In 2002, a dentist in Oregon named Jordan Sparks felt so dissatisfied with cryonics, he decided to start his own organization.

This would not be a trivial matter. Funding it, finding sane and reliable staff who would share a commitment to the concept, signing up members, doing arduous standby-transport work, resolving legalities, acquiring all the necessary equipment—was Dr. Sparks seriously planning to pursue this on his own, without any prior experience?

He announced his intention on a mailing list named CryoNet. The list was notorious in those days for bad-mannered squabbling, and sure enough, the participants mocked his ambitions. One person even dismissed Sparks as “ill informed” and “clueless.”

What no one realized was that he had a remarkable aptitude for computer programming. He knew that dentists needed software for many aspects of their practices, so he started writing it and selling it to them, and this enterprise became so successful, he stopped doing dentistry.

His software company, named Open Dental, now employs 440 people and has enabled him to fulfill his seemingly far-fetched ambition. In 2024 he completed construction of a new building in which to preserve patients and pursue research. It cost him $7 million and contains almost 20,000 square feet, a space equivalent to four basketball courts.

Initially he named his organization Oregon Cryonics, but changed it to Oregon Brain Preservation as he decided to deal only with the human brain. More recently, the enterprise became Sparks Brain Preservation, as its ambitions have expanded beyond its location in Salem, Oregon. In this text, I will refer to it as SBP.

Sparks also established a research entity named Apex Neuroscience, which is why that logo appears at the corner of his big, square building in Figure 1. Apex is a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization that hopes to receive donations facilitating brain preservation research.

SBP is a nonprofit mutual benefit organization (not tax exempt). Currently it has 41 members, 20 patient brains preserved, and 11 pet animals (an additional one was transferred to Alcor Foundation). Five of the human patients and two of the pets are in liquid nitrogen, as they predated the current protocol.

Figure 1. Sparks Brain Preservation shares this building with Apex Neuroscience, both entities created by Jordan Sparks, DMD.

For many decades, cryonics organizations have relied upon one basic principle to achieve tissue preservation: They have reduced the patient’s temperature. According to the Arrhenius Equation (which is easily found online, if you are curious about it), all chemical reactions occur more slowly at lower temperatures. Since liquid nitrogen is cheaply available as an industrial byproduct, and is delivered at –196 degrees Celsius, it seems ideal for the task. No refrigeration is required; just insulated containers.

SBP does things very differently. Unlike other organizations, it arrests biological processes by chemical fixation, which can occur above the freezing point of water. When the fixation process is complete, patients can be stored indefinitely at –20 degrees Celsius, after a graded immersion in cryoprotectants considered sufficient to prevent freezing.

Formaldehyde is the preservative of choice, with the addition of glutaraldehyde when perfusion can be performed with minimal delay after legal death. More details are readily available at the SBP web site:

https://sparksbrain.org/ourPreservationApproach.html

The advantage of chemical fixation is that it enables a pristine quality of preservation, while preventing two types of damage that have plagued cryobiology ever since the 1950s:

Damage caused by freezing,

Damage caused by toxicity caused by cryoprotectants that are intended to prevent damage caused by freezing.

Chemical fixation has biological consequences of its own, but its best-known disadvantage is that it is not reversible. On the other hand, using techniques available today, cryopreservation is not reversible, either. No mammal has ever been revived after storage at a temperature low enough to insure indefinite preservation. As every cryonicist knows, you’ll need clever molecular machines to repair microscopic debris and fill voids in brains of patients who receive imperfect cryopreservation.

Well, then: If some kind of uber-technology will be required, why not minimize brain damage in the first place by using the simpler process of chemical fixation? Robert J. Freitas, Jr. has mentioned the possibility of undoing the changes caused by fixation on a molecular level in his book Cryostasis Revival, but a more popular scenario among fixationists involves scanning the brain and rebuilding it, either in the physical world or as pure data.

This has been discussed in cryonics since at least the 1980s, but has always been controversial. Startups such as Nectome have pursued fixation on a research basis, but Jordan Sparks is the first person to offer it to members of an organization as the default option for preserving the brain.

Sometimes I wonder if fixation has been stigmatized by the knowledge that morticians use formaldehyde. But there is another issue: If a copy of a brain is made in the future, will it be functionally indistinguishable from the brain itself? This question has led to debates about “identity,” a word which I find troublesome, because it has a circular definition: It was invented by humans to describe themselves.

