Please check out this lovely review of my first published novel, The Mind Reels, which is available for purchase now at all manner of online retailers and (likely) at your local bookstore. You can also purchase audiobook or ebook versions. The book was a labor of love about an issue of great personal investment and knowledge on my part, representing a point of view that is almost entirely unseen in our cultural media. Please consider picking up a copy and spread the word.

I write the words and, I hope, people will read them.

My own experience tells me in the strongest possible terms that every piece of writing that’s worth anything has to begin as something the writer would want to read themselves, that you satisfy your own curiosities and sensibilities before you start worrying about what anyone else might think. I wrote my first book because, in the heart of my grad school era disillusionment with our education system, I went looking for a book just like that and couldn’t find one; I wrote my recent novel because I was all too aware that no one else would. I am sure that this is the only way to do it. There’s a basic dishonesty in trying to reverse-engineer an audience’s taste, after all. You end up with work that’s pandering, shallow, and self-conscious, the artistic equivalent of laughing at a joke you don’t find funny because you think you’re supposed to. But even beyond dishonesty, I just don’t think it works, or at least it would never work for me. You can’t predict the market or preemptively tailor yourself to what will “resonate,” because what resonates is authentic - someone clearly thinking, feeling, and shaping ideas according to their own compass, which is to say, in defiance and ignorance of that which their audience wants from them. And frankly I think part of the reason that many people are quietly but deeply dissatisfied with the pop culture available to them, in any genre or medium, is because in a digital world artists and creators are too aware of the desires of their fans.

The paradox of art meant to be shared is that the only way to make something that connects is to make something that doesn’t try to connect, not directly; it just is what it is, if you’ll forgive that empty cliche, an honest manifestation of the person who made it, something out of their control. You have to begin from what you value, what you find beautiful or true or absurd or terrifying, because otherwise you’re just borrowing someone else’s sense of those things. Even if you’re wrong, even if (especially if) your instincts are idiosyncratic or unpopular, at least you’ve made something real. You can’t outsmart the audience, but you can be sincere enough that they recognize themselves in your sincerity. That’s the only real transaction available in art or craft: you go first, you show yourself, and maybe someone else sees it and thinks, “yes, that’s how it feels.” Whether my work is worthy of this kind of high-falutin talk is not for me to decide.

