Uncaged

As wildlife advocates fight to free the last captives of Vietnam’s bile farms, rescued bears find dignity in the country’s sanctuaries.

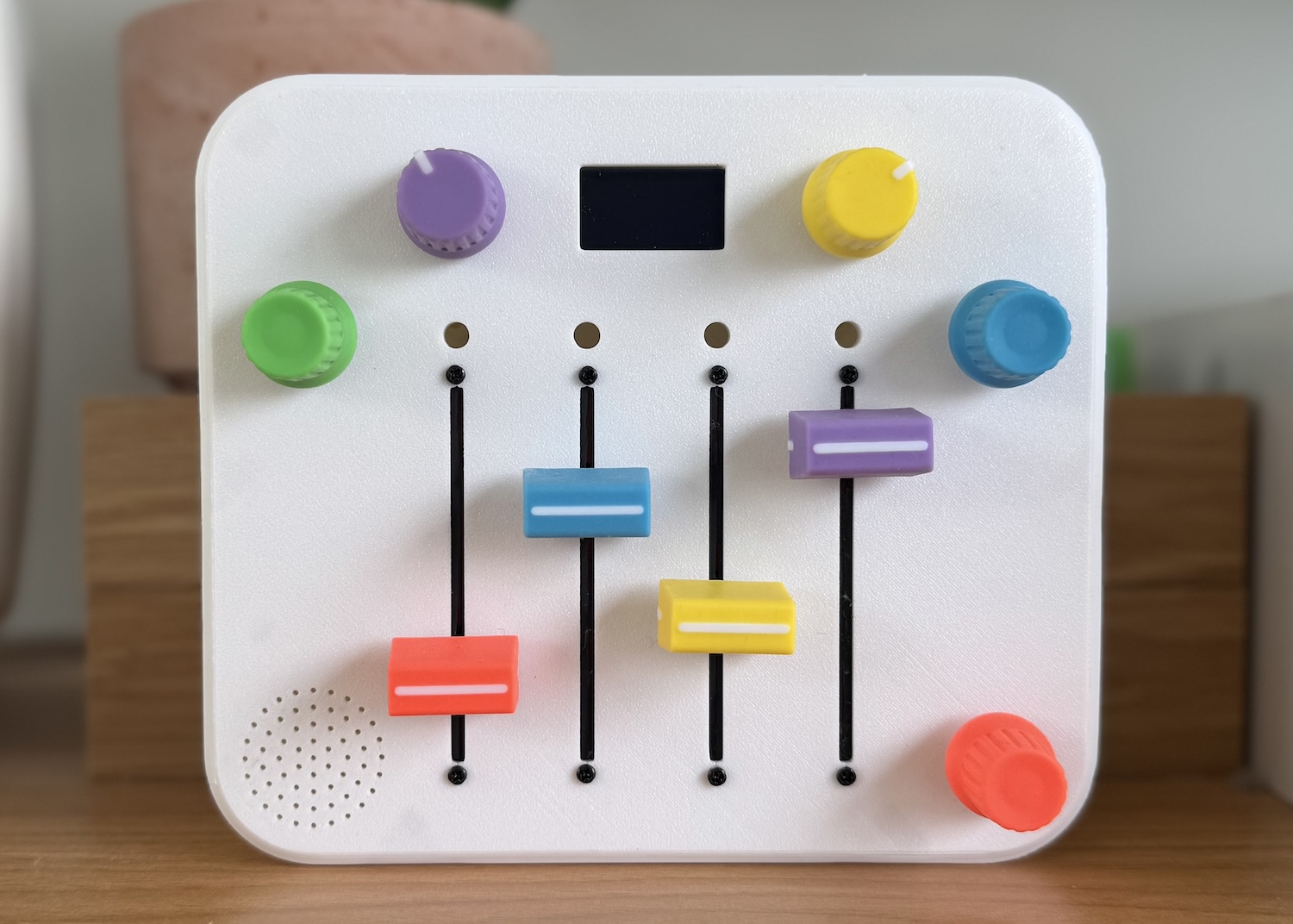

Chinh enjoys the outdoors at Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh. Photo by Jeremy Lamberton / Four Paws Viet.

