Key Points and Summary – The Eurofighter Typhoon is a masterpiece of fourth-generation engineering, a powerful and agile dogfighter that represents the pinnacle of conventional air superiority.

-However, it is an exquisite evolution of an obsolete paradigm. In the modern era, it is completely outmatched by the revolutionary capabilities of American fifth-generation stealth fighters.

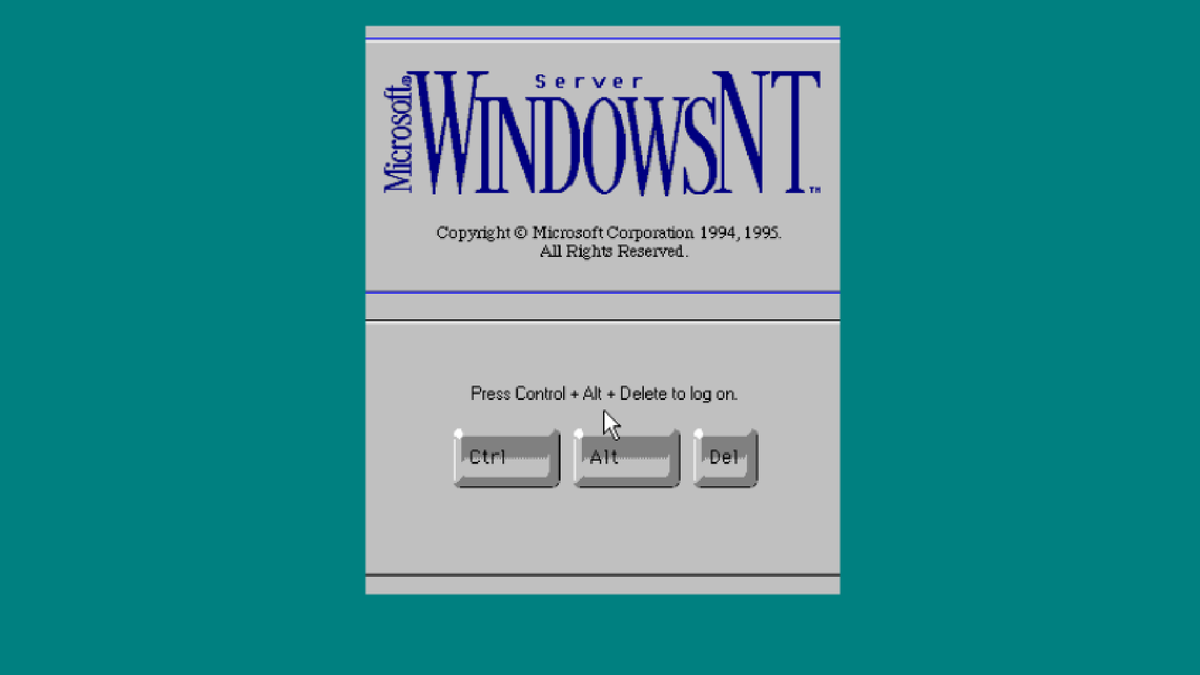

A UK Typhoon flies above the Baltics on 25 May 2022. Image Credit: NATO.

-The F-22 Raptor’s “tyranny of invisibility” allows it to dominate a Typhoon before it’s ever detected, while the F-35’s role as a networked “quarterback in the sky” places it in a different strategic league altogether.

The Eurofighter Typhoon Will Never Be a Stealth Fighter

In the unforgiving calculus of modern air combat, few aircraft can match the raw, visceral power of the Eurofighter Typhoon. It is a masterpiece of aerodynamic design, a thoroughbred fighter built for speed, agility, and overwhelming firepower.

With its twin EJ200 engines pushing it beyond Mach 2 and its canard-delta wing configuration giving it breathtaking maneuverability, the Typhoon is arguably the pinnacle of fourth-generation fighter technology. It is, without question, a king of the skies.

But in the rapidly evolving battlespace of the 21st century, being a king is no longer enough.

The advent of true stealth has created a new pantheon of aerial gods, and in that pantheon, America’s F-22 Raptor and F-35 Lightning II reign supreme.

Take it from me: comparing the Typhoon to these fifth-generation platforms is to misunderstand the fundamental revolution that has taken place.

The Typhoon is an exquisite evolution of a well-established paradigm, whereas the F-22 and F-35 represent a complete and total departure from it.

While the Eurofighter is a deadly fencer, the F-22 and F-35 are invisible assassins, and in a fight for survival, the difference is absolute.

The Apex of a Bygone Era

To be clear, underestimating the Eurofighter Typhoon would be a fatal mistake in almost any combat scenario.

The aircraft is a triumph of European engineering, a machine purpose-built to dominate a traditional air superiority battle. Its performance is nothing short of spectacular.

