Today’s internet is arguably better than it’s ever been. Yet there are significant privacy and security concerns that, despite best efforts, only seem to be getting worse.

Today’s internet is arguably better than it’s ever been. Yet there are significant privacy and security concerns that, despite best efforts, only seem to be getting worse.

Calls for governments to get much more involved carry the not insignificant risk of them doing just that. Not necessarily to tackle the issues that led to the cordial invitation, of course, but when blocking and access restrictions are heavily promoted as the solution to one problem, suddenly everyone has a problem. Governments looking for solutions unsurprisingly have many times more.

The Normalization of Blocking

A little over fifteen years ago, there wasn’t much appetite for online blocking, at least beyond abusive images and videos, for which blocking still receives overwhelming public support. Today it doesn’t really matter if the public approves or not, site blocking is permitted almost everywhere. Whether for suppressing piracy or silencing perceived overseas propaganda, or brandished as punishment for non-compliance with local rules, the potential seems unlimited.

Yet the majority of content blocking experienced day-to-day isn’t imposed, it’s a personal choice. Most browsers have an option to block popups, for example. Blocking intrusive advertising is increasingly popular too, since without some type of defense, any veneer of online privacy quickly heads south, taking usability with it. For many, the browser-based uBlock Origin remains the gold standard but thanks to ISPs’ site blocking efforts, running software like Pi-hole takes care of the ads and with its own DNS, simultaneously unblocks the pipes.

For those averse to tinkering under the hood, personal blocking performance is almost completely reliant on the decisions made by third-party blocklist maintainers. Make the right decisions and deploy reputable blocklists, overall things can go very well indeed. That doesn’t necessarily mean everything always goes according to plan, but with the right approach, getting back on track is simplicity itself.

Blocklists Always Contain Errors

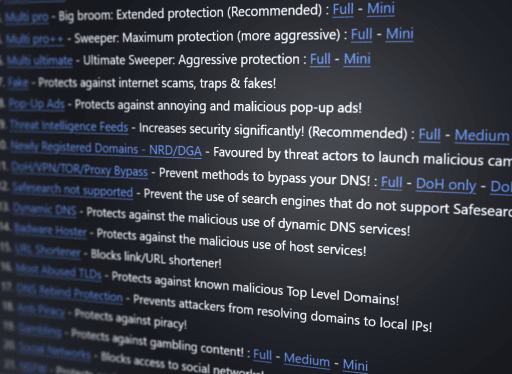

The standard lists bundled with uBlock Origin and Pi-hole are generally perceived as very good. Indeed, many view uBlock as an indispensable first line of defense against the endless appearance of malicious ads. On GitHub, all kinds of DNS blocklists are available from Hagezi’s repo, all with a common and genuine mission to keep the internet as ‘clean’ and as safe as possible.

Essentially a one-man labor of love crammed into his spare time, by many accounts Hagezi’s main lists strike a fair balance between blocking unwanted trackers and not breaking websites, which for most people is the sweet spot. For those with more specific needs, there’s no shortage of choice.

The threat intelligence-led blocklist has been used here without any issues, likewise the feed for NRDs (newly registered domains) which often contains new streaming site domains, purchased as replacements in the wake of anti-piracy blocking. Others clearly have specific goals in mind, one in particular.

The ‘Anti Piracy – Protects Against Piracy!’ Blocklist

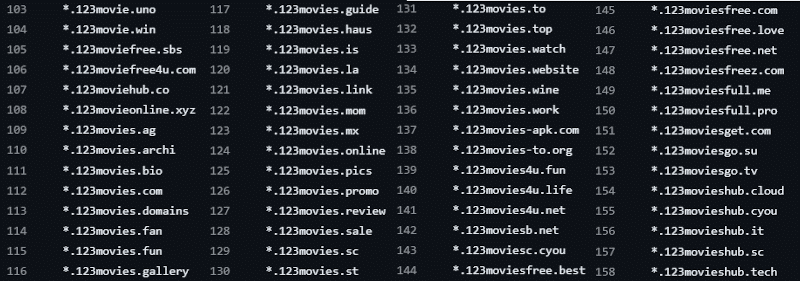

This blocklist contains over 11,000 entries, in theory blocking access to just as many pirate sites. In practice, it may block a few thousand but since domains come and go quickly, only well-funded anti-piracy groups have the necessary resources to stay anywhere near up to date, and the list naturally reflects that.

No third-party list will ever be comprehensive, and this one makes no claims to the contrary. Indeed, a disclaimer concerning all lists notes that the ultimate responsibility for using or not using a blocklist lies with the user. We completely agree, and we’ll return to that in just a moment.

The fact that many domains on the list today fell out of action a decade or more ago, presents issues. These issues are not unique to this blocklist; they also apply to any region where enthusiasm for pirate site blocking isn’t matched by corresponding unblocking when domains are repurposed.

The key differences deserve early emphasis: Pirate site blocking lists are imposed and either fully closed or open to limited scrutiny. Hagezi’s blocklists are free, voluntary, and transparent. While that means errors get pointed out (see below), that’s what gives open source its strength.

