I’ve spent the last year working on local-first apps, most recently with Muni Town. For me, ‘local-first’ isn’t just a technical architecture — it’s a political and social stance. It’s about shifting control: from remote servers and top-down central authorities deciding how data, workflows, and communities operate, to individuals and communities reclaiming that control and gaining autonomy. Seen this way, privacy and consent aren’t add-ons — they’re foundational, just as critical as sync or data locality.

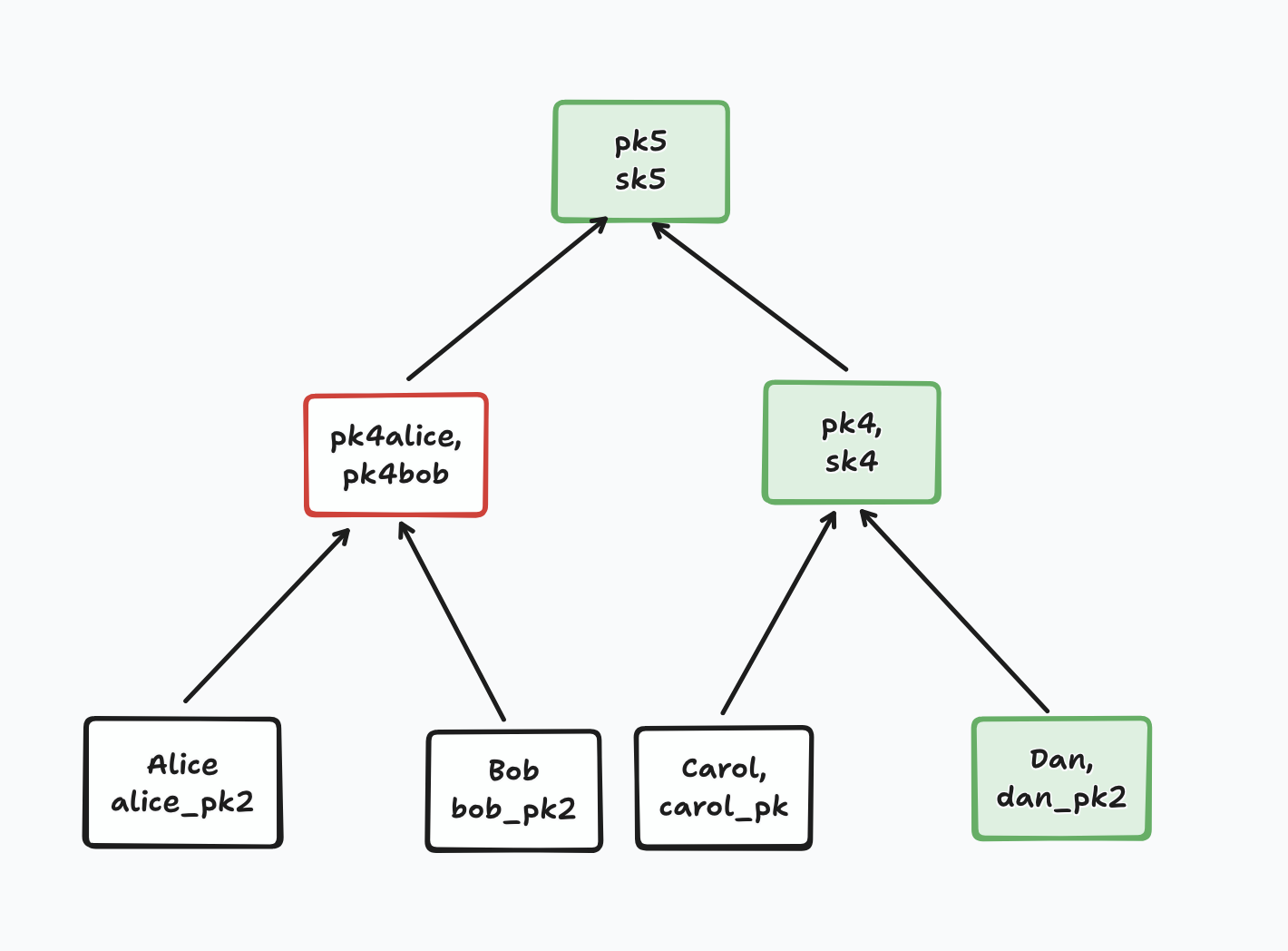

Ink & Switch’s Keyhive project is a capabilities-based system for CRDT authorisation and sync that opens up real possibilities for privacy-preserving local-first apps. Libraries like Automerge, Yjs, and Loro have already made it viable to build real-time collaborative apps without relying on a centralised authority to manage consistency. Yet in practice, we still lean on central servers for sync — with all the privacy implications that entails.

Encrypting CRDT operations end-to-end sounds like an easy fix, but in practice it’s tricky. Most CRDT implementations rely on batching many fine-grained operations — often keystrokes — into compressed runs to reduce metadata overhead. Encrypting every individual operation separately breaks that optimisation, making CRDTs too inefficient to use. On top of that, group collaboration introduces the full complexity of Secure group messaging, where typical encryption schemes (like Signal’s) don’t translate cleanly due to CRDTs’ inherent concurrency and branching structure.

And even then, encryption only solves the read side of the problem. Keyhive goes further, enabling distributed capability-based authorisation. It models access control roles — read, write, admin — through chains of signed delegations. It also introduces Sedimentree, a mechanism for probabilistically compressing and encrypting CRDT updates based on DAG depth (as a proxy for concurrent update likelihood).

At Muni Town, we’re planning to use Keyhive for access control in Roomy, so I’ve been digging deep into how it works. The part I’m most interested in is BeeKEM, their proposed Key Encapsulation Mechanism. It formalises how keys are exchanged and managed within this decentralised, capability-based system. I wrote a research report for uni last year on almost exactly this topic, which made me especially keen to put that knowledge into use here. While the Keyhive team haven’t published a paper as yet, there is a Lab Notes article, various bits of documentation, and a Rust implementation. To try to learn-by-teaching, I’ll be doing my best in this post to explain how BeeKEM works.

Secure messaging basics

Since Signal protocol (aka the Double Ratchet algorithm) set a new standard for end-to-end encrypted messaging, there has been a lot of academic focus on abstracting and formalising the key components and pushing them further. Signal protocol is fundamentally designed for two-party secure messaging (2SM), meaning that every message sent using the protocol is encrypted with a key that is shared only with the recipient, which (through very clever use of Diffie-Hellman key exchange and keyed hash functions) they both independently derived for that message. It’s possible to use the Signal protocol for group messaging by applying the two-party protocol for every pair of group members. The catch is that you have to re-encrypt your messages for every group member, and everyone has to derive keys for everyone else, so in general for n group members there is n^2 complexity, which gets infeasible fast.

