17 May 2025

Enzo Mari. Putrella, 1958

Enzo Mari. Putrella, 1958

This post reflects on the future of design* —and the role of designers* —in a world where AI is poised to reshape how society works.

Here, by "Artificial Intelligence," I refer to generative AI, mainly, and agentic AI seen as its unmanned version, within the broader definition of the current status of Artificial Intelligence– Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI)– which for the purpose of this post I'd limit to:

An artificial system developed in computer software, physical hardware, or other context that solves tasks requiring human-like perception, cognition, planning, learning, communication, or physical action under varying and unpredictable circumstances without significant human oversight, or that can learn from experience and improve performance when exposed to data sets.1This piece is opinionated. By design.

* up to section ii.iv, "design" and "designer" are capitalised solely in accordance with standard English punctuation, without any additional intended meaning.

updated: May 20, 2025

Disclaimer

This post was not generated by AI.

Artificial intelligence has been used during the research phase, for exploration (RAG) and sources consolidation; AI has also been used to support editing— for English fluency. When used to produce content, AI is explicitely marked.

All data from publicly available sources.

All opinions expressed in this article are solely my own and do not represent the views of any current or former employer.

Content

- i. A vacuous landscape

- i.i Social amplifiers

- i.ii Standard transactions

- i.iii Status quo

- i.iv The AI mirror: exposing the void

- ii. Defining Design

- ii.i Lost ideals

- ii.i.i Enzo Mari

- ii.i.ii Bruno Munari

- ii.ii Refining the Definition

- ii.iii The Designer as a spectrum

- ii.iv designers and Designers

- iii. The Great Misunderstanding

- iii.i A seat at the table

- iii.ii design thinking

- iii.iii design (and build) time

- iii.iv To the point

- iii.iv.i Symptoms of abdication

- iii.iv.ii The decay of platforms, the rise of enshittification

- iv. The AI mirror: exposing the void (reprise)

- v. Back to the Design future

i. A vacuous landscape

In 1993 I was living in Sydney, Australia, and I remember the Artransit2 visual+poetry art posters on buses. One of those stuck with me ever since:

Just then, someone said exactly what I was thinking- "the landscape here is only marginally more interesting than walking around with a paper bag over your head" - which was what I had been thinking. – Synchronicity by Pamela Brown. (original graphic by Wendy Chandler).Which is exactly how I see the design space today.

The visual and material culture that surrounds us is increasingly defined by a suffocatingly dull ugliness.3 From the interchangeable AirSpace4 aesthetic colonising5, 6 our bars & restaurants, rental apartments, fast fashion shops with its predictable palette of reclaimed wood and minimalist furniture to the relentless "blanding" of corporate logos7 into generic sans-serif marks8, 9, and the templated monotony of web interfaces10, 11. Even ads are boring12,.

We have been sucked in a black hole of aesthetic mediocrity.

Of course, this didn’t happen overnight, it's the slow collision of long-simmering forces. In a (Western) world steamrolled by US pop culture, America’s slow, self-referential decline—paired with addiction to immediate and endless endorphins shots—has flattened everything into the same dull average.

This pervasive flat dullness follow us everywhere, the smartphone13 being the undisputed channel of this cultural (if not intellectual) apocalypse.14, 15

If the smartphone is the channel, social media is the master of the message. Ubiquitous across demographics and often overlapping in influence, each social platform carries its own trend cycles and brand-shaping mechanics. But under the surface, they all run on the same engine: a network architecture designed for growth at scale through compulsive frictionless diffusion.

The homogenisation of design, seen from this angle, is the natural outcome of self-optimising interfaces for the imperatives of the attention-based economy. Social media platforms extract value from behaviour, not aesthetics. The more frictionlessly a pattern spreads, the more profitable it is.

Design choices are validated or discarded at massive scale. Instantly.16, 17, 18 Billions of users produce behavioural data in real time, accelerating the feedback loops of mimetism and standardisation. Patterns that win on engagement—likes, shares, dwell time, etc.—are promoted. Those that don’t, are quietly erased.

Designers, knowingly or unwittingly, operate within this economic model. Social algorithms surface certain interactions repeatedly, cultivating expectation. Users internalise these cues and begin to prefer what the system has taught them to expect. Designers, in turn, adopt these patterns to maximise usability and reduce friction*. And the cycle repeats.

- Algorithms shape behaviour by repeatedly surfacing high-performing patterns

- Users grow to prefer and expect these patterns across platforms

- Designers adopt these patterns to meet expectations and drive engagement

- Algorithms reward their usage for delivering predictable results

Self-reinforcing addiction at scale.

We’ve defaulted to a universal paradigm for digital interactions, the infinite scroll. A cascading feed of self-contained media pills—each one primed with standardised engagement triggers: like, share, tag, mention. Repeat. Digital soma.

* [more on this is covered on iii. The Great Misunderstanding]

i.ii Standard transactions

Today, transactional platforms—whether for commerce or service delivery (booking, renting, subscribing, etc.)—operate within a mature, well-established interaction language. This one too rooted in metrics. One language where customer acquisition cost, flows traversal speed, cross-selling ratio, and funnels conversion rate, etc. are the design drivers.

Everything is measured at the millisecond level.

Only partly driven by the uniqueness of the service or product offered, it's the underlying platform that is setting the direction: MS Dynamics 365, Salesforce Commerce Cloud, Adobe Commerce (formerly Magento), Wix, Shopify, Hana, Accesso Horizon, Wordpress, Adobe AEM, to name a few. These platforms are enablers, but also standardisers; they prescribe the language for the relationship with consumers (or users). They define how we browse, compare, book, purchase, return, review, subscribe, cancel, ask for help, leave.

Today’s universal language for any kind of relationship is made of digital interactions—defined by frameworks, libraries, and templates. Efficient. Optimised. Compulsive.

i.iii Status quo

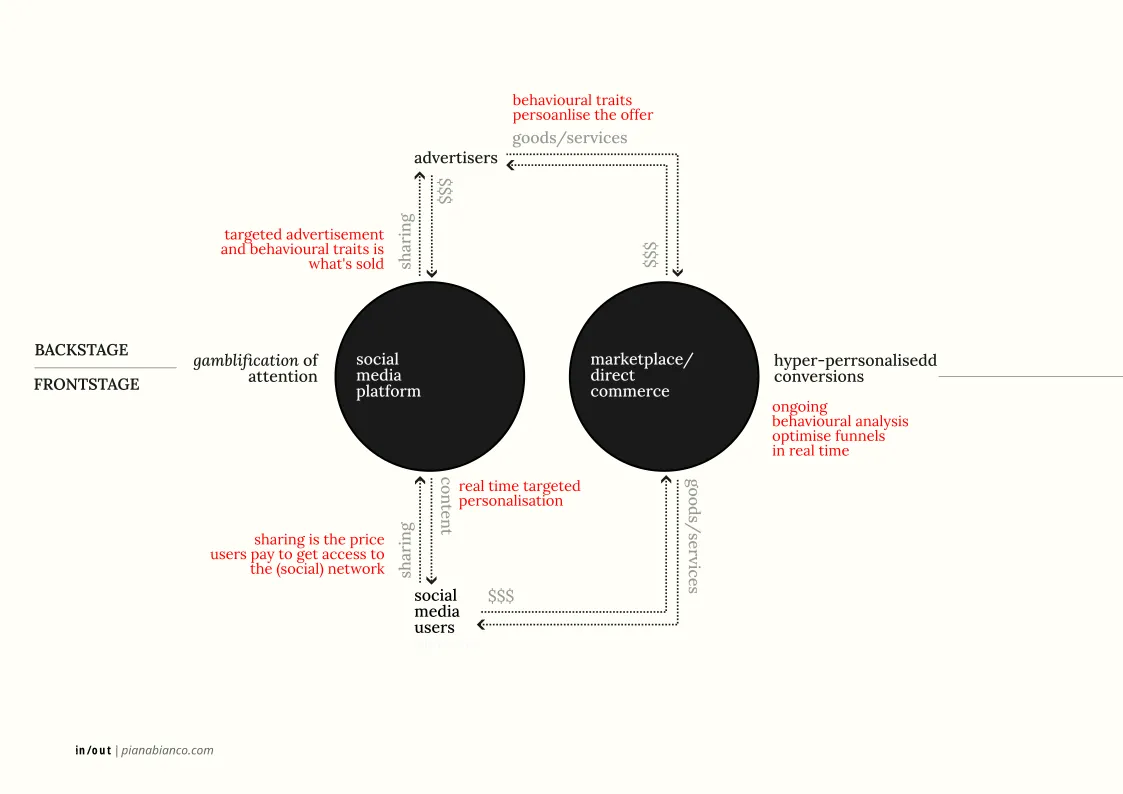

"We think good design is good business." – Thomas J. Watson Jr. IBM’s CEO 1961-1971Reducing contemporary digital economy to its essential dynamics (grossly oversimplifying), we have two interlinked yet distinct foundational forces:

- Commodification of user attention. Social media platforms are designed to capture and retain user attention, while simultaneously extracting endless feeds of behavioural data to be packaged and sold—primarily for targeted advertising.

- Frictionless ubiquitous monetisation. Advertisers—whether brands, retailers, or individual creators—sell both tangible products and intangible services, relying on real-time streams of behavioural insights.

attention economy cycle - apb 2025 (enlarge)

attention economy cycle - apb 2025 (enlarge)From the gamification (gamblification?) of attention, to the hyper-personalisation of the offer (and flows) optimised for maximum conversion, the language is set. Service platforms and transactional flows have settled comfortably into codified phases: register, login, browse, compare, like, share, book/order, buy, pay, consume, (ask for) support, return/dismiss, leave/disengage*. Each phase tightly tweaked.

