“Everywhere, everything is ordered to stand by, to be immediately at hand, indeed to stand there just so that it may be on call for further ordering.”

— Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology

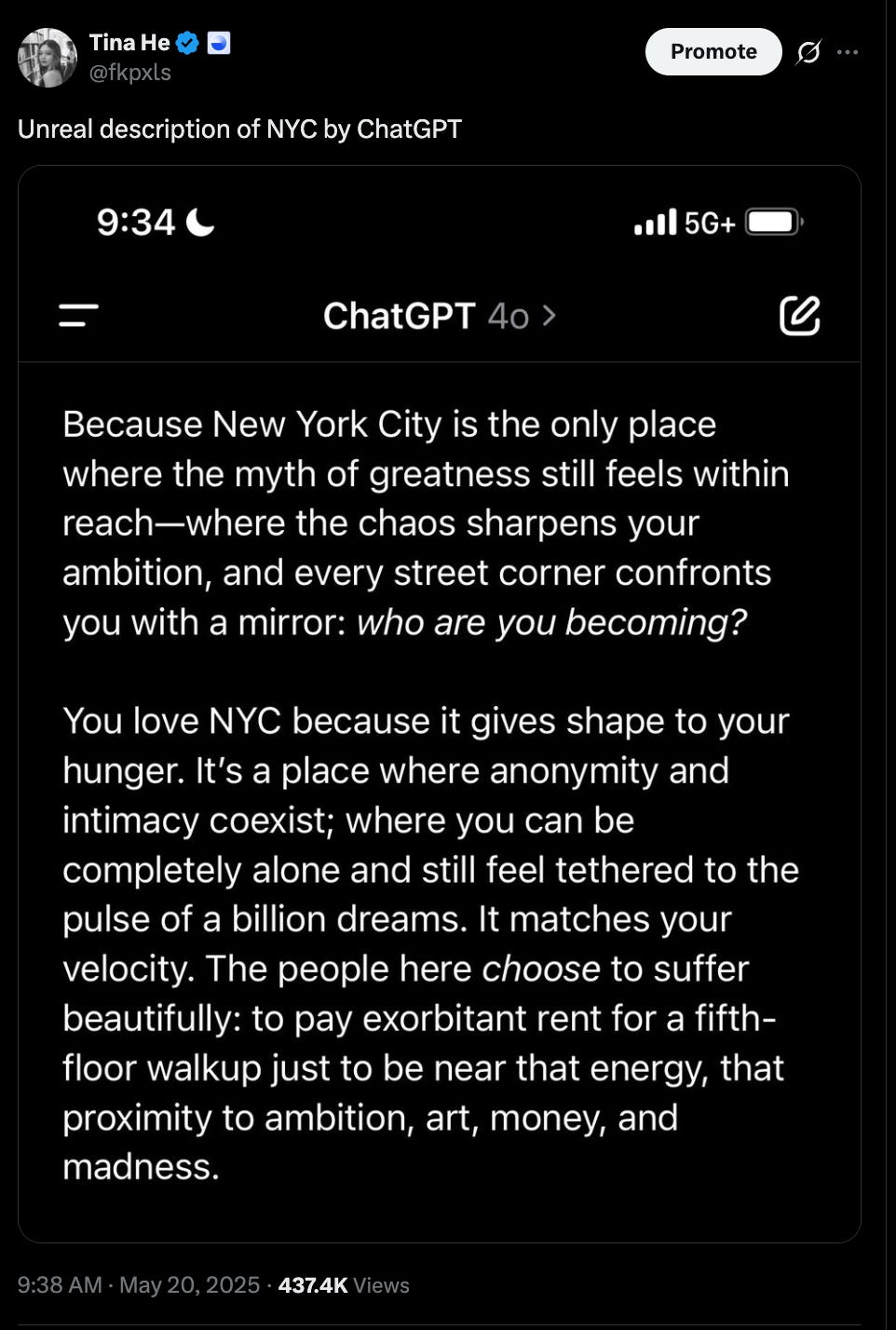

Earlier this week, I posted a screenshot of ChatGPT’s take on life in NYC, a response so oddly specific and human that I couldn’t resist sharing it on X.