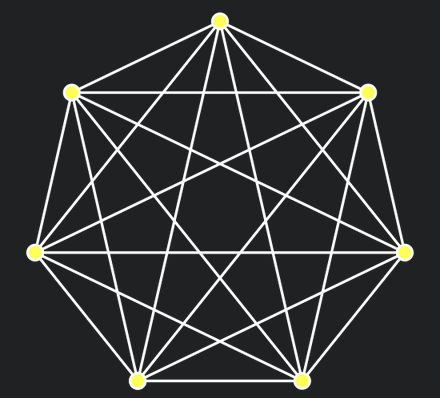

A complete graph, representing the number of pairwise protocol instantiations for a Signal group of 7 people. Source

Academics and industry people have since dedicated a lot of attention to finding a solid way to achieve efficient secure group messaging (SGM). A key requirement for this was to make it possible for encrypted message broadcast - that is, for each group message we send, we can broadcast one encrypted message for the entire group to decrypt - without losing the key security properties of Signal protocol. Thus far the most widely adopted approach has been Sender Keys, used by WhatsApp and Signal. Essentially every group member sends every other group member, via pairwise 2SM, a symmetric key that it will use to encrypt messages. To receive messages, users keep a list of these keys, one for each other member. These keys can then be ‘ratcheted’ with a keyed hash function to derive new keys for each message - once the old keys are deleted, this provides Forward secrecy, meaning that old encrypted messages are protected from a later key compromise. This simple approach makes application-level stuff (sending messages) fairly efficient - it’s just the group-level (key management) stuff, such as adding and removing members, which retains the performance limitations of pairwise groups.

TreeKEM

Improving further on this, the Messaging Layer Security (MLS) standard has been published, representing a community convergence on a solid approach to secure group messaging. MLS significantly improves on the key management part through the TreeKEM (sub-)protocol. In TreeKEM, rather than having to negotiate one key for each sender, the group members cooperate to calculate a single key that is shared between everyone for the duration of an ‘epoch’ - a given state of the group. Not only that, but the process of cooperation is significantly more efficient. Here’s how it works:

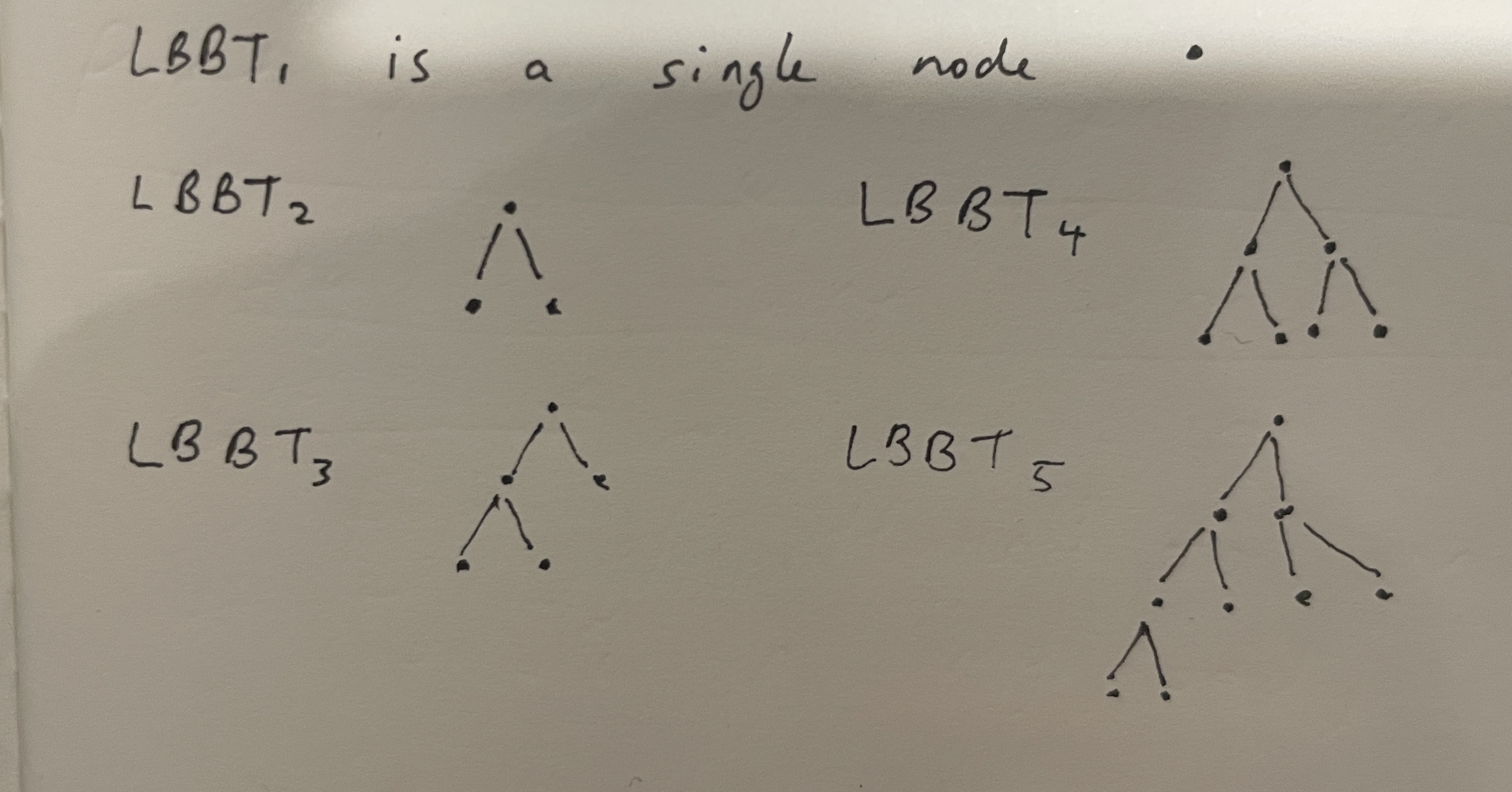

When new members join a group, they are assigned a position among the leaves of what’s called a left-balanced binary tree (LBBT). These look like this:

Edit: from looking at the code, trees in BeeKEM (and possibly TreeKEM) don’t actually grow in this way! They start at the left and keep adding to the right, up or down as necessary. I’ll do a new diagram if I get a moment!

Once you know your position in the tree, you can work out who your sibling is - the node that shares a parent with you. Next we can imagine that every node may correspond to a public and private key pair.

Something that was helpful for me in understanding this idea of the members being in a tree was to clarify that there isn’t actually any single node that contains all of the data in this tree. We can know all the public keys for every node, but in general, you only know the secret keys for yourself and any nodes above you, up to the root. This is fine, because all we actually care about in the end is working out the secret key for the root. We do that through Diffie-Hellman (DH) key exchange between the sibling of the nodes we know secret keys for, starting with our own node.

