The latest Nielsen ratings report finally includes streaming data—but only some, so it’s an incomplete picture, especially for anime. While not always taken at face value, these are generally considered the best numbers available, guiding both public perception and western media decision-makers. How did this happen?

But first…. - Miles A.

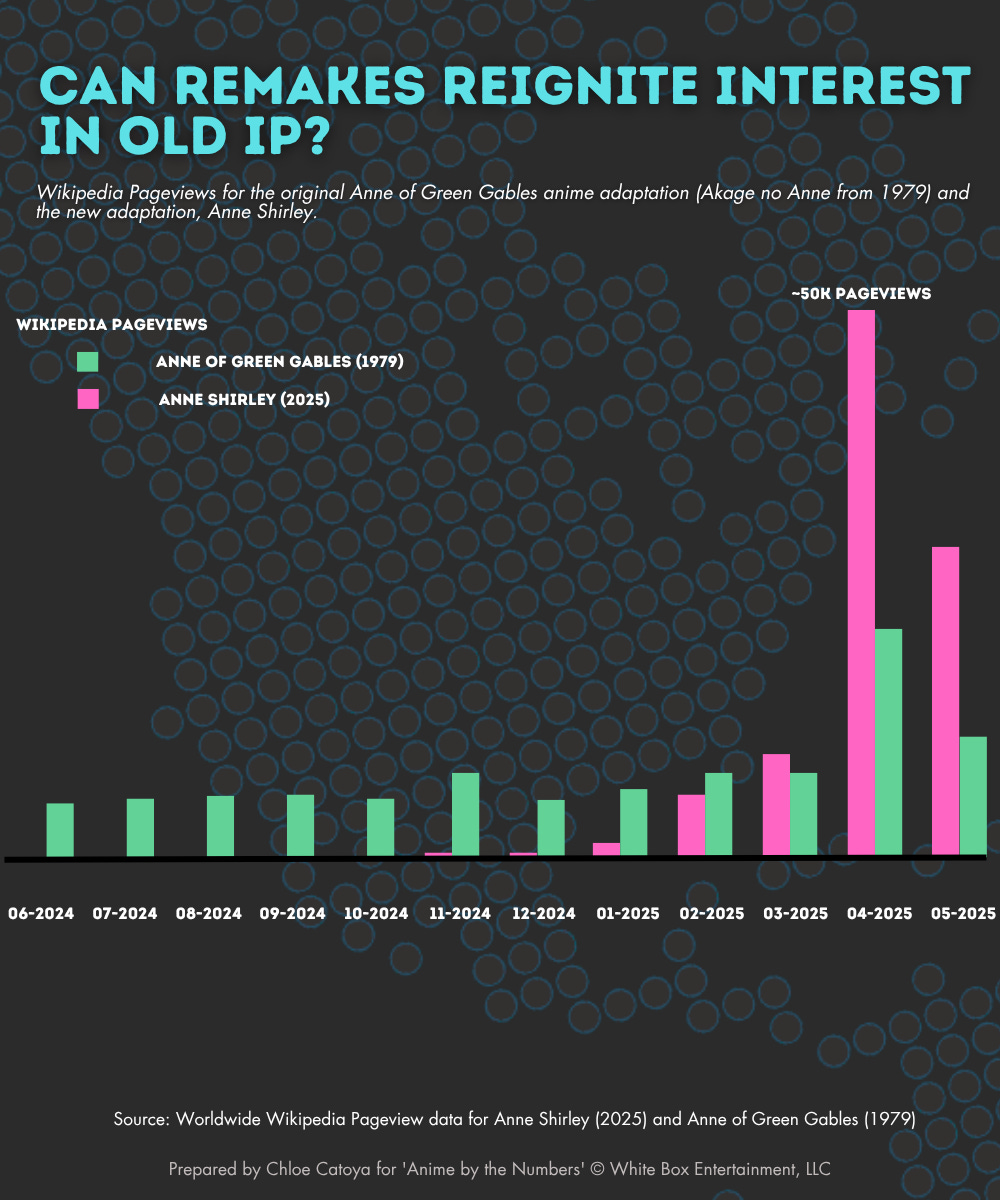

Reboots and remakes are all the rage for major Hollywood media, with mixed success. But anime has a slightly different relationship with this trend, even if these remakes are made for the same purpose—to make new money off of old IP. The currently airing Anne Shirley is the second anime adaptation of the beloved classic novel Anne of Green Gables, the first being Akage no Anne—listed on English Wikipedia as Anne of Green Gables (1979)—directed by Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata.

