We conducted four experimental studies with a total of 4474 participants to investigate laypeople’s attitudes toward commodification. In Study 1, we examined whether participants would perceive specified transactions as more morally problematic when the good or service was exchanged for money rather than given for free. Study 2 explored whether participants’ evaluations of monetary transactions differed based on whether the transaction was described from the buyer’s or the seller’s perspective. In Study 3, we assessed whether unspecified transactions were viewed as more morally problematic if they involved money. Additionally, we investigated whether participants’ moral evaluations of an unspecified transaction would influence their views on a specified transaction. Finally, in Study 4, we investigated whether thinking first about the principled legitimacy of commodification alters participants’ subsequent moral evaluation of contested specified cases and vice versa.

The four studies were conducted online between July 2024 and February 2025. All participants were U.S. residents, and they were recruited from Prime Panels of Cloud Research, a platform for conducting online surveys (Litman et al., 2017). The surveys were programmed and administered with the help of the survey software Qualtrics. All studies were approved by the German Association for Experimental Economic Research (https://gfew.de/en). Furthermore, all studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. At the beginning of each study, written consent was obtained from all subjects, informing them that participation was voluntary and that they could quit the experiment at any time. All studies were pre-registered at AsPredicted.org, including sample size, data exclusion restriction, and planned data analysis.

Study 1: Testing for Anti-Commodification Attitudes in Specified Transactions

In our first study, we examined whether we could detect evidence of a negative attitude toward commodification in our participants. We tested this between and within subjects by confronting participants with uncommon specific transactions that either involved a transfer of money or not. The pre-registration of the study can be accessed via the following link: https://aspredicted.org/5n3w-q892.pdf.

Methods

745 participants took part in Study 1. They were randomly assigned to one of twelve treatments in a 2 (first transaction: sell vs. give) × 6 (context: kidney, queue, companion, dog, picture, piano) between-subjects design. After consenting to participate in our study, each participant read a vignette on two transaction partners who would, depending on the condition, either give and receive or sell and buy a certain good or service. For instance, in the kidney context, the vignette read as follows:

Peter has been on the waiting list for a kidney transplant for years. George is prepared to sell [give] Peter one of his kidneys. Peter gratefully accepts.

As can be seen, the two transactions differed only whether the word “give” or “sell” was plugged into the vignette. Table 1 shows all six contexts used in our study. After reading the vignette, the participants had to rate their agreement with three statements on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (fully disagree) to 6 (fully agree). These statements were the same in all contexts, except for the names of the respective transaction partners. In the kidney context, for instance, the statements were the following:

-

1. The interaction is morally problematic.

-

2. Peter acts morally problematic.

-

3. George acts morally problematic.

After the participants submitted their agreement with the three statements, they were led to another screen on which they were presented a second vignette describing another situation. The second vignette was always in the same context as their first vignette. That is, participants who read about a kidney transplant in the first vignette read about a kidney transplant in the second vignette as well; participants who read about a place in a queue in the first vignette read about a place in a queue in the second vignette as well; and so on. The only difference between the participant’s first and second vignette was the type of the transaction. Participants who had previously read the description of the sell case were now confronted with the give case, and vice versa. We made it clear to the participants that the second described situation differed from the first one in only one word and that this word was highlighted in the text (i.e., sell or give).

After having read the second vignette, participants were asked to rate their agreement with the same three statements shown above for the transaction described this time. For each of the three statements, we showed the participants their agreement to the same statement in the first vignette. Thus, we reminded the participants of their previous answer to make sure that they had not forgotten what they had stated in the previous vignette.

After the participants submitted their agreement with the three statements in the second vignette, a comprehension check question appeared on a separate screen. This question was about the content of the vignettes that they had read and gave participants a selection of four different answers of which only one was correct. Afterward, the participants answered a short post-experimental questionnaire to collect some demographic information.