This stuff is also explained in Ink & Switch’s Lab Notes on BeeKEM

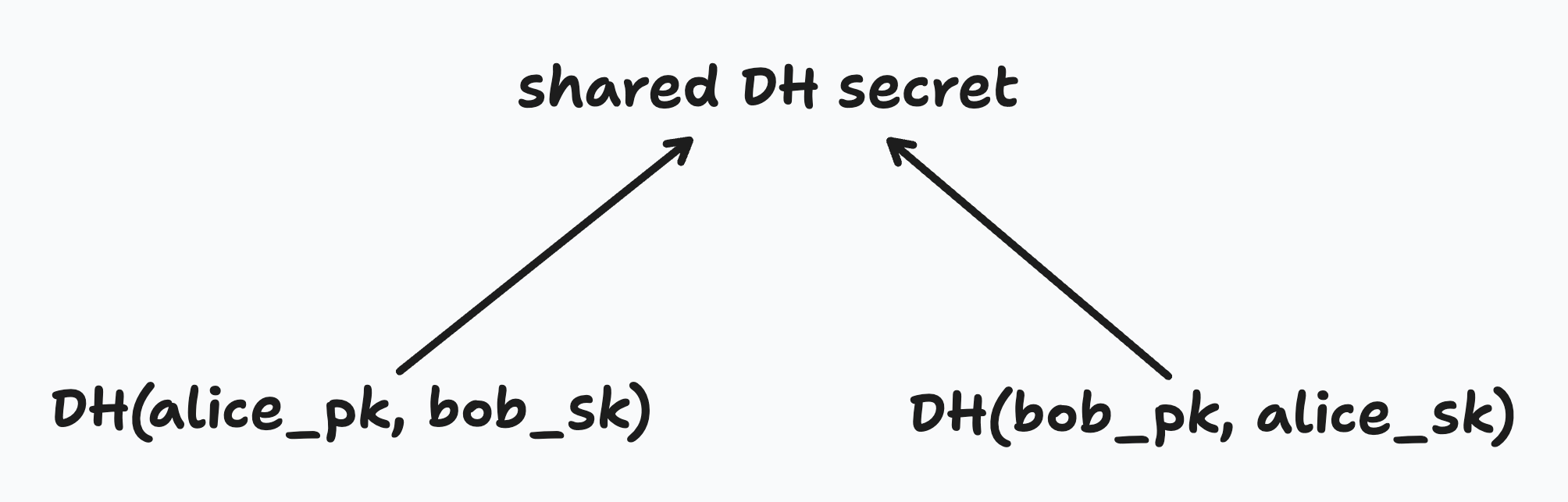

So if I’ve generated a key pair, and I know my sibling’s public key, I can just use discrete logarithm magic to ‘combine’ them together and end up with the same secret that my sibling got from combining their secret with my public key.

Once I have calculated the secret for the parent of me and my sibling, we can work out our parent’s parent using the public key of our parent’s sibling - on and on up to the root.

On first look I had assumed the DH shared secret we derived for the parent was the secret part of the key pair. Actually, the member performing an update will generate new secrets for the whole path up to and including the root by feeding the random new secret at their leaf node into a KDF, and then generate a public key corresponding to each secret. Each secret is then encrypted using the shared secret at each node.

Now we understand the basic structure, we can look at three main operations. The first is updating the group secret. Basically any group member can at any time ‘blank’ (delete) all the keys on its path up to the root and generate new ones as per above, and they just need to broadcast the new public keys at each of the nodes.

The second is removing a member, which is essentially done by updating the group key and not telling the removed member the new public keys. We also reorganise the tree here so it’s still a left-balanced binary tree.

Thirdly, any group member can add a member, by creating a new leaf in the LBBT and generating key pairs for the new path from the new member up to the root. It sends the new member an encrypted ‘welcome message’ including all the public keys in the tree and the full key pairs for the entire path. Once the new member is added, they should probably perform an update to rotate all their key material.

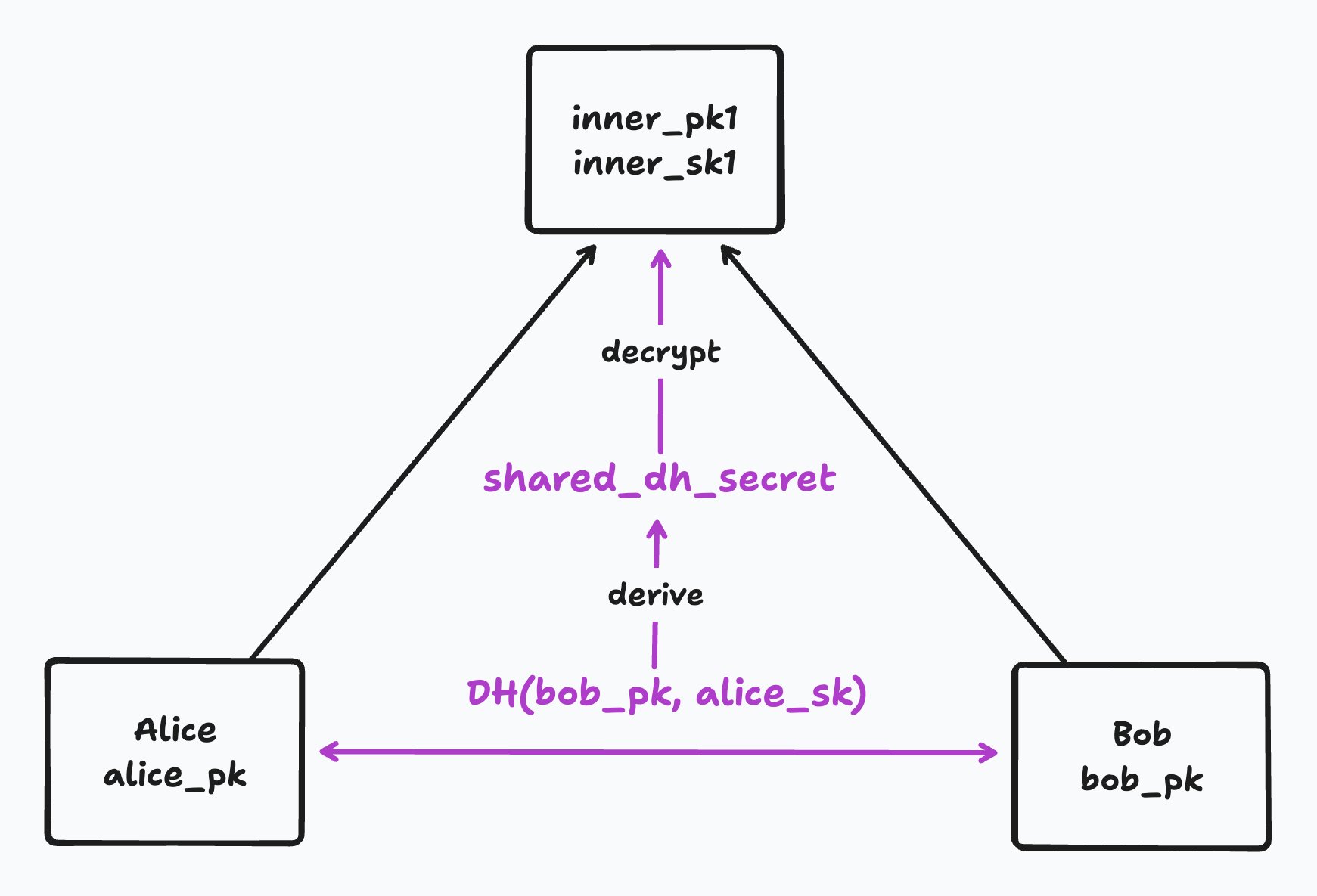

How is the encrypted welcome message sent?