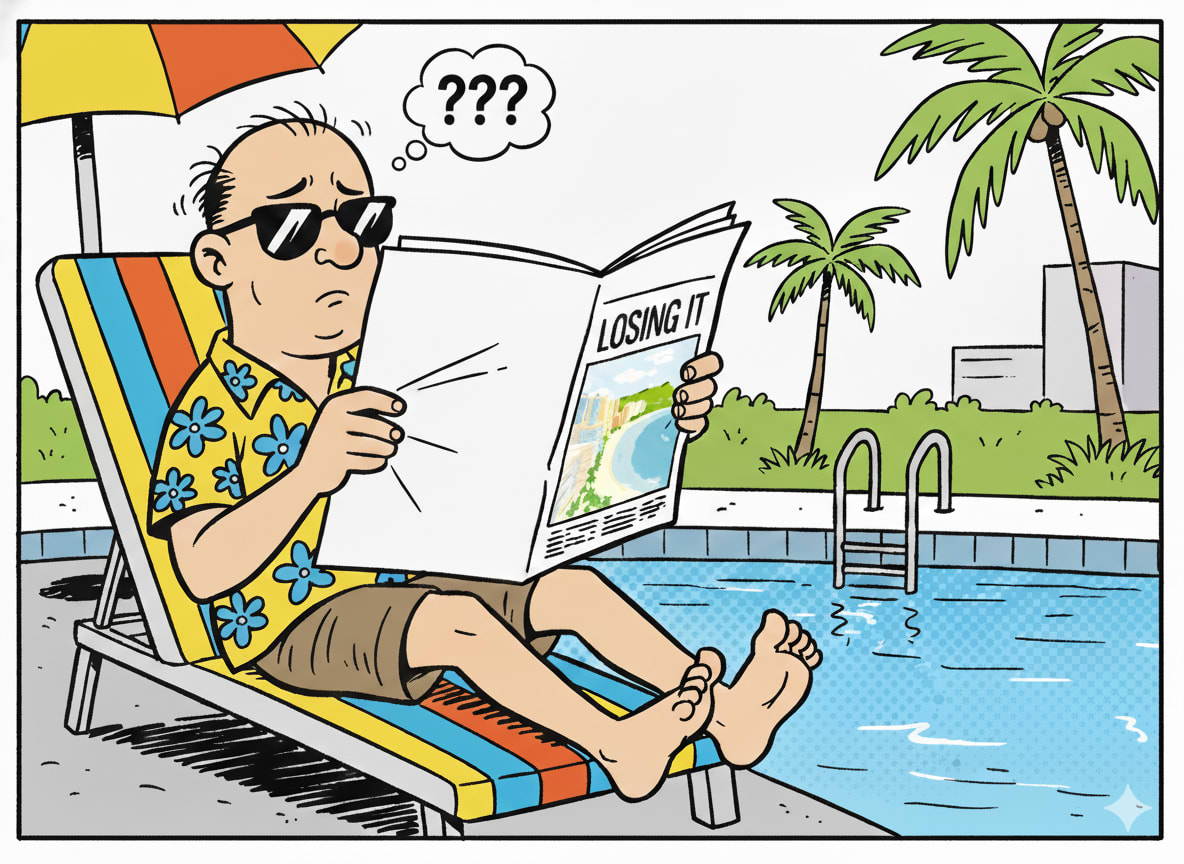

All of that is a somewhat-pretentious throat-clearing to get to the point of today’s post: to wonder why people react to the things I write the way they do. In order to work through these ideas, I’m picking a particular piece of mine and discussing its reception - its non-quantitative reception, mostly. I’ve said many many times that the misery of doing the kind of writing I do (generally and crudely, short-form argumentative nonfiction) is that the stuff you really care about and labor over immediately dies on the vine while a dashed-off blog post that you didn’t think twice about goes mega-viral. Here though I’m much less interested in the numbers (which were above average in terms of views and likes) than in audience reaction - what people have said about a particular piece, who liked it, who didn’t, and why each side felt the way they did. You see, the paradox is that I believe all of the things I said at the top, very passionately, and genuinely do always write with the intent of pleasing myself first… but I also am deeply alive to the reception of my work among the audience, and frankly find the performative disaffection a lot of other writers engage in about audience reception to be annoying and fake. I don’t know. I contain multitudes.

For this exercise, I’ve picked this essay of mine from June 2nd, 2022. It was published a little more than a year into the life of this newsletter and written on the occasion of my 41st birthday. It’s the true story of how I lost my virginity. And I’m going to explain it to you as part of my effort to understand the response to it. Many readers passionately loved this essay, a few passionately hated it, and there were some who thought that this is not the sort of work I should publish at all. To make sense of the difference, I’m going to do what any writer hates to do, which is to explain his writing. When he was asked what his poems meant, Robert Frost would always say “What do you want me to do, say it back in worse English?” I’m no Robert Frost, and I don’t write poetry, but I too hate to go through the laborious process of saying “This is what I meant by X,” when conveying X without directly saying it is kind of the whole game. But I can be convinced to do so in the name of marketing, and I will do it here, for all of you, so that we might better understand each other. I hope that some of you find this a worthwhile exercise. First things first: read that essay!

OK, so - what was I trying to do? There’s a few things.

In the simplest sense, this was my attempt to publish a memoir-style piece about a deeply personal and physically awkward experience which led to some personal and emotional maturation that were achieved only through a little heartache. On the most basic level, I had this experience of being brought into a new phase of adulthood by a woman I found very mysterious - in exactly the way romantic young men always find women mysterious, which as I will explain later can hide a little darkness - and it’s one of the few experiences of my life that I find worth telling in simply narrative terms. (My experience learning about 9/11 is also a good story, as is my story of getting trapped between the seats at a movie theater with NBA star Ray Allen.) I just find this narrative kind of poignant, and I thought it might be worth telling. I also think there’s a lot of concern about young men, out there, and how they develop and in particular how their attitudes towards women are developed, and I thought this might be a useful volley in that effort. Another way to put this is to say that I was trying to use a story about a very young man to understand how a middle-aged one came to be.

If you’d like a bit of meta sprinkled on this, it’s certainly the case that I was thinking of the personal essay and its conventions when I was composing this piece. The term “personal essay,” as I’ve written before, is a loaded one in the world of professional media, and an intensely gendered one. I wanted to write this story in part because if I was a woman and had published an identical story, albeit with the gender roles reversed, no one would have batted an eye - and as I’ll talk about when I reflect on the reception of the piece, a few people did bat an eye.