It spread far wider than I’d anticipated. While most people found the AI’s description uncannily relatable, what also surfaced were waves of revulsion and disbelief. For many, the exchange seemed to distill everything shallow, culturally tone-deaf, and myopic about our tech-infused world, laying bare a kind of algorithmic emptiness that unsettled far beyond the intended, lighthearted message.

But what exactly provokes this visceral backlash (as well as resonance)? It’s not the simple fact that a machine is writing, but the feeling that machine-generated content can mimic the outward signs of expression while lacking the inward spark.

Unlike obvious automation in spreadsheets or homework grading, which we view as mechanical drudgery and are happy to offload, AI-generated prose attempts to inhabit domains we instinctively associate with authentic subjectivity: observation, memory, yearning, regret. When an LLM “describes the rain” or tries to evoke loneliness at a traffic light, it produces language that looks like the real thing but does not originate in lived experience.

This is more than a question of quality or taste; it’s a deep uncertainty about agency, intent, and presence. Readers detect a “hollow center” in the prose, a structure of feeling without anyone actually doing the feeling. Is the AI’s sketch of New York a cultural artifact, or just a mirror reflecting back our own data trails? The more the form resembles genuine expression, the more disturbing its lack of personal context becomes.

Psychologists and critics (see Sherry Turkle’s work on simulation, or Byung-Chul Han on transparency) suggest that humans crave the recognition of another mind behind communication. The anxiety isn’t about replacement per se, but about a new “algorithmic uncanny valley”: content that teases meaning but never fully arrives at it, leaving us unsettled not because the machine “gets it wrong,” but because there’s no one there to get it at all.

Why is that?

To understand this discomfort, we need to examine what makes AI fundamentally different from traditional technology. The philosophical core, I believe, is not that "AI is evil" in the classical sense—calculated harm, malice, or sadistic pleasure. Quite the opposite. What unsettles us is AI's supreme indifference, or commonly called "slop," which is also synonymous with the lacking of soul.

Software doesn’t hate, plot, or hold a grudge. It optimizes. That optimization, crucially, includes the effectiveness of language—words as system output, not as evidence of intent. This is where Hannah Arendt’s insight on the “banality of evil” feels uncannily relevant. In her words:

“The essence of totalitarian government, and perhaps the nature of every bureaucracy, is to make functionaries and mere cogs in the administrative machine out of men, and thus to dehumanize them.”

“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

(Eichmann in Jerusalem)

Arendt warned that true horror is not always orchestrated by monsters, but by “nobodies” who “never realized what they were doing,” turning the crank on the machine, unthinking and unfeeling. It is not the bloody hands of the tyrant at the levers, but the process itself that advances, absent of intention. “In place of intention, we get process.” The algorithm does not conspire; it just runs.

Humans hunger for narrative, for intent lurking behind the curtain—heroes and villains. In the church of the algorithm, we encounter an abyss: “There is no one there.” That absence suffocates us more than the prospect of a plotting demon. We want our villains to mean what they do; we are lost before an unfeeling God.

Lila Shroff’s luminous speculative fiction was incredibly prescient in foreseeing how the compression of human communication could lead to tragic outcomes in the name of efficiency. The protagonists, Kate and Hannah, best friends from college, had a falling out due to the installation of an AI summary app in Hannah’s email inbox, which failed to pick up the emotional distress and depressive symptoms of Kate.

Our brains, evolved for tribal politics and campfire stories, are ill-equipped for the moral ambiguity of a system with no soul to save or damn.