The new member hasn’t been added to the group yet, so the welcome message can’t be sent using the group secret - it needs to be out of band of the group. This could be done in various ways - a Signal message, for instance - but in MLS it is achieved with Public Key Infrastructure that can deliver a fresh public key for any user to the adding member.

All together these are the three essential operations of TreeKEM.

TreeKEM and Strong Consistency

CRDTs provide Strong Eventual Consistency, which is a kind of non-trivial eventual consistency. The original paper motivates this definition:

Several [Eventual Consistency] systems will execute an update immediately, only to discover later that it conflicts with another, and to roll back to resolve this conflict. This constitutes a waste of resources, and in general requires a consensus to ensure that all replicas arbitrate conflicts in the same way. Shapiro et al, 389

Ok, to be fair, that doesn’t sound that trivial, but the point is that it’s not the ideal approach if you want your app to handle network partitions seamlessly. Strong Eventual Consistency means that we can actually apply updates in different orders and still arrive at the same state. In other words, we can model updates as a partial order, rather than a total order.

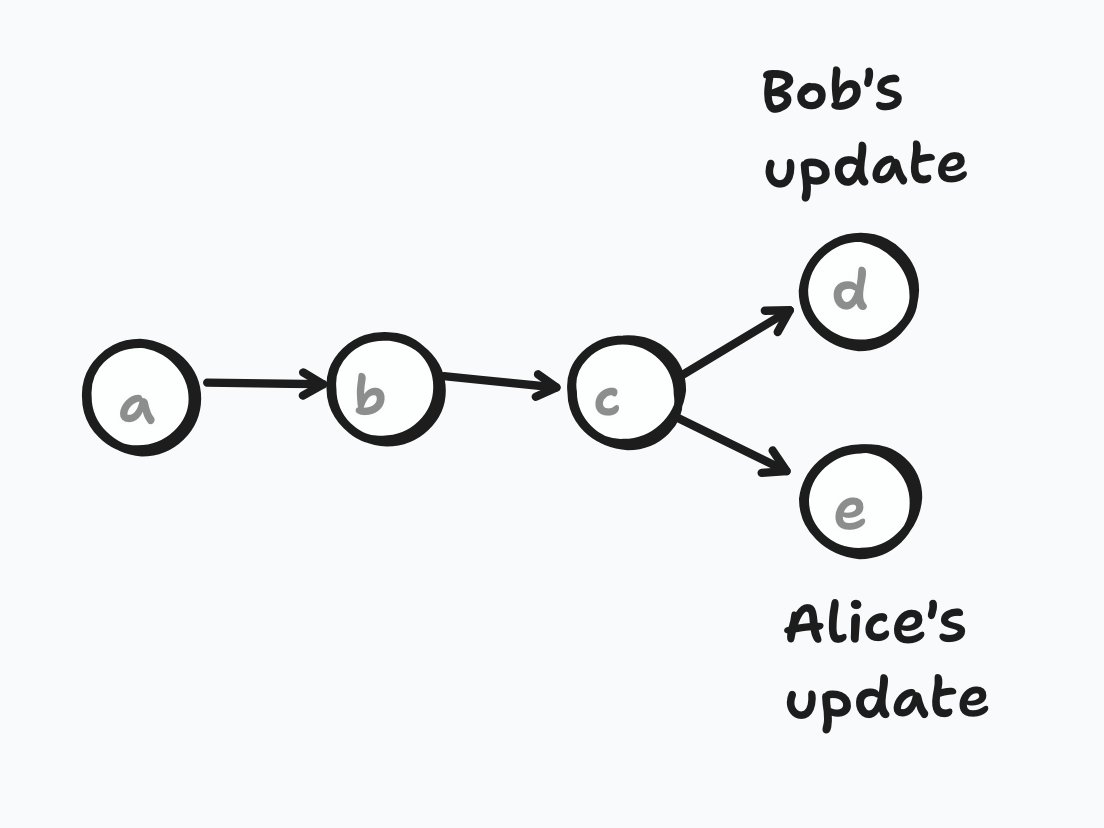

TreeKEM in general assumes a total order of state updates, which is less tolerant of network partitions. Every member is responsible for keeping their local copy of the tree up to date, and make updates (such as adding a member) directly to it, but if it turns out someone else added another member concurrently, the server could easily come back and say Sorry, that position in the tree is taken! You need to roll back and try again.

Note: MLS, for its part, does have some tricks for handling and merging concurrent updates, but ultimately it does all need to resolve in this linear way.

BeeKEM vs TreeKEM

BeeKEM has a different way of handling the situation of multiple members being added to the same tree index concurrently. Rather than having a central authority arbitrate whether an operation was successful or not, the validity of each operation will simply be considered within its causal context - which is to say, whether it was a valid operation for the previous tree state that the updater knew about.