Unlike most anime reboots, like Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood or Ranma ½ (2024), Anne Shirley and Anne of Green Gables (1979) have fully separate entries on Wikipedia, both from each other and their source material. This allows us to see general interest in the separate adaptations. Wikipedia pageviews, among other metrics, are a good starting measure of general audience interest, which also usually correlates with viewership shifts as well.

Anne Shirley was first announced in November 2024, which we can see is when its Wikipedia page was first created, thus diverting some of the traffic that was going to the 1979 adaptation for that month in error. But when the new anime started airing, genuine interest in Anne of Green Gables (1979) rose as well.

Google trends search data also reflects this trend of the new uplifting the old. In May 2025, Anne of Green Gables (1979) was searched 2x more than it was before Anne Shirley began airing in April. It’s clearly not erroneous searches, either, because during this time, searches for Anne Shirley were 2x higher than the searches for Anne of Green Gables (1979). Additionally, Google categorizes searches for topics based on the user’s search terms so searches for “old anne of green gables anime,” “new anne of green gables anime,” or any phrases like them, were sorted accordingly.

It’s exciting to see interest in older adaptations as new (and well executed) ones bring in new audiences to an IP. If the older version is widely legally accessible, it’s nice to know people are still interested in older pieces of media. - Chloe C.

Anime “abridged” videos, where fans do a parody dub of an anime, are a lost art form these days. Millennials like me quote “I’m at soup” daily, but the kids these days don’t even know what that is. (Yes, there’s plenty of creators still making them, but they don’t nearly have the same impact they used to on the community.)

This is why I was so happy to see a new abridged project, for the Fruits Basket anime reboot, started a few months ago. Maybe the kids will be alright, if clips from this one go viral like they used to back in the day. - Klaudia A.

Local headlines about proposed censorship of books and the internet in different states have set U.S. anime and manga fans into a panic. Will anime be banned in Texas? Will BL be banned in local U.S. libraries? This piece takes a nuanced look into the current state of what the hell is going on with Project 2025 and manga. - Klaudia A.