Real time micro-adjustments compete against growth KPIs—engagement cost, value extraction, probabilistic trend models. For this to be possible, everything has to be formally defined, codified, regulated. This has become the inherent responsibility—and by-product—of the dominant technology platforms governing each phase. From this perspective, the Design System is the tokenisation of one stage of the assembly process—a defining feature of an industrialisation process.

Again, the language is set and fits the bill.

Aesthetic cycles dictated not by taste or cultural shifts, but by real-time engagement metrics and behavioural analytics.

A dominant channel—the smartphone—that tightens the feedback loop with machine-learned precision, reinforcing behaviour while re-aligning interfaces to forecasted preference curves.

A standardised language made to support interactions, built on feeds, cards, taps, swipes, etc. Spreading across domains.

Within rapid cycles of engagement, consumer expectations and preferences are rendered predictably uniform—homologated by design into infinite scrolls of hyper-personalised media pills and real time micro-adjustements at the milliseconds scale. One funnel after another.

Contemporary culture is saturated with mimicry.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Designers borrow styles from Dribbble, Behance, or whatever aesthetic happens to be trending at any given moment (neo-Memphis25 held the crown for a while, to mention one). Clients demand work that resembles what already “works.” They move in synchronised tides.

Brands wrap themselves in the safety blanket of generic aesthetics to minimise perceived risk.

This mimicry is not inevitable; it is a symptom of deeper surrender—an abdication of responsibility for independent thought and critical judgment. This failure is structural, embedded in the incentives of the attention economy itself.

The impulse to mimic is a form of cognitive outsourcing: why ask difficult questions when the market has already “answered” them?

Everyone is obsessed with making it do the same thing." – @worm_emojiAs the offer of design converge toward sameness, so too do the demand: consumer desire becomes acclimated to what is most visible, most repeated, safe. Audiences do not demand what's better; they demand what's familiar. In this context, mimicry is not just a failure of imagination but a social condition.

Designers mirror each other, clients mirror competitors, and users mirror back what they’ve already seen.

Dead internet theory will win, not because bots will take overBut because our posting will be so mimetic. It’ll be indistinguishable from bots. And THEN we will collectively be sick of the feed… but it’ll all just be us… – @HipCityReg

This isn’t the place for a proper political critique of the status quo—and specifically of what we defined here as the attention economy, but the point is: within the logic of this prevailing model (the attention economy, that is), the design of products, services, or “experiences” (if we must) is inevitably calibrated for one purpose: endless extraction of maximum possible value from the consumer.

Through this lens, “user-centred” starts to mean something else entirely.

* [not looking for universality; also not representing sequentiality]

i.iii The AI mirror: exposing the void

The more parametrically standardised and structurally defined the product, the faster the replication. And the more replicable, the more viable (and appealing) automation becomes.

"I’m not sure how to describe it. In a basic way, I felt I was watching a new kind of creature being born, and also watching a generation come face to face with that birth: an encounter with something part sibling, part rival, part careless child-god, part mechanomorphic shadow—an alien familiar." – D. Graham Burnett, Will the humanities survive artificial intelligence?, The New Yorker (April 26, 2025 / accessed April, 27 2025)When ChatGPT released its advanced image generation via the 4o model, I posted something on LinkedIn with a deliberately provocative title. It was, I admit, a little clickbait-ish—but hey, it's the attention economy isn't it? The post drew a fair bit of (interested) outrage.

#ai #4o #ux #ui #design | Alessandro L. Piana Bianco | 203 comments

Do we understand it's over for UI/UX designers? Like, OVER. Total duration of mock-up session: ~1 hour and 20 minutes -- hey, it was 4:30am and I also made a coffee :D Number of iteration prompts: 6 iterations Total number of words in iteration prompts: 842 words #AI #4o #UX #UI #design | 203 comments on LinkedIn

To some extent, this current post is a structured articulation of the point I was trying to make back then— that post wasn't (obviously) about using ChatGPT to crank out a wallet card in an hour.

AI threatens to displace designers from two directions.

The first isn’t new, nor is it unique to AI: it’s the full-stack automation of digital products creation—from brief to deployment. What’s changed is that with AI, the process becomes simpler: it doesn’t require clean, structured, or even complete data. With the potential to autonomously adjust and respond to external changes.

In this sense, AI is less a disruption than a powerful accelerant of an industrialisation26 process that was already running full-steam.

Land Rover Celebrates Production of First New Discovery Sport

Land Rover Celebrates Production of First New Discovery SportThe second direction is more disruptive—and it comes from the people formerly known as consumers (or users). Access to the means of production has (once again) opened up.

It is a defining trait of digitalisation, know how and access to the production tools moved from being the sole domain of companies (and the professionals of each domain), to the hands of a smaller, decentralised class of creators—think influencers, content managers, WordPress themes designers, solo app-preneurs, etc. —who possess just enough skill to operate the tools, and go to market.27

Now, the tool has evolved. The (AI) tool is a dream-to-reality machine, even a basic command of English grants (free) access, use, ownership of the end product; users of the tool don't want to make things, they want to have things.

"The wrong starting point when trying to understand generative AI is to threat what it does as creation. The users don't want to make things, they want to have things. The machine doesn't invent, it assembles. [AI] It's the production line of a commodity producer." – Bryce Elder, Financial Times, (April 5, 2025)

|

|

|

| Prompt: I want you to generate from the attached image a version of this person in the photo in the style of let's say 1970s Belgian comic strips, like the one that you would expect for an adventure, international adventure kind of scenario, as typical of the Belgian comics of the 70s, you know, with those characters, the kid, the dog, the twins, you know, that kind of aesthetics. / Chat GPT 4o, one shot, audio-to-text, provided portrait photo as input / [the reference should be evident to fans de la BD] | Prompt: Cool, now I want you to generate the UI and UX of sorts for a mobile app for a banking services. This app is pretty much just like a card that you keep in your mobile phone wallet. I just want you to provide some, as an idea to start with, of this card showing the global position of this bank client with the typical menus and labels. Maybe some data visualization. It should really work like a sketch, an idea of what it can be, just as a starting point. / Chat GPT 4o, one shot, audio-to-text. | Prompt: Cool, can you now do it with the visual design on top? I mean with the look and feel, not as a wireframe. I want this inside an iPhone and I want this to look like a wallet card. It should have a flat design with pale light colors. It should look sleek and slightly Apple style, if you see what I mean. Just like put the name of an imaginary bank and make it look like a real mobile app, again in the shape of a card in a wallet. / Chat GPT 4o, one shot, audio-to-text. |

Please consider the above one-shot prompt images as illustrative only—provisional artifacts of a consumer-level use case in which digital production is triggered by a generic description.

At the current state of mainstream conversational AI, such outputs remain surface-level phenomena.

The industrial variant of this process will not rest in such immediacy; it will unfold as chains of agentic AIs that alternate between surface-facing conversational interfaces and submerged MCP-like networks of API orchestration—modular infrastructures that echo, remix, and diverge far beyond the template of a prompt.

ii. Defining Design

I'm not assuming general knowledge of the origins of the word design, and by derivation designer, so here's the etymological interpretation of the word design I'm using.

The word "design" entered the English language via the French dessin, which in turn came from the Italian disegno, originally derived from the Latin signum (meaning 'sign').

signum, signi (sign):

sign, mark, tokenclue, evidence

Military: signal, order, command

eventually serving as the core of de-signum

designo, designare (to design):

to delimit, to trace, to markto draw, to represent

to indicate, to allude, to hint

to mark, to label, to indicate

to appoint, to designate to a position

to order, to regulate, to arrange, to organise

The boundary of my definition of "Design" can be then rendered as:

A conscious and visible definition of a space to act on.Within this boundary there's room for diverse voices, some of them are foundational, some are transitional. Two of those voices are more foundational than others, those of Enzo Mari 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 and Bruno Munari. 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41

ii.i Lost Ideals

I'm using Mari and Munari as a (inspirational) reference here, please pardon all simplifications–functional to the clarity of this piece– and not to be intended as a critique of either Mari or Munari.

Enzo Mari. ca. 1974

Enzo Mari. ca. 1974ii.i.i Enzo Mari

Enzo Mari was design's uncompromising conscience. His entire oeuvre was a polemic against the reduction of design to a mere function of the market.

Mari saw design not as styling or commodity creation, but as a fundamental ethical and political act aimed at social improvement and the dissemination of knowledge. He railed against consumerism, planned obsolescence, and the design industry's complicity in producing "shit" – objects devoid of quality, purpose, or respect for labor.

For Mari, quality stemmed from deep knowledge – of history, materials, production – and served a social mission, starkly contrasting with the contemporary obsession with profit and fleeting trends.

His Autoprogettazione (1974) project is a radical manifesto.

By providing open-source plans for self-build furniture, Mari sought to demystify production, empower users, and foster critical awareness of the objects surrounding us. It was a direct assault on passive consumption and the alienation inherent in industrial systems, championing accessibility, durability, and functional beauty.

Mari's work consistently demanded that designers justify their existence through ethical commitment and a contribution to collective well-being.

Mari’s vision must be seen within its historical context—namely, 1970s Italy. Trying to separate Mari’s political views from his work and design ethos would be impractical at best, that said specifically politic angle is not the one I'd like to give focus for my argument.