Another big thing I was trying to do is something I’m always pawing at: to embed criticism in sympathy in a way that complicates simplistic approval or criticism. A big part of the point of this essay is that I was enraptured by the young woman who I first had sex with, was perhaps treated a little roughly by her, but also treated her poorly in my young romanticism and inability to comprehend of her as her own person. This is, if anything, the most relentless message of the piece: that my desire for her, and my unchosen but still foolish falling in love with her, were ultimately shrouded in a kind of self-centered way of thinking about women that I suspect is very common among young men, particularly among a certain set of young romantics who find love a uniquely uncrackable puzzle. The whole terrifying engine of youthful desire, for a particular kind of sad-sack male like I was, is rooted in an almost perfect solipsism; that I think this is forgivable (indeed, that I was asking for forgiveness) is pretty much directly stated in the piece. The essay is first and foremost a confession of that profound self-absorption. It’s the painful memory of a young man who was so caught up in the fact of his own loneliness that he couldn’t recognize the basic humanity, let alone the agency, of the woman standing right there. I thought that this, of all elements in the essay, would have been plain, the self-critical and embarrassed but human element. But again we’ll talk about it in a bit.

And that brings us to the most straightforwardly idea-bearing aspect of this story, which lies in my discovering my own capacity to be attractive. If there’s a point to the story beyond the experience of my first time having sex itself, of simply sharing this intense and intimate and awkward and fundamentally illogical aspect of being human, it’s that: the unexpected, unearned moment when someone signaled that I was, against all the evidence of my high school report cards and my self-hatred, desirable. It wasn’t just a physical thing, to have sex, obviously, it was a psychological shock, one driven by the sudden, life-altering understanding that I might sometimes be desired. Again, this kind of revelation is common in essays written by women but still strangely kind of taboo in those written by men. It was a big deal, for me - to be seen, truly seen, not as a pathetic loser but as a potential lover, and by a woman who I took to be straightforwardly desirable herself, detonated every carefully constructed narrative I had about myself. It was like the moment in the novel where the protagonist’s core self-understanding is suddenly invalidated by some mysterious outside force. I think that’s worth writing about: the sudden, partly invigorating, partly humiliating discovery that you were wrong about yourself, and that your pain was, in part, a self-inflicted myth you had spent years constructing.

I really do, for the record, believe that this is a big part of the puzzle of heterosexual attraction that “incels” fail to understand: women can sense the disbelief these men feel at the idea that they might be desired, and it makes them undesirable. I don’t mean this in a “fake it til you make it” way, and this isn’t yet another endorsement of BEING CONFIDENT, the false god of male sexual attraction. Instead, it’s a simple observation that men who know that they might be desired by women act differently than men who don’t yet believe that, and women can pick up on this in a way that’s very salient for who is attracted to whom. I think a lot of men dramatically underestimate the importance of ease when it comes to getting laid; because it doesn’t happen to them very often, they approach moments where it seems like they might have an opening with sweaty palms and a hitch in their throat and anxiety in their soul, and women pick up on it and say “Oh dear, this is a very big deal to this gentleman, there’s a lot of pressure, ABORT.” I think that happens all the time - a dude makes it plain to a woman he’s chatting up that the opportunity seems like a very big deal and he’s all anxious about it, and the possibility of a simple fun encounter dissolves, and she’s not into it anymore. This is crucially different from the commandment to be confident, which often contributes to exactly the wrong behaviors: men try to project confidence, which is an affectation, and women can feel the affect, and it is the opposite of the ease that I’m identifying as core to casual desire.

I truly think that a lot of men would be much better served in the “sexual marketplace” if they could fully understand that their pent-up longing and anxiety make sex feel like a big nervy deal, and that most people reflexively avoid big nervy deals. Instead, the ideal approach should broadcast to your prospective sexual partner “Hey, I’m attracted to you, and it’d be cool if you’re attracted to me, but I’ve been here before and if you aren’t, it’s not going to ruin my week, because this is all laid back and no biggie and maybe something fun can happen.” Of course, embodying this is easier said than done, which is part of what I was trying to say in this piece: I couldn’t feel that way until a woman who was unapologetic about her desire and fully confident in herself demonstrated to me that I was a being that could be worthy of feminine desire, and to be honest I didn’t fully get a handle on all of that until my 30s, really, which was when sex truly ceased to be a site of anxiety and instead a source of fun, and I fully grokked that understanding my own desirability wasn’t a matter of delusion or arrogance but just a healthy, comfortable reality. Obviously, none of this changes the fact that attraction is primal, based largely on physical features and other things the individual can’t fully control, and not fair. It’s not like every guy can suddenly feel this way and get laid. But as I’ve written before, a ton of ordinary guys don’t get laid because they can’t believe that they’re worthy of receiving women’s attraction. I firmly, firmly believe that.