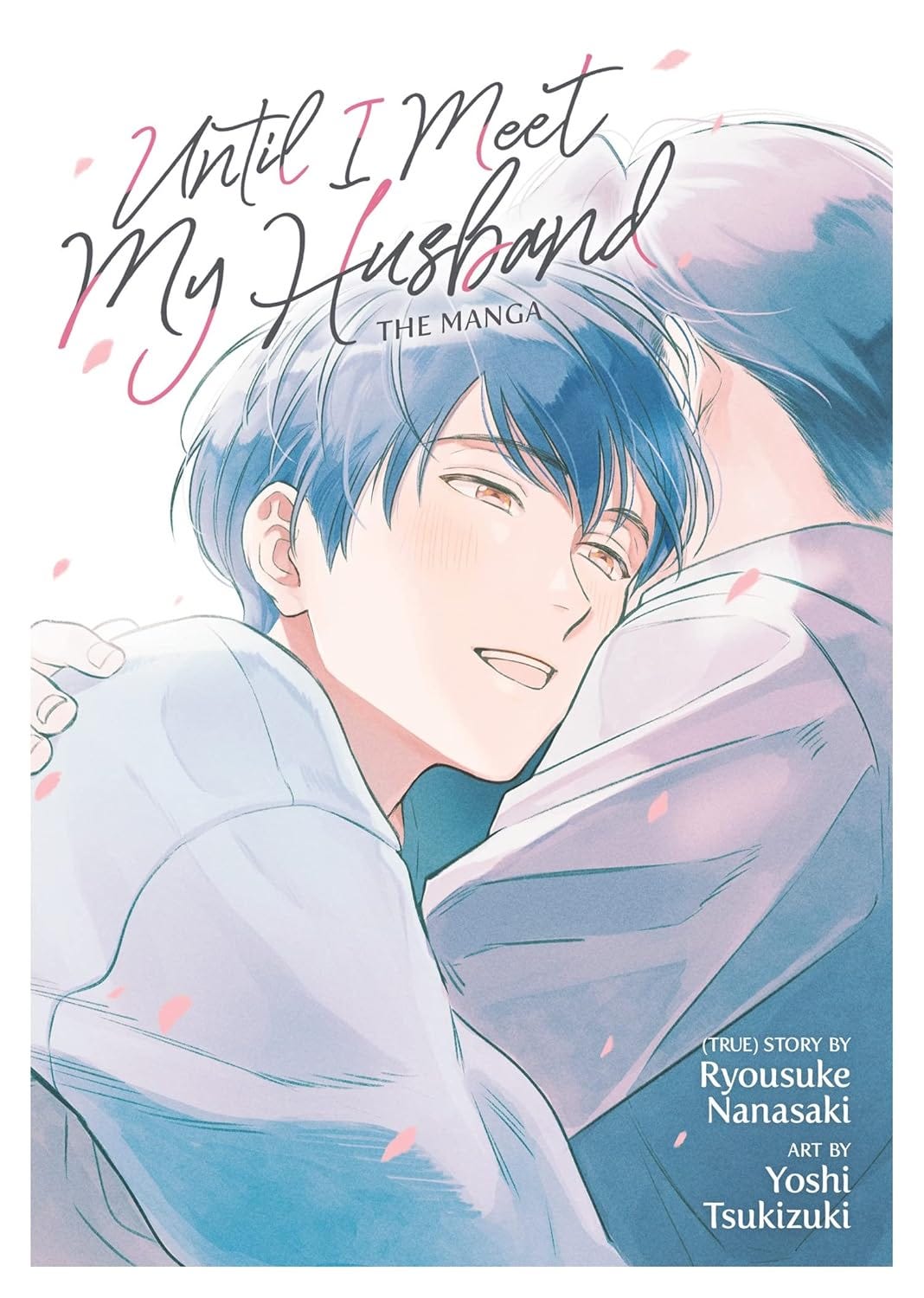

Until I Meet My Husband is the nonfiction manga adaptation of a collection of essays by gay activist Ryousuke Nanasaki. It follows his historic life story as a part of the first religiously recognized same-sex marriage in Japan, recounting all his “firsts” as a young gay man searching for love. This one-shot manga adaptation is illustrated by beloved BL manga artist Yoshi Tsukizuki.

Nanasaki notes in the manga’s afterword that “Until now, I don’t think the lived experiences of gay people and those who seek out the world of BL have lined up. That might be because both parties are seeking different things. But as someone who resides in both worlds, I feel that the team of myself—a gay man—and the BL artist Yoshi Tsukizuki has yielded a truly groundbreaking work.”

I remember reading it right after purchasing the physical copy at Barnes & Noble, and being brought to tears right in the store. It definitely moved me and I think it will move you too! - Leah T.

Rock is a Lady’s Modesty is the latest offering in the time honored anime subgenre of girls’ rock bands at preppy, elite schools. But there’s a cool twist—the protagonist has to pretend she’s a modest, perfect student, when in reality she's more foulmouthed than your questionable uncle.

Absurd cutaways, really great music, and the most toxic potentially yuri situationship make this the hidden gem of the spring anime season. - Miguel M.

Last week, Variety debuted a new report from media measurement and analytics firm Nielsen, giving 35-Day multiplatform ratings for the 2024-2025 TV season. Many in the industry took this as the definitive picture of U.S. TV viewing, because it was the first time that Nielsen’s TV ratings would collate all streaming data, recorded TV, and live broadcast viewership into a single number, backed up with first-party data from the likes of Netflix, Disney, and Roku. Their methodology was accredited by the independent Media Ratings Council, who had been a critic of Nielsen’s stats in the recent past. To say I’d been eagerly awaiting this would’ve been the understatement of the year.