Bruno Munari. 1972 -- Ada Ardessi/Istituto internazionale di studi sul Futurismo

Bruno Munari. 1972 -- Ada Ardessi/Istituto internazionale di studi sul Futurismoii.i.ii Bruno Munari

Bruno Munari offered a different, yet equally potent, antidote to superficiality.

A polymath– artist, designer, writer, educator– Munari defined the designer as an "objective visual operator," a problem-solver whose primary tool was rigorous methodology, not subjective style.

His goal was the forma esatta (exact form) – the solution that emerged logically and coherently from a deep analysis of:

- function

- material

- technique

- cost

- user psychology

He distinguished sharply between the artist's fantasia (imagination, potentially unrealizable) and the designer's creatività (creativity grounded in reason, producing practical results).

Munari himself embodied a synthesis, a "fantasista creativo*" who channeled imagination through rigorous method. His emphasis on clarity in communication, his use of play and experimentation as modes of learning and discovery, and his embrace of technology as a tool to be understood and creatively applied underscore a vision of design as an intelligent, adaptable, and fundamentally human-centred practice.

His work, from the Macchine Inutili to his pedagogical workshops, aimed to democratise understanding and creativity, fostering curiosity and critical engagement with the world.

Bruno Munari, Macchina Inutile (1956-1968) -- photo Pierangelo Parimbelli

Bruno Munari, Macchina Inutile (1956-1968) -- photo Pierangelo Parimbelli* [creative technologist?]

ii.ii Refining the definition

I'm borrowing from Mari and Munari vision to further refine my definition of "Design", by introducing what I consider as the defining characteristics of a Designer.

Intellectual Curiosity

Curiosity here is about understanding the fundamentals (obvious, yet not common) regarding function, materials (technology), production (processes, cost), and context (social context, industry dynamics, regulations, competitive landscape, etc.). It means willingness to explore, being open to incorporate new learnings as well as killing your idols; it means changing your own opinion on things.

Ethical Purpose

Design is inherently a political act, now more than ever. Today’s designing of digital stuff impacts people lives way beyond what happens on the surface (interface). Social improvement– helping people reach their potential, meet their needs, and actively participate in society– and the dissemination of knowledge (democratising creativity by providing access to information) ethically guide Designers in what they do.

Experimental Play

Experimentation is about play. It is about wearing different hats, playing different roles, step on a stage. It is about tinkering and hacking, it is about measuring, adjusting, playing again. Playing is about remaining actively open to all available realities.

Within a conscious and visible definition of a (design) space, a Designer is an intellectually curious agent of positive change, constantly learning and adapting through experimental play.This is my own definition of a Designer— where the capital "D" serves as a differentiating mark.

ii.iii The Designer as a spectrum

A Designer is someone whose work is shaped by a persistent engagement with those three core traits: Intellectual Curiosity, Ethical Purpose, and Experimental Play. These traits may emerge in any profession—and in any act of making.

If we think of a Designer spectrum, as aggregated layers of the above three core traits, we can play and measure how somebody's scoring on that spectrum.

As a one-shot experiment, let's rank on the Designer spectrum the following entrepreneurs: Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk.*

Prompt: I want you to measure the mentioned entrepreneurs on the Design Spectrum, graphically and structurally describing the reasoning behind the scoring / GPT-4o, one-shot, as input both the Designer definition and the Designer spectrum paragraphs were provided.The Designer definition has been provided as input, as well as the detailed description of the three main traits.

Result: Here's a visual mapping of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk along your defined "Designer Spectrum", scored across the three core traits of a Designer: Intellectual Curiosity, Ethical Purpose, and Experimental Play.

Design Spectrum_ Entrepreneurial Adherence to Designer Traits / ChatGPT 4o

Design Spectrum_ Entrepreneurial Adherence to Designer Traits / ChatGPT 4o| Steve Jobs | 8.3 | Strongest alignment with the Designer definition; particularly high in aesthetic intuition and experimental play. |

| Bill Gates | 7.7 | Ethically driven technologist with deep intellectual foundations but more analytical than experimental. |

| Elon Musk | 7.7 | Technically adventurous and experimentally rigorous, yet inconsistently aligned with ethical purpose. |

| Jeff Bezos | 6.3 | Operational genius with moderate design sensibility; ethical and playful aspects less prominent. |

* see Annex for results from other models

ii.iv designers and Designers*

You can find Designers in any fields, some of them have the "designer' title in the job description, lots of them have not.

But also, you have 9 to 5 designers. Strictly shaped by the nature of the discipline they are tasked with mastering: graphic designers, visual designers, industrial designers, product designers, UI designers, UX designers, service designers, strategic designers, business designers, and so on.

The design field has been decisively moving towards hyper-specialisation– UX copywriters, possibly being one of the most ludicrous examples. With hyper-specialisation came tunnel vision, and a reason to exist shaped by (job title) definition. These designers are entrusted with the sole knowledge required for their specific mansions (i.e. a set of codified tasks).

designers are siloed in vertical streams of competence, sequentially chained together according to the specifics of the goal. The definition of an assembly line.

The industrialisation of the discipline resulted in the necessity for a design department, typically sitting within marketing or under technology, sometimes made of scattered teams across the digital area.

Design departments are made of professional designers (i.e. the word designer is part of their job title), each with their own vertical competence, inherited by the ruling methodology, generally associated with its tool de rigueur.

A system that is optimised for production. Until the next optimisation round.

* from this point and for the rest of this piece, I will differentiate between "Designer" and "designer"

iii The Great Misunderstanding

The industrialisation of the design discipline—restricting the field here to digital design—is the inevitable trajectory of the ruling market dynamics. The design community, for the most part, has compliantly embraced this (i.e. the hyper-specialisation of professional courses and "expertise"). My sense is, few have truly processed what’s been happening; some remain in comfortable denial.

In metrics-obsessed organisations—marketplaces, commerce platforms, subscription-based media—optimisation is pushed to its limit by zeroing in on so-called critical flows (or funnels). You’ll recognise these organisations by the job titles coming with their designers: Design Director, Upgrade & Churn; Design Lead, Onboarding; Renewal Experience Designer; Cross-sell & Upsell Design Lead. Operating on adjustments as recommended by data crunching and algorithms. Real-time, data-driven optimisation isn’t just a strategy—it’s the operating system.

The more you hyper-specialise, the more design becomes procedural. The more procedural, the more codifiable. And once it’s codified—if it’s just data—then algorithms will always outperform humans.42

AI threatens to replace designers precisely because it is the next optimisation round.iii.i A seat at the table

But of course there's another side of design, supposedly more strategic.

