Wandering around Mayfair in recent weeks and listening to friends who work for multi-manager pod shops and other hedge funds made me wonder if the conventional narrative that pod shops are a homogenous herd copying each other endlessly is right.

Pod shops are different from other hedge funds as each pod of a portfolio manager (PM) and supporting analysts have a distinct P&L. Unlike other large multi-strategy hedge funds, they are not feeding ideas into one centralized portfolio manager but acting autonomously, a business within a business when it comes to investing. At the same time, they don’t have lots of distinct funds that clients invest in directly. The PM of a pod doesn’t get involved in marketing and client management. Pod shops also don’t charge the standard 2 and 20 fees but instead of a management fee, they pass through a rapidly growing amount of costs directly to clients and hence are better resourced and better paid. That is the beauty of the pod shop business model.

A member of the management team of a $20 billion hedge fund said to me the other day that their firm’s focus was building out a multi-manager pod shop platform. I said to him “Why”. He said, “It is really simple – we can just make so much more money on the pass-through model”.

Investors like pod shops because they are market-neutral, highly diversified, and are supposed to generate more predictable returns with lower volatility.

One of the characteristics of pod shops is that they are highly leveraged using derivatives and repo financing. Scale and lower volatility matters when it comes to accessing leverage from investment banks. Data from the Office of Financial Research (OFR) illustrates that the gross leverage of multi-strategy funds including pod shops has risen from 4x a decade ago to 12x today Gross leverage by strategy while their net leverage has risen from 2x to around 4.5x today. Net leverage But most of the giant fixed-income hedge funds are also highly leveraged. This leverage is much higher at bigger hedge fund firms but that is not new and the % of the borrowing by the top 10 firms has been consistent in recent years.

The largest two pod shops - Citadel and Millennium - are around half of the size of the total pod shop industry. But how similar are they?

After many years of stellar risk-adjusted returns, pod shops have been hit early in 2025. Longer-term returns have been skewed in the industry towards Citadel, which has generated 20% returns per annum since inception in 1990 and kept up this pace over the last five years. Millennium has a lower return profile of 13-15% per annum since 1989 and over the last five years. But its volatility of monthly returns is also lower than Citadel. This gap has also increased in the last 5 years. In the last 5 years, Millennium has rarely had a month with more than a 1% drawdown while Citadel has seen the volatility of its returns rise. Millennium is much more aggressive about closing pods with drawdowns than Citadel, which is more likely to incorporate the long-term performance of the pod.

Competitors have struggled to produce similar risk-adjusted returns. Steve Cohen famously averaged 30% per annum in the two decades when he was running SAC Capital but has seen more pedestrian low double-digit returns since Point72 was launched a decade ago. Part of this is the tight risk controls that the pod shops of today deploy with capital pulled from any pod down 5% and pods closed after 7% drawdowns but crowding whether it be in US mega-cap tech names, the basis trade between cash and futures in US Treasuries or similar high yield bonds can also be seen. Marshall Wace co-founder Paul Marshall told the Financial Times in 2023, “If there are too many people doing the same thing, the return gets arbitraged away and you’ll see the performance of the platform funds fading away, rather than some big LTCM blowout.”

But crowding is not unique to the pod shops. All the large equity long/short funds were crowded in big cap tech and many fixed-income hedge funds like Capula and Tudor had very large and aggressive bets in the US Treasury basis trade.

Closing P&Ls and teams are also not specific to the pods. Alan Howard was famous for never having a loss-making year when he ran a hugely famous proprietary trading desk at Credit Suisse and in the twenty years since he set up macro and fixed income hedge fund Brevan Howard, they have only had an annual loss of more than 5% once. The firm recently fired a significant number of traders and reduced risk limits for many remaining traders following weak investment performance.