Results

Of the 745 participants in Study 1, 710 answered the comprehension question about the content of the vignettes correctly. As pre-registered, the following data analysis is based only on the participants who passed the comprehension test. Of these 710 participants, 60% were female, 37% male, and 3% indicated another gender. The mean age of the study participants was 49 years.

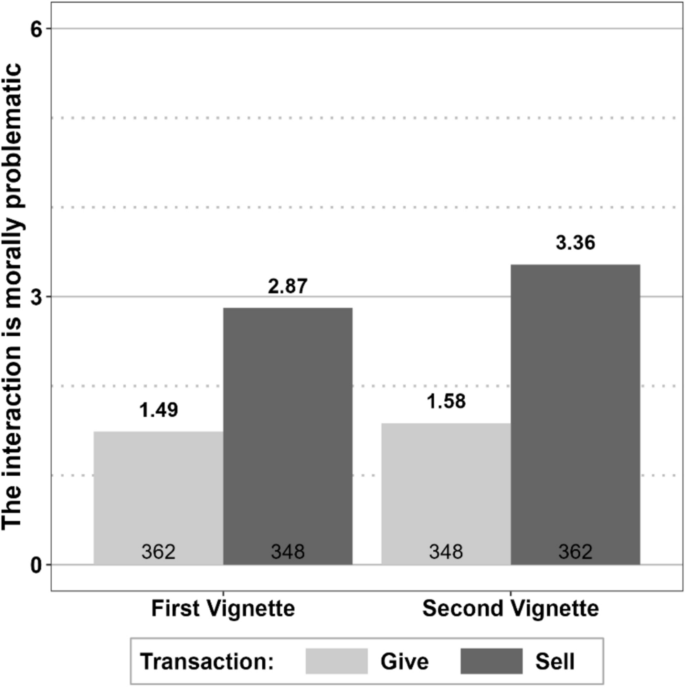

Figure 1 shows the average agreement of the participants with the statement of how morally problematic they find the respective interaction. Higher values indicate greater moral concerns. As can be seen in Fig. 1, moral concerns are greater when the same good or service is sold instead of given away. This is the case in the first vignette, as well as in the second vignette. Figure 9 in the appendix shows that these differences are consistently present in all six contexts.

The regression results in columns 2 and 3 of Table 2 show that the differences between the two transactions in the first vignette and in the second vignette are statistically significant. In the second vignette, the participants were described exactly the same interaction, with the only difference being that this time the good or service was given away if the participants had previously read the sell transaction, and that the good or service was sold if they had previously read the give transaction. As the regression results in columns 4 and 5 of Table 2 show, the participants adjusted their moral evaluation of the interaction in the second vignette to the respective transaction and deviated significantly from their first evaluation. Recall that we always reminded participants of their first rating. Forgetting their rating of the first interaction cannot have been the issue in our study.

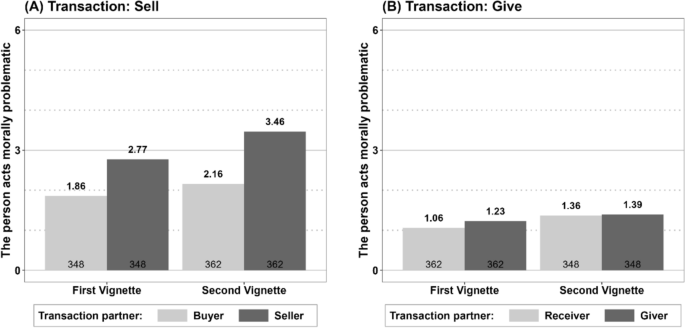

Figure 2 shows the average agreement of the participants with the statements of how morally problematic they find the act of the respective transaction partners. Again, higher values indicate greater moral concerns. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the transaction partners are perceived more morally problematic when the same good or service is sold instead of given away. This is the case in the first vignette, as well as in the second vignette. Moreover, when the good or service is transferred for money, the seller is perceived substantially more problematic than the buyer. Figure 10 in the appendix shows that all these observations are consistently present in all six contexts.