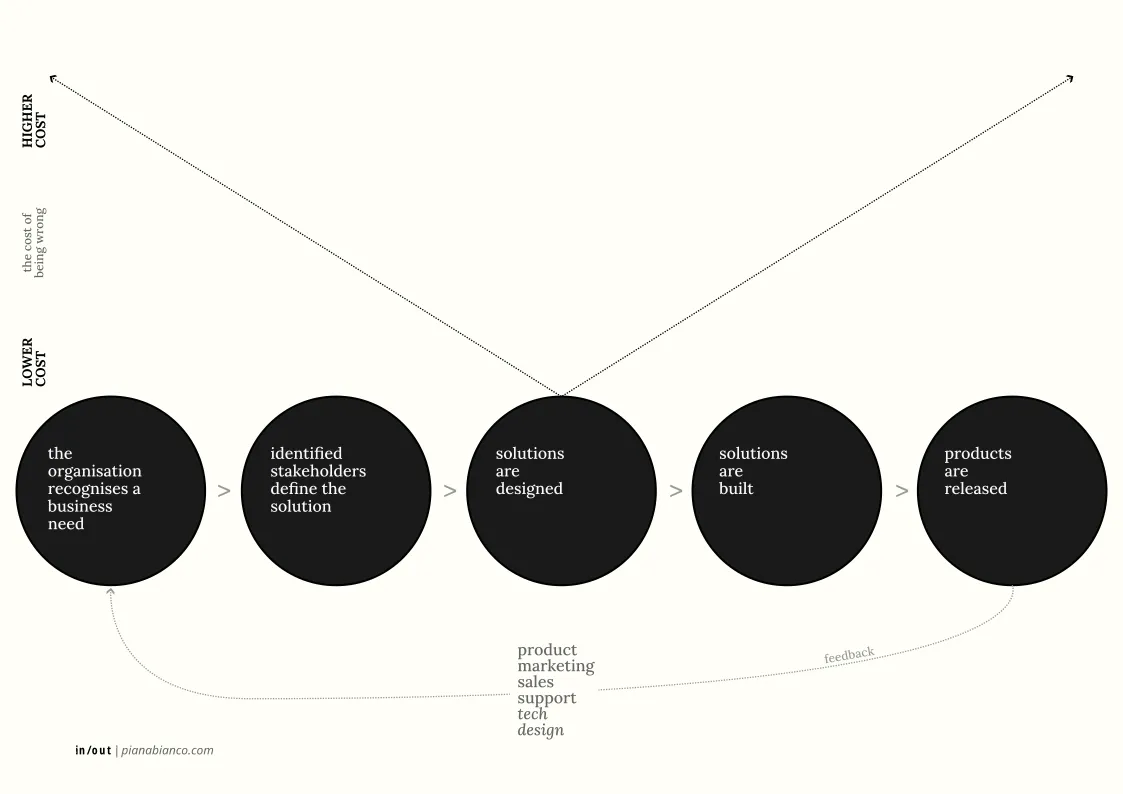

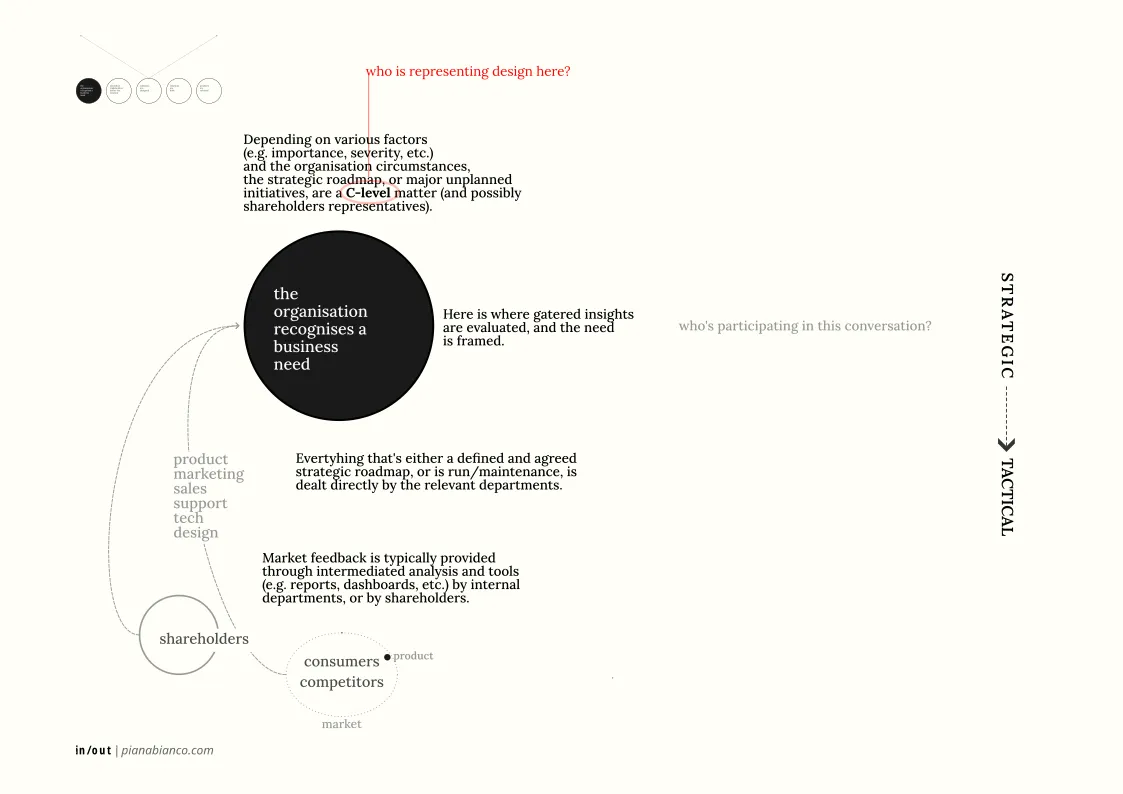

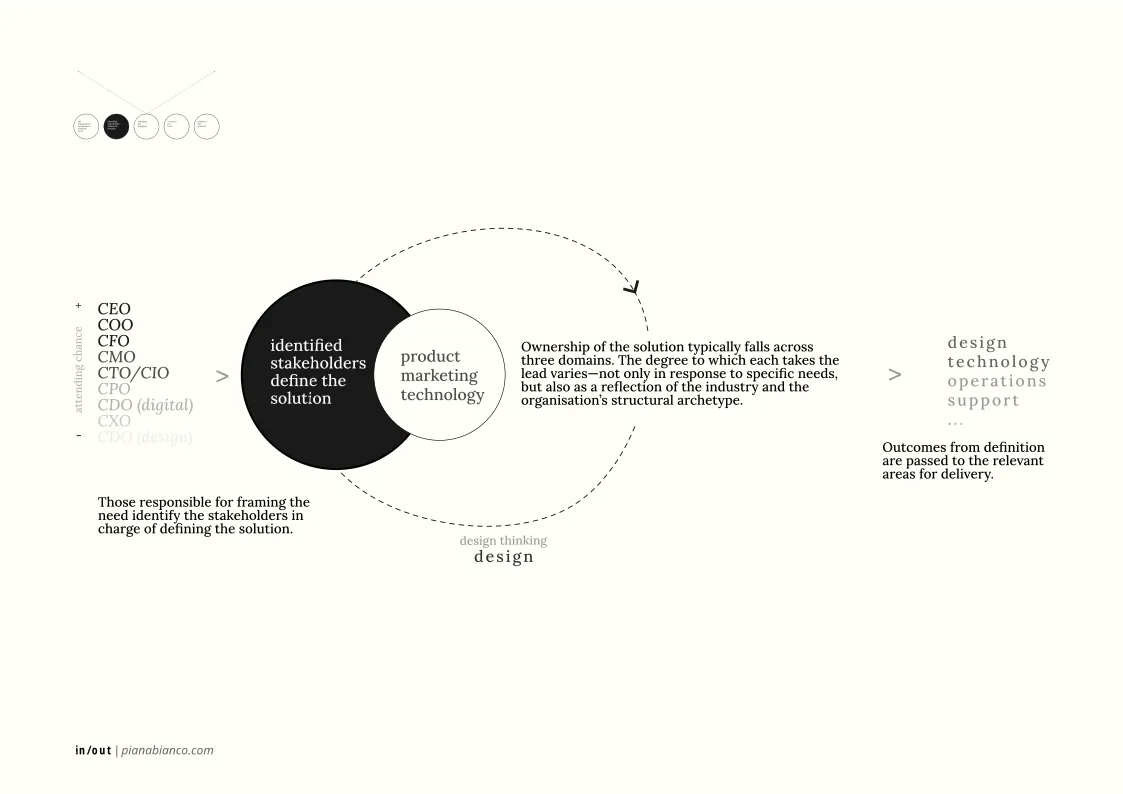

Let's simplify and pretend the following is the typical end-to-end product production flow:

Need recognition > Solution definition > Solution design > Solution build > Product release core production flow - apb 2025 (enlarge)

core production flow - apb 2025 (enlarge)This model is, by design, a simplification—though its underlying logic should be broadly recognisable to most.

If we agree with this end-to-end flow we can map where the cost of being wrong compounds most severely. These points align with the outer edges of the process:

- Upstream—Defining the destination

This is where strategic intent is set.

Decisions around target segments, market entry, business models, or positioning are made here. Misalignment or misjudgment at this stage propagates downstream with exponential cost.

- Downstream—Reaching the destination

This is where outcomes materialise, results is a variable mix of: commercial performance, customer satisfaction, impact on brand, operational and governance complexity, increased risk exposure.

The structure of the model embeds this risk structure, not incidentally.

The highest cost of error is anchored at the points furthest from correction—where strategic missteps are set in motion, and where systemic consequences are realised.In the definition above, "furthest" is used in a broader sense: it refers either to points in the process that involve the highest degree of organisational entanglement—marked by internal dependencies, greater complexity, and thus higher cost (typically upstream)—or, conversely, to those at the outer edge of real-world impact, where outcomes are realised and course correction is no longer feasible without reversing the entire flow (typically downstream).

It should be evident from this model: being at the beginning of the flow is paramount to participate in strategic conversations. In this sense, this type of flow cannot but reflect the structure of the organisation: the upstream inception is a C-Suite-to-Senior Leadership only club.

core production flow / upstream - apb 2025 (enlarge)

core production flow / upstream - apb 2025 (enlarge)Who is representing design at this point?

In the upstream end, design could be represented by any of the following, ordered (empirically) by proximity to the design domain (closest first):

- CDO (Chief Design Officer)

- CXO (Chief Experience Officer)

- CDO (Chief Digital Officer)

- CMO (Chief Marketing Officer)

- CPO (Chief Product Officer)

- CTO (Chief Technology Officer)

In my personal experience (over 20 years, across industries and markets: EU, UK, UAE, KSA), the following are the most common owners of the design conversation (if any) at C-level (most common first):

- CMO

- CXO

- CTO

- CPO

- CDO (Digital)

- CDO (Design)

/ the following has been generated with ChatGPT 4o

Estimated Prevalence of C-Suite Roles

The following is an analysis run with ChatGPT 4o, providing figures on the representation of these roles in organisations, industry data from medium (50–250 employees) and large (250+ employees) entreprises.

| Chief Technology Officer (CTO) | Very Common | Very Common | Very Common |

| Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) | Very Common | Very Common | Very Common |

| Chief Product Officer (CPO) | Common | Common | Very Common |

| Chief Digital Officer (CDO) | Common | Common | Common |

| Chief Experience Officer (CXO) | Emerging | Emerging | Emerging |

| Chief Design Officer (CDO) | Rare | Rare | Rare |

see Annex for more stats on these roles

Design is rarely represented directly; more often, it is mediated through adjacent domains—typically those driven by sales imperatives, such as Marketing (CMO), or those with expansive but diluted mandates, such as Customer Experience (CXO).

iii.ii design thinking*

A super short history of Design Think– from the late 1980s, intentionally skipping the long version starting with Arnold43, 44, and Archer45, 46, to Simon47, and Cross48, 49.

Stanford's Design Thinking

Rolf Faste50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 director of the Design Program at Stanford University from 1984 to 2003, developed design thinking as a formal methodology, a creative approach comprising seven key phases:

- define

- research

- ideate

- prototype

- select

- implement

- learn

Peter Rowe's Design Thinking

It's Peter Rowe's56, 57 book "Design Thinking" that presents a comprehensive examination of design as a fundamental means of inquiry (particularly for architects and planners, characterising the inherent qualities of design as opposed to other forms of inquiry.