Since the identity debate cannot be resolved at this time, I won’t deal with it any further in this text. The tempting aspect of chemical fixation is that it can achieve very impressive results with minimal complexity and low subsequent maintenance costs.

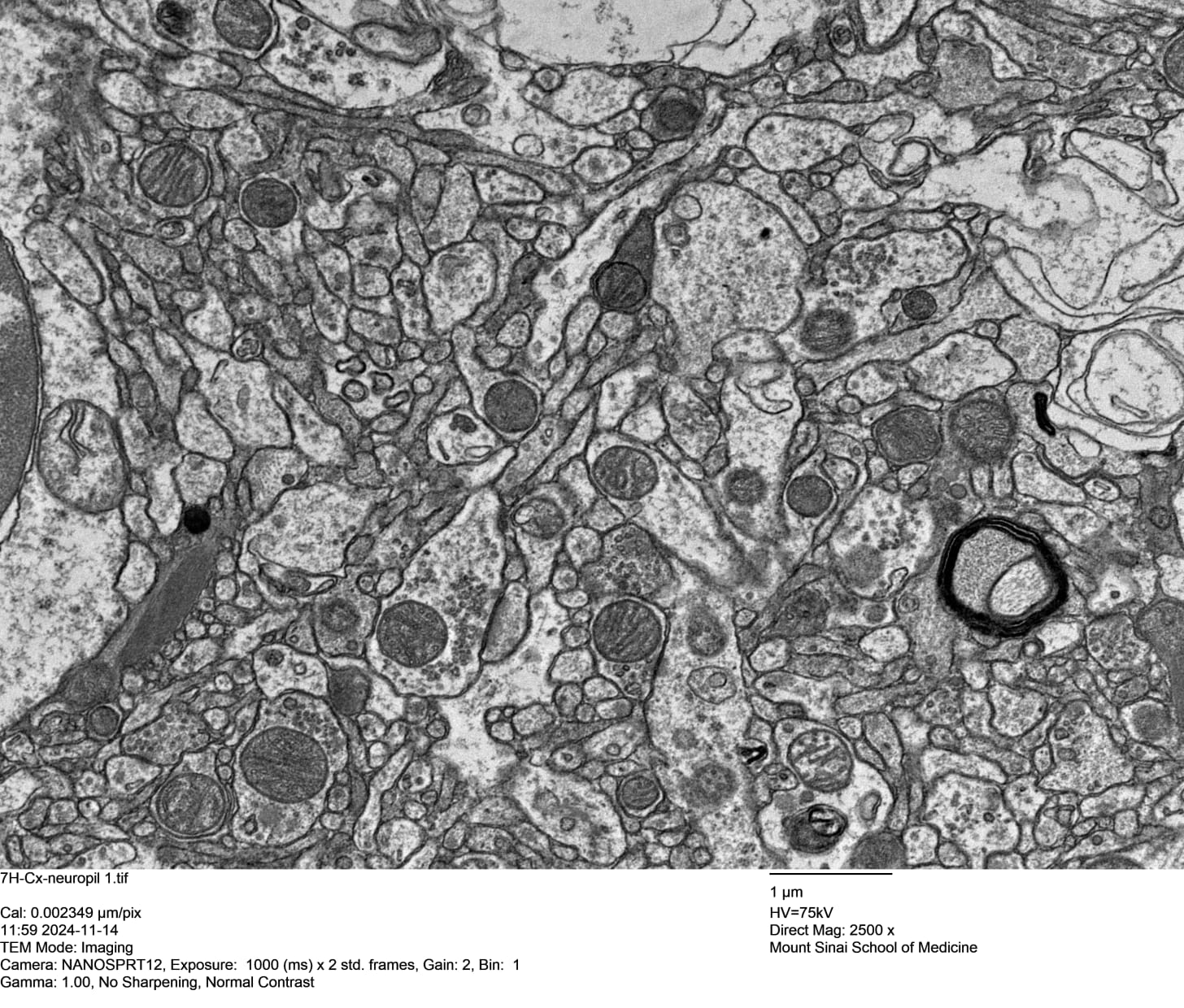

An example of a human brain sample preserved by fixation is shown in Figure 2. This image is from a donated human brain, preserved at SBP with current methods, after 4.5 hours of warm ischemia. The image was saved at approximately 4,000 x 3,000 pixels resolution but when you view it here, probably it will have been downsampled by Substack. It appeared originally in a paper archived by the National Library of Medicine at

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40567433/

Figure 2. Sample of a human brain perfused with aldehyde.

