Living creatures aren’t the only things to be ravaged by epidemics. Computers, even Macs, can die prematurely when there are widespread manufacturing failures. I’d like to unearth a couple of mass graves from the past that have surely contributed to landfill around the world: capacitor plague and lead-free solder, and a recent problem with butterflies.

Capacitor plague 1999-2007

Capacitors or ‘caps’ have a chequered history. Acting as temporary stores of electric charge, they’re used extensively in most computer hardware and other equipment, such as ‘starters’ or ‘ballast’ for fluorescent tube lighting. They consist of conductive materials sandwiched with substances of low conductivity, or electrolyte. When manufactured to high standards they should last for 15 years or more, but cheap components are prone to overheating, electrolyte leakage, and in the worst case even fire.

With manufacturing driven to minimise the cost of components, some who procured supplies of capacitors have saved a few pence using cheaper sources. Many have turned out to be duff, so-called counterfeit capacitors: in the early years of this century, a series of fires in mainly industrial and commercial premises were blamed on catastrophic failure of strip light ballasts.

Computer motherboards and other components, including some batches of iMac G5 and eMacs, have also suffered ‘capacitor plague’ when counterfeits have somehow entered the assembly plant. Since first reports in 1999, successive waves have cost major manufacturers hundreds of millions of dollars to rectify.

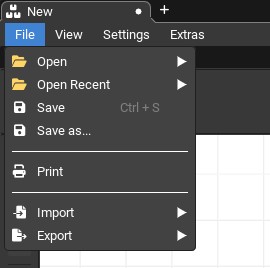

An ABIT VP6 motherboard with a blown capacitor alongside others that are bulging or leaking (2007). Image by Ethanbrodsky, via Wikimedia Commons.

An ABIT VP6 motherboard with a blown capacitor alongside others that are bulging or leaking (2007). Image by Ethanbrodsky, via Wikimedia Commons.This PC motherboard from ABIT has one blown capacitor obvious just to the left of centre, among others that are starting to bulge and leak.

Fortunately, Apple’s products were among the least affected, and since 2007 very few problems have been reported, although failed capacitors and leaky batteries remain problems in any computer over 15 years of age.

Lead-free solder 2006-2017

No sooner was capacitor plague dying out than a new wave of failures was reported, mainly affecting better graphics cards, including some installed in various models of Mac. The most prominent was probably that in 2011 MacBook Pro models, but several other MacBook Pros, iMacs, and others were affected. My own iMac 27″ Mid 2011 (iMac12,2) suffered failure in its Radeon HS 6970M graphics card, and was one of several models whose warranties were extended because of this issue.

Apple wasn’t the only computer manufacturer to have such problems. Various models, mainly laptops, from PC manufacturers including Asus, Lenovo, and HP, had similar high failure rates in their graphics cards. Although some occurred as a result of GPU failure, the single common cause accounting for many was most probably the use of lead-free solder.

High-performance graphics cards run hot, because they do a lot in a small volume, particularly in compact systems such as laptops and all-in-one desktop models. Laptops have very high thermal stresses, because they’re often left cold for long periods, then run and become hot enough to warm bare thighs. Components, especially the GPU, may thus cycle between cold and hot several times a day.

On 1 July 2006, the EU banned the use of significant quantities of lead in most consumer electronics products, including computers and their accessories. Although this had the beneficial side-effect of reducing occupational exposure to lead fumes in those manufacturing and repairing electronic circuit boards, the drive for this came instead from growing concerns over lead in electronic waste.

The most immediate impact of that ban was the withdrawal from sale of Apple’s iSight camera at the end of that year, as that couldn’t be made using lead-free solder. Since then, substitute lead-free solders have become universally adopted in consumer electronics manufacture, but some non-consumer products continue to use traditional lead-based solders. This is because, despite sustained efforts to develop lead-free solders that perform as well, in practice products manufactured using them are more prone to failure, and have shorter working lives. Over the last decade, improved manufacturing techniques have reduced the chances of early failure, but now I’m happier using Apple silicon chips in any case.

Butterfly keyboards 2015-2019

In 2015, Apple released new MacBooks that incorporated a keyboard using a novel action, described as butterfly. These enabled their integrated keyboards to be thinner, and because this mechanism distributed finger pressure more evenly, Apple claimed the keys were more stable in use, and required less movement.

Although some preferred these butterfly keyboards, and had no problems in use, others started to report early failure, with keys getting stuck, repeating, or failing completely. These have been attributed to the accumulation of debris in the greater space within the keys. Attempts were made to tweak their design to eliminate these problems over the following four years, but ultimately Apple had to return to the proven scissor mechanism, which it did from 2019. As a result Apple had to operate its largest repair programme ever.

Apple Service Programmes

Although at times Apple might appear intransigent when problems occur with its products, its record ranks among the best of all computer manufacturers. There are currently two active service programmes, for 15-inch MacBook Pro batteries dating back to 2019, and more recently for a small number of M2 Mac minis. I repeatedly hear of those whose Macs have been replaced or repaired at no cost in order to satisfy customers, even though warranty, AppleCare or extended service programmes have expired. It’s one of Apple’s distinguishing features.

.png)