This all brings me to a set of problems that I’ve never been able to solved and that I’m not sure can be solved in an essay format. I’ll start by way of analogy: there is no cool way to say that I am a large man in writing. None. I’ve been trying to crack that particular nut for a long time. The main reason for this is distressingly psychologically obvious: for years and years, when I’ve met people who only know me for my written work, I’ve been told “You’re bigger than I thought you’d be!” If I were 6’6 and 300 pounds instead of 6’2 and 235ish pounds, this would probably be more understandable. But I’m just kind-of-big, rather than really big - my old beloved dog Miles was always right on the weight border between being a big medium dog and a small big dog, and I am right there with him. I’m big but not, like, “wow that’s a big guy” big, just a big guy, if you follow me. And so I’ve always asked “Do I write like a small guy?” in a joking way, and too often they’ll say “Well yeah, sort of!” This is inscrutable and abstract and meaningless and yet it bothers me more than it should. More importantly, there are basic intelligibility consequences to this stuff; because I’ve never been afraid to write autobiographically, I sometimes need to convey certain physical and social realities of my life, particularly given that a large man with a psychotic disorder is something different from a small woman with a psychotic disorder. But there’s just no way to report this information gracefully; it’s too central to questions of male value and masculine ideals to not seem pregnant with… stuff.

Well, if you think finding a way to talk about being a larger-than-average fellow is awkward, try expressing the reality that in adulthood you became a man of ordinary sexual success! What haunts this essay is that I stopped being that awkward skinny kid who couldn’t comprehend that he could be desirable, right - I did, in fact, go on to be a reasonably successful man-who-has-sex-with-women, and this experience was core to finding myself, again because it was transformative to be confronted with the simple reality that there were desirable women who desired me. But there is simply no way to convey that basic fact, that I have not in fact been entirely unsuccessful when it comes to picking up women, in the written form without sounding like a complete jackass. We are, as a species, incredibly sensitive to the perception that a man is being sexually braggadocios; that I was not in fact bragging about unusual success as a ladies man but simply stating my ordinary level of healthy promiscuity never really made any difference. I simply have never found any way to say, gracefully and with appropriate self-deprecation, that there have in fact been women who have found me not entirely loathsome and who have made the informed and adult decision to bring me into their beds. Even though, as hard as it may be to believe - well, there have been those who have.

So let’s talk reactions. First, I must give special attention to one particular woman who wrote me an angry email (and then another and then another) because I had pointed out that the woman I lost my virginity to had “very nice tits.” She found this unconscionably sexist and crude. Well, maybe I didn’t pull this moment off - that’s always a possibility - but for the record, a) I did try to make it clear that this was a somewhat-embarrassed aside, b) she did have very nice tits, and c) these details simply are a core element of being a late adolescent boy who is falling in love with someone who has made it clear he should do anything but. And I also think this is another gendered reaction; the “A Guy I Fucked Had a Magic Dick, and It Ruined My Life” is a very time-tested commonplace in the women’s personal essay category. And that’s not a bad thing, given that these elements of our sexual lives are real and important. So I’m sorry, lady, but I wrote it because I thought the detail mattered, and if you’re too delicate for it, read something else.

And then there was the small but persistent number of people who hated the essay, definitely smaller than the number of people who loved it, anyway. Recently I shared the essay on Substack Notes for no particular reason, and I was told by a reader that he loved it but his girlfriend hated it. It’s not the case that this essay was generally liked by men and hated by women - in fact the people who have written to me to express the deepest praise have been women - but it is the case that the criticism of this essay has taken on a (for lack of a better term) feminist bent. They complain that the story does, well, pretty much what I explicitly wanted it to do: to showcase the perspective of a young man who was generally well-meaning and truly infatuated with a young woman but who was incapable of seeing her as fully human. Again, that was more or less the point of the whole thing! And yet I have heard from many readers who felt that the piece didn’t do enough to center the agency or interiority of the woman involved. That the piece labored hard to acknowledge this failing has never satisfied them. I tried to make it clear that my infatuation was, in a certain sense, self-obsessed and erasing of her individuality, and I continue to think that there is an undeniable amount of sad, aged self-criticism in the piece. One thing I have learned, though, these past twenty years, is that there are many readers who simply cannot hear anything you don’t say in the most ponderous and explicit terms possible. That doing so would kill all the art in the thing doesn’t matter to them.