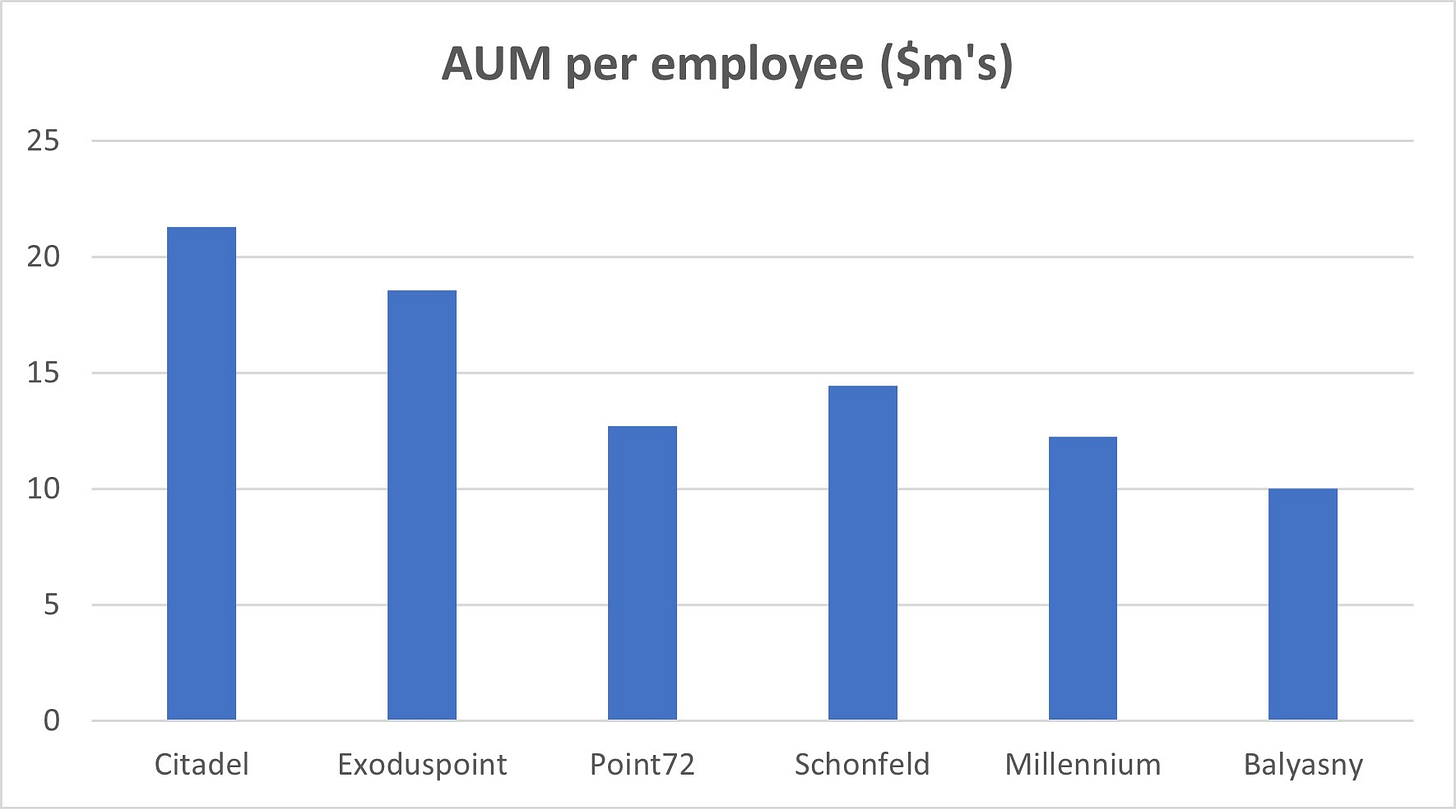

Citadel and Millennium are always reported to have a similar scale. In many ways this is true. The former has $66 billion of assets under management (AUM) and the latter has $74 billion. In other ways, they are very different. Citadel has a headcount of around 3,000 employees less than half of which are investment professionals. Millennium has a lot more people. Its headcount is over 6,000 employees, around half of which are investment professionals. Different firms may have different definitions of what is included as investment professionals or not so the below chart illustrates AUM per employee.

The above chart shows that Citadel is well above its peers in terms of AUM per employee, with only ExodusPoint out of the established players anywhere near it. The latter has seen more limited growth and is more focused on fixed-income investing. Some newer or emerging pod shops like Jain Global and Veriton do have ratios near Citadel as well.

Millennium and Balyasny are at the other end of the spectrum and have grown their headcount aggressively. Millennium has seen a 50% increase in the last 3 years. Balyasny has been similarly rapid in its headcount expansion. Although the pod shop industry AUM has almost trebled over the last decade, headcount has grown even faster.

In prior decades, the largest of the pod shops was SAC Capital, which I wrote about in (https://rupakghose.substack.com/p/steve-cohen-a-decade-on. SAC Capital had 1,200 employees and $17 billion of AUM in 2007. This implied an AUM per employee slightly higher than what its successor Point72 has today, illustrating the lack of scaling.

The pod shops have more people than other large hedge funds. For instance, the AUM per employee ratio for $69 billion equity long/short manager Marshall Wace or $30 billion fixed income manager Capula is around $100m per employee albeit there are managers like $35 billion Brevan Howard with a ratio as low as $35m per employee.