Ryley Graham

IN MAY OF 2024, in the Vietnamese province of Binh Duong, an Asiatic black bear named Chinh stepped into the full light of day for perhaps the first time in 20 years. Suspected to have been captured as a cub, Chinh was one of 15 bears living in a small shed behind a house just north of Ho Chi Minh City. Each bear lived in a cage scarcely bigger than their own body, the pens placed just close enough for the bears to see and smell each other but too far to reach one another’s outstretched paws. Over the preceding five years, each of Chinh’s 14 cellmates had been rescued. He was the last one left.

Jeremy Lamberton, communications manager for Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh, where Chinh was being relocated, was among those present on the hot spring day of Chinh’s rescue. So were the local authorities and his owner.

“Chinh had to watch 14 other bears be rescued,” said Lamberton. “He belonged to a different farmer than the other bears, so that was an excruciating wait for all. I was really grateful when we heard, finally, that they were willing to voluntarily transfer us the bear. It meant the closing of another bear farm.”

While the handover day went smoothly, taking only a matter of hours, Chinh’s rescue had been a long time coming. Like thousands of Asiatic black bears, Chinh spent years subjected to the brutal conditions of bear bile farming, a practice where bears are kept in captivity in order to routinely extract their bile, which is used in traditional Asian medicine. His release was the hard-fought result of a decades-long crackdown on the industry in Vietnam.

“Chinh spent years subjected to the brutal conditions of bear bile farming, a practice where bears are kept in captivity in order to routinely extract their bile.”

After cooling Chinh down with a shower, the rescue team loaded him gently onto a truck, where an animal manager and veterinarian joined him for the two-day drive north to his new home at the sanctuary in Ninh Binh province. One of four in Vietnam, the sanctuary was founded in 2017 to provide a home for bears, like Chinh, rescued from now-illegal bile farms.

As they settled into the drive, his caretakers gave him morning glory to snack on, a natural food for wild Asiatic black bears and a deviation from his longtime diet of rice porridge, as well as bamboo sticks to play with. These were the first whiffs of his new life, marking the end of years of harsh treatment in an industry that experts hope is reaching its conclusion.

THE MEDICINAL USE of bear bile — a digestive fluid produced by a bear’s liver and stored in the gallbladder — stretches back millennia. The first mention of its use dates to 659 A.D., in what is considered the first pharmacopoeia in China. In Traditional Chinese Medicine — which is used in numerous East Asian countries, including Vietnam, Laos, and China — it is prescribed for conditions such as inflammation and hemorrhoids. Modern investigations have proven bear bile, which is sold in powder, tonic, or pill form, is effective at treating gallstones and various liver conditions in humans because it contains high concentrations of ursodeoxycholic acid. (Now this active compound can be easily and cheaply manufactured in labs.)

Vietnam has seen a 60 percent decline in the wild bear population over the past three decades.

For generations, wild bears were killed to harvest this gold-colored liquid from their gallbladder. Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus) — also known as moon bears or white-chested bears after the white, V-shaped patch of fur on their chests — are the most commonly farmed species due to their prevalence and the high concentration of ursodeoxycholic acid in their bile. However, all East Asian bear species, including brown bears (Ursus arctos) and sun bears (Helarctos malayanus) were also targeted for the substance.

In the 1980s, entrepreneurial individuals began keeping live bears in captivity in order to harvest bile repeatedly throughout the bear’s life. This idea of bear farming came from North Korea and quickly spread to China, where it was promoted (and government -funded) as a way to relieve pressure on wild bear populations, which were drastically declining due to hunting as well as habitat loss.

By the 1990s, a time when the Vietnamese economy was rapidly globalizing, bear bile farms began sprouting up across Vietnam. These weren’t massive government-backed operations but rather tended to be “mom and pop” farms started by poor or desperate people who heard it was a way to make money. Douglas Hendrie, director of law enforcement operations for the wildlife protection organization Education for Nature Vietnam, remembers this cruel practice taking off.

“Around then Vietnam started exporting a lot of their natural resources to China, which was the only buyer in the region with much money at the time,” Hendrie says. “And then as the economy developed and more Vietnamese people had money in their pockets, they could afford medicinal wildlife products like bear bile too.”