"From all perspectives, however, design appears to be a fundamental means of inquiry by which man realizes and gives shape to ideas of dwelling and settlement. – Peter G. Rowe, Design Thinking, (The MIT Press, 1987)IDEO's Design Thinking

Under the leadership of David Kelley, and later Tim Brown, design consultancy IDEO played a pivotal role in popularising design thinking and bringing it to a wider design audience.

David Kelley58, 59 articulated a design thinking process beginning with an "Understand" phase (researching and talking to experts), followed by an "Observation" phase (direct field observation of users to identify innovation opportunities).

Tim Brown60 further popularized design thinking through his influential 2008 Harvard Business Review article and subsequent book "Change By Design".

_

One important, often overlooked, aspect in the origins of Design Thinking is its key contributors did not come from traditional design backgrounds.

John E. Arnold held a BA in psychology and an MS in mechanical engineering, and worked as a mechanical designer and research engineer.

L. Bruce Archer was trained as a mechanical engineering designer and earned a British Higher National Certificate in mechanical engineering.

Herbert A. Simon, a Nobel laureate, had a BA and PhD in political science.

Nigel Cross studied architecture, completed an MSc in Industrial Design Technology, and earned a PhD in computer-aided design.

Rolf Faste had degrees in mechanical engineering, engineering design, and architecture.

Peter Rowe earned both undergraduate and graduate degrees in architecture and urban design.

David M. Kelley began with a Bachelor of Science in electrical engineering before earning a Master of Science in design.

Nearly all of them came from scientific or technical disciplines—predominantly mechanical engineering. Two had formal training in architecture. Most engaged with design not as a foundational discipline, but as a practical extension of their primary field of study.

“Science, at its core, is simply a method of practical logic that tests hypotheses against experience.”–John Michael GreerWhile Design Thinking can be seen as a method for testing user experiences in order to eventually formulate hypotheses, it is most effective when paired with the scientific method—each informing and reinforcing the other in a continuous loop of insight and validation.

The second, more defining point concerns the intended audience of Design Thinking.

Let's look at the de facto contemporary manifesto of the methodology—Tim Brown’s 2008 piece on the Harvard Business Review, which has served as a reference point for the entire movement:

"Thinking like a designer can transform the way you develop products, services, processes—and even strategy."(...)

"Contrary to popular opinion, you don’t need weird shoes or a black turtleneck to be a design thinker. Nor are design thinkers necessarily created only by design schools, even though most professionals have had some kind of design training. My experience is that many people outside professional design have a natural aptitude for design thinking, which the right development and experiences can unlock." – Tim Brown. Design Thinking, Harvard Business Review, (June 2008).

The methodology is intended as a tool (a methodology, indeed) for those who create products, services, or define processes. The "design" part in the term name is misleading (at least in the most common, bland, interpretation), Design Thinking is not intended to be a designers exclusive– quite the contrary; "design" here stands as the engineering design declination of the scientific method.61

Unfortunately, the above interpretation failed to go mainstream—Design Thinking has largely become a tool used exclusively by designers.

I trace the marking of the bonkerisation of Design Thinking with the September 2015 HBR issue. Design Thinking makes it to the cover.

Harvard Business Review (September 2015)

Harvard Business Review (September 2015)While the paragraph above captures the headline—yes, big consultancies acquired design studios—it misses both the intention and the outcome. The consultancy business model is brutally simple: sell billable hours. The more hours, the bigger the invoice. The more people on the project, the more hours. And the more people you manage, the higher you climb. It's a system optimised for scale, not necessarily insight. It’s not exactly a mystery.

The design (thinking) community didn’t get it either. What Harvard Business Review effectively offered was the royal endorsement they had long been seeking—having failed to earn business trust on their own.

In practice, when it comes time to define a solution, a workshop is convened. Post-Its are purchased, Sharpies uncapped. Designers facilitate sessions on functional requirements, product backlogs, customer journeys, personas—whatever the framework of the day calls for.62

At best, designers play the role of enablers and facilitators. But as the distance from the end user grows, so does the dilution of designers insight. The further designers sit from the user, the less they are supposed to know (almost as a design vow).

At worst, designers are reduced to stage designers for the consensus drama.

The long-awaited right to be where decisions are made quickly evaporated when confronted with reality. In the end, the value designers brought to the table was reduced to “knowing the framework”—just as, at the delivery point, the value of UX/UI work has been reduced to knowing the tool.

core production flow / solution definition - apb 2025 (enlarge)

core production flow / solution definition - apb 2025 (enlarge)All of this is more or less accepted—a ritual no one dares to break, as if doing so might jinx the whole process. Until a way to empower products, services, processes people is found. At that point, no facilitators (intermediaries) will be required.

iii.iii design* (and build) time

Now, if at the business strategy, and product strategy stages the cost of correction is higher, once we get to the delivery (design & build) stage– where corrections are intrinsic to those streams– the cost of corrections should get lower. And it does get lower, but with differences.

core production flow / design & build - apb 2025 (enlarge)

core production flow / design & build - apb 2025 (enlarge)Delivery streams carry different weights on the cost–feasibility scale of a solution.

Corrections at build level are expensive. Even without diving into domain specifics, the typical number of dependencies (systems, platforms, services, feeds, etc.) alone should make the intrinsic complexity of this stage self-evident.

_

Finally, design and build are again intermediaries– and providers of enabling tech and ad hoc assets– in the feedback channel from the market (consumers, users) back to stakeholders (business domain owner, e.g. marketing, operations, etc.)– these is, for instance, the case of things such as: multivariate and A/B tests, user research and testing, landing pages and behavioural data, etc.

iii.iv To the point

There might have been a time when designers held a meaningful seat at the strategic table, contributing in shaping decisions rather than simply implementing them. But that seat was surrendered long ago, largely due to designers' persistent inability to define and communicate their distinctive strategic value. As a result designers have been progressively pushed downstream—relegated to the delivery stages—where they remain directly exposed to market dynamics, lacking the protection of strategic relevance.

In the absence of genuine strategic influence, designers have turned to imitation for validation, defaulting to conformity (agin, see René Girard’s theory of mimetic desire to see why this has been a– momentary– winning formula). Instead of developing independent intellectual positions and methodological rigour, opting for superficial imitation, and fashionable aesthetics.

Having neither secured their strategic role nor effectively justified their presence downstream, designers now find themselves increasingly vulnerable.63, 64

iii.iv.i Symptoms of abdication

Let there be no ambiguity: the flatness of form, the aesthetic homogenisation suffocating contemporary design, is a crisis of designers own making.

The profession's retreat from critical engagement has become unmistakable.

designers have abandoned their critical faculties, intellectual curiosity, and ethical considerations, favouring comfortable, tribal narratives.

They have become confined within methodological frameworks adopted uncritically and executed mechanically.

designers have not merely failed to add distinctive value; more significantly, by embracing superficiality and conformity, they have actively participated in betraying the very users they ought to serve.

iii.iv.ii The decay of platforms, the rise of enshittification

Nowhere is this betrayal clearer than in the declining quality and growing dysfunction of digital platforms.65, 66, 67, 68

In recent years, a rising chorus of users, creators, and analysts has voiced concerns about the deterioration in both quality and utility of major digital services.

Services that once felt innovative, user-centric, and even essential—spanning social media, search engines, commerce marketplaces, and beyond—increasingly appear cluttered, manipulative, and primarily focused on extracting value rather than delivering it.

For many, the daily experience of navigating these dominant platforms is now characterised by frustration, demoralisation, and a sense of entrapment within ecosystems that no longer prioritise their interests.

The decline of these platforms is not a neutral "evolution", it is instead the result of deliberate design and business choices. Through this lens, you can see the missed opportunities designers had in influencing these platforms toward genuine user-centricity, highlighting their complicity—or at least their passive acquiescence—in the erosion of quality, trust, and innovation.

iv. The AI mirror: exposing the void (reprise)

The widespread anxiety about AI replacing designers fundamentally misreads the reality.

Artificial Intelligence is not the primary culprit behind the decline of Design; rather, it acts as a mirror, reflecting the discipline’s self-inflicted wounds and revealing how far designers has drifted from their core purpose as Designers.

v. Back to the Design future

most ppl still think of gen images as “tools for artists” when really it’s post art. we’re exiting the scarcity economy of visuals & entering something way weirder—where aesthetics become ambient infrastructure, like wifi. when visuals are free, ubiquitous, & real time reactive, they stop being outputs & start being inputs.— @signüllAI set Design free.*

Mutatis mutandis, AI is the digital equivalent of Mari’s Autoprogettazione. It enables users (consumers) to independently create their own design artifacts, effectively democratising Design itself.

By empowering everyone who has stakes in the outcome to actively experiment, AI opens the door to pursuing Munari’s “exact solution”—grounded deeply in contextual understanding and firsthand knowledge.

When everything can be made out of thin air, and everybody can do that, what will be the differentiator? To move beyond mere personal consumption, Designers will need to differentiate and prove it too.

The key characteristics defining this new breed of Designers will be:

Ethical Agency

Designers will operate within an explicitly opinionated ethical framework. They will start from social impact and expand challenging assumptions from there; they will communicate and market a unique, principled perspective. Designers will refuse to be mere agents of market logic. Designers will be curators.