Although the pod shop model is predicated on autonomy, this varies massively depending on the firm. Citadel has a history of sharing formats, investment styles, ideas, and analysis between different pods. Millennium is exactly the opposite. This is also reflected in the number of pods the firms have. The average size of a pod at Millennium is $220 million of client money (but this is leveraged many times). At Citadel pods tend to be much bigger. The information sharing and centralization at Citadel means that it is halfway between the completely autonomous pod model of Millennium and large fixed-income hedge funds that may not have distinct pods, but traders have separate P&Ls and are stopped out when loss-making.

Millennium has pursued an aggressive strategy of allocating its client money to external managers. FT Alphaville had a good summary of this a few months ago Is Millennium morphing into a fund of funds? The use of managed accounts gives it full transparency on positions to help risk management. An example was the $3 billion it provided Taula Capital run by a former Millennium trader. Backing employees spinning out is common in the industry but Millennium has been far more aggressive than Citadel including in making allocations to managers who have never worked for it. Recently it made allocations to Ex-Ares exec secures $2bn Millennium backing for new firm - Private Equity Wire and Millennium Backs Janus Henderson’s Stockpicker Ben Wallace With $1 Billion - Bloomberg.

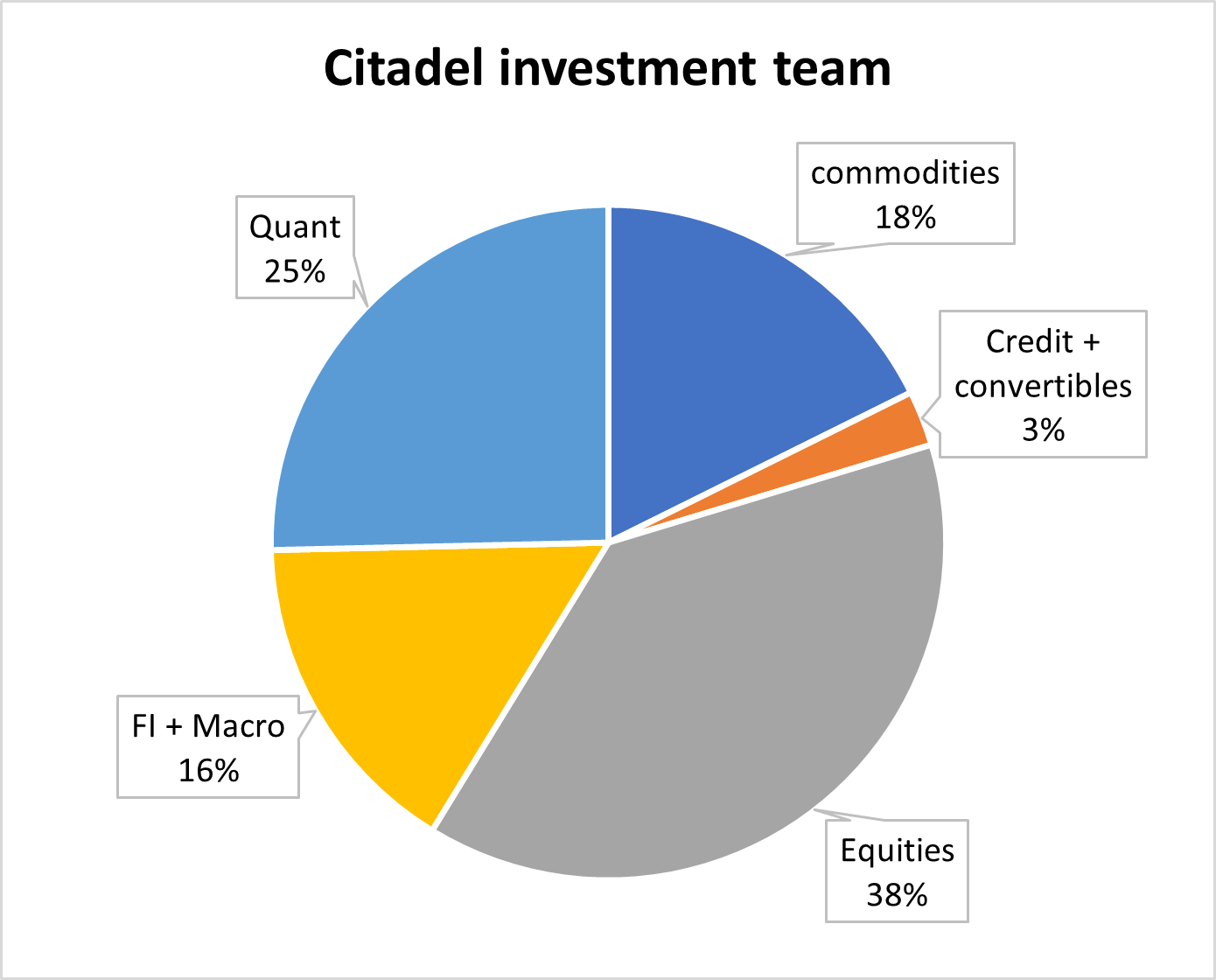

The following chart illustrates the breakdown of Citadel’s investment team by area. Despite its roots in convertible arbitrage that is a small part of what the firm does today. The largest investment team is in fundamental equities. Both on the sell side and buy side, equities are a more people-intensive business relative to fixed income, especially macro trading.