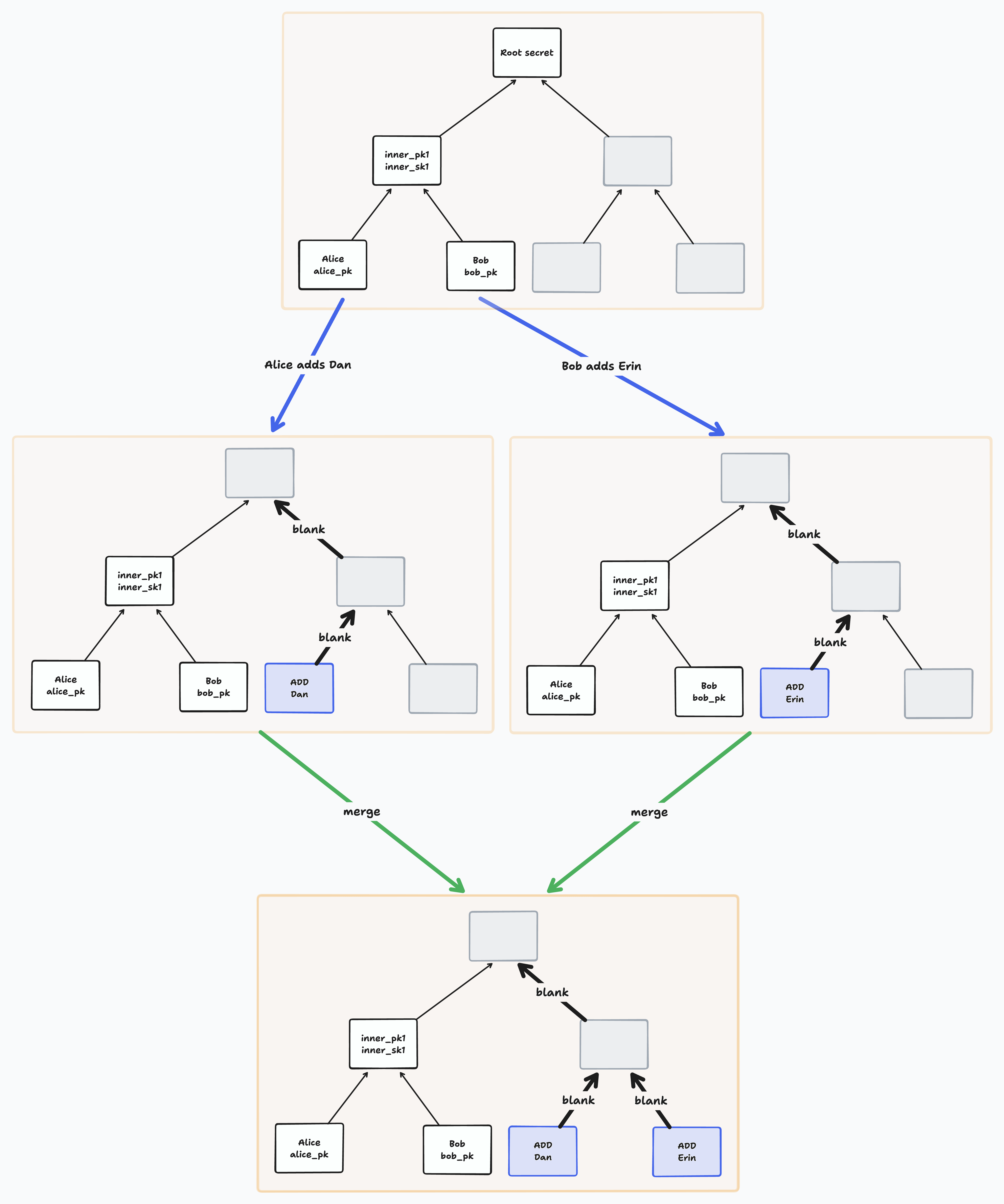

Notice that if two members add a member concurrently to the same tree, they will add them to the same leaf. BeeKEM resolves such conflicts on merge by sorting all concurrently added leaves and blanking their paths. [Group Key Agreement with BeeKEM

You can imagine that Alice and Bob were both offline when they added Dan and Erin to the group, and then proceeded to send some application messages with the new group key each of them generated. Once they come back online, will anyone else be able to decrypt those messages they wrote?

For TreeKEM, this wouldn’t work - you might be able to generate a group key and encrypt something with it, but once you come back online, the server will learn of your commit to the group state and reject at least one of them, so either Alice or Bob will need to try again to add Dan and Erin, and re-encrypt the messages they had sent. Everyone in the group depends on a total order of group state operations to know what’s valid.

In BeeKEM, we can imagine that Alice, having added Dan offline, will be able to send messages encrypted in such a way that Dan will later be able to access them, and vice versa with Bob and Erin. How does this work? Let’s look at the update key process in more detail.

PCS Updates in BeeKEM

Just as a reminder, the reason we update the group secret is to provide ‘post-compromise security’, or PCS. A simple scenario would be that we just found out Bob is a federal infiltrator and proceed to kick him from the group. It’s obviously important that Bob doesn’t learn the new group key so we can encrypt in peace, and this is done more or less the same way as in TreeKEM described above.

We could also imagine a situation where Bob is an honest group member who has been arrested and his phone has had its secrets mechanically exfiltrated by the cops (we will presume for simplicity that no spyware has been installed). In this situation, Bob needs to be able to update to a new random key pair so the outsider access is no longer possible. Unfortunately Bob is offline, but he wants the key pair updated as soon as he comes back online.

He generates a random new key pair for his node then ratchets a KDF (in BeeKEM, it’s a keyed Blake3 hash) to generate new secrets up the path to the root. He derives public keys from these secrets, and then needs to encrypt the secrets at each node on the path using the DH secret shared between that node’s two children. Great, this is all more or less the same as in TreeKEM.

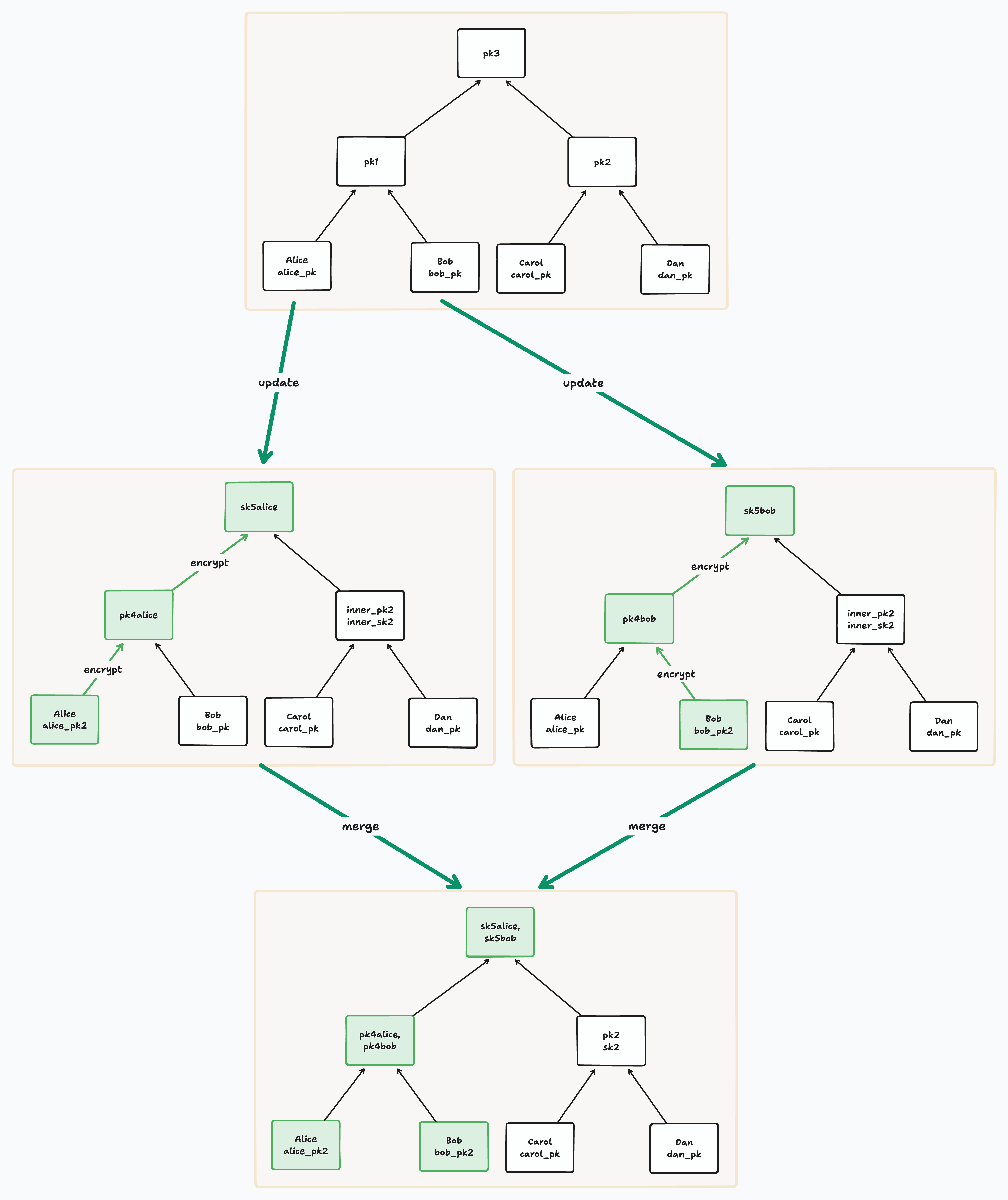

But the fact that this is happening offline means that Alice (e.g.) might have done an update concurrently - either while adding or removing a member, or just for general PCS hygiene. We don’t want to throw away any concurrent updates, and we don’t have to, if we can find a way to get back to consistency.

