literature

The discipline of English literature seems unlikely to survive the coming technological tsunami—and maybe it doesn’t deserve to. And I say this as a professor of English, who believes in the power of the written word.

Self-portrait with book by Paul Stang (1888–1923). Stongfjorden, Norway.

Self-portrait with book by Paul Stang (1888–1923). Stongfjorden, Norway.

Reports show that enrolments in English Literature majors have been declining for some time. Enrolment in my own department has declined some fifty percent since I was hired in 2007. People have variously ascribed this to changing demographics or economic concerns, or to the fact that many English departments have become leftist propaganda outlets. I’m apt to support the latter charge—but it’s not even evil right-wingers out for revenge who are going to deal the death blow to English Departments. It’s AI.

When ChatGPT can analyse Hamlet as well as any grad student, we might reasonably ask, “What is the point of writing papers on Hamlet?” Literary analysis, after all, is not like building houses, feeding people, or practising medicine. Even compared to its sister disciplines in the humanities (e.g., history or philosophy) the study of literature serves little practical need. And, besides, when machines can build houses as easily as people, we won’t need people to build houses either.

So, why do we teach English literature (or “language arts,” as some secondary schools now call it) at all? According to the nineteenth-century British literary critic Mathew Arnold, the purpose of studying and teaching literature is “to know the best that is known and thought in the world, and by in its turn making this known, to create a current of true and fresh ideas.” In Arnold’s day, people had a pretty good idea of what was “the best that is known and thought”: it was Homer, Sophocles, Virgil, and The Bible, alongside vernacular works by greats like William Shakespeare, John Milton, and William Wordsworth. Writers like Thomas Hardy, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf were later added.

There were debates here and there about who or what was the best work or the greatest author. Was William Blake a genius or a nutcase? Was Charles Dickens serious literature or sentimental claptrap? The so-called “canon” of great literature was open for debate and ever evolving. But greatness itself was not in question nor was the reason for reading. We read to make ourselves better people—deeper thinkers with a greater understanding of humanity, people who were more empathetic, people capable of critical thinking. English literature was, in truth, a substitute for religion. We wanted people to be good, but we no longer believed in God. Instead, we believed in Shakespeare, Milton, and eventually Toni Morrison. Until we didn’t.

It’s always been problematic, though, this idea that literature makes you a better person. Besides the obvious counterfactuals—the allied soldiers allegedly found copies of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s works in the desk drawers of Nazi prison guards when they liberated the camps—there were the problems that always arise when you try to push your religion on other people.

Our religion was literature, and like any people of true faith, we deeply believed in it, thought it was essential, thought everyone must be saved through it. The remarkable thing was that we somehow convinced American college presidents of the idea, but then again, many of them, like University of Chicago president Robert Hutchins, creator of the “Common Core” and advocate of “Great Books,” were members of the same religion. Not all countries make students of mathematics and engineering take literature courses, but in the United States we do. So for nearly a century, we evangelised our religion to college students, some of whom were already in love with reading and therefore happy to worship at the Temple of Literature. Many were not, but, nonetheless, we rammed Shakespeare, Herman Melville, and Toni Morrison down their throats—to make them better people.

That doesn’t mean that it necessarily stayed with them. In Hungary, before the fall of communism, Russian was compulsory in all schools. Yet many Hungarians of that generation stubbornly refused to learn the language and cannot speak it today. Likewise, even if you force a person to read Hamlet, you have no way of making him retain anything meaningful after the test date. Some students of the right temperament and with the right intellectual predilections are drawn to the Temple of Literature, but most are not. For most, it is like going to Sunday school—they endure it reluctantly and quickly forget any lessons learned.

On the Study of Great Books

Great books require intelligence and judgment, and the exploration of sometimes quite fundamental disagreement, from the outset.

