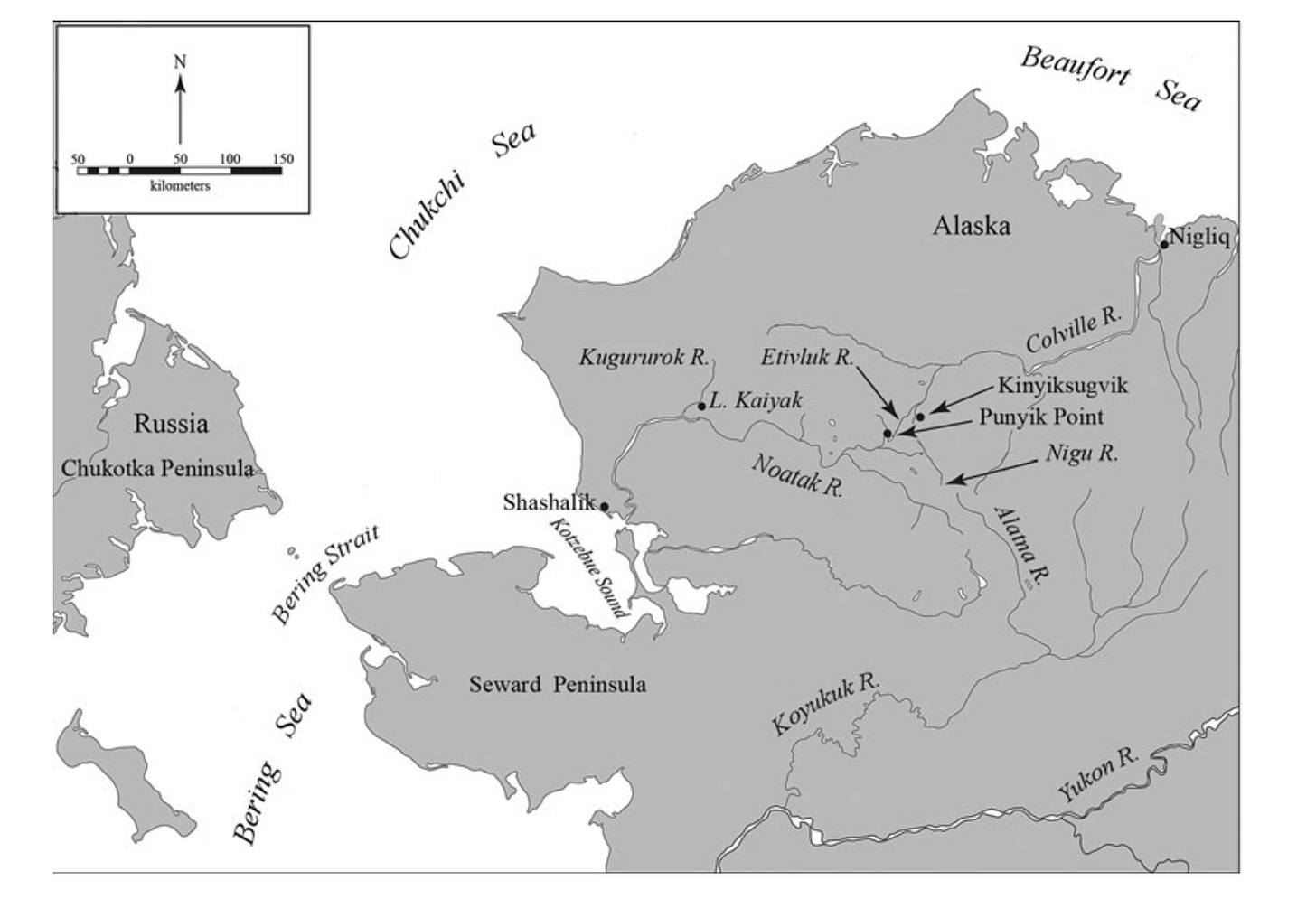

The Venetian beads in Alaska were found at three separate archaeological sites - Punyik Point, Lake Kaiyak, and Kinyiksugvik - well above the Arctic Circle, alongside native-crafted copper bangles and iron pendants. Radiocarbon dates associated with these finds cluster between AD 1397 and 1488, in other words before 1492, and well before Russian and traders of European descent reached southern Alaska.

If confirmed - and every piece of analysis to date points to the beads’ authenticity - this would represent the earliest physical evidence of European material culture in the Western Hemisphere, predating any transatlantic crossing - other than the well-known Viking finds from Newfoundland.