However, according to this report, Dan Da Dan was the most-watched anime in the United States that season. With 2.6M unique viewers from ages 18 and 49 in the first seven months of the 2024/2025 TV season, (September 15 2024 to April 6, 2025), it was notably the only anime to make either Nielsen’s list of the 100 most-watched TV shows amongst U.S. adults, or the top 100 within the 18-49 age group.

But according to our analysis here at White Box over the past year, this doesn’t make much sense. Yes, this number is pretty similar to our best estimates of the unique U.S. Dan Da Dan piracy viewership in December 2024, to say nothing of the substantial Crunchyroll and Netflix legal views, or the additional January binge-watchers. But even so, Dan Da Dan was absolutely not the most-watched anime in the U.S. in this time period–not even close.

[Normally, the rest of our main story would be behind the paywall, but this week, it’s free for all readers! Make sure to subscribe to support our work.]

To qualify for Nielsen’s top 100 TV shows in the 18-49 age category, a show only needed to best Wheel of Time’s 1.9M viewers. With approximately 135 million Americans within that age range, only 1.4% of that population needed to watch a show for it to crack the list. Polygon’s anime audience survey from last year claimed that 42% of Gen Z (who are now mostly over 18) and 25% of millennials watch anime weekly. Even if we’re to say those reported rates are double actual behavior, the list presented by Nielsen does not contend with that behavior.

We’ve talked quite a bit about how profoundly popular Solo Leveling is in the U.S. in this newsletter. While Dan Da Dan was certainly one of the elusive “S-level” anime of last year, in terms of U.S. viewership compared to the likes of Demon Slayer, our internal estimates indicate it was dwarfed by Solo Leveling’s first season, capturing roughly only half of the eyeballs. But Solo Leveling’s first season wasn’t airing during Nielsen’s report time period—its second, even more popular season was airing instead.

According to a press release from Solo Leveling publisher Kakao Entertainment, the anime adaptation’s second season “reigned atop the charts across all Crunchyroll regions” as “the most popular series of the first quarter.” Certainly, if the Nielsen report is looking at viewership within the first 35 days of release, this would be enough to break into the charts just using Crunchyroll data, right? We estimate that slightly more than half of Crunchyroll’s 17 million subscribers are in the U.S. So in order for an anime to pass Wheel of Time’s 1.9M viewers and crack Nielsen’s top 10 list, only about 20% of Crunchyroll U.S. subscribers would have needed to watch Solo Leveling season 2, a wholly reasonable expectation considering the level of promotion and community hype it received. Our research estimates the U.S. Solo Leveling season 2 viewership number to be even higher than that.

So let’s do some quick math on the Nielsen figures. In 2024, Netflix reported that Dan Da Dan received 19.6M “views” worldwide, better understood as “completed series viewed equivalents”. Based on daily top 10 performance, Netflix subscribers in the U.S. were less likely to watch Dan Da Dan than those in Asia, Latin America, or Europe. The U.S. makes up 9% of Netflix’s subscribers, but let’s be safe and say that the U.S. only made up 7% of Dan Da Dan’s total viewership.

Using the average post-launch performance of Netflix exclusive anime from the last two years, we can assume that Dan Da Dan’s Q1 viewership was 15-20% of the six months last reported by Netflix. Then, using piracy data to extrapolate viewership behavior, the median Dan Da Dan viewer watched about 8 episodes, or 66% of the show. We divide the “complete series viewed equivalents” by this to get a sense of the unique viewers. That brings us to 2.4M unique viewers on Netflix – fairly close to the number stated by Nielsen. This calculation shows that Nielsen is outright missing most Crunchyroll and piracy viewership.