Intellectual Rigor

Designers will prioritise deep analysis and understanding of the wider context; they will cultivate an engineering curiosity and playful experimentation as tools for innovation. Designers will search for the "exact" solution, not the popular one. Designers will be tinkerers.

Critical Technologists

Designer will use technology (any technology) as a tool to augment critical thinking, structured analysis, data exploration; they will understand its mechanics, limitations, and biases. Designers will be makers.

AI will take over the design department, AI agents will take over designers.

I’m not saying this is the story—but it’s an interesting one.

"Det er vanskeligt at spaa, især naar det gælder Fremtiden."[It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.]

— unknown Danish author (ca. 1937)

* It also set free other things (e.g. coding)

Notes

[1] What is Artificial Intelligence? National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), (accessed April 22, 2025)

[2] ARTRANSIT (accessed on April 14, 2025)

[3] Why Is Everything So Ugly? n+1, The Editors, (winter 2023 / accessed on April 14, 2025)

[4] Welcome to AirSpace The Verge, (August 3, 2016 / accessed on April 14, 2025)

[5] The age of average — Alex Murrell (March 2023 / accessed on April 14, 2025)

[6] Will the millennial aesthetic ever end? Molly Fischer, The Cut, (March 3, 2020 / accessed April 22, 2025)

[7] Why do so many brands change their logos and look like everyone else? Radek Sienkiewicz, (November 18, 2020 / accessed April 17, 2025)

[8] Why Does Everything Look The Same? cheerful.egg, (December 3, 2022 / accessed April 14, 2025)

[9] Why does everything online look the same? Caitlin Dewey, (May 9, 2024 / accessed April 22, 2025)

[10] Investigating the Homogenization of Web Design: A Mixed-Methods Approach - Sam Goree, Bardia Doosti, David J. Crandall, Norman Makoto Su, Indiana University Bloomington, (accessed April 16, 2025) – pdf

[11] The rise of brutalism and antidesign Ellen Brage, School of Engineering, Jönköping University (March 3, 2019) - pdf

[12] All Advertising Looks the Same These Days. Blame the Moodboard Elizabeth Goodspeed, Eye on Design, (March 24, 2022 / accessed April 16, 2025)

[13] 'Our minds can be hijacked': the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia Paul Lewis, The Guardian, (October 6, 2017 / accessed April 24, 2025)

[14] Why Culture Has Come to a Standstill Jason Farago, The New York Times, (October 10, 2023 / accessed April 23, 2025)

[15] A culture stuck on pause in a fast-forward age: Kurt Andersen at TEDxNewEngland (December 5, 2012 / accessed April 23, 2025)

[16] Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture Kyle Chayka, (February 6, 2025 / accessed April 27, 2025)

[17] For who page? Tiktok creators’ algorithmic dependencies Laura M. Herman, International Association of Societies of Design Research Congress 2023 – Life Changing Design (October 2023 / accessed April 24 2025) – pdf

[18] The Pull of the Now Joshua Wilbur, (October 29, 2018 accessed April 24, 2025)

[19] Komar & Melamid: The Most Wanted Paintings on the Web Vitaly Komar, Alex Melamid (1994)

[20] Everything is Ghibli Carly Ayres, (March 27, 2025 / accessed April 24, 2025)

[21] Rene Girard and the Genealogy of Consumerism Metanexus, (May 27, 2008 / accessed on April 16, 2025)

[22] René Girard VII: Mimesis and Consumerism George Boreas, (accessed on April 16, 2025)

[23] The Oracle of Silicon Valley Matthew Gasda, (July 27, 2024 / accessed on April 16, 2025)

[24] Peter Thiel explains how an esoteric philosophy book shaped his worldview Richard Feloni, Business Insider, (November 10, 2018 / accessed on April 16, 2025)

[25] Blue people and long limbs: How one illustration style took over the corporate world Liz Huan, (accessed April 25, 2025)

[26] The industrialization of IT Benn Stancil, (April 11, 2025 / accessed April 25, 2025)

[27] Disruptions in Media Doug Shapiro, (March 2025 / accessed May 2, 2025)

[28] Enzo Mari: A rebel with an obsession for form The New York Times, (October 2, 2008 / accessed on April 12, 2025)

[29] Enzo Mari, Industrial Designer Who Kept Things Simple, Dies at 88 The New York Times, (October 30, 2020 / accessed on April 12, 2025)

[30] Enzo Mari obituary The Guardian, (November 1, 2020 / accessed on April 12, 2025)

[31] Revisiting Enzo Mari, the Design Maverick Who Left a Clear Message to Today’s Designers Eye on Design, (November 16, 2020 / accessed on April 12, 2025)

[32] The Communist Designer, the Fascist Furniture Dealer, and the Politics of Design The Nation, (February 20, 2021 / accessed on April 12, 2025)

[33] Enzo Mari, the designer who hated the design industry

Financial Times, (March 22, 2024 / accessed on April 12, 2025)

[34] Critical Understanding Through Practice: “Autoprogettazione” by Enzo Mari (1974) Mariabruna Fabrizi (April 18, 2016 / accessed on April 17, 2025)

[35] Enzo Mari: Design for the people Rakesh Ramchurn, Architects’ Journal (April 16, 2024 / accessed April 17, 2025)

[36] Bruno Munari Domus (accessed on April 14, 2025)

[37] Munart (accessed on April 14, 2025)

[38] Bellezza: le mediazioni. La bellezza 1880-1967, Almanacco Letterario Bompiani 1967, p. 48, Valentino Bompiani Ed.

[39] Come nasce il designer. La Stampa, Year 104, No. 96, p. 7 (May 8, 1970)

[40] Cronache del design. Tra artisti e designers. La Stampa, Year 104, No. 227, p. 13 (October 23 , 1970)

[41] Cronache del design. L'estetica con i multipli. La Stampa, Year 104, No. 251, p. 17 (November. 20,1970)

[42] Dumb statistical models, always making people look bad Jessica Hullman, Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science, (April 18, 2025 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[43] John E. Arnold

[44] Creative Engineering. Promoting Innovation by Thinking Differently John E. Arnold, a posthumous publication of Arnold’s course materials from the summer seminar called “Creative Engineering.” (accessed May 14, 2025)

[45] L. Bruce Archer

[46] The structure of design process, L. Bruce Archer, School of Industrial Design Royal College of Art, (1968 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[47] Herbert A. Simon

[48] Nigel Cross

[49] Designerly ways of knowing Nigel Cross, Design Studies, vol 3 no 4, (October 1982 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[50] The Role of Visualization in Creative Behavior Rolf A. Faste, Engineering Education, (November 1972 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[51] Seeing it Different Ways: The Role of Perception in Design Rolf A. Faste, IDSA Papers, Industrial Designers Society of America, (1981 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[52] Perceiving Needs Rolf A. Faste, SAE Journal, Society of Automotive Engineers, (1987 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[53] An Improved Model for Understanding Creativity and Convention Rolf A. Faste, SME Resource Guide to Innovation in Engineering Design, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, (1993 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[54] A Creative Balance Rolf A. Faste, ASEE Prism, American Society for Engineering Education, (June 1993 / / accessed May 14, 2025)

[55] Ambidextrous Thinking Rolf A. Faste, Innovations in Mechanical Engineering Curricula for the 1990s, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, (November 1994 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[56] Peter Rowe, Harvard page (accessed May 14, 2025)

[57] Peter Rowe, Surba (accessed May 14, 2025)

[58] Davide Kelley, IDEO page (accessed May 14, 2025)

[59] Ideo’s David Kelley on “Design Thinking” Linda Tischler, Fast Company (February 1, 2009 / accessed May 14, 2025)

[60] Tim Brown IDEO page (accessed May 14, 2025)

[61] Box102: Third Time Unlucky Tobias Revell, The Bounding Box, (November 8, 2023 / accessed May 16, 2025)

[62] Design Thinking, Examined Pentagram, (23 February 2018 / accessed May 16, 2025)

[63] Are we training these tools to replace us? r/UXDesign - Reddit, (February 15, 2025 / accessed on May 16, 2025)

[64] BOX106: What happens when everyone is a designer? Tobias Revell, The Bounding Box, (January 17, 2025 / accessed May 16, 2025)

[65] Pluralistic: How monopoly enshittified Amazon Cory Doctorow, Pluarlistic, (November 28, 2022 / accessed May 16, 2025)

[66] ‘Enshittification’ is coming for absolutely everything Cory Doctorow, The Financial Times, (February 8, 2022 / accessed May 16, 2025)

[67] The ‘Enshittification’ of TikTok Cory Doctorow, Wired, (January 23, 2023 / accessed May 16, 2025)

[68] The Coming Enshittification of AI James Ryan, The Journal of Business and Artificial Intelligence, (December 26, 2024 / accessed May 16, 2025)

Further reading

Discovering Design: Explorations in Design Studies, Richard Buchanan.