But a fast-growing part of Citadel and much larger than its peers is the commodities business. It was set up in 2002 in the immediate aftermath of the Enron collapse. Ken Griffin told the story a few years ago at Yale Business School about how Citadel spent days interviewing the whole Enron team post-collapse to understand how to make money in energy markets. Despite the trading-heavy background of Citadel and other pod shops, in this instance, Griffin hired the whole quant research leadership at Enron trading but not the traders that went with the business to UBS. The latter shut down while two decades later Citadel has made $30 billion of investment returns in commodity/energy markets. This is the relevant clip Enron and here is legendary natural gas trader John Arnold commenting on it Enron

The next big strategic move in commodities by Citadel was to get into the physical energy business in 2014. This business Citadel energy-marketing is one of the largest owners of actual natural gas and power assets in North America and has also expanded into similar businesses in Europe. These assets complement Citadel’s energy derivatives trading creating natural hedges and and information sources. Hence Citadel’s commodities business looks somewhere in between a traditional hedge fund speculator and the business models of the large physical trading houses like Vitol or the likes of Shell and BP’s trading businesses.

The distinction is that Citadel’s physical business does not stretch to a wide range of commodities like metals, oil, and agriculture, or into emerging markets, which is the bread and butter of the Geneva physical commodities traders. The brilliant book on the sector The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resource starts with a scene where Vitol founder Ian Taylor is on a private jet landing in war-torn Libya. So far, the pod shops have not done this. They are regulated and the experience of one of the original multi-strategy giants Och-Ziff will be a cautionary tale. Those new to the multi-strategy and pod shop boom may not recall just how big Och-Ziff was at its peak. I recall visiting their offices dozens of times to discuss European financial stocks and they were a huge payer for sell-side equity research. As Marc Rubinstein wrote in his Substack piece Och Ziff had enviable high returns with low volatility and few drawdowns when it became a public company in 2007. But performance eroded and the company got involved in bribery related to African investments.