As the industry took root in Vietnam, it took a steep toll on wild bear populations. Every spring, wild mother bears were killed and their cubs captured and sold to bile farms. This poaching, combined with deforestation, decimated the wild Asiatic black bear population in Vietnam. Though formal studies are scarce, it is estimated that Vietnam has seen a 60 percent decline in the wild bear population over the past three decades. By 2005, there were roughly 4,300 captive bears held in small cages in Vietnamese sheds, yards, and basements, representing nearly 20 percent of the over 20,000 captive bears across the Asian continent.

Bile harvesting methods vary, from the old technique of performing rudimentary surgeries to the practice still used today in China of implanting a permanent stent to continuously siphon bile. All the extraction methods are painful and cause long-term health problems. In Vietnam, for bears like Chinh, a long needle is usually inserted into the gallbladder every few months. This creates repeated chances of introducing bacterial infections to the bear’s organs.

Bile bear farms generally keep bears in cages that are hardly bigger than their bodies. Photos by Wildlife in Trade.

“Chinh had a chronic bacterial infection of his gallbladder associated with bile harvesting,” says Lesley Halter-Goelkel, a veterinarian with Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh. “The bacterium we isolated is resistant to antibiotics. We had to surgically remove the gallbladder to stop the infection, chronic pain, and secondary diseases. Our team put in a lot of effort to get Chinh to a point where he can finally enjoy a pain-free life.”

AFTER A TWO-DAY journey north to Ninh Binh, Chinh arrived at the bear sanctuary after dark. Half-a-dozen staff greeted the truck and carefully unloaded his transport cage. Come morning, the light would reveal a complex with over five hectares of green space nestled amidst northern Vietnam’s famous karst mountains. If one stood on these mountains and looked down, they’d see the area divided into a patchwork of four outdoor enclosures, each connected to several bear houses or private indoor dens for individual bears. The sanctuary, established in 2017 by Austrian animal welfare organization Four Paws, currently houses 46 bears.

To ensure a comfortable transition and protect other bears from diseases, Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh has clear protocols for introducing new rescue bears like Chinh. Before they can enter a main enclosure, they spend 30 days in a smaller, private indoor quarantine house. During this time, veterinarians assess them for the typical injuries of bile farming. These might include liver and gallbladder diseases, skin infections, severe claw overgrowth, and dental problems from years of trying to chew through the bars of their cages. Malnutrition and dehydration are also foremost on caretakers’ minds, as bears are often underfed to prompt their bodies to produce more bile.

Veterinarians also use this quarantine time to assess their specific needs and perform any procedures they might need to improve the bears’ longevity and quality of life. Teo, who was among the bears rescued from the same farm before Chinh, needed an eye removed when he arrived at the sanctuary in 2022. Nhi Nho, the first bear rescued by Four Paws in 2017, was missing her front paws. By observing her mobility in quarantine, caretakers could prepare her future enclosure to meet her needs.

All bear arrivals are celebrated at the sanctuary, but Chinh’s was especially anticipated. His rescue was an indicator that the tide had truly turned against bear bile farming in the country.

The Vietnamese government outlawed bile bear farming back in 2005 and required people to register and microchip captured bears. Under this law, the transfer, sale, or acquisition of any new bears results in confiscation of the animal. But since there were no rescue centers in the country at the time and the bears could not be released into the wild, owners were allowed to keep their bears if they agreed not to extract bile.

World Animal Protection, a London-based global nonprofit aimed at ending animal suffering, agreed to help implement the new law, and by 2006 the group had helped to microchip the about 300 bears being held in farms across the country at the time.

After bears are rescued, veterinarians assess their specific needs and perform any procedures they might need to improve the bears’ longevity and quality of life. Photo courtesy of British Veterinary Association.

The organization partnered with a local group, Education for Nature Vietnam, which focused on bile demand reduction and prosecution of those breaking these new laws. Education for Nature Vietnam also started a wildlife hotline where locals could call and report trafficking activity, and it helped law enforcement, from local police to the forestry department, understand and implement the country’s evolving wildlife laws, explains Bui Thi Ha, its director of policy.

“For the local police, we may need to provide them, for example, with the legal protection status of the bear, or perhaps inform them of the punishment rank for the type of crime,” Ha says. Once bear sanctuaries were set up in the country, the organization also began to “help connect the police with the appropriate rescue center to send the bear,” Ha adds.

