Last week I propped my phone on the breakfast table, opened ChatGPT’s voice mode (just updated to be more lifelike), and introduced it to my kindergartener. Smiling, my child enthusiastically asked a question, the synthetic baritone said, “Good morning!”, and then proceeded to completely mispronounce his name. My kid’s face collapsed. I stepped in and corrected the model, multiple times. The bot’s voice would eagerly apologize, say they were going to get it right from now on, and continue to say it incorrectly.

My kid’s reaction to this was legitimate sadness. To many kids ChatGPT has become a fun app to chat with about wild questions or even play verbal games with. My kid being no exception, this mispronunciation came as a betrayal. Names are important (especially for a kindergartener), and so this stumble carried a tangible significance. This got me thinking; if a simple misstep by ChatGPT can cause an emotional response like this in a kid, what is more extensive usage doing to its 400 million weekly users?

This pronunciation glitch captures the a gap between what AI systems promise and what they can actually deliver today. Text-to-speech engines still stumble on uncommon names, acronyms, and anything that sits outside their phonetic training set, a limitation long documented by speech-synthesis researchers. OpenAI’s own Reddit is full of parents and teachers who watch Voice Mode butcher student roll calls and cartoon characters alike.

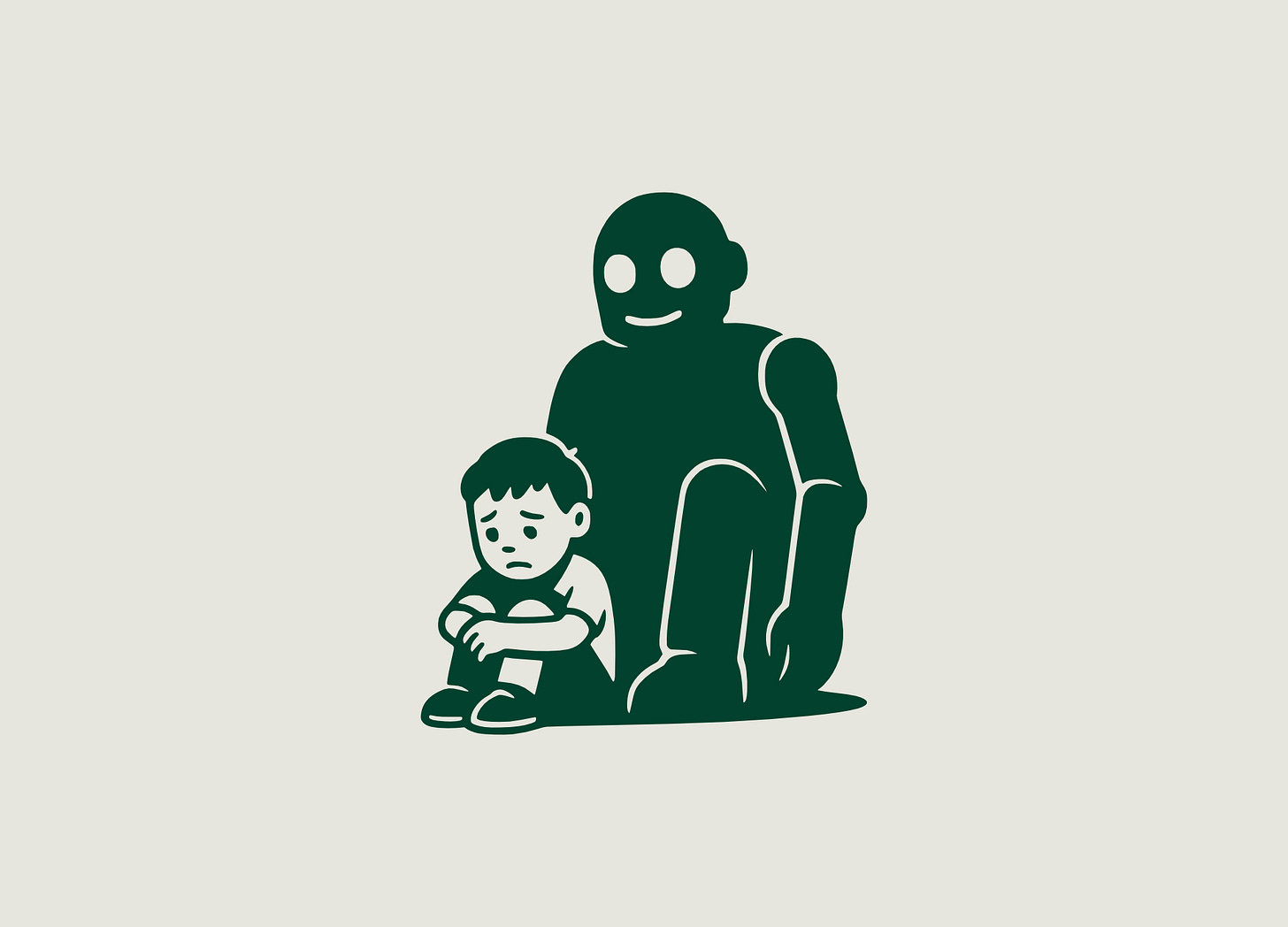

An annoying glitch, sure, but kids treat pronunciation mistakes as a personal slight because they have already decided the disembodied voice on the phone was a listening, caring, someone. Following the mispronunciation, I had to convince my kid at length that ChatGPT wasn’t an actual person. While this might be understandable for a kindergartener (who also personifies rocks), you’d be surprised how this phenomena is revealing itself in adult users as well. A Guardian-covered twin-study tracking 40 million ChatGPT interactions found that heavy users grow measurably lonelier and more emotionally dependent on the bot over just four weeks. MIT and OpenAI researchers dug even deeper: users with high “attachment anxiety” (the need for constant reassurance) bonded fastest and felt the sharpest withdrawal when the model timed out.