The regression results in columns 2 and 3 of Table 3 show that the ratings of the seller are significantly different from the ratings of the buyer in both vignettes. That is, the seller is always perceived to behave more problematic than the buyer in a monetary transaction. When the good or service is given away, the giver is perceived significantly more problematic than the receiver in the first vignette, but not the second. Moreover, the different ratings of both transaction partners in the first vignette are much less pronounced when the good or service is given away than when it is sold. We would like to note that the analysis of the transaction partners’ ratings was not pre-registered. However, the results show that the give-sell gap that we found in Study 1 may be due to the fact that we described the monetary transaction from the seller’s perspective. The seller is perceived much more problematic than the buyer and might thus dominate the perception of the transaction in general.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 indicate that our participants exhibit a pronounced anti-commodification attitude. This is evidenced by the systematically higher moral scruples regarding transactions involving monetary transfers compared to those that do not involve money. This effect is observed both between subjects and within subjects. The latter finding suggests that participants do not anchor their moral evaluations of the sell case to the give case and vice versa, thereby rejecting the ethical analogy between the two cases. The anti-commodification attitude remains robust regardless of the sequence in which participants address the two vignettes. Consistent with the overall moral evaluation of the transaction, the seller is viewed more negatively than the giver, and the buyer is viewed more negatively than the receiver. However, a direct comparison of the seller’s and the buyer’s moral evaluations reveals that the buyer is perceived in a less negative light than the seller. This finding supports previous evidence on the phenomenon of “intuitive mercantilism,” which suggests that people tend to believe that sellers benefit more from a transaction than buyers because they assign greater value to money than to goods (Johnson, 2018).

Study 2: Comparing the Seller’s with the Buyer’s Perspective

The more lenient evaluation of the buyer as opposed to the seller observed in Study 1 suggests that framing a transaction from the buyer’s perspective might erode the identified anti-commodification attitude. For this reason, we were interested in studying the effect that a reframing of the described situation by taking the buyer’s as opposed to the seller’s perspective would have on participants’ moral evaluations of the transaction. Study 2 was therefore conducted to test the robustness of the anti-commodification attitude in specific transactions established in Study 1. The pre-registration of the study can be accessed via the following link: https://aspredicted.org/yq7d-hfqm.pdf.

Methods

751 participants took part in Study 2. They were randomly assigned to one of twelve treatments in a 2 (transaction framing: selling vs. buying) × 6 (context: kidney, queue, companion, dog picture, piano) between-subjects design. After consenting to participate in our study, each participant now read a vignette on a transaction that would, depending on the condition, either be told from the seller’s perspective (sell condition) or from the buyer’s perspective (buy condition). For instance, in the kidney context, the vignettes in the sell and the buy condition read as follows:

Sell condition: Peter has been on the waiting list for a kidney transplant for years. George is prepared to sell Peter one of his kidneys. Peter gratefully accepts.

Buy condition: Peter has been on the waiting list for a kidney transplant for years. Peter is prepared to buy one of George’s kidneys. George gratefully accepts.

The vignettes therefore described the exact same transaction with the only difference that they were once told from the seller’s and in the other case from the buyer’s perspective. We used the same six contexts as in Study 1. In the sell condition, the vignettes were therefore identical to those shown in Table 1. Vignettes in the buy framing were adapted accordingly, as shown above. After reading the vignette, the participants had to rate their agreement with the three statements that we already used in Study 1.

After the participants submitted their agreement with the three statements, they were presented a second vignette. As in Study 1, the second vignette was always in the same context as the first vignette. The only difference was that the same transaction was now told from the perspective of the other transaction partner. This meant that participants who had previously read the situation of a transaction told from the seller’s perspective were now confronted with the buyer’s perspective, and vice versa. After having read the second vignette, participants were again asked to rate their agreement with the three statements, this time with respect to the reframed situation. For each of the three statements, we showed the participants their agreement to the same statement in the first vignette. Thus, we again reminded the participants of their previous answer to make sure that they had not forgotten what they had stated in the previous vignette.

