“A tale of shakedowns, sex, and vengeance that expose[s] tensions between the church and England’s elite."

Location of the murder of John Forde, taken from the Medieval Murder Maps. Credit: Medieval Murder Maps. University of Cambridge: Institute of Criminology

In 2019, we told you about a new interactive digital "murder map" of London compiled by University of Cambridge criminologist Manuel Eisner. Drawing on data catalogued in the city coroners' rolls, the map showed the approximate location of 142 homicide cases in late medieval London. The Medieval Murder Maps project has since expanded to include maps of York and Oxford homicides, as well as podcast episodes focusing on individual cases.

It's easy to lose oneself down the rabbit hole of medieval murder for hours, filtering the killings by year, choice of weapon, and location. Think of it as a kind of 14th-century version of Clue: It was the noblewoman's hired assassins armed with daggers in the streets of Cheapside near St. Paul's Cathedral. And that's just the juiciest of the various cases described in a new paper published in the journal Criminal Law Forum.

The noblewoman was Ela Fitzpayne, wife of a knight named Sir Robert Fitzpayne, lord of Stogursey. The victim was a priest and her erstwhile lover, John Forde, who was stabbed to death in the streets of Cheapside on May 3, 1337. “We are looking at a murder commissioned by a leading figure of the English aristocracy," said University of Cambridge criminologist Manuel Eisner, who heads the Medieval Murder Maps project. "It is planned and cold-blooded, with a family member and close associates carrying it out, all of which suggests a revenge motive."

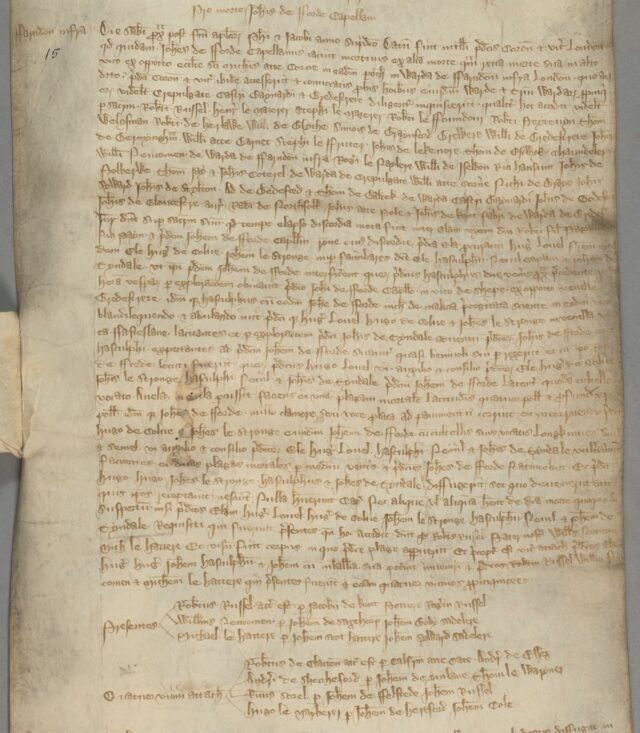

Members of the mapping project geocoded all the cases after determining approximate locations for the crime scenes. Written in Latin, the coroners' rolls are records of sudden or suspicious deaths as investigated by a jury of local men, called together by the coroner to establish facts and reach a verdict. Those records contain such relevant information as where the body was found and by whom; the nature of the wounds; the jury's verdict on cause of death; the weapon used and how much it was worth; the time, location, and witness accounts; whether the perpetrator was arrested, escaped, or sought sanctuary; and any legal measures taken.

A brazen killing

The murder of Forde was one of several premeditated revenge killings recorded in the area of Westcheap. Forde was walking on the street when another priest, Hascup Neville, caught up to him, ostensibly for a casual chat, just after Vespers but before sunset. As they approached Foster Lane, Neville's four co-conspirators attacked: Ela Fitzpayne's brother, Hugh Lovell; two of her former servants, Hugh of Colne and John Strong; and a man called John of Tindale. One of them cut Ford's throat with a 12-inch dagger, while two others stabbed him in the stomach with long fighting knives.