For most television, glossing over piracy is probably fine, and matches the report’s incentives. Historically, Nielsen’s primary customers have been advertisers – people who need to know how many people are actually watching a program so they can target customers and assess performance. People who watch Abbot Elementary on bootleg streaming sites aren’t really customers, not when the majority of revenue for these titles comes from commercial spots and licensing from streaming services.

But anime has a deep history with piracy, with U.S. audiences historically relying on less-than-savory methods as the only means of accessing most titles for much of the medium’s popularity. Although most of the justifications fans give for pirating are no longer supported by the data (a topic for another article), tens of millions of Americans visit bootleg streaming sites dedicated to Japanese animation every month. While it’s dropped significantly in the last decade, anime is still more than twice as likely to be pirated as non-anime TV in the U.S. Case-in-point: according to data collected from SimilarWeb, the most popular bootleg anime site received 118 million visits in April from the U.S. By comparison, the most popular pirate site for non-anime TV and movies only received just shy of 20 million hits in April.

By now, I’ve hopefully made you skeptical that the Nielsen figures match actual viewership. But let’s try to figure out why this is happening.

The first and most obvious explanation is the methodology. When it first began, Nielsen would ask a representative panel of Americans to keep a diary of everything they watched on TV, but as technology improved, so did their methodology. In the late 80s, Nielsen incorporated the “People Meter”, a device that would automatically track everything watched on a device. Their panel of People Meter users expanded to 4,000 homes by the end of the decade – just enough to be representative of the U.S. when paired with the diaries.

However, Nielsen began to lose some of their authority status with decision-makers and analysts in the TiVo era of the mid-2000s. It took the company many years to deliver a statistically sound way to capture the new norms and behaviors of people who were now free to record and watch the next day with the ability to skip ads. This only became more complex with the streaming era, when cable cutting led to tens of millions of Americans to switch from cable to using streaming services exclusively. Until recently, every streaming service was something of a black box, with only the occasional “datecdote” from company press releases to go off of.

Even with their massive sample size of diary takers in the Netflix age, Nielsen had challenges with capturing data from young viewers and minority groups. Then audience behavior shifted AGAIN in the pandemic, making the problem worse. The start of the 2020s saw phones become even more popular for video, including long-form media that used to be the exclusive domain of TV.