As soon as any group member learns of both Bob’s and Alice’s updates, they will understand that some nodes in the graph are conflicted - meaning they have multiple keys assigned to them. Everyone needs to hold on to these multiple keys, until a new update overwrites those nodes.

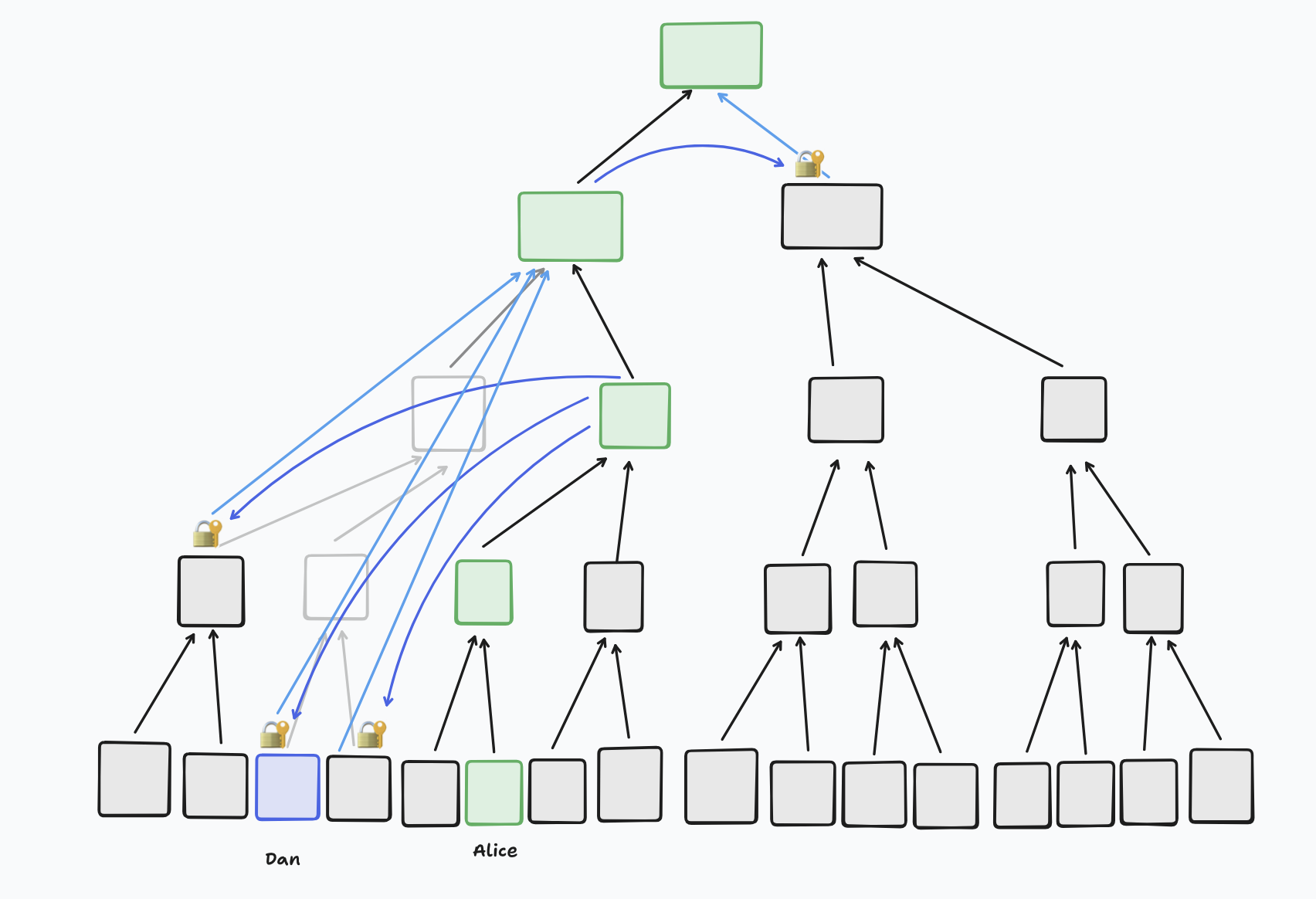

Here’s a diagram from the Ink and Switch article showing what happens when Alice and Bob make concurrent updates:

You can see that the root has multiple keys, and is therefore conflicted, and so is Alice and Bob’s shared parent.

When you make an update, you update only the nodes on your path to the root - so in this situation, if Carol makes an update, she will get rid of the conflict at the root node, but not the conflict at Alice and Bob’s shared parent. But if Alice makes a (non-concurrent) update, she will resolve all the conflicted nodes. What is clever about BeeKEM is that you can still decrypt messages even if you are aware of conflicted nodes on your path, including the root. How does that work?

Let’s visualise Alice and Bob’s updates to the state as a DAG, where every group state explicitly depends on one or multiple previous states:

As a reminder, when you make an update, you send everyone the new ECDH public keys for the nodes on your path. So once Bob came back online, he would have sent these out. If everyone else already had Alice’s update, then they would all now know that the nodes on their paths that overlap are now in conflict - above, that would be the root and its left child.

When Bob came back online, he will have also sent out the application messages he encrypted using his new key. Even though they already know of a different (better?) group key, they have everything they need to work out the group key that Bob encrypted to. Alice, learning of Bob’s new leaf public key, can DH it with her old secret key from the old state to derive the shared DH secret Bob will have used to encrypt the secret at their shared parent, and she can just ratchet the group key from that.

Some thoughts on Forward Secrecy

FS is intentionally out of scope for Keyhive, effectively prevented by the ‘causal encryption’ mechanism. I am interested in FS in general and the BeeKEM Lab Notes do mention that as a KEM it offers forward secrecy. As far as I can tell, this is possibly true of the KEM itself in some technical sense, but not really true at the level of application messages.As I’m thinking through how members deal with concurrent updates, it does seem like there is a bit of a tradeoff here where, if you want to be able to decrypt past application messages after a concurrent update you weren’t aware of, you do need to hold onto node secrets on your path. Holding onto past secrets wouldn’t be good if device compromise was part of your threat model. But since for CRDTs you do actually need access to past updates, maybe there is no point deleting keys at all.

In his thesis describing ‘Causal TreeKEM’, Matthew Weidner describes that protocol as offering forward secrecy (“Causal TreeKEM supports arbitrary concurrent state changes while achieving strong and intuitive forward secrecy and post-compromise security guarantees.”, 31), but later states: Users cannot delete their old Causal TreeKEM keys until they are sure that they have received all concurrent state change messages, which may take an arbitrary amount of time. These old keys can be used, together with a past compromise, to read old messages. Even without a past compromise, we cannot achieve forward secrecy at the granularity of individual messages by using deterministic key ratcheting and deleting message decryption keys, as described in Section 3.3. This is because a malicious user may send multiple messages with the same number, hence the same encryption key. A lack of forward secrecy may be acceptable for secure collaboration, since users will likely store a full plaintext history anyway.