At the inquest, the jury identified the assassins, but that didn't result in justice. “Despite naming the killers and clear knowledge of the instigator, when it comes to pursuing the perpetrators, the jury turn a blind eye,” said Eisner. “A household of the highest nobility, and apparently no one knows where they are to bring them to trial. They claim Ela’s brother has no belongings to confiscate. All implausible. This was typical of the class-based justice of the day.”

Colne, the former servant, was eventually charged and imprisoned for the crime some five years later in 1342, but the other perpetrators essentially got away with it.

Eisner et al. uncovered additional historical records that shed more light on the complicated history and ensuing feud between the Fitzpaynes and Forde. One was an indictment in the Calendar of Patent Rolls of Edward III, detailing how Ela and her husband, Forde, and several other accomplices raided a Benedictine priory in 1321. Among other crimes, the intruders "broke [the prior's] houses, chests and gates, took away a horse, a colt and a boar... felled his trees, dug in his quarry, and carried away the stone and trees." The gang also stole 18 oxen, 30 pigs, and about 200 sheep and lambs.

There were also letters that the Archbishop of Canterbury wrote to the Bishop of Winchester. Translations of the letters are published for the first time on the project's website. The archbishop called out Ela by name for her many sins, including adultery "with knights and others, single and married, and even with clerics and holy orders," and devised a punishment. This included not wearing any gold, pearls, or precious stones and giving money to the poor and to monasteries, plus a dash of public humiliation. Ela was ordered to perform a "walk of shame"—a tamer version than Cersei's walk in Game of Thrones—every fall for seven years, carrying a four-pound wax candle to the altar of Salisbury Cathedral.

The London Archives. Inquest number 15 on 1336-7 City of London Coroner’s Rolls. Credit: The London Archives

Ela outright refused to do any of that, instead flaunting "her usual insolence." Naturally, the archbishop had no choice but to excommunicate her. But Eisner speculates that this may have festered within Ela over the ensuing years, thereby sparking her desire for vengeance on Forde—who may have confessed to his affair with Ela to avoid being prosecuted for the 1321 raid. The archbishop died in 1333, four years before Forde's murder, so Ela was clearly a formidable person with the patience and discipline to serve her revenge dish cold. Her marriage to Robert (her second husband) endured despite her seemingly constant infidelity, and she inherited his property when he died in 1354.

“Attempts to publicly humiliate Ela Fitzpayne may have been part of a political game, as the church used morality to stamp its authority on the nobility, with John Forde caught between masters,” said Eisner. “Taken together, these records suggest a tale of shakedowns, sex, and vengeance that expose tensions between the church and England’s elites, culminating in a mafia-style assassination of a fallen man of god by a gang of medieval hitmen.”

I, for one, am here for the Netflix true crime documentary on Ela Fitzpayne, “a woman in 14th century England who raided priories, openly defied the Archbishop of Canterbury, and planned the assassination of a priest," per Eisner.

The role of public spaces

The ultimate objective of the Medieval Murder Maps project is to learn more about how public spaces shaped urban violence historically, the authors said. There were some interesting initial revelations back in 2019. For instance, the murders usually occurred in public streets or squares, and Eisner identified a couple of "hot spots" with higher concentrations than other parts of London. One was that particular stretch of Cheapside running from St Mary-le-Bow church to St. Paul's Cathedral, where John Forde met his grisly end. The other was a triangular area spanning Gracechurch, Lombard, and Cornhill, radiating out from Leadenhall Market.

The perpetrators were mostly men (in only four cases were women the only suspects). As for weapons, knives and swords of varying types were the ones most frequently used, accounting for 68 percent of all the murders. The greatest risk of violent death in London was on weekends (especially Sundays), between early evening and the first few hours after curfew.

Eisner et al. have now extended their spatial analysis to include homicides committed in York and London in the 14th century with similar conclusions. Murders most often took place in markets, squares, and thoroughfares—all key nodes of medieval urban life—in the evenings or on weekends. Oxford had significantly higher murder rates than York or London and also more organized group violence, "suggestive of high levels of social disorganization and impunity." London, meanwhile, showed distinct clusters of homicides, "which reflect differences in economic and social functions," the authors wrote. "In all three cities, some homicides were committed in spaces of high visibility and symbolic significance."

Criminal Law Forum, 2025. DOI: 10.1007/s10609-025-09512-7 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

.png)

![Micrographia (1665) [pdf]](https://news.najib.digital/site/assets/img/broken.gif)