If fixation is applied more promptly, it can lead to even better ultrastructural preservation quality. But if a significant delay occurs, this does not necessarily mean that a case will be refused. “We’re not saying that the quality is good in delayed cases,” Jordan Sparks comments, “just that it’s always better than with cryopreservation.”

Bearing all this in mind, if you wish to defy death, you now have two options:

You can risk losing significant brain structure during the imperfectly applied process of cryopreservation, while hoping that nanosystems will infer what isn’t there anymore, and reconstruct it, so that you can be revived as you once were. Or,

You can get probably excellent but nonreversible structural preservation by using chemical fixation, while perhaps hoping that the brain can be scanned and replicated one day, to create an entity that is indistinguishable from “you.”

Opting for (1) or (2) may be a philosophical preference.

Personally, I tend to believe that humanity will abandon the physical realm and go “100% virtual” when sufficient computing power is available. The virtual realm eliminates most penalties imposed by the physical world, such as disease, pain, and mortality—assuming that ongoing maintenance by robots will support the necessary hardware. So why settle for less?

I admit that I have a long-standing bias, as I wrote about copying the brain into a virtual environment in my novel The Silicon Man, published in 1991. It was inspired partly by Mind Children, a nonfiction book by roboticist Hans Moravec, which explored arguments in favor of uploading the brain much more thoroughly than I can. Anyone interested in this topic will find a lot of questions answered in Mind Children.

The debate between cryonicists and fixationists recently became somewhat more intense when Jordan Sparks denounced cryonics as being “unethical.” In May, 2025, on a web-based discussion list that he maintains, he wrote:

I’ve decided that offering cryonics is unethical, whereas offering aldehyde brain preservation is not. I did not arrive at this position quickly or carelessly. It took 30 years of very gradually changing my mind. I accepted aldehyde as reasonable about 20 years ago. . . . I accepted aldehyde as superior about 6 months ago, and then yesterday I finally understood that offering cryonics is unethical. . . .

1. Aldehyde quality is better

2. Aldehyde preservation is evidence-based

3. Cryonics is, by contrast, experimental

4. Cryonics is not research

5. Cryonics is not benign

It’s not ethical to offer experimental procedures for patients. They should only be getting evidence-based care. It’s really that simple.

(This is an abridged summary of his statement. The full text is at https://oregonbp.com/cryonicsVsAldehyde.html.)

Regardless of how you feel about this, I do find it refreshing to see someone raising ethical issues in conjunction with strategies to defeat mortality. If there have been any ethical discussions in statements from Alcor Foundation, Cryonics Institute, or Tomorrow Bio, I don’t recall seeing them recently.

The prospect of reconstituting a person from a brain scan may seem highly speculative, but within the current constraints of technology, the approach of SBP is rooted in the scientific method. By gaining access to 156 human brains as anatomical donations since January, 2024, SBP has done something that no cryonics organization has ever achieved or even attempted, so far as I am aware. It has practiced its procedures repeatedly on whole human brains, and evaluated them with a CT scanner and an electron microscope before tweaking the procedures slightly, trying again, and comparing the results. This is what experimental science is all about: Try option A, and evaluate. Try option B, and compare. Try option C—and so on.

Alcor Foundation has its own CT scanner which uses false color to compare areas of a cryopreserved brain that are relatively well or relatively poorly vitrified. However, the scans are in relatively low resolution, and since the cryopreservation of human patients involves many variables, modifying procedures in response to CT data is problematic.