For the record: I couldn’t possibly write that woman’s interiority for her, and not just because I haven’t seen her in a quarter-century and can’t remember her face. I can only write my own interiority. That is both the promise and the limitation of memoir. But I also accept that telling a story about someone else inevitably exerts pressure on them, though I would be absolutely shocked if she ever saw the essay and frankly also shocked if she recognized herself in it. I mean this, I guess, symbolically and spiritually as well as literally. To the extent that she remains a cipher in my telling, I acknowledge that is my failure and not merely a feature of genre. It just also happens to be kind of the point of my essay. My defense is not denial but an acknowledgement: I was, and am, shaped by my particular solipsism. If the essay leaves the woman too thin, it’s a fair criticism, and also an illustration of precisely the default error of young men I wanted to portray. The very fact that readers called that out shows the piece was, in one sense, working; people recognized the pattern and didn’t shrug it off.

I don’t know if it makes sense on the most basic literal level to say that you have sympathy or empathy for yourself, but, well I did and do, and maybe that is what the essay’s critics are reacting to. Certainly there is an understanding of that young man’s unique pain and loneliness, an orphan thousands of miles away from everyone he has ever known, incapable of loving himself and desperate to be loved by others. I guess some of the essay’s critics would much prefer that I see nothing worth forgiving in my younger self. But it turns out that I do, and I think that if we are ever to evolve beyond the particularly male way of seeing women as minor parts in the drama of their desire, we need to cultivate that sympathy even if we’re not sure the objects of it deserve it. Perhaps that is another feature of this essay: the understanding that sympathy is sometimes not deserved by still demanded, that sometimes we need to feel for those who did not understand.

The gendered double standard about vulnerability and desire is, perhaps, a larger cultural axis here that’s worth naming, because it’s where a lot of the heat in the responses comes from. Confessions of shame and desire from women, particularly young women writing about early sexual encounters, tend to be read through frameworks of power, exploitation, and systemic constraint; they are allowed, with reason, to be complicated. Male confessions, by contrast, are often treated by the public as either unambiguous misbehavior to be punished or as self-pity to be dismissed. The response to my piece tracked those fault lines: some readers heard a redeeming arc, some saw a play for solicited (and thus illegitimate) absolution, and some correctly heard an insufficient accounting from a flawed and limited man talking about his more flawed and more limited adolescent self. All of those reactions are legitimate readings, and I suppose that the variance says more about the listeners than the narrator, more about the readers than the writer. The job of the writer is not to control the listener’s economy of value but to be clear enough about intent and consequence that disagreement can be substantive rather than merely performative. For some, that intent was not clear.

Well, I can simultaneously acknowledge that the error was mine and also that I would not do it differently; for me, there does in fact have to be some level of art to it, and writing “it was wrong of me to erase that woman’s individuality in the heat of my adolescent passions” would kill the art. I’m sorry. I have to serve myself first. That’s the writer speaking, or perhaps it’s the man in me. I tried my best to make my self-criticism plain. If it’s not sufficiently present for my critics, they are entitled to their feelings. And the many people who saw something rare and delicate and vulnerable and true in my piece are entitled to their feelings too.

If the piece did anything useful, it might be this: it made visible a particular mechanism of harm that’s embarrassingly ordinary, the way romanticized loneliness can blind a young man to another person’s subjectivity. That blindness is not an exotic pathology; it’s a socialized habit. Spotting it in oneself is the first, necessary step to unlearning it. That’s not a theatrical absolution, or so I hope, but rather the beginning of responsibility. You don’t get to insist “I was young” as a full defense, but you do get to use your memory as evidence for change. That’s the awkward transaction that I hope my essay would seduce the reader into taking part in: I wanted show you how I was wrong, to force you to test the sincerity of that showing, and if the test passed we might move, perhaps haltingly, toward something less self-centered, but also more sympathetic. That was all my gamble, and I’d like to think that I won.

If I didn’t, well, I did at least write down the truth that still speaks to me 26 years later: I was a young man in love, a foolish and pointless and selfish love, and yet nevertheless, one that burned like fire….

.png)