In Key Agreement for Decentralized Secure Group Messaging with Strong Security Guarantees, the authors (including Weidner) state that Causal TreeKEM “modifies TreeKEM to require only causally ordered message delivery (see Section 5.1), at the cost of even weaker forward secrecy”.

Forward secrecy is interesting, like it sounds really important but when I think about what the threat model is, it seems like a rare situation where an attacker would gain access to only the current key but not many if not all past keys/content - like probably directly compromising your device is most likely right? In which case, what are you trying to achieve?

Carol and Dan will DH the secret key of their parent, the root’s right child, with the public key for the left child, to get a shared secret for the root - which can then be used to decrypt the actual root secret that Bob got by ratcheting. (Side note, but this is another cool thing about the tree structure I recently, that a subset of members can get a little speedup by ratcheting proportional to how low in the tree their intersection with the encrypter’s path is).

Resolving conflicts

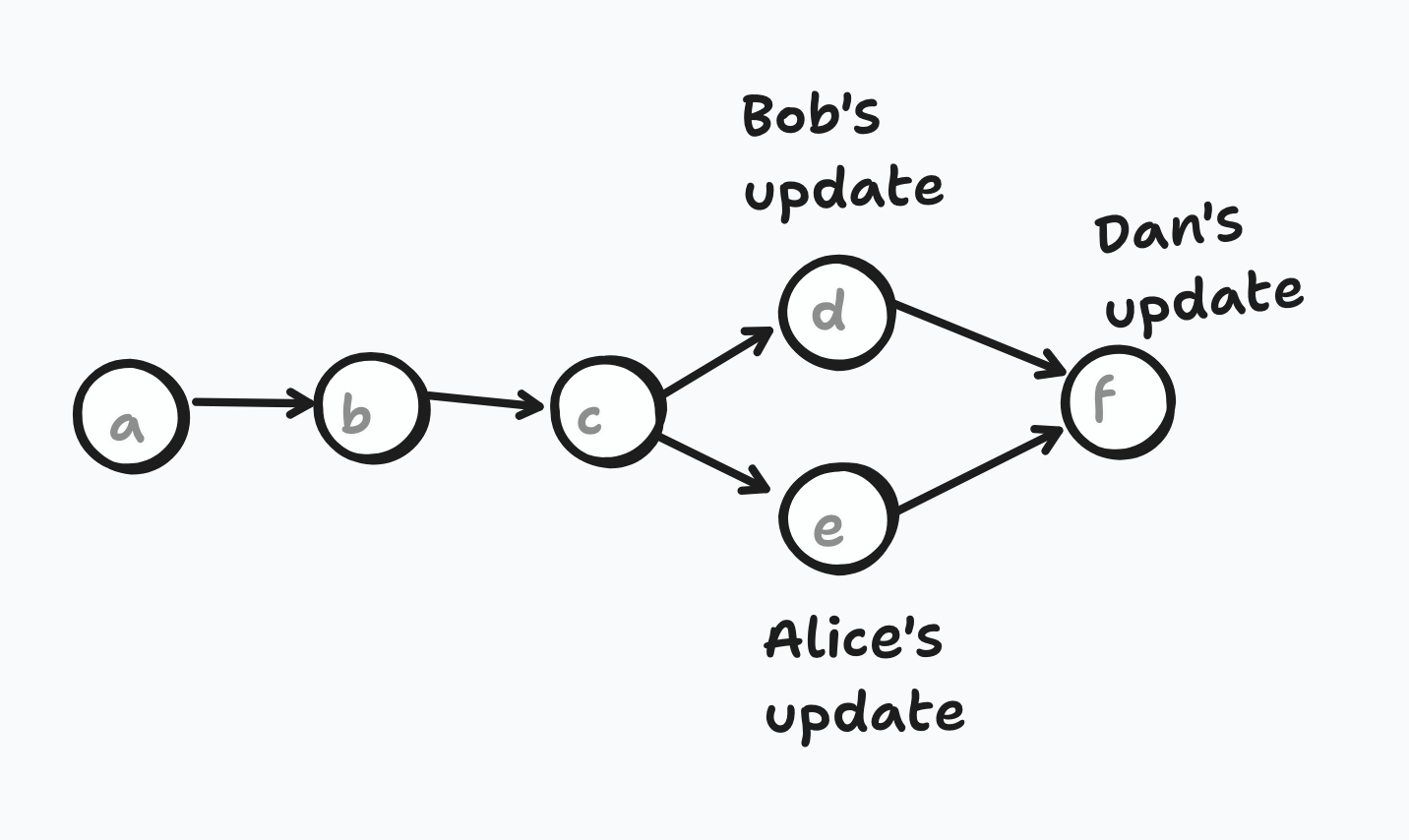

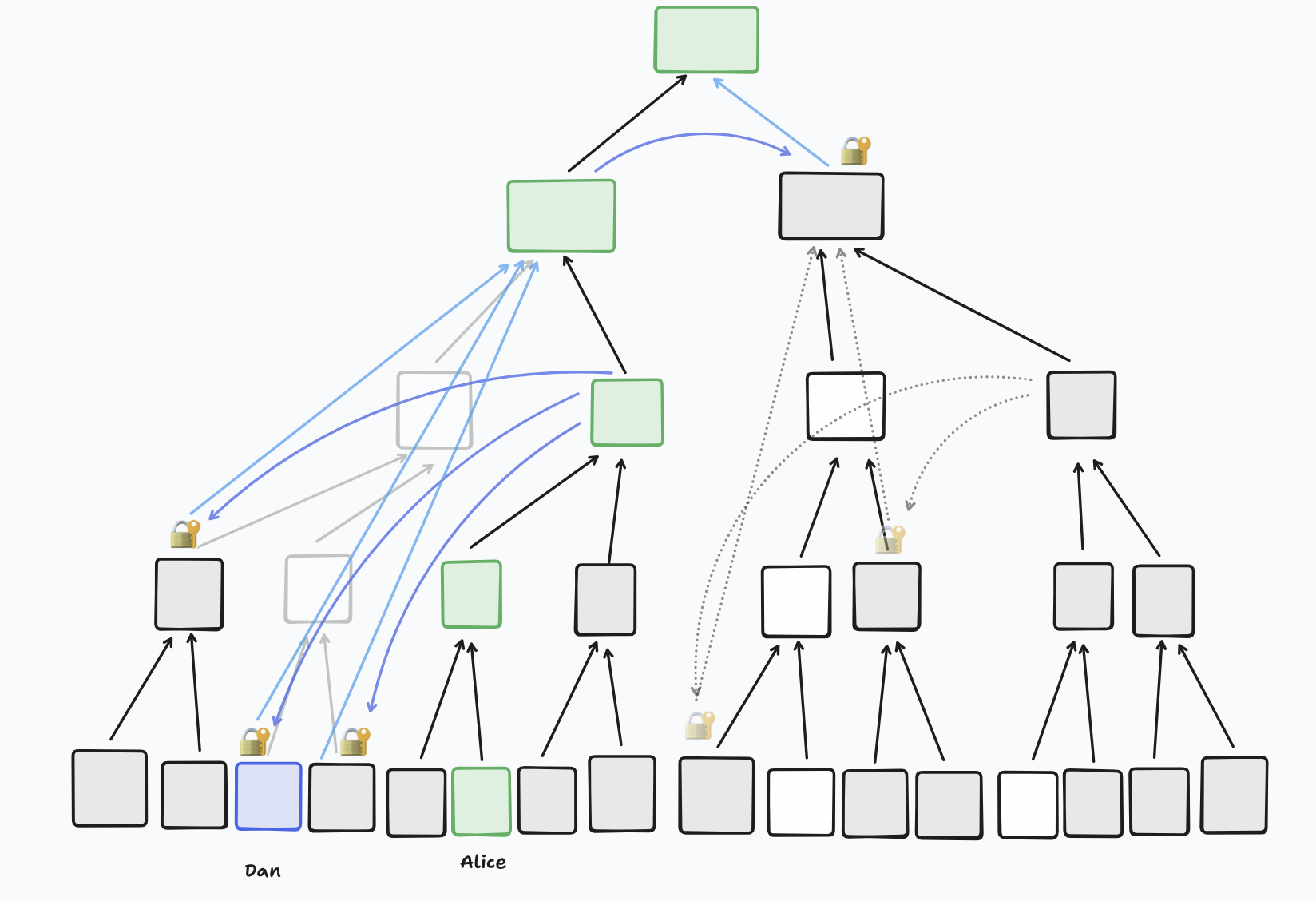

The above approach is great for when you want to decrypt updates that are, by nature of being made unaware of other concurrent updates, inherently outdated. But it’s not secure to encrypt new data once you are aware of any conflicts on your path. You need to do your own update first, which resolves the conflicts at least to the extent that they affect the group key for you. So if, in the above situation, Dan goes on to perform an update:

Dan will only replace the keys on his path, which means the root key conflict will be resolved, but the conflict at Alice and Bob’s parent won’t be resolved until Alice or Bob perform another update.

The only problem here is that generally, Dan would encrypt the secret key at the root with the DH shared secret of the public key at the root’s left child, and the secret key at the root’s right child (which he just generated). In this case, because the left child is conflicted, there isn’t a clear key to encrypt to, so instead he just considers the left child to be blank and encrypts separately to each node in its resolution. In BeeKEM, the resolution of a node means its highest descendants that are non-blank and non-conflicted, or in other words, where we have exactly one public key for it.

What if an add is concurrent?

Earlier I described a situation where Alice, offline, adds Dan, concurrently to Bob, also offline, adding Erin. Let’s step through what would exactly happen.

- Alice calls add_member on her local Keyhive Document with Dan’s ID and a pre-allocated public key he provided earlier. This internally calls add on the CGKA struct, which internally calls BeeKEM’s push_leaf, potentially growing the tree in doing so.

- Alice blanks all the nodes on Dan’s path to the root

- Alice updates all the keys on her own path and prepares a message with:

- The public keys at each node

- The secret key at each node, encrypted with the ECDH shared secret derived from the secret of the child on her path and the public key(s) of the resolution of its sibling. Note that, because Dan’s entire path is blanked, the resolution of at least one of the nodes on Alice’s path must include Dan’s leaf node - so she will encrypt the secret key for that node for him personally. The number of encryptions she needs to do depends on how many nodes in the tree are blank or conflicted.

Here’s a situation where, because Dan’s path is blanked, the secret key for the third node up Alice’s path is used to DH with the PKs of the resolution of its sibling - including Dan’s leaf. The darker blue arrows indicate that the recipient’s PK has been encrypted for, and the lighter blue arrows indicate that the encrypted content is the secret key of the node the arrows are pointing to - in this case, the root’s left child.

