One of the issues in ticketing is that many events have much more demand for tickets than they can supply. Obviously, this is a good problem to have (better than empty halls), but it attracts certain types of bad actors trying to get as many tickets as possible in order to resell them (“ticket scalping”). While this is possible of course just by buying tickets like a regular customer, many of them use computer programs (“bots”) to enhance either their chance of claiming a ticket or their scale of operation by buying more tickets.

The naive economic solution to the problem would be raising ticket prices step by step until it is no longer attractive for scalpers to resell your ticket, because the original price of the ticket is already the maximum that people are willing to pay, creating an economic equilibrium. Most organizers, including for-profit organizations, do not want to choose this option due to ethical concerns or concerns about community building.

Therefore, whenever this topic comes up, someone quickly suggests a technical solution – usually a CAPTCHA. I believe that CAPTCHAs no longer provide any meaningful protection in this scenario. Here’s why:

We have run out of problems

CAPTCHAs were invented over 20 years ago to distinguish between human and non-human users of a website. The basic idea is this: Ask the user to solve a problem that is easy to solve for a human but hard to solve for a computer. The most popular early problem used in CAPTCHAs was text recognition, often under artificially bad conditions. This often looked like this:

These days, a state-of-the-art machine learning model is able to easily solve this problem and recognize the words. Any attempt to make the text even more unreadable will make it too hard for the average human user as well, making it unsuitable.

Around ten years ago, Google and others therefore switched to one of the problems that remained hard at the time: Image recognition. I don’t need to explain this to you, you have all clicked on way to many motorcycles yourselves:

However, in 2025, this is also no longer a challenge to computers. A modern image detection model will be able to point out the motorcycles in this screenshot faster than any human.

To make it harder, a good CAPTCHA always needs a second type of problem since we need to provide accessibility for humans who cannot see. This has always been the right thing to do, but in Europe it’s now also becoming the law. A typical choice is an audio recognition task:

Have you seen what modern speech recognition models can do? They can certainly understand audio better than any non-native speaker of most languages.

Unfortunately, I don’t see any new approaches of this type replacing the current ones. We are running out of suitable problems that humans can solve better than computers. Of course, there are still a lot of things that humans can do better than computers – but not things that all humans can do better than computers and that can be tested over the internet with a few simple clicks in a few seconds.

If AI is the problem, surely it is also the solution

What I’m saying above is not new information. That’s why people working on bot protection have moved to solutions other than having the user solve puzzles many years ago. One of these approaches is behavior analysis using machine learning.

In 2014, Google presented the one-click CAPTCHA and later, with reCAPTCHA v3, the “invisible CAPTCHA”. Similar services are offered by other companies like Cloudflare, Akamai, and others.

They rely on analyzing everything they know about you and feeding it into a large machine-learning model to compare you with behavior they know from humans and bots. That’s a clever idea, but it comes with two significant drawbacks:

First, it’s a privacy nightmare. The entire idea only works if you’re collecting a lot of data. Given the types of companies who offer this service, they most likely not only collect data about how people behave on your website, but how people behave on other websites as well. This requires the creation of extensive centralized profiles about the people visiting your site.

Second, at least in ticketing, there’s not really a good way to handle false positives. Say the model makes a wrong decision and puts an entire class of valid human users into the “bot” bucket, for example, everyone who has never visited one of the sites protected by the company before, or everyone who uses a specific assistive technology.

In some scenarios, e.g. when protecting an online forum against spam, you can place submissions with a high bot score into manual review. However, in high-demand ticketing, you need to make a binary choice: Either you sell the user a ticket, or you don’t. Risking to exclude an entire class of users is not only unethical, but also a possible legal risk.

So what do these solutions usually do? If your bot score is too high, they show you a classical CAPTCHA again. This however, as we’ve seen above, is no longer a real hurdle to bots.

Many signals are not accessibility-safe

Say we want to build a solution that is built on behavior analysis only of the user’s behavior on our site, not across half the internet. What information do we have to work with?

Fifteen years ago, bots used to be scripts that used HTTP libraries to interact with web pages. So we could look at JavaScript execution behavior, HTTP header fingerprinting, timing differences in loading resources, and similar signals. These days, bots are using real browsers that load web pages just like regular users. The bots use the APIs provided by browsers to analyze the page and control what the browser does.

Now, I’ve already mentioned that we need to build solutions in a way that are accessible to all users. This includes users who make use of assistive technology such as screen readers. And what does a screen reader do? It interacts with the browser through the APIs the browser provides to analyze the page and control what the browser does.

So all the differences we might expect between an “average user” and a bot, such as the lack of mouse movement before a button is clicked, we will also see when someone is using assistive technology (or, in this example, just a touch screen).

Proof of Work doesn’t work for ticketing

The current trend in bot prevention is using a proof of work scheme, popularized by solutions like Friendly Captcha or Anubis.

The idea between proof of work for spam protection goes back to 1997 and is quite different than the CAPTCHAs presented above. We’re no longer looking for problems that humans can solve better than computers. We’re now looking for problems that are costly for computers to solve. The typical example is brute-forcing a hash function. Any computer can do that, but – depending on the capability of the computer – it will take the computer a certain amount of time. Computing time costs power, and power costs money.

The idea is to make spamming too expensive for the spammers. If you need to spend 0.0001 € in power to access a website, a human user will probably not care. For someone who is trying to spam millions of messages or scrape the entire internet, however, it will add up to a significant total cost and the spamming or scraping might not be worth it any more.