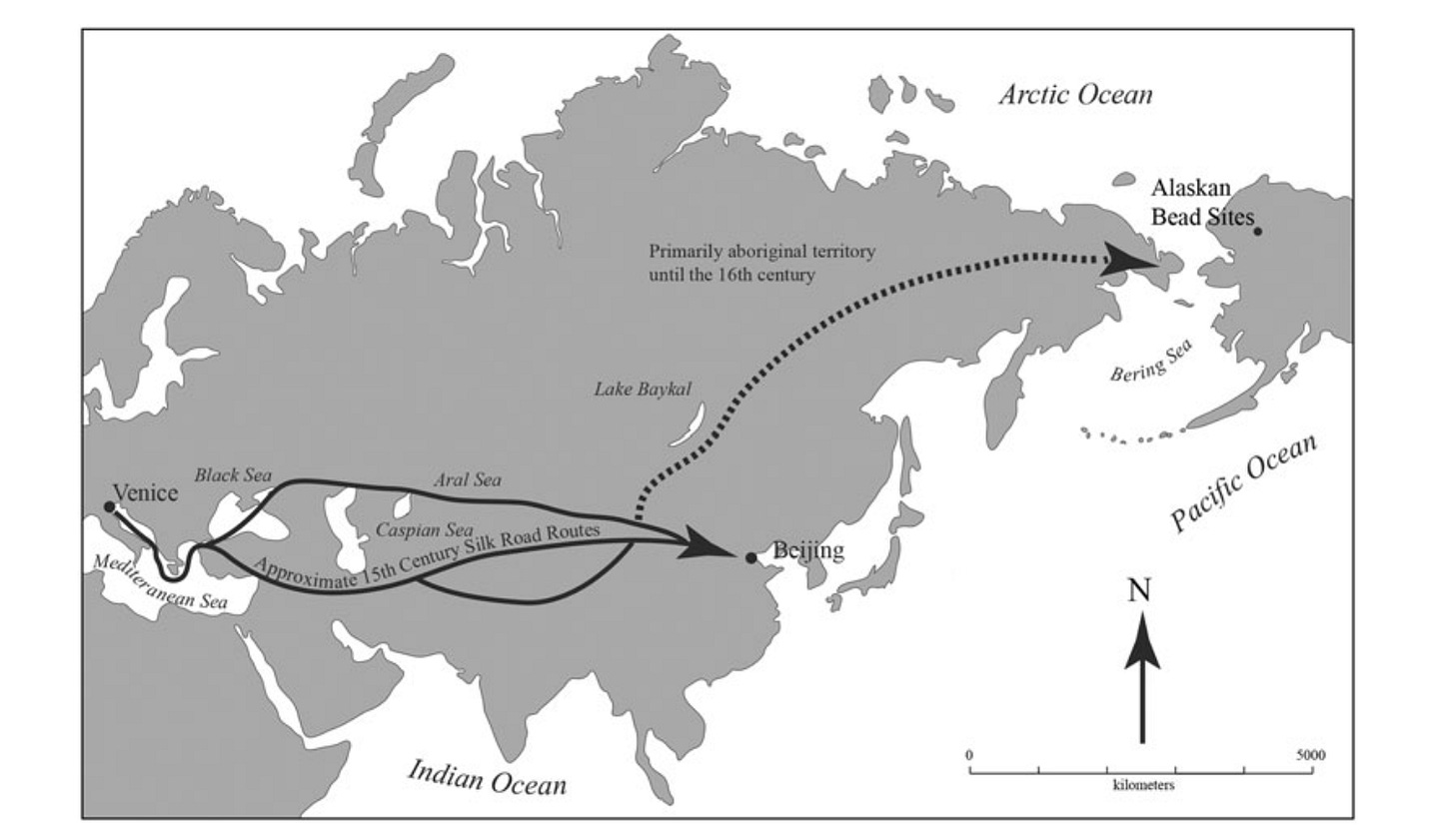

But what makes this discovery electrifying is the route the authors propose: these beads likely travelled overland across Eurasia, reaching northeast Asia via Silk Road trade routes and crossing the Bering Strait through indigenous social and commerical networks.

That’s a journey of over 17,000 km, stretching from the glassworks of Venice to Inuit communities in Arctic Alaska.

At first glance, the idea seems implausible, almost fanciful. But the evidence here is hard to dismiss. Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA) confirms the beads’ chemical composition matches Venetian production. Their typology places them in a category found at early colonial sites across the eastern seaboard of North America, but never before in Alaska. And the context? These weren’t beads lost by mistake at a later date or traded post-contact in recent centuries: they were sealed in undisturbed archaeological strata, associated with datable charcoal, faunal remains, and carefully twined plant fibres. So we can be as nailed-on certain as possible about the dates they were made, and buried.

So what are the implications?

First, this discovery demands a radical rethinking of global trade networks before the age of European maritime expansion. If luxury items from Italy could reach the high Arctic via Asia before Europeans crossed the Atlantic, then our assumptions about hemispheric isolation - still deeply embedded in education and public discourse—need urgent revision.

Second, this points to a far more dynamic and connected Indigenous world than often acknowledged. Arctic trading centres like Sheshalik, long seen as remote, were in fact nodes in vast overland networks stretching deep into Siberia and beyond. These communities were not passive recipients of foreign goods - they were active participants in exchange systems that spanned continents.

And finally, the timing matters. The period between 1400 and 1490 was a moment of intense change across Eurasia: the Ming dynasty was consolidating power; the Timurid Empire was at its height; and Venice was reaching its commercial zenith. This is the age of Zheng He’s naval expeditions, of Mongol legacy trade routes still pulsing with activity, and of European hunger for Asian goods. Into this matrix - long before Columbus set sail - went tiny glass beads, carried by merchants, exchanged at border outposts, handed from one community to another, until they arrived, improbably, in the frozen tundra of northern Alaska.

We often tell the story of globalisation beginning in 1492, with sails unfurled in the Atlantic. This paper asks us to reconsider that narrative. The world was already in motion. Threads of commerce, craft, and culture had already been spun. The question now is: how many more threads have we overlooked?

.png)

![512K Day: The Day the Internet Almost Broke [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/opera.png)