That work started in 2008, when the animal welfare organization Free the Bears opened the first bear sanctuary in Vietnam, just north of Ho Chi Minh City. This made it possible for law enforcement to confiscate bears that were not being cared for in accordance with the new laws.

“[Bears] are incredibly resilient to bad conditions. And that’s a curse for them, because they manage to survive in these farms for way too long.”

Of course, illegal bear trafficking didn’t cease overnight. In the 2010s, there were still around 1,000 former bile bears, like Chinh, who could be lawfully kept captive until death. In 2016, a decade after bile farming was made illegal, Free the Bears conducted interviews with bear farmers in provinces with the highest continued captive bear population. Ninety-five percent of interviewees confessed to regularly extracting bile. However, the overall number of captive bears in Vietnam fell steadily over the subsequent years, and further gains followed.

In 2015, Animals Asia signed an agreement with the Vietnamese Traditional Medicine Association to end bear bile prescriptions, and in 2017, the Vietnam Ministry of Forestry signed an agreement with Animals Asia to rescue all the remaining captive bears in the country. In 2018, the country finally revised its penal code to make possession and sale of a protected species, including moon bears, a criminal offense. For the first time in Vietnam, trafficking wildlife and wildlife products carried the possibility of up to 15 years in prison, a punitive risk that could potentially dissuade even seasoned traffickers. Though this sentence has yet to be administered for a bear-related incident, Hendrie says that the threat has helped to further curb bear poaching.

But for the bears who were already behind bars when the ban was implemented, the future remained at the whims of the humans just outside of their rusting cages.

“I’ve been working with bears for such a long time, and they are intelligent, sentient beings,” says Jan Schmidt-Burbach, director of wildlife research and veterinary expertise at World Animal Protection. “They are incredibly resilient to bad conditions. And that’s a curse for them, because they manage to survive in these farms for way too long.”

A MONTH AFTER his rescue, Chinh was finally released into one of the full-sized bear enclosures, but with a fence giving him his own private section to allow time for adjustment to this new environment. Many bears at Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh live communally, but as the sanctuary’s ethos involves giving bears the choice, they are only grouped if they demonstrate interest. Like the rest of the enclosure, Chinh’s latest space was filled with plants and play structures. Slowly, he began exploring. He pawed at “enrichment materials,” mechanisms specially created by caretakers to make food-finding more entertaining. He shook a pole to knock snacks loose, and explored a carved-out log for stashed treats.

For Chinh and many other rescued bears, adjusting to this new life with more freedom isn’t always simple. Even in their outdoor enclosures designed to reflect the wild, they can struggle to enjoy the breadth of their options — in addition to the massive physical toll bile farming takes on bears, the practice leaves mental and emotional wounds as well. These manifest in what veterinarians refer to as abnormal repetitive behaviors: trauma responses that result from years of stress, absence of stimulus, frustration, and pain in cages. Some spend hours on end rocking their heads back and forth, while others display lethargy. Even in the space of his outdoor enclosure, Chinh would sometimes pace endlessly in circles, as though still confined to a tiny cage.

Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh, established in 2017 by Four Paws, now houses 46 rescued bears. The nonprofit continues to work with other animal rights groups and the Vietnamese government to free the last remaining captive bears in the country. Photo by Chris Humphrey / Dpa picture alliance.

But over time, Chinh began building a relationship with his caretaker — all bears at the sanctuary are assigned a caretaker who learns their individual needs — and adjusting to his new routine. Three times a day, bears are called to their dens so that food in the outdoor enclosure can be replaced. While caretakers replenish the food, as well as their enrichment materials, Chinh and his fellow bears receive any necessary medications, delivered in banana chunks to disguise the taste, from the comfort of their den hammocks and straw beds.

“Then they are let outside to forage,” explains Emily Lloyd, an animal manager at the sanctuary. “Usually after they are done foraging for food, they will play with each other, maybe swim, or find somewhere comfortable to sleep.”

Despite all the care showered on them, some bears are not able to express natural behaviors, and some even injure themselves, Halter-Goelker says. The staff at Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh are painfully aware that rescue doesn’t necessarily mean an end to all suffering.

“I try not to project ‘happiness’ onto them as some kind of destination,” Lamberton says. “But certainly our enclosures give greater privacy and the dignity to exhibit more natural bear behaviors. The time to rehabilitate in a species-appropriate environment is something all farmed bears deserve.”