The Typhoon possesses a thrust-to-weight ratio that enables it to climb like a rocket and sustain high-G turns that would tear apart lesser airframes. In a close-range, within-visual-range dogfight, an experienced Typhoon pilot can be a match for nearly any opponent.

Its avionics are equally impressive. The Eurofighter Typhoon is equipped with a powerful Captor-E AESA radar, a Pirate infrared search-and-track (IRST) system, and a sophisticated defensive aids suite. When linked together, these systems provide the pilot with excellent situational awareness.

Armed with a potent mix of Meteor and AMRAAM beyond-visual-range missiles and the lethal ASRAAM for close-in encounters, the Typhoon is a formidable weapons platform. In any conflict against a third-generation or early fourth-generation adversary, the Typhoon would sweep the skies with contemptuous ease.

It represents the absolute zenith of the fighter design philosophy that dominated the Cold War and its aftermath.

But that philosophy is now obsolete.

The Tyranny of Invisibility

The single, non-negotiable factor that separates the Typhoon from the F-22 and F-35 is stealth.

And this is not a marginal advantage; it is a fundamental, war-winning chasm in capability. The Eurofighter’s designers made efforts to reduce its radar cross-section through careful shaping and the use of radar-absorbent materials, but it is, at its core, a conventional airframe.

Its external weapons stores, prominent canards, and traditional engine nacelles are all features that light up an enemy’s radar screen.

The F-22 and F-35, by contrast, were designed from the ground up with a singular obsession: to be invisible. Their very shapes are a testament to this, with every edge aligned, every surface curved, and every antenna embedded to deflect or absorb radar waves.

They carry their entire weapons load internally, maintaining a perfectly clean, low-observable profile. The result is a radar cross-section that is orders of magnitude smaller than the Typhoon’s—reportedly the size of a metal marble for the F-22.

Let the Wargame Begin

Let’s wargame this out. A four-ship flight of Typhoons is tasked with a combat air patrol over a contested region. Miles away, a two-ship element of F-22s is on a sweep mission. The powerful Captor-E radars of the Typhoons are actively scanning the sky, but they see nothing.

The F-22 Raptors, however, detected the Typhoons from over 100 miles away. The F-22 pilots don’t even need to use their own powerful radars; they can track the Typhoons passively, correlating data between their aircraft.

The Raptor pilots calmly select their targets, open their internal weapon bay doors for a few brief seconds, and launch a volley of AMRAAM missiles. The missiles scream towards their targets on a trajectory fed to them by the F-22s.

The Typhoon pilots’ first indication that they are under attack comes when their radar warning receivers scream in protest—seconds before impact. The engagement is over before the Eurofighter Typhoon pilots ever knew they were in a fight.

This isn’t a hypothetical; it is the brutal reality of stealth warfare. The ability to see first, shoot first, and kill first is the ultimate trump card, and it is a card the Typhoon simply does not hold.

The All-Seeing Eye: A Network in the Sky

If the F-22’s advantage is its unmatched combination of stealth and kinematic performance, the F-35’s is its role as a revolutionary information hub.

While the Typhoon’s sensors are excellent, they exist primarily to serve the individual aircraft. The F-35’s sensors exist to serve the entire network.

The F-35’s sensor fusion capability is what truly sets it apart. It hoovers up data from its AESA radar, its Distributed Aperture System (DAS), and its Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS), and fuses it into a single, coherent picture of the battlespace.

But its most powerful ability is to then share that picture with every other friendly asset in the area—other aircraft, ships at sea, and troops on the ground.

Imagine a scenario where an F-35 detects a modern, integrated air defense system. The F-35 pilot doesn’t need to attack it. Instead, they can use their sensors to precisely geolocate the enemy radars and launchers and then securely transmit that targeting data to a Royal Navy Type 45 destroyer offshore.

The destroyer, using the F-35’s real-time data, can launch a cruise missile to destroy the threat from hundreds of miles away. The F-35, in this instance, acts not as a fighter, but as the forward eyes and brain of the entire joint force.

Why the Eurofighter Typhoon Is Headed Into the History Books

The Eurofighter Typhoon, for all its strengths, cannot do this. It is a node designed to fight within its own network, but it is not the all-seeing quarterback that can direct the entire team. This network-centric capability, combined with its own potent stealth, makes the F-35 a strategic weapon system, while the Typhoon remains a superb, but ultimately tactical, asset.

The Eurofighter Typhoon is a magnificent fighting machine, a testament to what can be achieved with a conventional airframe pushed to its absolute limits. But it is a platform that answers the questions of the last war.

The F-22 and F-35 answer the questions of the next one.

In the lethal arena of great-power competition, where seeing without being seen is the difference between life and death, the advantage does not go to the most agile fencer. It goes to the invisible stealth warplane.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

More Military

The U.S. Navy’s ‘Achilles Heel’: China’s Underwater Drones

The F-35 Has a ‘5-Year Late’ Problem

X-37B: Russia Thinks This is a Space Bomber

.png)