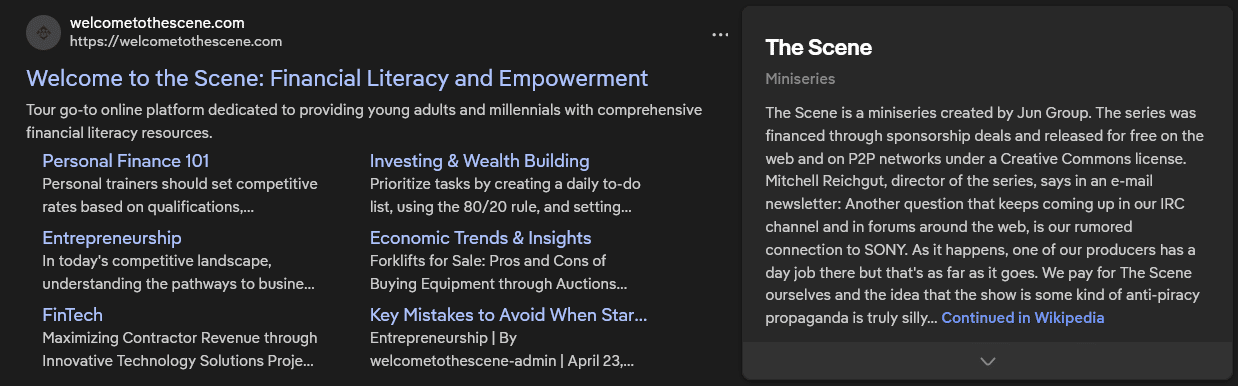

Welcometothescene.com was home to The Scene, a drama miniseries set around the topic of piracy. Created by Jun Group, the show was free to watch online, including on peer-to-peer networks, under a Creative Commons license. Released to a pre-YouTube audience in 2004, the last episode aired 20 years ago.

Long since repurposed, the domain appears both dead and alive in DuckDuckGo’s search results, and very much alive in the Anti-Piracy Blocklist.

How the domain got onto the anti-piracy blocklist is anyone’s guess, likewise why it’s somehow still there today. Other problematic entries are more current and at times, quite puzzling too.

A Few Examples

We’ve highlighted a few obvious blunders below, but the context means that when compared to similar blunders made elsewhere, these are much less serious. Mistakes are inevitable, yet transparency and the ability to put things right make a world of difference.

Open Source Projects

torrent.fedoraproject.org | torrent.ubuntu.com | fosstorrents.com | tracker.parrotlinux.org | tracker.parrotsec.org | Webtorrent.io | Instant.io

Free Music / Independent Artists / Pro-Sharing Bands

Jamendo.com | bt.etree.org

Anti-Piracy | Transparency Database | Piracy News

Alliance4Creativity.com | Lumendatabase.org | Torrentfreak.com

Government | Satire

Parliamentlive.tv | Southparkstudios.com

These issues shouldn’t detract from the quality found elsewhere in the project, where most of the attention is focused. While an erroneously blocked domain is still one too many, the open nature of these blocklists is undoubtedly one of the most important things to consider when weighing the pros and cons of any kind of content blocking.

Try not to spend too much time looking, small sections like this are entirely accurate but seriously headache-inducing.

Transparency, Accountability, and the Future of Site-Blocking

With absolutely no charge to the end user, Hagezi’s entirely open approach allows the individual to make their own choices about what happens on their networks and on their machines. Some errors will exist, they always do, so if anyone feels that a blocklist isn’t for them, so be it – nobody is being forced to do anything they don’t want to.

It’s about personal choice and striking a balance between the expected end result and the likelihood that it won’t ever be perfect, but probably good enough. And when things do go wrong, the person responsible is always around.

Formal anti-piracy blocking regimes, on the other hand, are mandatory for everyone within their increasingly broad jurisdictions. In most countries they are the antithesis of open source, despite having a direct effect on the majority of internet connections.

There’s no element of personal choice, and any balancing exercise involves someone else’s vision of a good end result. It won’t ever be perfect, but “probably good enough” takes on different light when things go wrong in this context.

Opacity as a Feature

Overblocking is not subject to public reporting and since members of the public have no direct access to blocklists, errors can’t be caught early or even caught at all. For victims of overblocking seeking answers, the almost impossible challenge is to a) prove it b) find out who’s responsible c) report it to the body set up to deal with overblocking and d) come to terms with the reality that the system protects rightsholders and ISPs, period.

If a court authorizes blocking, all parties point to each other and ultimately back to the court in the event of overblocking; bodies to deal with overblocking don’t exist, because effectively, overblocking itself doesn’t exist. That’s clearly evidenced by the lack of complaints, despite that being directly attributable to reporting opacity.

The lack of transparency is often explained as a necessary component of site-blocking strategy, in that secrecy prevents site operators from knowing that their domains are being blocked. The idea that they don’t already know only makes sense if the impact was too limited to notice. In any event, transparency with a 24-hour delay would be sufficient for the public record but unlike the imposition of secret blocklists, publication isn’t mandatory.

While Hagezi’s lists are open source and offer significant benefits for those who choose to use them, company records are proprietary. This is the future of site-blocking and the realization that it won’t arrive tomorrow, requires acceptance of a difficult truth:

For the last 15 years, it always arrived yesterday.

.png)