Our discomfort with this indifference manifests in a predictable pattern: we try to turn AI into a comprehensible villain. In reference to Girard, every society is built, in part, on the ritual of scapegoating, a mechanism by which collective anxieties, rivalries, and fears are projected onto a villain or outcast, thereby restoring temporary order through exclusion or blame. We yearn for something or someone to hold accountable, a focal point for our moral clarity and rage. Today’s technology is a perfect canvas for those projections.

The terror is existential. AI shakes the stories we tell about our uniqueness—our creative spark and our sense of agency. Western moral philosophy, from Kant to Nussbaum, revolves around treating humans as ends in themselves, never just means. To reduce a person to a function isn’t just a philosophical error, it cuts at the heart of our dignity.

And yet, the logic of AI, especially as business infrastructure, makes this reduction feel inevitable. Algorithms sort us by engagement scores, by revenue-per-user, by “propensity to churn.” The most controversial AI applications—social credit systems, predictive policing, “optimized” hiring—aren’t dystopian because they are cruel, but because they are perfectly indifferent.

What if this tendency to villainize AI obscures a deeper truth about how technology reshapes not just our tools, but our entire way of seeing the world?

Long before AI, philosopher Martin Heidegger anticipated this transformation.

In The Question Concerning Technology, Martin Heidegger warned that technology is not just a collection of tools, but a way of seeing the world, a revealing that both illuminates and conceals. Heidegger’s “enframing” (Gestell) describes technology’s insidious power to frame everything (nature, humans, even time) as “standing reserves,” ready to be ordered, manipulated, consumed.

“Everywhere everything is ordered to stand by, to be immediately at hand, indeed to stand there just so that it may be on call for further ordering.”

In this view, AI is not merely software deployed for business efficiency. It is a force that recasts reality itself through the lens of optimization, availability, and control. The data labelers, the Uber driver, and even the AI-augmented knowledge worker, anyone below the LLM all at some point become “resources” in a perpetual state of readiness.

But Heidegger wasn’t a Luddite. He saw a paradox: technology both reveals and conceals. It produces astonishing new worlds, but only by flattening the world into what can be stored, indexed, and summoned at will. In the digital age, this is literal. Every social act, every click or hesitation, becomes a data point, a potential input to someone’s model.

In the workplace, to be called a “machine” is, weirdly, a compliment: a tribute to one’s measurable output, reliability, and consistency. Productivity software rewards us for becoming more like the systems we build: efficient, predictable, and always on.

But as soon as AI demonstrates even a flicker of poetic intent, a gesture toward the unquantifiable—art, longing, vulnerability—many repulse. Some do so because they sense (correctly) that computers are still not good at this; others, because they sense that it is only a matter of time. Both reactions betray a fear that the territory of the soul, of human meaning, is shrinking. The room for contemplation, leisure, and error is increasingly defined by what resists digitization, until, suddenly, even error is modeled.

AI systems present themselves as agents of transparency, optimization, ranking, and matching with a supposed objectivity. But their inner workings, from transformer weights to diffusion mechanisms, are often profoundly opaque. Even the researchers behind the models struggle to explain why certain outputs appear, why some biases manifest, or how adversarial data alters meaning. This opacity is not just technical, but philosophical, a concealment at the core of the digital order.

Efforts at “interpretable AI,” “explainability,” or algorithmic audits echo Heidegger’s call toward aletheia, the ancient Greek notion of unconcealment, or truth-as-revealing. The contemporary push for AI transparency is, at its best, an effort to reclaim dignity and agency within systems that profit by rendering us invisible to ourselves.

The contemporary push for AI transparency is, at its best, a bid to reclaim dignity and agency within systems that profit by making us invisible to ourselves. But even this may not be enough to address the existential challenge AI poses.