The ethically questionable idea of burning power on useless computations (even if just a little) aside, I don’t consider this economic argument plausible for ticketing. If a spammer needs to spend 0.0001 € in power to access the site only to gain a marginal profit of 0.00005 €, they are losing money with every site access. However, if a ticket scalper needs to spend 0.0001 € in power to buy a ticket that they will later sell at a 200 € profit, this will not stop them.

The economics problem affects traditional CAPTCHAs as well

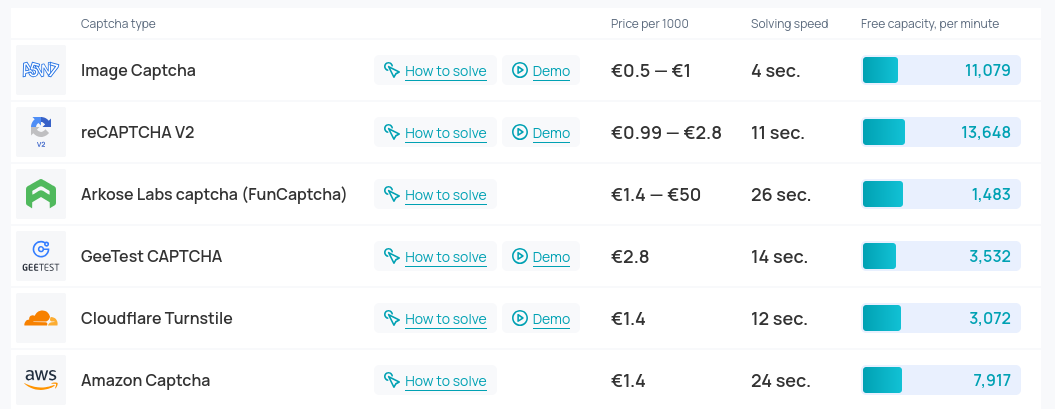

This economic argument also applies to all the traditional CAPTCHAs we’ve talked about. While modern machine learning can easily recognize characters, spoken words, or images of motorcycles, every run of the machine learning model comes at a cost. Google’s cloud vision API, for example, costs 0.0015 $ per picture for text detection and 0.00225 € for object localization.

Even if we did find new problems that are still too hard for computers, there are companies who employ gig workers in low-price countries to solve CAPTCHAs for you. It’s not hard to find CAPTCHA bypass providers that use a combination of AI and low-paid workers to solve CAPTCHAs for you at speed and very low cost:

So what’s left?

I believe that the possibility to reliably tell a bot from a human through something simple like a CAPTCHA is a thing of the past in an industry like ticketing where the financial motivation for circumvention is very high.

One tactic that can still be quite effective is limiting resale possibilities by strongly personalizing tickets, including ID card verification of at least a relevant sample of sold tickets at the event entrance. This still allows scalpers to sell something like “bot as a service” in advance of the ticket sale but limits any type of “buy-and-resell-later” schemes. Of course it also harms real buyers who want to go to a concert with a +1 but do not yet know who they will bring.

A related option is to strongly bind purchase limits to other resources that are not easy to acquire quickly in large amounts, such as allowing only X tickets per (verified) phone number or – as you will need to collect payment information for the ticket anyway – per verified credit card or verified bank account. People are able to easily get multiple phone numbers and bank accounts, but getting dozens or hundreds of them becomes a lot more effort. A sufficiently motivated bad actor will still be able to acquire many of these, but it will increase the cost involved significantly and also many possible circumvention techniques (like buying stolen credit card numbers) are significantly more illegal than solving CAPTCHAs with AI and might be beyond what at least some of the actors are ready to do.

The BAP theorem

In computer science, there is the “CAP theorem”. It states that when designing a database system, you can choose between the three properties “consistency”, “availability”, and “partition tolerance”. And while it is possible to combine two of them, it is impossible to combine all three – you always need to give one up.

I’m proposing a similar theorem for bot protection, the “BAP theorem”, stating that you can only combine two of the following three properties:

- Bot-resistance

- Accessibility

- Privacy-friendliness

The possible combinations of these properties would be:

-

BA: Bot-resistant and accessible, but not privacy-friendly. In this category we find all approaches based on heavily personalized tickets, possibly with strong identification methods. If there is a good accessibility fallback, then large-scale behaviour analysis also falls under this category.

-

BP: Bot-resistant and privacy-friendly, but not accessible. This category contains all approaches trying to use the remaining bits and pieces that are hard for AI and easy for humans, such as heavily relying on mouse movements, any puzzles involving complex user interaction, or any tricks playing with the limitations of the browser APIs.

-

AP: Accessible and privacy-friendly, but not bot-resistant. This category is easy and includes many things down to the trivial case of no protection at all, or any attempt to fight off at least very simple bots without harming the other goals.

Conclusion

Since accessibility is required by law, we’re basically left with the first or last option. As much as I hope that I’ve missed something significant, I feel the conclusion is inevitable:

Events will need to decide whether they want to protect against bots, or preserve high privacy standards. You will not be able to do both.

It remains, unfortunately, very hard to solve social problems with technology. Looking at social solutions, some have tried making ticket scalping illegal – with varying success. If your country is not on that list, lobbying for it should be part of your solution strategy – but will most likely will be a very long road to a solution.

.png)