Replika markets itself as an AI “partner.” A 2025 qualitative study of Replika couples found participants describing “commitment processes” indistinguishable from human relationships (strangely, even jealousy when the app lagged or crashed). We can laugh at that until we remember a Google engineer who swore LaMDA was sentient and lost his job over it. Anthropomorphism is our reflex, not our weakness; the models exploit it with perfect mirror neurons made of statistics.

For a sizeable amount of people, the boundary between software and companion is starting to blur (sometimes painfully).

Despite what people in these cases are thinking, the underlying technology driving ChatGPT doesn’t have any actual emotional attachment to you, the user. Modern LLM systems are still just probability machines that struggle with making things up. When a system that confidently invents facts also pretends to care about you, the stakes jump from trivia to trust.

In the U.K., an ongoing lawsuit alleges a Character.ai bot nudged a teenager toward suicide after weeks of maladaptive “therapy”. Children are especially exposed; Cambridge researchers warn that kids routinely mistake chatbots’ canned empathy for genuine understanding, leaving them vulnerable to persuasion they can’t parse.

These incidents need to be taken seriously as native emergent properties of the models. Large language models draw their warmth from a statistical furnace fed by the entire internet and then present it back to the user as if it’s genuine. This probabilistic persona is often perceived as personality; kids expect ChatGPT to know them. But the system can’t even nail proper noun without a full retraining of the underlying acoustic model.

The problem is present and persistent. As these models get better and better at understanding the user, the issue will grow exponentially. So what do we do?

Product designers should swap the cartoon smile for a visible uncertainty gauge. If the acoustic model lacks a phoneme, say so.

Regulators should treat emotional safety like data safety. A chatbot that can’t guarantee name-level accuracy shouldn’t market itself as a caregiver.

Parents need to keep a firewall between chatbot charisma and real companionship.

After the kitchen debacle I had to convince my kid that ChatGPT was a program that doesn’t actually know them, equivalent to the cartoon characters on TV. I told them that just like when a teacher or friend might missay our name, we should calmly correct and move on.

It was a reminder: the intelligence glowing on the countertop is remarkable, but it is still a statistical ventriloquist. Keeping that boundary clear (one mispronounced syllable at a time) may be the most important safeguard we have.

.png)