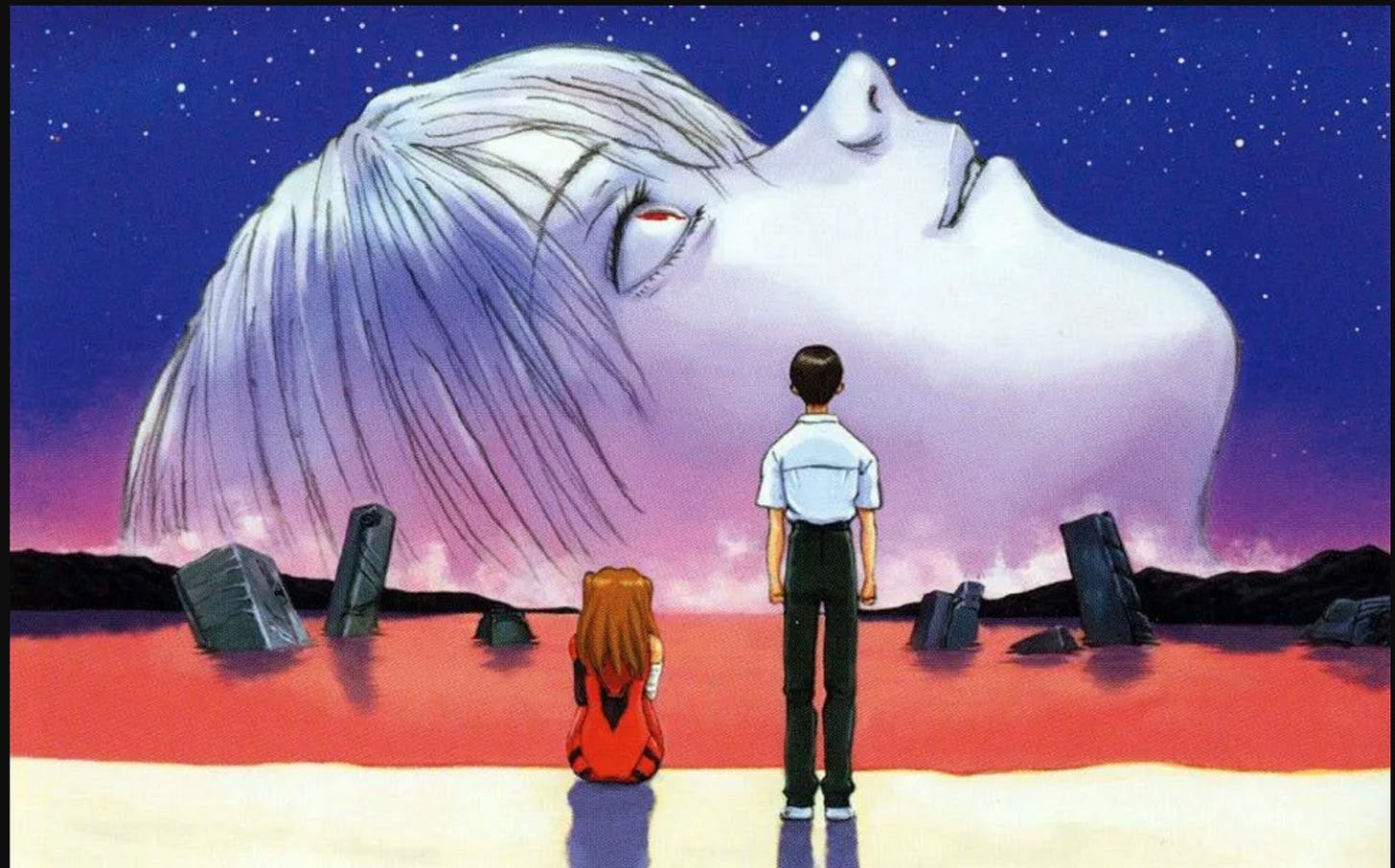

"Any where can be paradise, as long as you have the will to live, after all you are alive, you will always have the chance to be happy. As long as the sun, the moon, and the Earth exist, everything will be alright." — Yui Ikari from Evangelion

In Neon Genesis Evangelion, the “Human Instrumentality Project” offers to dissolve all suffering through perfect togetherness. No more pain, no more loneliness, every fragment of individual consciousness merged into a single, undivided mind. It is paradise, and it is annihilation.