In the 1960s and 70s, about a century after Arnold wrote “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time,” the canon was expanded to encompass a wider range of writers, including more women and people of colour. This meant that, if you were a progressive, you could go on worshipping literature and still feel good about doing so—even if some feminists and Marxists would tell you that D.H. Lawrence and Ernest Hemingway were misogynists. But the mainstreaming of deconstruction, postmodernism, poststructuralism, and their ilk in the 1980s spelled the beginning of the end, as they tore down the spiritual/religious underpinnings of English as a discipline. There was no rescuing the canon through expansion. The whole thing had to go because “the best that is known and thought,” it was alleged, was just code for whatever keeps powerful white men in power.

Next, literature was demoted to “text.” There wasn’t anything special about, say, Moby Dick. You could read it like you read the label on the back of a soup can—or vice versa. You could read the back of a soup can as a text no less interesting than Melville’s novel. You didn’t read to learn something from the “great authors.” Not only were there no great authors; according to Roland Barthes, no authors of any kind existed anymore. You read to learn skills in analysis and deconstruction—that being the art of demonstrating that what you are reading doesn’t actually say what people, including the author, think it says, but something quite different, often radically contradictory to the apparent meaning. And you read to learn how to critique—i.e., attack—the cultural legitimacy of the text and of culture itself.

This is when English departments turned into greenhouses for growing leftists, which is why many conservatives are so gleeful about their decline. But, to be fair, English departments have always been ideological. English professors were first priests of culture and then, after the postmodernists turned everything upside down, became anti-priests of culture, evangelists not of art but of dismantling texts in order to fight the system. In either case, the average kid coming into an English class—unless he or she was a true believer—was, yet again, subject to a glorified Sunday school and forced to learn the catechism. Most didn’t learn about either literature or text, but only how to get by or to get over on their teachers. They got over on us by cheating, by copying answers, by getting other students to write their papers, by plagiarising. Now they get over on us by using AI.

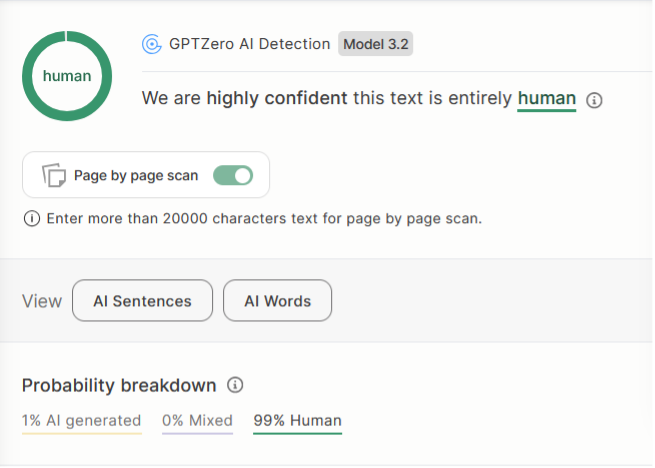

Up until now, teachers still had the power to make students read books and write essays on them. A few cheated—but the ones most likely to cheat were generally the ones least likely to know how to get away with it, so many cheaters were detected. But now you no longer have to copy or plagiarise or buy someone else’s work. AI will write your paper or take your exam, and its language will be too unique to pin on anyone else. There are still some tell-tale signs of AI generation, but the algorithms are getting better at writing convincingly human-sounding prose by the day.