A little variation showing that it doesn’t matter if nodes below the resolution (in this case, the right child of the root) are blank, because all nodes below that node should already know its secret key, so can decrypt the new material - in this case, the root secret.

- Alice may send application messages, intended for Dan and the rest of the group she knows about

- Alice’s messages stay on her device because she is offline!

- Bob does the same as Alice, but instead adding Erin to the same position Alice added Dan to - they both would have had the same next_leaf_idx set

- When they both come online they send out their respective messages and key updates, both referencing the same hash for the previous tree state as a dependency

- Everyone else, upon receiving the updates and determining that the updates depend on the same hash and are therefore concurrent, merges the updates into their own tree in a commutative way - i.e. the order the updates are applied makes no difference

- The newly added Dan and Erin will be sorted by ID, with one of them being moved to a new index

- The nodes to which multiple keys were written become conflicted

- Dan will be able to reconstruct the state sent by Alice, and Erin will be able to reconstruct the state sent by Bob, and each can only decrypt the messages that were sent by their respective adders.

- To complete the adding process, both Dan and Erin need to perform key updates, and then someone else needs to update, to make them both aware of each other.

Newly added members, at least for TreeKEM I think, should perform a PCS key update as soon as they can after they are added, so they have a complete path to the root and fresh keys. But if e.g. Dan only know about Alice’s update that added him, he may not know that everyone else has realised there were concurrent adds and has subsequently sorted their tree, meaning that his index in the tree actually should be somewhere else. I guess if Erin was added concurrently, and her position stayed the same, her key update would be concurrent to Dan’s. Neither of them know about the other so neither of their updates, if I’m understanding right, get sent to each other. From everyone else’s perspective, their entirely overlapping paths (including the leaf) are just in conflict until someone else does an update and sorts them?

Based on my current understanding I can also only speculate what happens when two members concurrently remove each other, which is essentially that they both get removed - but again, I’d like to get clarification on this. My final wondering about BeeKEM is how it handles multiple compromises. Weidner et al. write of Causal TreeKEM that “after multiple compromises, all compromised group members must send PCS updates in sequence” (s3). The details of how this potential vulnerability works sit slightly beyond my current understanding but it’s something I’m curious about and would like to keep digging into.

In TreeKEM, the requirement of strong consistency for the group state means that operations on the group state need to be totally ordered, and group members effectively all progress together from one ‘epoch’ to another. But while all members do need to regularly update the group key to ensure post-compromise security, BeeKEM gives us stronger capabilities for recovering from conflicting offline updates and network splits, by explicitly modelling the group state as potentially existing in multiple epochs simultaneously.

The central way this happens is that, when members receive conflicting updates, they can simply hold on to all of the keys they received for each node, thus marking them as ‘conflicted’. This means we can continue to decrypt and read application messages stemming from the conflicting epochs. Then when we want to progress the group state with another update, we basically just consider the conflicted nodes to be blank.

I’m excited for the authors to publish their paper where BeeKEM’s affordances and limitations can be expressed more formally, and to dig into making apps that take advantage of and support the Keyhive project more generally. Thanks for reading!

.png)