As in Study 1, participants also had to answer a comprehension check question on a separate screen. Afterward, the participants answered a short post-experimental questionnaire to collect some demographic information.

Results

Of the 751 participants in Study 2, 702 answered the comprehension question about the content of the vignettes correctly. As pre-registered, the following data analysis is based only on the participants who passed the comprehension test. Of these 702 participants, 61% were female, 37% male, and 2% indicated another gender. The mean age of the study participants was 48 years.

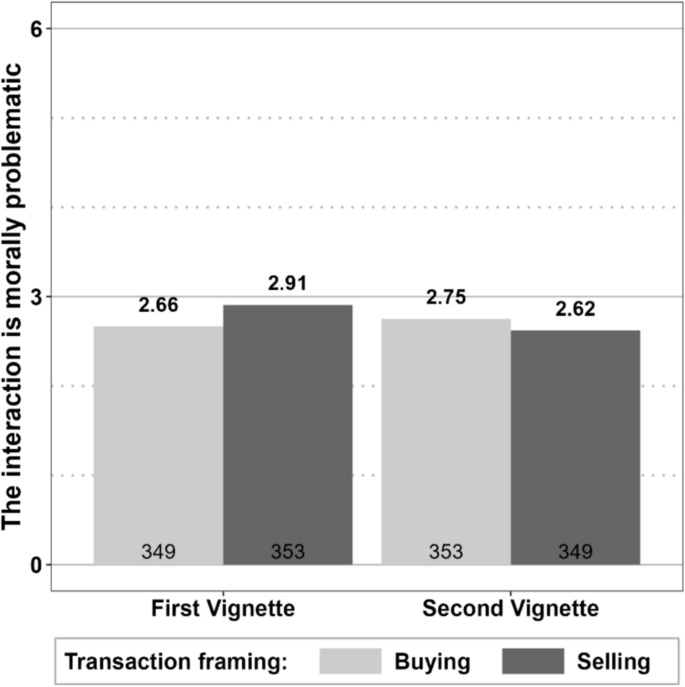

Figure 3 shows the average agreement of the participants with the statement of how morally problematic they find the respective interaction. Again, higher values indicate greater moral concerns. As can be seen in Fig. 3, moral concerns were similar, no matter whether the transaction was told from the buyer’s or the seller’s perspective. This is the case in the first vignette, as well as in the second vignette. Figure 11 in the appendix shows that this pattern is consistent in all six contexts.

The regression results in columns 2 and 3 of Table 4 show that the moral concerns between the two transaction framings in the first vignette as well as in the second vignette do not differ significantly. Likewise, the regression results in columns 4 and 5 of Table 4 show that the participants did not significantly adjust their moral evaluation of the interaction in the second vignette to the respective transaction framing. Apparently, from a moral perspective, the participants perceived the transactions to be similar, independent of their specific framing.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 show that our participants did not regard a contested monetary transaction in a more positive light if it was told from the buyer’s as opposed to the seller’s perspective. This was true in a between-subjects as well as in a within-subjects comparison. This finding suggests that the anti-commodification attitude identified in Study 1 is robust to alternative framings of the situation. In particular, the phenomenon of intuitive mercantilism, which describes people’s intuitive denial of the mutual improvement underlying voluntary transactions and expresses the idea that the seller benefits at the buyer’s expense, is not reflected in this result.

Study 3: Testing for General Anti-Commodification Attitudes and Deductive Moral Judgments

Given the robustness of the anti-commodification attitude demonstrated in Studies 1 and 2, we are now interested in exploring whether this attitude exists more generally, beyond specified transactions. To this end, we aim to establish the phenomenon observed in the previous studies for unspecified transactions. Additionally, we seek to determine whether there is evidence of moral spillovers from unspecified to specified transactions. In other words, we are curious whether a less pronounced anti-commodification attitude in an unspecified transaction leads to weaker moral concerns in a specific context. The pre-registration of the study can be accessed via the following link: https://aspredicted.org/j8x6-yw7z.pdf.