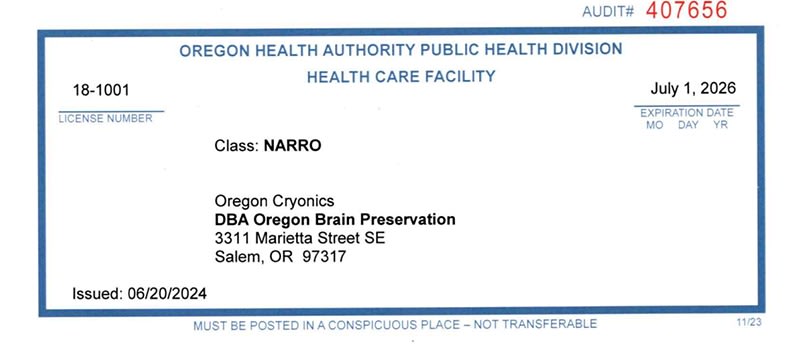

The State of Oregon has licensed SBP as a Nontransplant Anatomical Research Recovery Organization (NARRO), and the certificate is shown in Figure 3. This license affirms the right to accept body and tissue donations under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act.

Figure 3. This certificate confirms that Oregon Cryonics (subsequently renamed Sparks Brain Preservation) has official status as a Nontransplant Anatomical Research Recovery Organization in Salem, Oregon.

A major advantage of SBP being located in Oregon is that if you are suffering from a terminal condition, you can go there and receive medical assistance in dying (often abbreviated as MAID), enabling immediate, optimal preservation. Many other states allow MAID, but Oregon and Vermont are the only ones currently permitting the procedure for nonresidents.

MAID in Oregon faced powerful opposition from special-interest groups. Legislation to enable it failed three times during 1989 through 1993. Finally a ballot measure passed with 51% approval in 1994, and after legal challenges were rejected by the Supreme Court of the United States, the first prescriptions to enable assisted suicide were issued during 1998. In 2023, the law was modified to accept non-residents of the state, and in 2025, the 15-day waiting period that was required previously was reduced to 48 hours. At this point, if you are suffering a terminal condition, and you can obtain the necessary documents from a doctor in Oregon, your chances of receiving MAID appear to be good.

SBP must use an outside provider to administer the actual procedure, but it can be performed in a room in the Apex facility. After death is pronounced, the operating room is adjacent. I am not aware of any cryonics organization in the United States that has this end-of-life capability in its own facility.

Of course, if you die unexpectedly, MAID is of no use to you. Preservation procedures have always been of doubtful value in cases of sudden or unnatural death.

In September, 2025 I went to Oregon and met Andrew McKenzie, the research scientist at SBP, who has an impressive array of framed diplomas on the wall of his office. He received an MD and PhD from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai hospital in New York City. His PhD was technically in genetics and genomics, but his initial coursework was in neuroscience, and he passed the qualification exam for neuroscience. His research was on the molecular neuroscience of Alzheimer’s disease.

Although Andrew was formerly a member of Cryonics Institute, he is now a hardcore advocate of chemical fixation. “It’s better structural preservation,” he says, “and it’s cheaper, and more secure.”

Approximately half of the Apex building has been developed so far. Figure 4 shows the operating room with table, CT scanner, and additional equipment used for brain preservation. Figure 5 is laboratory space, including a fume hood. Figure 6 is the sterilization and cleaning room, also containing Pelican containers to transport equipment for remote cases. Figure 7 is the instrument cleaning room. Figure 8 is the vehicle parking bay.

Figure 4. The operating room.

Figure 5. Laboratory space.

Figure 6. Sterilizing and cleaning room, with equipment for remote cases.

Figure 7. Instrument cleaning room.

Figure 8. Vehicle parking bay.

Figure 9 shows a walk-in refrigerated room storing whole human brains that were donated for research and are now preserved in aldehydes for reference purposes.

The patients who have been preserved in anticipation of revival at some time in the distant future are stored in a separate vault with steel access doors, shown in Figure 10. A refrigerator inside the vault is visible in Figure 11.

Figure 9. Brains donated for research, stored in this refrigerated room.

Figure 10. Doors to the vault.

Figure 11. Patient brains in the storage vault, on their long journey to the future, seeking biological revival or scanning for replication in physical or virtual form.

SBP is planning to store patients at –20 degrees Celsius, but before using this method, which is common in conventional neuroscience research, the organization wants to run samples through their cryoprotectant ramp up/down protocol, to verify that no changes occur at the ultrastructural level compared with samples that are not processed through this protocol.

When storage at –20 degrees begins, Andrew is quick to emphasize that no freezing will occur. “We add cryoprotectant in such a way that we get 100% penetration. We get visual confirmation of this on the CT scanner, so we know it’s 100%. We never have to worry about ice crystals.”