University of Chicago Press (1995) - ISBN 9780226078151

Design Discourse: History, Theory, Criticism, Victor Margolin. University of Chicago Press (1989) - ISBN 9780226505145

Designing Designing, J.Christopher Jones. Phaidon Press Ltd (1991) - ISBN 9781854541505

Caps Lock, Ruben Pater. Valiz, Asmterdam (2021) - ISBN 9789492095817

Who Can Afford to Be Critical?: An Inquiry into What We Can’t Do Alone, as Designers, and into What We Might Be Able to Do Together, as People, Alfonso Matos. Set Margins' publications (2023) - ISBN 9789083270630

Desertions with Enzo Mari in America, Giovanna Silva. a+mbookstore edizioni (2021)- ISBN 978-8887071870

What Design Can’t Do: Essays on Design and Disillusion, Silvio Lorusso. Set Margins' Publications (2024) - ISBN 9789083350134

Autoprogettazione?, Enzo Mari - ISBN 9788887942675

Design as Art, Bruno Munari. Penguin Classics (2008) - ISBN 9780141035819

The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, Edward R. Tufte. Graphics Press (1997) - ISBN 9780961392147

Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming, Anthony Dunne. The MIT Press (2013) - ISBN 9780262019842

L'arte del digital design. Progettare per i nuovi media, Fabrizio Vagliasindi. Franco Angeli (2003) - ISBN 9788846446152

Managing Strategic Design, Ray Holland. Red Globe Press (2014) - ISBN 9781137325945

La guerra de las plataformas, Carlos A. Scolari. Editorial Anagrama (2022) - ISBN 9788433916686

How America Lost Its Mind Kurt Andersen, The Atlantic, (September 2017)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History, Kurt Ardensen (2020) - ISBN 9781529108101

Addiction by design, Natasha Dow School, Princeton University Press (2012) - ISBN 9780691160887

Careless People. A story of where I used to work, Sarah Wynn-Williams, Macmillan (2025). - ISBN 1035065932

Overcrowded: Designing Meaningful Products in a World Awash with Ideas, Roberto Verganti. The MIT Press (2017) - ISBN 9780262035361

Brave New World, Aldous Huxley, 1932 - various edtions

The Sciences of the Artificial, Herbert A. Simon, The MIT Press, 1969 - ISBN 9780262190510

Design Thinking, Peter G. Rowe, The MIT Press, 1987 - ISBN 0-262-68067-X

Design Thinking, Tim Brown, Harvard Business Review, June 2008

Skin in the game, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 2018 - ISBN 9780141982656

✺

Annex

Interaction design patterns: a selection

What follows is a selection of interaction design patterns that, between 2010 and 2025, achieved global ubiquity across web and mobile platforms—serving as both the visual grammar of the digital age and, increasingly, the user-facing mechanics of enshittification.

- Hamburger Menu (Collapsed Menu Icon)

- Infinite Scroll (Endless Scrolling)

- Pull-to-Refresh

- Card UI

- Swipe Gestures (Tinder-style Left/Right)

- Floating Action Button (FAB)

- Stories Format (Ephemeral, Sequential Content)

The following has been generated using ChatGTP 4.5 and Gemini 2.5 Pro.

Edited by the author.

The Hamburger Menu refers to an icon, typically composed of three parallel horizontal lines (☰) and placed of the top corners of the interface, used as a button to toggle a hidden navigation menu or panel.

The hamburger icon's design dates back to 1981, created by interaction designer Norm Cox for the Xerox Star personal workstation, one of the earliest graphical user interfaces (GUIs). Cox designed it to be a simple, "road sign" like graphic, memorable and visually mimicking the list of menu items it would reveal. It was intended as a container for contextual menu choices within the Star interface.

The icon also made a brief appearance in Microsoft Windows 1.0 in 1985 before disappearing again.

Despite its early origins, the hamburger icon largely fell into obscurity for nearly three decades. Its resurgence began around 2009-2010, driven primarily by the constraints of mobile interface design. Its widespread adoption and popularisation were significantly accelerated when Facebook implemented it in its mobile app around 2010.

From a user experience standpoint, the primary benefit of the hamburger menu is its ability to create a clean, uncluttered interface by concealing navigation elements.

The main usability weaknesses center on reduced discoverability and increased interaction cost. The hamburger menu is not typically classified as a "dark pattern" in the sense of being intentionally deceptive or manipulative. Ethical concerns are more related to its potential negative impact on usability and accessibility.

Infinite Scroll (endless scrolling) - 2006

Infinite scroll, also known as endless scrolling, is a web and mobile design technique where new content is automatically and continuously loaded at the bottom of a page (or feed) as the user scrolls downwards. This eliminates the need for traditional pagination controls, (e.g. next page) or numbered pages links, creating an apparently seamless and potentially unending stream of information.

The concept of infinite scroll was developed by Aza Raskin in 2006.

Raskin, a user experience (UX) and interface designer, initially conceived of the pattern as a way to improve the user experience of navigating large sets of content, such as web search results, by removing the friction of clicking through pages.

Despite its conceptualization for the web, infinite scroll did not achieve immediate widespread adoption. Its popularity surged significantly in the mid-2010s, coinciding with the proliferation of touchscreen smartphones. The swiping gesture inherent in mobile navigation proved a much more natural fit for continuous scrolling compared to the precise clicks required for small pagination buttons on early mobile web interfaces.

Infinite scroll is now a standard feature on major social media platforms like:

- TikTok

- YouTube

Infinite scroll significantly altered user behavior patterns. It fosters continuous, low-friction browsing, encouraging users to consume large volumes of content without interruption-- users engaging with infinite scroll tend to scan content more rapidly and focus less intently on individual items. By automatically loading more content, it removes the explicit decision point of clicking "next", potentially leading to longer engagement sessions.

The influence of infinite scroll on subsequent design has been profound. It became the de facto standard for content feeds across social media, news aggregation, and image-heavy sites.

More broadly, its success reinforced a design focus within many organizations on maximizing user engagement and time-on-site metrics. Beyond the usability weaknesses related to navigation, control, and footer accessibility, infinite scroll poses accessibility challenges if not implemented with care.

Infinite scroll is widely criticized for its addictive nature: it effectively exploits innate psychological mechanisms. The lack of stopping cues plays on the "unit bias"—our natural inclination to complete a task or reach the end of a unit—but provides no end.

Simultaneously, the unpredictable nature of the next piece of content delivers variable reinforcement, activating the brain's dopamine reward system much like a slot machine. This combination fosters compulsive, mindless scrolling behavior, often referred to as "doomscrolling".

Research and anecdotal evidence link this pattern to negative mental health outcomes, including user regret, anxiety, sleep deprivation, and diminished attention spans.

The inventor, Aza Raskin, has publicly expressed deep regret over his creation, describing this as technology designed not just to help, but to deliberately keep users online, effectively "hunting" them by leveraging asymmetric knowledge of human psychology.

Pull-to-Refresh - 2009

Pull-to-refresh is a common touchscreen gesture primarily used in mobile applications. It allows users to manually trigger a content refresh of a list or feed by swiping downwards when they are already at the top of the view. The gesture typically involves pulling the content down past its resting position, revealing a visual indicator (like a spinning loader or an arrow icon) that signals the refresh action is being initiated; releasing the screen then triggers the data update.

The pull-to-refresh gesture was developed by software developer Loren Brichter, most notably recognized for his work on the early and influential Twitter client, Tweetie. It was introduced within the Tweetie app, likely around the time of Tweetie 2.0's release in late 2009 or early 2010.

Brichter's motivation stemmed from a desire to optimise the limited screen real estate on early smartphones. Initially, the user experience was lauded. The gesture was praised for its convenience, intuitive feel, and efficiency in saving screen space. It felt like a natural extension of the user's intent; scrolling to the top often implies a desire to see the newest content, making the refresh action logically coupled. It also provided users with a sense of control, allowing them to manually ensure the content they were viewing was current.

Pull-to-refresh quickly became an ingrained behavior for mobile users seeking updated content in feeds and lists.

As mobile devices and networks became faster and apps began implementing automatic background refreshing, the necessity of a manual pull-to-refresh action diminished in some contexts, making it feel redundant.

Ethically, pull-to-refresh faces criticism similar to infinite scroll, primarily concerning its potential to foster addiction. The comparison to a slot machine lever is frequently invoked, highlighting the pull-wait-reward loop that can condition users into compulsive checking. This mechanism taps into the desire for novelty and information, contributing to the addictive cycle of social media and email checking. Loren Brichter has expressed regrets about the unintended downsides, specifically acknowledging the addictive potential and stating he lacked the maturity to fully consider these implications during its development.

The success of pull-to-refresh illustrates how an interaction designed for usability (saving screen space, intuitive action) can inadvertently facilitate problematic usage patterns. Its intuitiveness, derived from linking the refresh action to the natural gesture of scrolling to the top, made it easy to learn and adopt. Yet, this very seamlessness and the repetitive physical motion, combined with the variable reward of new information, created a potent mechanism for habit formation.

Card UI - ca. 2010

Card UI refers to a design pattern where information is presented within distinct (typically) rectangular containers that visually resemble physical cards (like playing cards or index cards). Each card encapsulates related content elements—such as an image, title, text description, and action buttons—pertaining to a single topic, item, or entity. Rarely used in isolation, cards are usually arranged in collections, forming grids, lists, or streams that allow users to browse multiple items.

While the concept isn't tied to a single invention date, its prominence in digital interfaces grew significantly during the early 2010s. Platforms like Pinterest, with its image-centric grid layout, were early pioneers in popularizing card-based displays. Social media feeds, notably Facebook's News Feed and Twitter's timeline, also adopted card-like structures to present discrete posts containing mixed media types.

The pattern was formally codified and gained substantial traction with the introduction of Google's Material Design language in 2014, which defined cards as a fundamental component for displaying content and actions about a single subject. Microsoft had also explored similar concepts earlier with the tile-based interface of its Windows Phone (Metro UI) and subsequent Flat Design principles, which emphasized content blocks. Card UI represents an evolutionary pattern, refined and popularised by design teams at major tech companies rather than being attributable to a single inventor.