Methods

1479 participants took part in Study 3. They were randomly assigned to one of 24 treatments in a 2 (number of vignettes: two vs. one) × 2 (transaction: sell vs. give) × 6 (context: kidney, queue, companion, dog, picture, piano) between-subjects design. After consenting to participate in our study, each participant read a vignette on two transaction partners who would, depending on the condition, either give and receive or sell and buy a good or service. If the participants of Study 3 saw only one vignette in total (treatment Baseline in the following), we basically repeated the conditions of the first vignette in Study 1. That is, the participants in treatment Baseline read either the sell case or the give case of one of the six contexts shown in Table 1. If the participants of Study 3 read two vignettes in total (treatment Unspecific in the following), the first vignette described an interaction of two transaction partners who would engage in an unspecified transaction. For instance, in the case where George and Peter are the two transaction partners, the unspecified transaction in the sell [give] case simply read:

George is prepared to sell [give] something that he owns to Peter. Peter gratefully accepts.

We used six different versions of the unspecified transaction which differed only with respect to the names of the two transaction partners. We made sure to match the names of the transaction partners in the specific contexts shown in Table 1. After reading the first vignette, all participants had to rate their agreement with the three statements that we already used in Studies 1 and 2. Participants in treatment Baseline rated the statements with respect to the corresponding specified transaction. Participants in treatment Unspecific rated the statements with respect to the corresponding unspecified transaction.

After the participants in treatment Unspecific submitted their agreement with the three statements, they were presented a second vignette. For all participants, the second vignette described an interaction of the same type of transaction. That is, participants whose first vignette was about selling a good or service, received a second vignette about selling a good or service again; participants whose first vignette was about giving away a good or service, received a second vignette about giving away a good or service again. In contrast to an unspecified transaction in the first vignette, the second vignette now contained a specified transaction. The specified transaction contained one of the six contexts shown in Table 1. We made sure that the names of the transaction partners remained the same for each participant from the first to the second vignette. Thus, participants who read an unspecified transaction with George and Peter in the first vignette read in the second vignette about a specified transaction in the kidney context where, again, George and Peter were the two transaction partners. After having read the second vignette, participants in treatment Unspecific were asked to rate their agreement with the three normative statements, this time with respect to the specified transaction. For each of the three statements, we showed the participants their agreement to the same statement in the unspecified transaction. Thus, we again reminded the participants of their previous answer to make sure that they had not forgotten what they had stated in the previous vignette.

As in Studies 1 and 2, all participants had to answer a comprehension check question on a separate screen. Finally, the participants answered a short post-experimental questionnaire to collect some demographic information.

Results

Of the 1479 participants in Study 3, 1402 answered the comprehension question about the content of the vignettes correctly. As pre-registered, the following data analysis is based only on the participants who passed the comprehension test. Of these 1402 participants, 61% were female, 38% male, and 1% indicated another gender. The mean age of the study participants was 50 years.

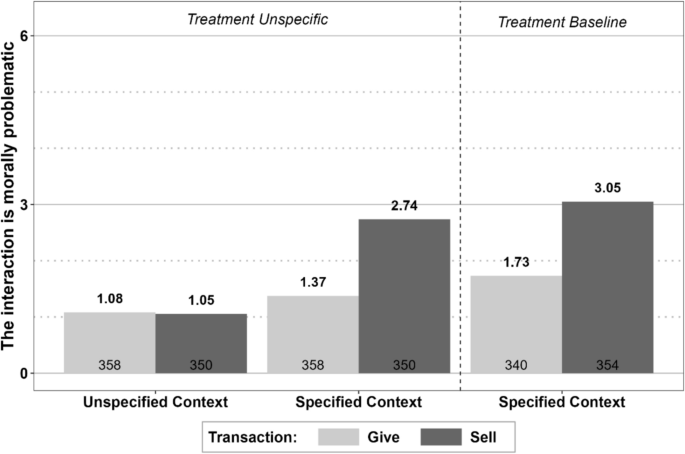

Figure 4 shows the average agreement of the participants with the statement of how morally problematic they find the respective interaction. As before, higher values indicate greater moral concerns. As can be seen in Fig. 4, participants’ moral concerns in the case of an unspecified transaction are on a low level overall and virtually identical in the give and the sell case. In the specified transaction, moral concerns are again greater when the same good or service is sold instead of given away. This is the case when the specified transaction appeared in the second vignette of treatment Unspecific and in the first vignette of treatment Baseline. Figure 12 in the appendix shows that the latter pattern is again consistently present in all six contexts.