AT THE TIME of publication, there are 157 captive bears in Vietnam, 79 of whom are held in the capital city of Hanoi. Another 332 bears are living in Vietnam’s four sanctuaries. As for the specific fates of the thousands of other bears recorded 20 years ago, the details are largely lost to history. But the tragic truth, according to Hendrie of Education for Nature Vietnam, is that the majority were slaughtered when their owners aged or it became too expensive to keep them without harvesting bile.

While those numbers are hard to stomach, the phase-out of the industry means that today, cubs are rarely captured from the wild. Indeed, Hendrie says that the number of wild bears caught in Vietnam has declined significantly since bile farming was made illegal. In the years after the 2005 laws were enacted, his organization used to confiscate a dozen trafficked cubs a year. Nowadays, some years pass without seeing any. In November of 2024, conservationists across the country celebrated when a wild bear was spotted on camera in central Vietnam — a rare and heartening moment for those who have been tracking the wild population.

“Sanctuaries have already prepared enough space to take every single captive bear in the country through their final days.”

Demand for bear bile is decreasing in Vietnam as well, with younger generations more inclined to move on from wildlife products. Ha says that over the years, the public’s utilization of Education for Nature Vietnam’s wildlife crime hotline has continued to increase, a potential indicator that the Vietnamese public is increasingly concerned about wildlife crimes. In 2014, the hotline received 557 reported cases, while by 2024 that number jumped to 1,915 cases.

For those who still seek similar treatments to bear bile, Animals Asia runs an education campaign with local schools in regions that remain strongholds for the industry, helping students to grow herbs that are proven to contain the same healing properties as bear bile. The nonprofit has also released a recipe book with herbal alternatives. There are over 30 known herbal and synthetic alternative remedies to bear bile that, although they don’t contain ursodeoxycholic acid, can be applied to the same ailments. These include cape jasmine (Gardenia jasminoides), effective at treating inflammation, and green chiretta (Andrographis paniculata), long used to treat arthritis.

When the bile bear farming industry was thriving, wild mother bears were frequently killed and their cubs captured and sold to bile farms. Today, cubs are rarely captured in the wild. Photo by Tontan Travel.

There’s still work to be done, of course. China, where the practice is still legal, has a thriving bear bile industry. Animal rights advocates estimate over 10,000 bears are held captive there today. While other countries like South Korea have also cracked down on the industry (its bile industry is projected to end next year), bears remain in captivity there, too. And across the continent, Asiatic black bears are still listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List.

“[Bear bile farming] is going to end, but how it ends will be more important.”

In Vietnam, which might be approaching the day when it can say it no longer has any bear farms, organizations like Hendrie’s continue lobbying for the freedom of the remaining 157 bears. One of their main campaigns now is to convince farmers in the Phuc Tho district of Hanoi, where Hendrie says some of the most stubborn traffickers are still holding onto their bears, to relinquish them. Sanctuaries have already prepared enough space to take every single captive bear in the country through their final days.

“[Bear bile farming] is going to end, but how it ends will be more important. We, as humans, need to give these bears a better rest of their lives,” Ha says. “And for me, from a policy standpoint, the fact that we are getting close demonstrates the government’s commitment to do something meaningful about this problem.”

TWO MONTHS AFTER first leaving the quarantine house to explore his private enclosure at Bear Sanctuary Ninh Binh, Chinh was socialized with two other bears, Tai and Tinh, and now cohabitates with them. The three can often be seen sparring together, tumbling playfully until it’s unclear where one animal ends and the other begins.

Sniffing around his enclosure, he can smell the pumpkin and shrimp paste tenderly stashed for him by caretakers. On the Ninh Binh breeze, perhaps he can smell some of his former companions across the sanctuary, freed from that shed in Binh Duong. Under his paws, finally, is the scent of grass, planted to resemble that of the far-off wild place he barely got the chance to roam.

Ryley Graham

Ryley Graham is a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn, New York. Her work, spanning topics from food history to wildlife conservation, has appeared in publications such as Smithsonian Magazine and National Geographic.

You Make Our Work Possible

You Make Our Work Possible

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

Subscribe Now

Get four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.

.png)