Evangelion’s answer is ambiguous. The protagonist, Shinji, and his shattered friends are offered relief from their existential ache, but at the price of agency, individuation, and the possibility of meaning. The show is a fever dream of depressive suffering and the refusal to submit to a world without boundaries, without the dignity of suffering one’s own fate.

What makes us human is not the absence of pain, but the experience of it as ours. AI, in its idealized form, offers collective agency, a solution to loneliness, an optimization of every choice. But as both Heidegger and Evangelion warn, the cost may be unbearable: the flattening of selves into a seamless, computation-ready mesh.

Evangelion's ambiguous ending, neither full acceptance nor total rejection of instrumentality, points us toward a more nuanced response to our technological moment.

This brings us back to Heidegger, who offers a paradoxical hope.

Yet, as Heidegger’s essay also insists, the very force that threatens us may harbor its own “saving power.” Recognition of technology’s danger is itself a call to awaken.

But he doesn’t ask us to simply retreat, become luddites, or declare defeat in the face of technocratic sprawl. Instead, Heidegger compels us to do something much harder: to see the world as it is being reframed by technology, and then to consciously reclaim or reweave the strands of meaning that risk being flattened.

The “saving power” arrives not as a counterweight, but as a paradox: we are awakened to the danger precisely through contact with it. The same algorithmic indifference that unsettles us may also jolt us into a higher vigilance, a refusal to hand over the entirety of our experience to optimization, market logic, or digital control. The very anxiety these systems produce is a clue: something vital, unquantifiable, and irreducibly human still resists.

This isn’t about throwing away the tools, but about wrestling them into alignment with what we find sacred or essential. We won’t find salvation by escaping technology, but by using our awareness—our capacity for critique, ritual, invention, and refusal—to carve out room for messiness, for mourning, for risk, and for deep attention. The saving power is the act of remembering, in the heat of technical progress, to ask: “What space remains for meaning? For art? For wildness, chance, suffering, and genuine encounter?

AI is not inevitable fate. It is an invitation to wake up. The work is to keep dragging what is singular, poetic, and profoundly alive back into focus, despite all pressures to automate it away.

What unsettles us about AI is not malice, but the vacuum where intention should be. When it tries to write poetry or mimic human tenderness, our collective recoil is less about revulsion and more a last stand, staking a claim on experience, contradiction, and ache as non-negotiably ours.

But perhaps that defensiveness, too, is a signpost. What if the dignity of being human is not to stand forever outside the machine, but to insist, even as the boundaries blur, on those things that remain untranslatable—mess, longing, grief, awe, strangeness? What if technocracy and romantic withdrawal are not our only options, but two poles of a far richer field, a frontier where we move, trade, shudder, and insist on meaning?

Call it “the saving power,” call it “instrumentality,” call it the refusal to become seamless. Our task is not to panic when the machine gets close, nor to mythologize our differences into oblivion, but to take seriously the ongoing work of being human: suffering, loving, resisting reduction, and making art out of what refuses to compute.

That, for now, is enough. Maybe the challenge is to keep returning to these questions—not to solve them, but to stay alive inside them.

Heidegger, Martin. “The Question Concerning Technology”

Arendt, Hannah. “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil”

Nussbaum, Martha. “The Fragility of Goodness”

Neon Genesis Evangelion (Anime), Hideaki Anno, 1995

On interpretability and AI transparency: Doshi-Velez & Kim, “Towards a Rigorous Science of Interpretable Machine Learning”

On the loss of dignity: Michael Sandel, “What Money Can’t Buy”

On the human instrumentality problem: Robert Nozick, “The Experience Machine”

.png)