The regression results in columns 2 to 4 of Table 5 show that the moral concerns between the two types of transactions in the unspecified case do not differ significantly (see column 2), whereas they do differ significantly in the specified cases (see columns 3 and 4). In specified cases, transactions are again perceived to be more morally problematic when they involve monetary transfers. The regression results in column 5 of Table 5 suggest that the moral concerns in the specified transactions are slightly higher overall in treatment Baseline than in treatment Unspecific. Thus, reading the unspecified transaction first reduced participants moral concerns in the specified transaction slightly in both the give and sell case. However, the give-sell gap (i.e., the anti-commodification attitude) in the specified transactions did not differ significantly between treatment Baseline and treatment Unspecific (see column 5 in Table 5). Participants in treatment Unspecific significantly adjusted their moral evaluation of the specified transaction in the second vignette in the give and sell case (see columns 2 and 3 of Table 6), but substantially and significantly more in the sell than the give case (see column 4 of Table 6). Apparently, there were no significant spillovers toward commodification attitudes from unspecified to specified transactions.

Discussion

The findings of Study 3 imply that an anti-commodification attitude regarding transactions phrased in general terms did not exist. It was only in specified situations that the effect could be found. That participants tend to deem the selling and buying of an unspecified good or service in general as morally unproblematic, however, does not spill over to the evaluation of a voluntary transaction of a specific good or service. This means that participants do not necessarily deduce their moral judgment of a specific case of commodification from their judgment of a more general case. In fact, it turns out that the anti-commodification attitude is not even mitigated by having participants first reflect on their attitude that voluntary commercial exchanges of unspecified goods or services are generally morally unproblematic.

Study 4: Reflective Equilibrium between Case and Principle

In a final step, we are now interested in whether the participants’ attitudes toward commodification can be brought into a reflective equilibrium (Rawls, 1999). To this end, we pursue two interventions in the participants’ deliberation process. First, we ask about the simultaneous evaluation of the sell and give cases in a specified context. The participants should thus be made aware of the analogy between the two types of transaction in a specific case by means of direct comparison. Second, we confront the participants with the general principle proposed by Brennan and Jaworski (2015a) that it must be morally permissible to do something for money if it is permissible to do it for free. We then examine the extent to which this general principle affects the evaluation of the specific case and vice versa. The pre-registration of the study can be accessed via the following link: https://aspredicted.org/tscg-4x67.pdf.

Methods

1499 participants took part in Study 4. They were randomly assigned to one of 12 treatments in a 2 (sequence of events: case-principle-case vs. principle-case-principle) × 6 (context: kidney, queue, companion, dog, picture, piano) between-subjects design. After consenting to participate in our study, each participant encountered various tasks in a three-stage process. The tasks involved either evaluating a specific case or assessing a general principle. The specific case consisted of a description of a transaction between two people in one of the six contexts shown in Table 1. This time, however, both types of transactions (i.e., give and sell) were presented to the participants at the same time. That is, at this stage, the participants faced two situations in the same context, which only differed in whether the good or service was given away or sold. The order of appearance of the two situations on the participants’ screens was randomized. The participants’ task was to rate their agreement with the three aforementioned normative statements for each of the two situations. Agreement with the statements was queried in matrix form. This meant that the participants first evaluated the general interaction for both situations and then the individual transaction partners for each of the two cases.

When the participants were asked to assess a general principle, we presented them the following statement based on Brennan and Jaworski (2015a):

If it is morally okay to do something for free, it is also morally okay to do it for money.

