Programming, philosophy, pedaling.

Jun 11, 2025 Tags: security

TL;DR: GitHub Actions provides a policy mechanism for limiting the kinds of actions and reusable workflows that can be used within a repository, organization, or entire enterprise. Unfortunately, this mechanism is trivial to bypass. GitHub has told me that they don’t consider this a security issue (I disagree), so I’m publishing this post as-is.

Background

GitHub Actions is GitHub’s CI/CD offering. I’m a big fan of it, despite its spotty security track record.

Because a CI/CD offering is essentially arbitrary code execution as a service, users are expected to be careful about what they allow to run in their workflows, especially privileged workflows that have access to secrets and/or can modify the repository itself. That, in effect, means that users need to be careful about what actions and reusable workflows they trust.

Like with other open source ecosystems, downstream consumers (i.e., users of GitHub Actions) retrieve their components (i.e., action definitions) from an essentially open index (the “Actions Marketplace”1).

To establish trust in those components, downstream users perform all of the normal fuzzy heuristics: they look at the number of stars, the number of other user, recency of activity, whether the user/organization is a “good” one, and so forth.

Unfortunately, this isn’t good enough along two dimensions:

-

Even actions that satisfy these heuristics can be compromised. They’re heuristics after all, not verifiable assertions of quality or trustworthiness.

The recent tj-actions attack typifies this: even popular, widely-used actions are themselves software components, with their own supply chains (and CI/CD setups).

-

This kind of acceptance scheme just doesn’t scale, both in terms of human effort and system complexity: complex CI/CD setups can have dozens (or hundreds) of workflows, each of which can contain dozens (or hundreds) of jobs that in turn employ actions and reusable workflows.

These sorts of large setups don’t necessarily have a single owner (or even a single team) responsible for gating admission and preventing a the introduction of unvetted actions and reusable workflows.

GitHub Actions policies

The problem (as stated above) is best solved by eliminating the failure mode itself: rather than giving the system’s committers the ability to introduce new actions and reusable workflows without sufficient review, the system should prevent them from doing so in the first place.

To their credit, GitHub understands this! They have a feature called “Actions policies2” that does exactly this. From the Manage GitHub Actions settings documentation:

You can restrict workflows to use actions and reusable workflows in specific organizations and repositories. Specified actions cannot be set to more than 1000. (sic)

To restrict access to specific tags or commit SHAs of an action or reusable workflow, use the same syntax used in the workflow to select the action or reusable workflow.

-

For an action, the syntax is OWNER/REPOSITORY@TAG-OR-SHA. For example, use actions/[email protected] to select a tag or actions/javascript-action@a824008085750b8e136effc585c3cd6082bd575f to select a SHA. For more information, see Using pre-written building blocks in your workflow.

-

For a reusable workflow, the syntax is OWNER/REPOSITORY/PATH/FILENAME@TAG-OR-SHA. For example, octo-org/another-repo/.github/workflows/workflow.yml@v1. For more information, see Reusing workflows.

You can use the * wildcard character to match patterns. For example, to allow all actions and reusable workflows in organizations that start with space-org, you can specify space-org*/*. To allow all actions and reusable workflows in repositories that start with octocat, you can use */octocat**@*. For more information about using the * wildcard, see Workflow syntax for GitHub Actions.

Use , to separate patterns. For example, to allow octocat and octokit, you can specify octocat/*, octokit/*.

GitHub also provides special “preset” cases for this functionality, such as allowing only actions and reusable workflows that belong to the same organization namespace as the repository itself. Here’s what that looks like on a dummy organization and repository of mine:

…and here’s what happens when I try to violate that policy, e.g. by using actions/checkout@v4 in a workflow:

This is fantastic, except that it’s trivial to bypass. Let’s see how.

Bypassing policies

To understand how we’re going to bypass this, we need to understand a few of the building blocks underneath actions and reusable workflows.

In particular:

- Actions and reusable workflows share the same namespace as the rest of GitHub, i.e. owner/repo3;

- When a user writes something like uses: actions/checkout@v4 in a workflow, GitHub resolves that reference to mean “the action.yml file defined at tag v4 in the actions/checkout repository”;

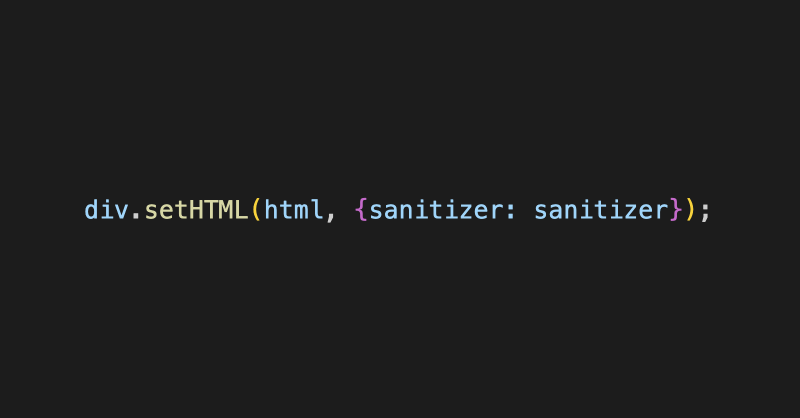

- uses: keywords can also refer to relative paths on the runner itself. For example, uses: ./ runs the step with the action.yml in the current directory.

- Relative paths from the runner are not inherently part of the repository state itself: the runner is can contain any state introduced by previous steps within the same job.

These four aspects of GitHub Actions compose together into the world’s dumbest policy bypass: instead of doing uses: actions/checkout@v4, the user can git clone (or otherwise fetch) the actions/checkout repository into the runner’s filesystem, and then use uses: ./path/to/checkout to run the very same action.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | on: [push, pull_request] jobs: test: runs-on: ubuntu-latest steps: - run: | mkdir -p ./tmp git clone https://github.com/actions/checkout.git ./tmp/checkout - uses: ./tmp/checkout with: repository: woodruffw/gha-hazmat path: gha-hazmat - run: ls && pwd - run: ls tmp/checkout |

(The actual with: block of the uses: ./tmp/checkout step is inconsequential — I just used that repository for the demo, but anything would work.)

And naturally, it works just fine:

Fixing it?

The fix for this bypass is simple, if potentially somewhat painful: GitHub Actions could consider “local” uses: references to be another category for the purpose of policies, and reject them whenever the policy doesn’t permit them.

This would seal off the entire problem, since uses: ./foo would just stop working. The downside is that it would potentially break existing users of policies who also use local actions and reusable workflows, assuming there are significant numbers of them4.

The other option would be to leave it the way it is, but explicitly document local uses: references as a limitation of this policy mechanism. I honestly think this would be perfectly fine; what matters is that users5 are informed of a feature’s limitations, not necessarily that the feature lacks limitations.

Does this matter?

First, I’ll couch this again: this is not exactly fancy stuff. It’s a very dumb bypass, and I don’t think it’s critical by any means.

At the same time, I think this matters a great deal: ineffective policy mechanisms are worse than missing policy mechanisms, because they provide all of the feeling of security through compliance while actually incentivizing malicious forms of compliance.

In this case, the maliciously complying party is almost certainly a developer just trying to get their job done: like most other developers who encounter an inscrutable policy restriction, they will try to hack around it such that the policy is satisfied in name only.

For that reason alone I think GitHub should fix this bypass, either by actually fixing it or at least documenting its limitations. Without either of those, projects and organizations are likely to mistakenly believe that these sorts of policies provide a security boundary where none in fact exists.

.png)

![ChatGPT made me delusional [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/firefox.png)