You almost certainly know about the mushroom cloud, the shock waves, and the flames, but did you know about the black rain that fell an hour after the atomic bomb detonated in Hiroshima?

It’s difficult to imagine the scene in the minutes after the overwhelming flash and noise of the bomb’s detonation. Wounded people cried out for help; those who were still mobile staggered around trying to make sense of what had happened. People tried to save those who were trapped under the endless field of rubble that had once been a thriving little city.

Then the black rain started to fall from the sky. This precipitation — giant drops falling from a sinister cloud of ash and soot and radiation — fell from the spreading mushroom cloud over a wide area, streaking walls and staining clothes. Some deliriously thirsty burn victims drank it in the absence of anything else. Many others felt this poisonous brew burn their skin.

The black rain was the first of many burdens that the people of Hiroshima had to cope with after the bomb’s initial detonation. As the survivors dug themselves out of the rubble, they had to contend with long-term illness, discrimination, and the question of whether and how to rebuild their city.

The atomic bomb initially killed between 70,000 and 140,000 people in Hiroshima. The gap between those numbers — constituting almost one-third of the city’s pre-bomb population — demonstrates how imprecise our knowledge is about one of history’s most well-known events. American Colonel Stafford Warren, who was tasked with coming up with a number, told Congress in 1946 that quantifying the number of dead was impossible:

One very great source of confusion was the fact that the Japanese themselves had no information, no precise data. They did not know what the population of either city was beforehand. They had very little way of telling how many people had survived or had returned to the city.

I am embarrassed by the fact that even though I led a medical party which was supposed to get figures on the mortality, and so on, that we could not come back with any definitive figures that I would be able to say were more than a guess…

I see no way of putting a precise figure on the mortality or how a precise figure can ever be put on the total casualties.

In addition to poor record-keeping, “missing” transient laborers and foreigners, and the chaos of the immediate aftermath of the bomb, it was impossible to determine precisely which deaths to attribute to the bombing.

The initial blast and fires killed tens of thousands of people in the seconds and minutes after the detonation, and many more people perished from burns and other injuries over the next week or two. But that wasn’t the end of the suffering.

Though people dosed heavily with radiation declined quickly, others who had been less severely exposed followed a different course. They might have felt nauseous right after the bombing, but then experienced a false recovery. Their hair might have begun falling out two weeks after their exposure. Fever would hit in the third week, and diarrhea and nose bleeds in the fourth. Some recovered, but many died.

For others, the danger came much later. Thousands of residents, especially children, developed leukemia between two and six years after the bomb hit. Another four or five years later, other cancers started to appear. Women who were pregnant lost their babies at a much higher rate than usual, and many of their children were born with microcephaly (an abnormally small head), which led to developmental delays and seizures.

Those who managed to avoid dying from the effects of the bomb weren’t home free. People whose skin was exposed to the heat of the blast developed thick, painful keloid scars. Others experienced lymph node problems, hypertension, and suffered from strokes as they got older.

Then there was the emotional suffering. Almost everyone in Hiroshima lost someone who was close to them. Most tragically, there were at least 6,000 orphans created by the bomb; about half that number had no relatives left who could take them in. At first, many of these kids had to live under bridges around the train station. They survived by stealing and begging. A month later, when a serious typhoon hit the country, some of these children were swept away from their crude encampment and killed. Though the state eventually put them in orphanages, many had deeply unhappy childhoods.

On top of all this, survivors found themselves discriminated against. They came to be called hibakusha — literally, “bombed person” — and many other Japanese people wanted little to do with them. Hibakusha were considered by many to be damaged goods. Some families hid their scarred children away from the public.

Those who were disfigured dealt with rejection over their appearance, but even people with no outward signs of their experience had to contend with cruelty. Parents didn’t want their children to marry survivors because of a perceived risk of birth defects; employers didn’t want to hire somebody who might develop cancer or be too sick to work at times. Many hibakusha concealed their experiences from others.

Reiko Yamada, a Hiroshima survivor, summed up the rejection she and others felt:

In the past, people told hibakusha, ‘Don’t get married’ or ‘Don’t come close. You are infectious’…

Some people lost their whole family in Hiroshima or Nagasaki, and even though they stayed with relatives, they were stripped of what they used to own and were bullied…

When I visited the homes of hibakusha, some of them would whisper to me: ‘You are a hibakusha, right? I don’t say anything about it to my children.’