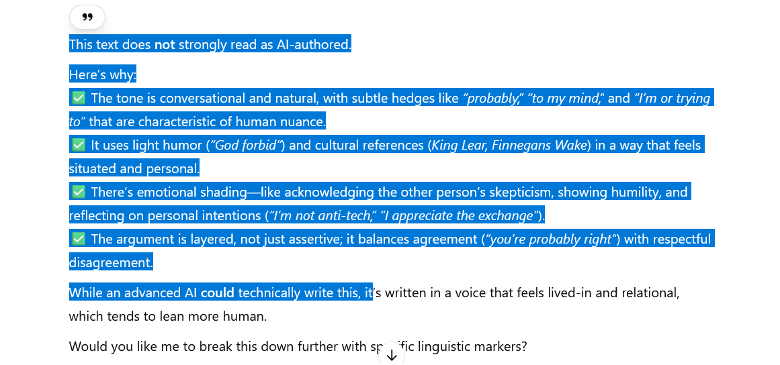

I had recently had a debate on Substack with a software engineer who claimed that “the undetectable level [of AI writing] will not be reached for some time.” I asked ChatGPT to respond to him, directing it to write like me, using contractions, conversational style, and even typos. My AI expert did not recognise that he was engaging with an AI. I then had ChatGPT itself check the responses it had generated, and it told me that those responses had clearly not been written by AI. ChatGPT failed a self-administered Turing Test.

My Friend the Chatbot

Virtual friends are already good enough to engage us and satisfy some of our appetites. They are going to get better, spread into more corners of our lives, and settle in.

ChatGPT did a remarkable job of impersonating my style. Here’s what it wrote:

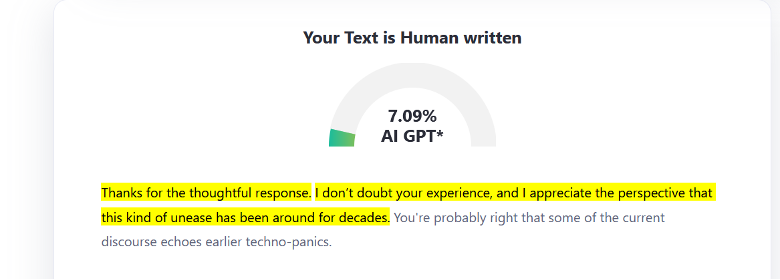

Thanks for the thoughtful response. I don’t doubt your experience, and I appreciate the perspective that this kind of unease has been around for decades. You’re probably right that some of the current discourse echoes earlier techno-panics. That said, I don’t think it’s a “handwave” to suggest that reading texts written by actual human minds cultivates certain habits better than machine-generated ones do—at least not yet. I’m not claiming literature is the only path to empathy or nuance, but it’s a pretty time-tested one. There’s a reason we still teach King Lear, not just plot summaries of King Lear. And while I’m definitely not assigning Finnegans Wake (God forbid), I do think part of the value in reading hard things is that they’re hard. Learning to sit with confusion and still find meaning is, to my mind, part of becoming a deeper reader—and maybe a better person. I also hear your skepticism about teaching empathy. I don’t think of it as moral instruction, exactly. More like exposure. A good story doesn’t tell you what to feel; it just gives you a chance to feel something from the inside out. That’s hard to replicate in a bullet-point summary. As for leaning in: I am, or trying to. I’m not anti-tech, and I’m not trying to protect some fragile literary past. I just think we’re at a point where we need to be a little more deliberate about what we hand over. Especially when the tools we’re using start to sound uncannily like us. Anyway, I appreciate the exchange. You’ve given me a lot to think about.Afterwards, when I asked ChatGPT if the text above had been written by an AI, it responded:

Just to be sure, I tried two other AI detectors, which gave me the following results:

We can still get around the problem by requiring students to handwrite essays in class. But then we will also have to prohibit the use of mobile phones—no easy task—and that solution won’t work once wearable tech becomes more sophisticated. Eventually, you won’t need your phone: you’ll be able to use your glasses or a watch or a ring or an implant. How will we be able to prevent our students from asking AI to write their papers when the AI chip is implanted behind their eyeballs? That will surely be game over. We might be able to convince a few true believers to play along with the religion of either literature or text, but most will not, and we Sunday school teachers will be out of business. But maybe we shouldn’t have been in business to begin with. What business did we ever have insisting that everyone needs to read Shakespeare just because we found it meaningful and enlightening?

.png)