However, conventional cryopreservation at cryonics organizations requires no refrigeration. What if the refrigeration equipment at SBP malfunctions?

“Temperature fluctuations won’t change the physical status of the brain,” Andrew claims.

Since chemical fixation followed by storage at a mere –20 degrees allows the perfusate to remain in a perpetually liquid state, how long will brain structure last?

Andrew’s reply: “It’s probably good for centuries. But nobody really knows for sure. We don’t see any changes in the brains we have stored so far, but there are theoretical changes on a chemical level over very long periods. There could be some oxidation, or a small portion of the proteins might get broken down.”

Currently membership in SBP is $150 per year, and the procedure can be available at no cost at all if you are within 250 miles from the facility and satisfy certain conditions. Costs increase if you require a more remote standby and retrieval, depending on the number of time zones separating you from Pacific time. Three vehicles are currently undergoing conversion for remote cases.

The fee schedule for SBP is at

https://sparksbrain.org/services.html.

SBP seems to believe that by charging as little as possible, they will attract as many people as possible. “I think it’s ethical to preserve as many people as we can,” Andrew comments. “And doing cases is useful to us, because we get more practice.”

Personally I speculate that the low fee schedule could tempt some cryonicists to acquire “dual cryo-citizenship.” SBP could be added as a backup to existing, conventional cryonics arrangements. I don’t think any organization currently prohibits a member from having additional arrangements elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Andrew emphasizes that the highest priority is research, and the large empty areas of the building should be occupied eventually by researchers and lab equipment. “We’re not yet at the level of structural preservation that is ideal,” he explains. “There are a few ways in which we can get better. We’re trying different chemicals in the perfusion mix, in addition to formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde, to see if that will improve the perfusion. But additives can cause other problems. Polyethylene glycol improves the quality, but it causes dehydration, and we have to balance better perfusion with dehydration damage.”

What about digitizing the brain? When would that occur?

“Performing the scanning would not be done until the revival process is beginning. The scanning technology is going to keep getting better and cheaper, over time, and is likely to be destructive, so you don’t want to do it until you know your technology is good enough.”

Another delaying factor may be regulation. “When you have life-and-death issues,” Andrew comments, “you may not be interested in the State, but the State is going to be interested in you. I don’t think they’re going to let people be digitized without some kind of regulation involved.”

Since chemical fixation allows perfusate to remain in a liquid state, Jordan Sparks has suggested that molecular-scale nanotechnology may not actually be necessary for revival. He has written:

Stentrode is a currently available stent that gets implanted in a large blood vessel in the brain. It has electrodes on it, making it a brain-computer interface. Unlike its competitor, Neuralink, it does not damage neurons and it remains functional indefinitely instead of degrading over the course of a few months. It’s clear that this technology can be gradually improved. As we develop microrobotics, such implants could be designed to branch out into much smaller vessels. They could listen to the electrical activity of nearby neurons and also interact with them. This should result in decades of intensive development, where huge amounts of money would be poured into making gradual improvements because everyone would be using these implants. At some point, the resolution could approach that of individual neurons. It would also be obvious to everyone by then that an upload still has the same identity as the original brain.

Jordan imagines that eventually, people may choose to be digitized even if they are not near death.

The amount of available external computing power would be vastly greater than in the meat brain. And the speed would also be much higher. Remember that we only compute at about 10 bits per second and our memory retention is about 1 bit per second.

People would already be doing nearly all of their thinking on external hardware anyway. The early adopters would simply make the decision to remove the fairly useless legacy meat brains that were holding them back more than helping them. It would be a decision involving low risk with high reward.

I’m receptive to this kind of speculation, because it’s exactly the scenario that I described in the novel that I wrote 35 years ago. But I’m a bit more cautious now, having waited decades for truly transformative technology. In my experience, everything always takes longer than I expect.

In the interests of full disclosure, I have to mention that during my visit to Oregon in September, 2025 I signed the necessary documents, paid my $150, and am now a member of SBP. This is the first time I’ve had postmortem arrangements with any organization since I cancelled my Alcor membership in 2003.

With some embarrassment, I also have to mention one more little detail. This relates to Jordan’s announcement of his ambitions on CryoNet, 20 years ago, when one obnoxious individual used the word “clueless.”

That individual was me.

My apology is overdue because, obviously, I was very wrong. Jordan’s achievements in this field have been quite remarkable.

.png)