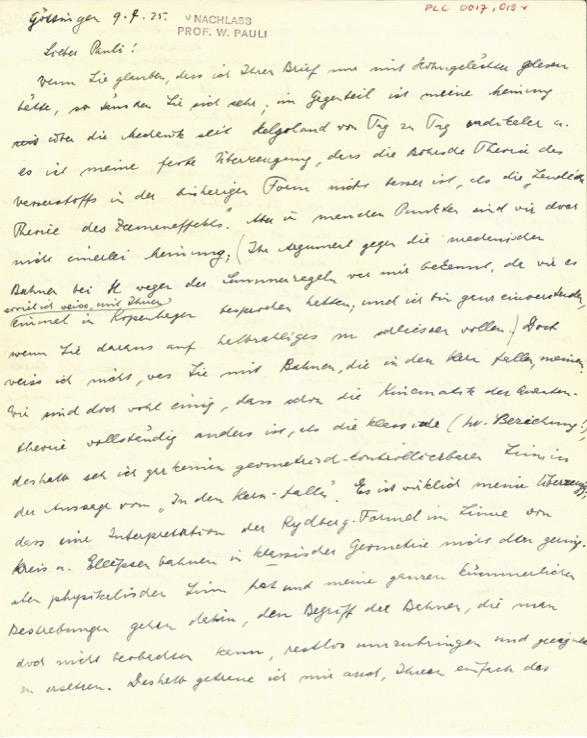

On 9 July 1925, in a letter to Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg revealed his new ideas, which were to revolutionise physics

Just 100 years ago, on 9 July 1925, Werner Heisenberg wrote a letter to his friend, colleague and fiercest critic, Wolfgang Pauli. A few weeks earlier, Heisenberg had returned from the North Sea outpost of Helgoland, where he had laid the foundations of modern quantum mechanics and changed our understanding of the atomic world. The letter, preserved in the Wolfgang Pauli Archive at CERN, reveals Heisenberg’s efforts to liberate physics from the semi-classical picture of atoms as planetary systems, with electrons in orbit around the nucleus.

“All of my pitiful efforts are directed at completely killing off the concept of orbits – which, after all, cannot be observed – and replacing it with something more suitable,” he explains in his letter to Pauli.

By sweeping away the old interpretation, Heisenberg could focus on building a more coherent model, based purely on what the experiments were observing. Attached to the letter was the draft of Heisenberg’s famous Umdeutung paper, which was received for publication a few weeks later, and which is often considered as the birth certificate of modern quantum theory. In the following months, Max Born, Pascual Jordan and Wolfgang Pauli himself helped turn Heisenberg’s work into matrix mechanics, the first mature formulation of quantum theory.

Today, those early reflections underlie the most precise framework in the history of science: the Standard Model of particle physics. Experiments at CERN keep pushing it to extreme regimes, and time and again, it proves astonishingly accurate.

To celebrate 100 years of quantum mechanics, the CERN Courier looks back at the impact of this theory and examines how it keeps delivering new puzzles, experimental ideas and technologies. For instance, quantum sensors may soon extend their reach from low- to high-energy applications, while quantum simulations could help overcome the limits of classical computing in describing extreme environments and complex systems.

Theoretical and philosophical considerations, too, are far from exhausted. Despite its empirical power, there is still no consensus about quantum theory’s true meaning. What guides the emergence of our classical world? Is the wavefunction a real entity, a representation of the observer’s knowledge or an artifact we should abandon altogether? Should we think of measurement apparatus and observers as quantum objects?

Heisenberg himself was cautious yet hopeful, writing to Pauli: “Perhaps people who can do more, will be able to make sense of it.” A century on, physicists are still working to fulfil that dream. Whatever the last word may be, one thing is certain: the conversation sparked on Helgoland is far from over.

- Read the new issue of the CERN Courier magazine and its special report on 100 years of quantum physics.

- Explore the Wolfgang Pauli Archive.

Lieber Pauli...

Read the translation of the letter sent by Werner Heisenberg to Wolfgang Pauli on 9 July 1925. The original letter is preserved in CERN’s Wolfgang Pauli Archive.

(Copyright: Heisenberg Society)

(Copyright: Heisenberg Society)

Dear Pauli,

If you believe that I read your letter laughing mockingly, then you are gravely mistaken; quite the contrary – since Helgoland, my views on mechanics have become more radical with each passing day, and it is my firm conviction that Bohr’s theory of the hydrogen atom, in its present form, is no better than Landé’s theory of the Zeeman effect.

However, on certain points we do not agree. (Your argument against mechanical orbits in H on account of the sum rules was already known to me; we discussed it with you once in Copenhagen, if I am not mistaken. And I fully agree, should you wish to deduce from it that m must take half-integer values.)

But I do not know what you mean by orbits “falling into the nucleus.” Surely we are agreed that even the kinematics of quantum theory is wholly different from that of classical mechanics (the hν relation!). I therefore see no geometrically intelligible or controllable meaning in the notion of “falling into the nucleus.” It is, in fact, my sincere conviction that any interpretation of the Rydberg formula in terms of circular or elliptical orbits within classical geometry possesses not the slightest physical significance, and my entire pitiful effort is directed at exterminating the concept of orbits – after all, they cannot be observed – and replacing them with something more appropriate.

For this reason, I take the liberty of simply sending you the manuscript of my work. I believe that at least the critical, that is to say, the negative portion contains real physics. I do feel terribly guilty, however, for having to ask you to return the manuscript within two or three days, as I should like either to complete it during the last days of my stay here – or to burn it.

As for my own opinion of this scribbling, with which I am not at all satisfied: I am firmly persuaded of the value of the negative and critical part, but I regard the positive part as rather formal and poor. Still, perhaps those more capable than I may yet make something sensible of it. So I would ask that you concentrate primarily on the introduction as you read.

Regarding the final point of your letter: I did not mean to say that the intensity of the 2536 line is 1/30 – that value has, after all, been measured. What I meant was rather this: the 2p² → 2s transition, which is almost solely responsible for the splitting of the 2p² level, when one attempts to interpret the Hanle splitting, appears to amount to roughly 1/30, which to my mind does not seem in agreement with the spectrum.

Now then, I beg you once more for sharp criticism and the swift return of the paper!

Many greetings to the entire Institute!

W. Heisenberg

.png)