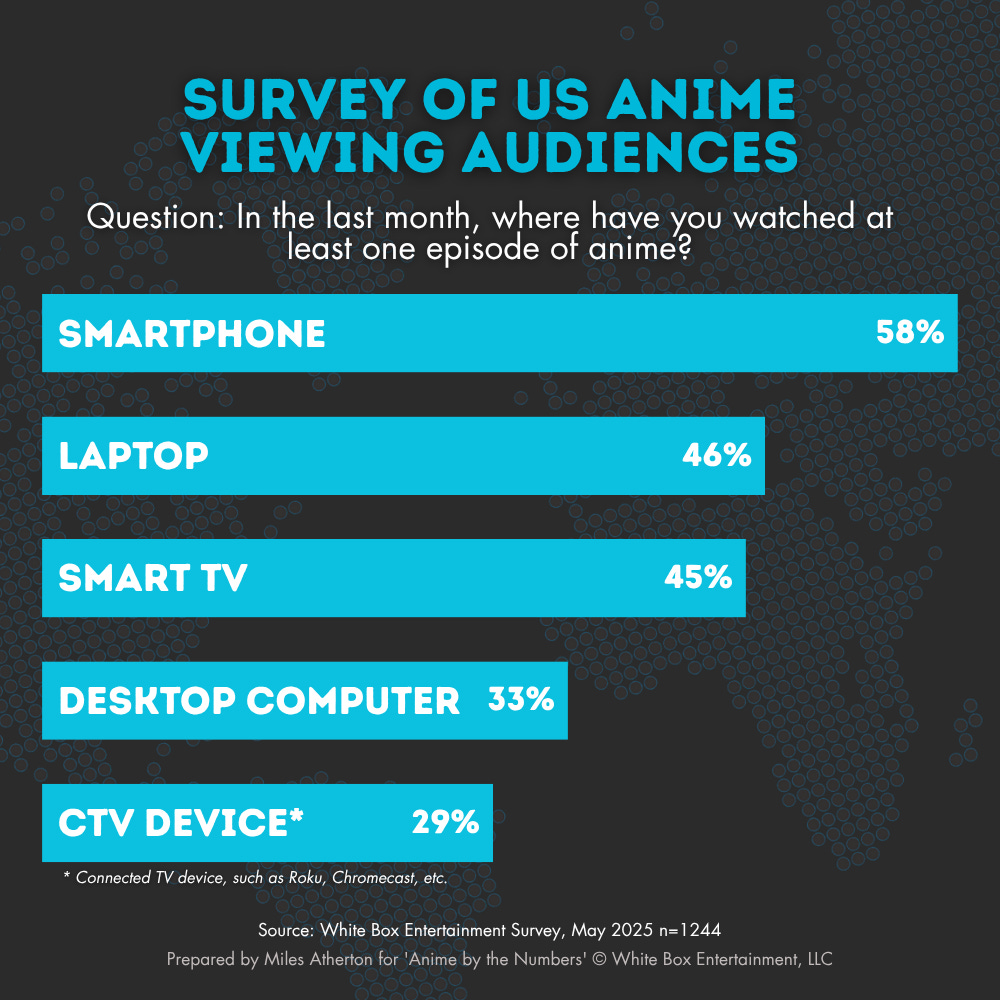

Here lies the issue with measuring anime viewership. Our research indicates that Nielsen does not appear to get any first-party viewership data from anime-specific streaming services such as Crunchyroll or HIDIVE. This issue is compounded by an underrepresentation of anime viewership on smart TVs and connected TV devices like Roku and Chromecast.

Anime viewers are much more likely than your typical Netflix or Disney viewer to watch anime on their phone or computer. Crunchyroll receives roughly the same web traffic as Hulu, despite having only ⅓ of the subscribers. This is wholly at odds with Nielen’s non-diary methods of capturing viewership data, which rely heavily on data shared by CTV devices and smart TVs. This goes doubly so for piracy, which is generally unavailable outside of browser navigation by either of those sources.

To recap:

Anime is more likely to be pirated than other media, which is not factored into Nielsen’s methodology.

Crunchyroll and HIDIVE, the most popular anime-specific streaming services, do not seem to provide first-party data to Nielsen.

Anime viewer behavior does not align with how Nielsen collects viewership data, particularly due to which devices are used. As a result, viewership on any platform without first-party data is not factored in at a commensurate rate.

Until very recently, anime was not acknowledged as a worthwhile artistic or economic investment by western media, despite its rising popularity outside of Japan. This was not entirely a bad thing: for many years, the anime community had something of a punk-rock-but-nerds vibe, a counterculture born from the graphic and subversive nature of the medium’s earliest hits overseas, as well as its roots in piracy as the only means one could experience most titles. Anime being socially “underground” was part of the appeal.

But anime has always been more popular abroad than mainstream western media has liked to acknowledge. In the first week of the 2002/2003 season, Dragon Ball Z was the “#1 program of the week on all cable television with tweens 9-14, boys 9-14, and men 12-24”. Working backwards from TV ratings, the anime-centric block on Cartoon Network, Toonami, was typically the most-watched in its time slot with not just children, but with young adults as well. Even when reduced to just one night a week, Toonami still maintained its place as the top in its timeslot with the 18-34 crowd.

And now Solo Leveling and The Apothecary Diaries dot the shelves of treadmills when I go to the gym. Anime has never needed the decision-makers of the western media world to acknowledge its popularity to become one of the most culturally dominant forms of entertainment, particularly amongst younger audiences.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter that anime is being underrepresented in Nielsen’s data. Their primary purpose is to guide advertisers, and most anime is watched via SVOD or piracy. And while Nielsen’s TV ratings were taken as Hollywood gospel in the 20th century, it’s less clear that the same is true in the streaming era. It seems that the more anime becomes mainstream, the less the traditional structures of western media know what to make of it. - Miles A.

.png)