One of the biggest questions facing the people of Hiroshima was what to do with a city that had been obliterated.

Hiroshima began its recovery process almost immediately. Two days after the bombing, one of the city’s train lines began running again, although it could only travel one stop from the main station. The streetcars were running by the time an American plane bombed Nagasaki, only three days after the blast in Hiroshima. It took until November to restore electricity to everyone.

But, once the immediate rescue and salvage operations were completed, a bigger question remained: what should the new Hiroshima look like?

The city found itself in a rather unique position in human history. Its urban core was almost completely destroyed, and could be re-envisioned however people wanted. But that destruction was also the result of a world-historical event that would need to be commemorated somehow. Japan also had extremely limited resources; the war had plunged much of its population into poverty. Tax revenue in the late 1940s was 80% lower than it had been before the war.

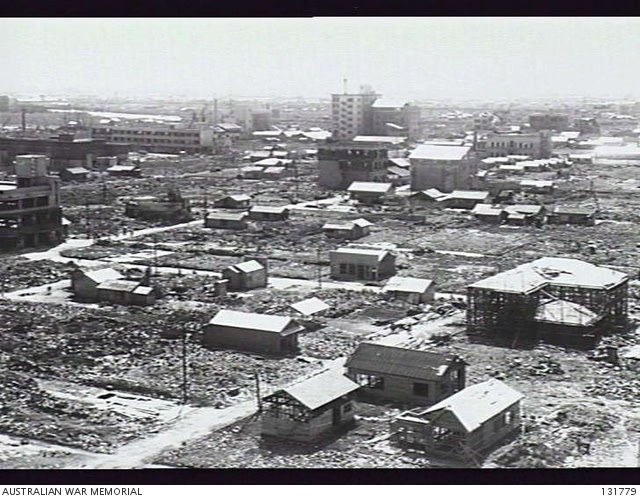

When Emperor Hirohito visited the city in 1947, the city was still mostly in ruins:

In 1946, the local newspaper ran a contest in which it asked citizens to suggest a future for the city. A poet named Sankichi Toge won; his idea was that much of the city should be made into parks, with a museum and monuments to peace. The government essentially adopted his ideas when it passed a law in 1949 declaring that Hiroshima would be a “peace memorial city” that would stand as a monument to the world of the costs of war.

This was a lovely idea — and the Peace Memorial Park on Hiroshima’s central island is an excellent place to visit today — but the plan had real costs. The central island on which the park now exists had been a heavily-populated commercial neighborhood before the bombing. After the bombing, some residents rebuilt their homes there; others assembled small shacks to shelter their families. Having survived an atomic bomb and having found some semblance of normalcy, they were about to have their lives disrupted again.

Many of the people who were relocated for the new park and museum were lower-class or foreign people who had long suffered discrimination. Some of them ended up living in meager shacks without electricity or plumbing until the late 1960s. Landowners in the district were relocated to a new area outside the streetcar network, where their shops were much less likely to thrive. When the memorial cenotaph was unveiled in 1952, organizers hung a giant banner behind it to obscure the desperate shacks. Most of these were cleared out by 1955, replaced by trees and grass.

There was also controversy over what to do with the few structures remaining in the central city. In the photo of Hirohito above, you can see the remains of the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, a building that had housed various expositions and sales in the prewar years. The building’s frame had survived — though everyone in it was killed — due to its construction and its location relative to the hypocenter.

Some viewed the ruin as an eyesore and a reminder of the worst day of their lives; others wanted to preserve the skeletal building as a monument to the bombing. The city took almost two decades to decide what to do about the structure, which began to deteriorate badly. Finally, in 1966, the city decided to reinforce the building, now known as the Genbaku or A-Bomb Dome, as a poignant reminder of the destructive power of war.

Today, Hiroshima is a lovely little city, sitting astride a network of rivers along a stretch of scenic coastline. At its center is an impressive and moving set of parks and memorials commemorating one of the most devastating moments in world history.

The number of people who lived through the bombing 80 years ago is dwindling; soon, there won’t be any first-hand witnesses left. But we should remember that the effects of warfare — especially atomic warfare — can linger long after the smoke dissipates.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are three ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

You can share the newsletter with others:

Share Looking Through the Past

You can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you again next week!

.png)