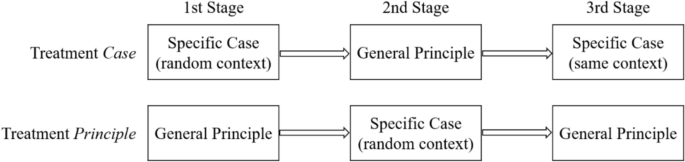

Participants then had to give a binary answer of whether they agreed or disagreed with this statement. The sequence of tasks differed between the experimental conditions (see Fig. 5). In one condition (treatment Case in the following), participants first evaluated a specific case, then the general principle and then again, the same specific case as in the first stage. In another condition (treatment Principle in the following), the participants first evaluated the general principle, then a specific case and then the general principle again. In the third stage, the participants were thus confronted with the same task as in their first stage. To ensure that the participants had not forgotten what they had stated in the first stage, we reminded them of their previous answer(s).

As in Studies 1 to 3, all participants had to answer a comprehension check question on a separate screen. Finally, the participants answered a short post-experimental questionnaire to collect some demographic information.

Results

Of the 1499 participants in Study 4, 1405 answered the comprehension question about the content of the vignettes correctly. As pre-registered, the following data analysis is based only on the participants who passed the comprehension test. Of these 1405 participants, 60% were female, 39% male, and 1% indicated another gender. The mean age of the study participants was 49 years.

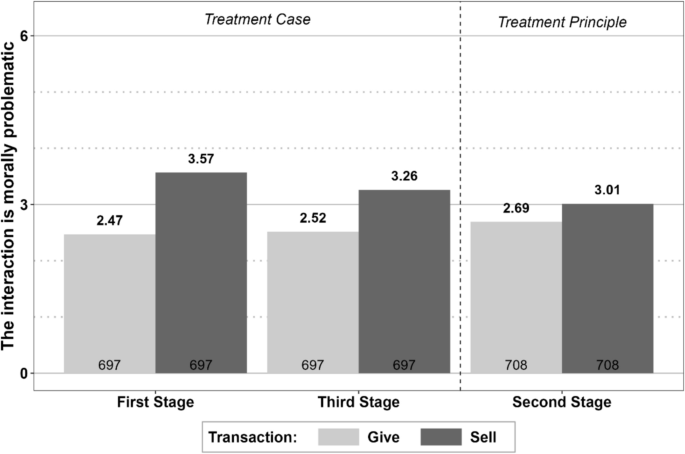

Figure 6 shows the average agreement of the participants with the statement of how morally problematic they find the respective interaction. Again, higher values indicate greater moral concerns. In treatment Case, participants’ moral concerns are greater when the same good or service is sold instead of given away. This is the case in the first stage (i.e., before assessing the general principle) and in the third stage (i.e., after assessing the general principle). The differences in moral evaluations, however, appear to be slightly less pronounced after the participants have assessed the general principle in treatment Case. In treatment Principle, the differences in moral concerns when the same good or service is sold instead of given away seem negligible. Figure 13 in the appendix shows that the pattern of greater moral concerns about monetary as opposed to free transactions in treatment Case is consistently present in all six contexts in both stages, while this is no longer true for treatment Principle.

The regression results in Table 7 show that the give-sell gap is significantly present in both stages of treatment Case (see columns 2 and 3). Participants’ moral concerns in this treatment are significantly higher when a good or service is sold than when it is given away, even though both transactions were shown simultaneously. Thus, participants purposefully differentiated between the two types of transactions in their moral assessment when the sequence of tasks started with the specific case. In contrast, in treatment Principle, the give-sell gap is not significantly present (see column 4). Consequently, the give-sell gap in this treatment is significantly smaller than in both stages of treatment Case (see columns 5 and 6). When the sequence of tasks started with the general principle, this apparently led to an alignment of the moral assessment of both transaction types. But also in treatment Case, the examination of the general principle led to a significant reduction of the give-sell gap in the third stage (see column 7). Participants reconsidered their initial assessment of the two types of transactions and reduced some of their previous moral aversion.