Card UI significantly impacts how users interact with collections of content, each card perceived as a self-contained piece of information. By grouping information into discrete visual units, cards greatly enhance scannability, allowing users to quickly browse and identify items of interest, particularly when dealing with heterogeneous content types (images, text, video). This modularity often encourages interaction, as cards typically serve as entry points to more detailed views or related actions. The self-contained nature also makes individual cards easily shareable or manipulable (e.g. saving to a collection, sorting).

The user experience benefits of Card UI are numerous. The chunking of information reduces cognitive load and prevents overwhelming "walls of text". When implemented well, particularly with strong visual elements like images, cards are aesthetically pleasing.

However, Card UI is not without potential drawbacks. Poor implementation can lead to a cluttered appearance, especially if cards contain too much information or lack sufficient surrounding whitespace. Card layouts, particularly grid-based ones, can sometimes de-emphasize the hierarchy or intended order of content if not carefully designed.

Card UI has become a foundational element of modern interface design. It is a staple in content aggregation sites, e-commerce platforms, dashboards, social media feeds, and many other application types.It is a core component of major design systems like Google's Material Design.

Swipe Gestures (Tinder-style left/right) - 2012

This pattern refers specifically to the mobile touchscreen gesture popularized by the dating app Tinder, where swiping a card-like UI element horizontally indicates a binary choice. Typically, swiping the card to the right signifies approval, interest, or "liking," while swiping it to the left signifies rejection, disinterest, or dismissal. This interaction is primarily used for rapid evaluation and decision-making on a sequence of discrete items, such as user profiles, product suggestions, or content pieces.

The swipe-left/swipe-right gesture gained global recognition following the launch of Tinder in 2012. The specific implementation is often credited to Jonathan Badeen, one of Tinder's engineers/designers, who, along with co-founder Sean Rad, drew inspiration from the physical act of sorting through a deck of cards. When experimenting with physical cards, the natural inclination was to toss or swipe the top card aside to reveal the next one. Tinder combined this intuitive gesture with a "double blind opt-in" mechanism, meaning communication between users is only enabled if both parties independently swipe right on each other's profiles.

The pattern originated and was initially implemented on mobile platforms (iOS and Android). Its success was immediate and profound. The terms "swipe right" and "swipe left" quickly permeated popular culture, becoming shorthand for expressing approval or disapproval in various contexts. The core interaction pattern was subsequently adopted by numerous applications beyond the dating sphere, utilized for tasks involving curation, quick selection, or binary filtering of items.

The Tinder swipe gesture dramatically influenced user behavior, particularly in the context of online dating and selection tasks. It enables extremely rapid evaluation and decision-making, often based primarily on visual information presented on the card.This speed can lead to judgments that feel superficial or impulsive. The interaction transforms the browsing process into a gamified experience, characterized by simple actions and the variable reward of receiving a "match". This gamification, combined with the simplicity of the gesture, can make the interaction highly engaging, even addictive.

From a user experience perspective, the swipe gesture provides a fast, efficient, and often described as "fun" method for sorting through a large number of options. The gesture itself is simple and leverages the natural swiping motions common on touchscreens, making it feel intuitive. For straightforward binary choices, it significantly reduces cognitive load compared to more complex interfaces. The associated "double opt-in" system effectively reduces the volume of unwanted messages, a common issue on traditional dating platforms. Some analyses suggest it reinvigorates embodied intuition or "gut feeling" in the selection process, contrasting with the more analytical approach of older dating sites.

However, the negative UX implications are substantial. The emphasis on rapid, visually driven decisions is frequently criticized for encouraging the objectification and commodification of individuals (in dating apps). The focus on appearance can exacerbate societal pressures related to beauty standards. The highly engaging and potentially addictive nature of the swipe-match loop can lead to excessive app usage.

Ethically, the Tinder-style swipe is one of the most heavily scrutinized patterns of this era. It is frequently implicated in promoting superficiality and a "consume-and-discard" mentality, particularly in the sensitive context of human relationships.

Algorithms operating behind the scenes, such as Tinder's reported use of an Elo rating to rank user desirability or features like smart photos that optimise profile pictures for maximum likes, raise further ethical concerns about manipulation, fairness, and the algorithmic reinforcement of potentially narrow beauty standards. Monetisation strategies built around the swipe mechanic, such as charging users to undo left swipes or see who has swiped right on them, can be seen as exploiting the very user behaviors (like impulsivity or curiosity) that the core design fosters. Qualitative research suggests the interface design impacts users' dating priorities and interaction preferences, potentially shifting focus away from meeting matches towards the engaging swiping mechanism itself. Due to its addictive qualities and potential for psychological manipulation, the pattern is often discussed in the context of dark patterns research.

The success of the Tinder swipe mechanism lies significantly in its masterful gamification of the choice process. By reducing complex decisions to a simple, repetitive physical action with immediate feedback and unpredictable rewards, it made the potentially tedious process of browsing profiles feel engaging and entertaining. However, this very success highlights the potential dangers of gamification, particularly when applied to areas involving human connection.

Floating Action Button (FAB) - ca. 2014

The Floating Action Button (FAB) is a distinct UI component, typically presented as a circular button with an icon at its center, that appears to "float" above the main interface content.It is usually anchored to a specific position, most commonly the bottom-right corner of the screen.

The Floating Action Button was introduced and popularized as a key element of Google's Material Design language, which was unveiled in 2014. It was conceived by the Google design team responsible for creating Material Design.

The FAB was presented as a core component within the Material Design guidelines and was subsequently implemented across many of Google's own flagship applications, such as Gmail, Google Calendar, and Google+, setting a strong precedent for its use. While primarily associated with Android application design due to Material Design's origins, the FAB pattern has also been adopted in web applications that adhere to Material Design principles.

The FAB's prominent placement and distinct visual style effectively draw the user's attention, clearly signaling the screen's primary intended action. Research suggests that users, particularly when encountering unfamiliar interfaces, often rely on the FAB as a navigational cue or starting point for action. Its high visibility can encourage users to perform the designated primary action more frequently. While some studies indicate a slight initial learning curve or negative usability impact upon first use, users tend to become more efficient with the FAB after successfully completing a task with it, compared to traditional toolbar buttons.

From a user experience perspective, the FAB offers the benefit of providing a clear, unambiguous, high-emphasis prompt for the most important function on a screen. Its consistent placement (usually bottom-right) aids learnability across different applications adhering to Material Design. For key tasks, it can streamline navigation and improve efficiency by making the primary action immediately accessible. As a standardised pattern within a major design system, it helps reduce users' cognitive load by providing a familiar interaction model. When used for expandable actions, the associated animations (morphing, launching) can create smooth visual transitions between states and provide contextual cues.

However, the FAB pattern also presents notable UX challenges. Its floating nature means it inevitably obstructs some portion of the underlying content, which can be problematic, especially on smaller screens. Its visual prominence, designed to attract attention, can sometimes become a distraction, detracting from the user's ability to focus on the main content, particularly in apps aiming for an immersive experience (e.g., photo viewing). A significant criticism arises when the action designated as "primary" by the designer does not align with the user's actual most frequent or important task in that context.

Key usability weaknesses include content obstruction, potential for distraction, and the risk of misidentifying the true primary user action. If the FAB expands to reveal secondary actions, the discoverability of those actions depends entirely on the user interacting with the main button.

Stories Format (ephemeral, sequential content) - 2013

The Stories format is a content-sharing pattern characterised by sequences of photos and videos that are typically displayed full-screen and disappear after a predetermined period, usually 24 hours. Users compile these sequences, often adding creative overlays like text, stickers, filters, or polls. Stories are presented separately from a user's permanent profile or feed content, offering a more transient, chronological narrative of recent moments. Navigation typically involves tapping to advance to the next piece of content within a user's story or swiping to move between different users'.

The Stories format was pioneered by Snapchat, which introduced the feature in October 2013. The Stories feature extended this concept of ephemerality to a broadcast format, allowing users to share moments with their friends for a 24-hour window. While Snapchat originated the format, its massive popularisation is largely attributed to Instagram, which launched its own nearly identical Stories feature in August 2016. This move significantly impacted the social media landscape.

Following Instagram's success, variations of the Stories format were implemented by numerous other platforms, including:

- YouTube

The format has continuously evolved, incorporating more interactive elements like polls, Q&A stickers, music, links, and advanced augmented reality (AR) filters.

The Stories format profoundly changed user sharing behavior on social media. Its ephemeral nature lowered the barrier to sharing, encouraging users to post more frequent, casual, and "in-the-moment" content without the pressure of curating a perfect, permanent feed.

The 24-hour lifespan also created a powerful sense of urgency and fueled the "Fear of Missing Out" (FOMO), driving users to check apps frequently to avoid missing temporary updates. The format encouraged passive consumption habits, with users often tapping rapidly through sequences of stories. This increased overall user engagement and time spent within platforms that adopted the format. It also heavily prioritised the creation and consumption of vertical photo and video content, optimised for mobile screens.

From a user experience perspective, Stories offer a low-pressure environment for sharing everyday experiences. They provide a chronological, narrative glimpse into others' recent activities. The format is often perceived as more authentic or less performative than highly curated permanent feeds. The integration of creative tools like filters, stickers, and interactive elements makes the format engaging and entertaining for both creators and viewers.

Conversely, the core mechanic of ephemerality is a significant source of negative UX. It is intentionally designed to leverage FOMO, which can lead to compulsive app checking and contribute to social media addiction. The constant stream of new, short-form content can be overwhelming and may negatively impact users' attention spans. The passive, rapid-fire consumption model can feel mindless or unfulfilling.