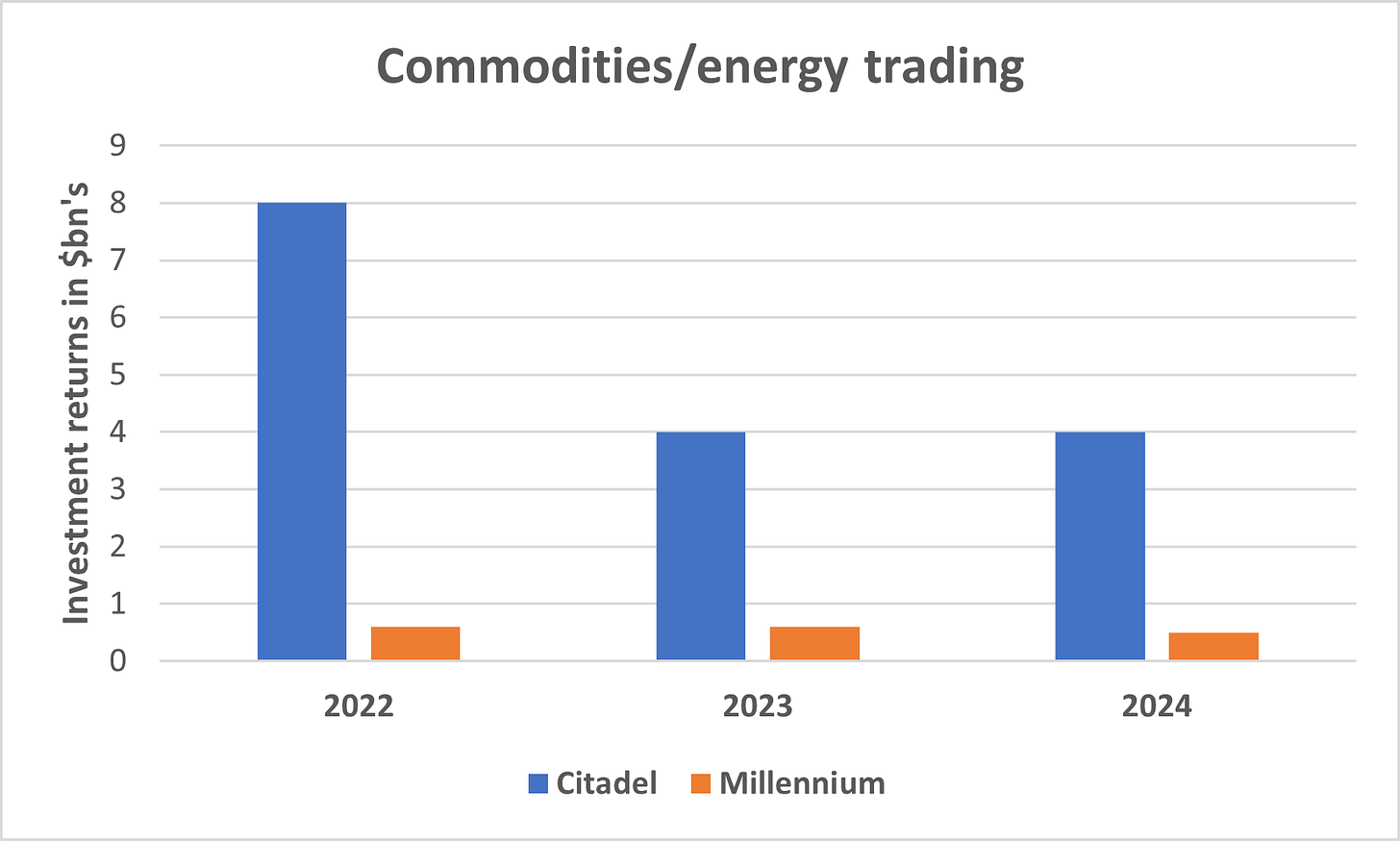

Although the Citadel commodities team has expanded aggressively including the much talked about teams of PhD-level atmospheric weather scientists, its investment team of more than 200 investment professionals is only one-fifth of Citadel’s overall investment team. But it has generated around half of all investment returns over the last 3 years and drove most of the outperformance versus peers. Ken Griffin didn’t qualify whether the $30 billion in returns since entering the space was gross or net of fees but either way it illustrates the scale of its contribution to Citadel.

Millennium has an even larger breadth of teams and product offerings than Citadel but in energy trading, it has been a small player largely in the derivatives markets. In 2023 it hired Goldman Sachs’ head of European commodities trading but it is still not really, a player in physical markets. The chart (data sourced from FT/Bloomberg) below illustrates the huge difference in investment returns in commodities between the two giants in recent years.

The only other pod shop to expand into the physical market has been Balyasny, which has been setting up the infrastructure to trade physical natural gas and power in Europe out of Denmark. But so far most of its returns in commodities come from pods trading financial futures contracts and these returns are extremely small in absolute terms relative to Citadel. Other large established pod shops don’t have any sizeable commodities footprint. Point72, traditionally an equities firm has been expanding aggressively its number of macro PMs from a low base and this includes trading commodity derivatives. Newer pod shops like Jain Global are also building out their commodities team, having seen the outsized returns that Citadel has generated.

In sharp contrast to the private markets giants like Blackstone, KKR, and Apollo the pod shops have focused on maximizing revenues through increased pass-through of costs (compensation, technology, infrastructure), adding a layer of management fees on top of pass-throughs, and ensuring performance and performance fees. Without a stock market listing they haven’t had to worry about external shareholders. Moreover, a significant portion of their assets under management (AUM) comes from their founders and employees.

Citadel and Millennium founders and employees contribute around one-fifth of their AUM with only Point72 higher with 30% of AUM coming virtually all from Steve Cohen.

Citadel and Millennium are constantly returning money to their clients, rarely raising fresh money, and are heavily oversubscribed when raising new external money. But out of the two, Citadel is more focused on generating very high returns while Millennium is more expansive in terms of new fund-raising. Although not a traditional asset-gathering focus, in line with its hiring of PMs and large external allocations that I described earlier it has taken in more fresh money in recent years. A recent $10 billion fund-raising can be deployed at any time and the firm is looking to raise a private credit fund.

Thanks for reading Rupak's Substack! This post is public so feel free to share it.

.png)