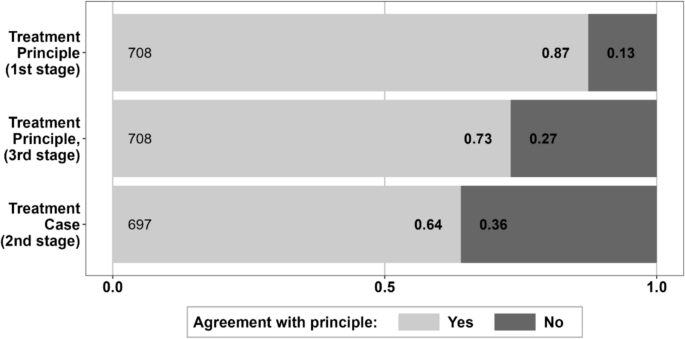

Figure 7 shows the participants’ agreement with the general principle. First of all, it can be seen that the majority of participants in both treatments and in all stages agree with the principle. When the sequence of tasks starts with the assessment of the general principle, 87% of the participants agree with it. This is a significantly higher rate of agreement than the 64% in treatment Case, in which the participants first consider the specific case before being confronted with the general principle (χ2 = 103.9, p < 0.001). When the participants in treatment Principle reconsider their agreement after they have evaluated the specific case, the rate of agreement drops significantly to 73% (McNemar’s χ2 = 65.4, p < 0.001). Nevertheless, the rate of agreement here is still higher than in treatment Case (χ2 = 13.3, p < 0.001).

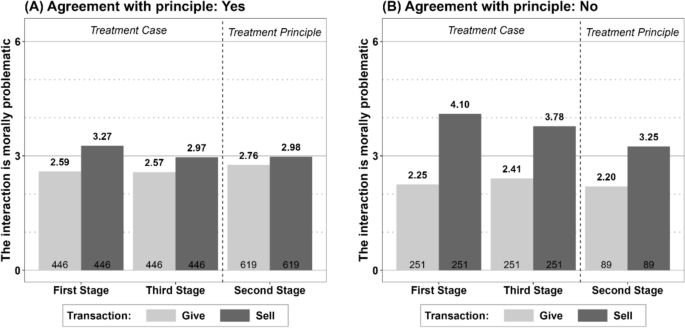

Figure 8 differentiates the average agreement with the statement of how morally problematic the specific interaction is according to the participants’ agreement with the general principle. In treatment Principle, the agreement refers to the participants’ answer in the first stage. As can be seen in the figure, the give-sell gap is larger in both treatments for participants who rejected the general principle. Furthermore, the give-sell gap is larger when participants first evaluated a specific case, regardless of whether they later agreed (see also column 2 in Table 8) or disagreed (see also column 5 in Table 8) with the general principle. Finally, the give-sell gap in treatment Case decreases after evaluating the general principle. This applies to participants who agreed (see also column 4 in Table 8) and disagreed (see also column 7 in Table 8) with the general principle in the second stage.

Discussion

The anti-commodification attitude observed in our previous three studies persists even if participants were tasked to evaluate the sell and give cases in a specified context simultaneously. Making them aware of the analogy between the two cases by means of direct comparison did thus not erode anti-commodification attitudes. However, confronting participants with a general principle on the legitimacy of commodification weakened their anti-commodification attitudes in specified contexts. But the starting point mattered. If participants were exposed to the general principle first, their anti-commodification attitude disappeared in subsequent specific transactions. If participants started with assessing specific transactions first, the general principle helped to reduce anti-commodification attitudes, but they did not vanish completely. Interestingly, anti-commodification attitudes were reduced for those participants who agreed as well as those who disagreed with the general principle. Agreement with the principle on the legitimacy of commodification was generally high. Examining an uncommon specific transaction reduced agreement with the principle. Agreement was lowest when participants started their thought process by examining an uncommon specific transaction.

.png)