I woke as if from a dream with the phrase at the tip of my tongue: “thinking is hard.” What happens when we begin to engage in repetitive patterns of cognitive offloading? Is it possible that certain faculties of mind start to atrophy? When one of the very things that makes us human—thinking thoughts and using language—gets outsourced to another "mind", what remains?

Now many reports are trickling through the web about the creative and at times confronting ways people are using generative AI in their daily lives. Some are using it as a “search engine”—simply asking it routine questions. Others are using it to write holiday card messages, or even (reportedly) their wedding vows. Reports from professors at universities are saying that increasingly students are struggling to read: they’re feeding their long, assigned texts to the chat bot, and relying on summaries instead of spending time with the texts themselves. Or even asking for an extension on an assignment because ChatGPT was down the day it was due.

One might go as far as claiming that college students, in particular, are on the front lines of this cognitive transformation. Universities are increasingly in a state of crisis, because students are “cheating” on their assignments by relying on LLMs to do the work. Online there is an increasingly louder chorus of voices reporting concern that this could lead to wide scale illiteracy. In a recent New York Magazine article, one ethics professor predicts: “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate,” he said. “Both in the literal sense and in the sense of being historically illiterate and having no knowledge of their own culture, much less anyone else’s.” Admittedly, Plato was just as critical of writing. In Phaedrus Socrates critiques writing as such:

For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them.

What might the future hold if we continue on this trajectory of cognitive offloading to AI?

A classic saying goes “every augmentation is an amputation”. At the heart of this insight is the idea that when we gain new capabilities as actors in the world, our plastic minds might change in some fundamental way. Sometimes people (including Sam Altman) liken LLMs to the calculator, that in automating certain ‘burdensome’ cognitive processes, the mind no longer needs to do the same work any longer. Did the calculator make people worse off at math? It did for the students in this study. Yet the LLM is far wider in its scope of what it can do, and so the potential for atrophy is also far more vast. Indeed, students are reporting some of these effects. An article in The Chronicle of Higher Education shared these quotes from students:

“I’ve become lazier. AI makes reading easier, but it slowly causes my brain to lose the ability to think critically or understand every word.”

“I feel like I rely too much on AI, and it has taken creativity away from me.”

On using AI summaries: “Sometimes I don’t even understand what the text is trying to tell me. Sometimes it’s too much text in a short period of time, and sometimes I’m just not interested in the text.”

“Yeah, it’s helpful, but I’m scared that someday we’ll prefer to read only AI summaries rather than our own, and we’ll become very dependent on AI.”

Clearly students are aware of how AI usage in the classroom is affecting them. Yet the article goes on to speculate that part of what is continuing to drive them to use it is anxiety. Students are often overworked, and if they can rely on the AI without harming their grades, they might increasingly find themselves reaching for it. The effects of cognitive offloading can creep in. What might have begun as simply using the AI as a study aid, can quickly spiral as it did for this NYU student:

I literally can’t even go 10 seconds without using Chat when I am doing my assignments. I hate what I have become because I know I am learning NOTHING, but I am too far behind now to get by without using it. I need help, my motivation is gone. I am a senior and I am going to graduate with no retained knowledge from my major.

Perhaps more pernicious than atrophy, simply precluding the user from developing skills that are strengthened through a certain level of cognitive struggle at all. In the New York Magazine article, a student reports using ChatGPT for creating outlines for their essays: “I have difficulty with organization, and this makes it really easy for me to follow.” Yet one can’t help but wonder if her “difficulty with organization” is only exacerbated by using the tool. She’s foregoing the chance to cultivate it, and at worst it may just linger at the same baseline level while they outsource the skill to AI.

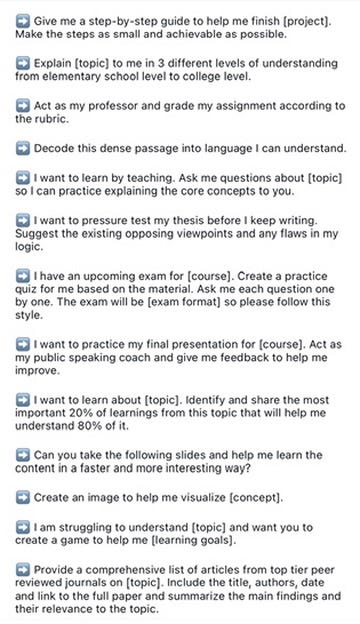

In the most extreme case, one can imagine a user who uses LLM for every cognitive task. From “what should I do?” to “what should I say?” They might go as far as asking it for prompts, even asking the LLM to tell it how to use itself. In fact, OpenAI recently released an Instagram reel where they shared different “genius” prompts from users. One person was doing exactly this: “before asking him [the AI] to do something tell him to ask you 15 questions abt [sic] it so he can better understand you”. Aside from the anthropomorphism, what's interesting is the user is prompting the AI to prompt them back. Essentially offloading the cognitive energy to think about how they should frame the problem (which is perhaps the final frontier in effort of using such an AI).

The prompts above were sourced from an OpenAI instagram post. A classic use case many are finding is using the AI to decode “dense” language into “language I can understand” or “explain it to me like i’m a 10 y/o”. In essence, they're asking the AI to do a kind of intersemiotic translation, translating the language from its natural expression into a different, simpler semantic space. It’s almost like the AI becomes a conduit between thinking and the reader, and this seemingly innocuous act might have some severe consequences: reading, at its best, is supposed to change the reader. By reading a dense passage, one is training one's mind to rise to new forms of expression. It might be a struggle, at first, but that very same struggle grows them or in the very least brings them into new modes of expression. It can be hard. But thinking is hard.

And by using the AI as an interface between difficult texts and the reader, it sheds all nuance embedded in the text. Moreover, who’s to say it’s right? It could very well be that the model hallucinates, changes things spuriously, and glosses over key details that the reader themselves might only have picked up on had they stayed with the text for a while. It might give the student that uses this prompt the feeling of comprehension, without actually having done the work, much in the way they've grown accustomed to looking at cooking reels that give the feeling of having made a dish without having done so. Indeed, preliminary research confirms this: “students who have access to an LLM overestimate how much they have learned.”

This gap between learning and the feeling of learning produced by reading LLM output might lie at the heart of cognitive offloading. It creates a vacuum wherein one has the experience of mastery, but when left to reproduce that mastery without the prosthesis one simply cannot, returning them to using the prosthesis even further and thus only widening the gap. This creates the potential for a feedback loop wherein the dependency on using the LLM increases. In the the limit, we end up with cases like the student that couldn’t go 10 seconds without consulting the AI. Ideally, the LLM is a scaffold for learning, which is stripped away when the construction is complete—leaving a more erudite and informed user. In reality, it might be that the LLM becomes a load bearing member of the user’s cognitive patterns. Strip it away and the whole structure starts to wobble.

This indeed paints a pretty grim picture. Yet not all educators are so despairing. In one New Yorker article “Will the Humanities Survive Artificial Intelligence?”, the author writes about how turning their (Princeton) students on AI, unleashed a flurry of existential and profoundly humanistic insights. It’s well worth a read, and to me it stands out that in inquisitive hands, LLMs indeed can act as powerful scaffolds of the mind. Perhaps what’s most jarring about brushing the New Yorker article against the New York Magazine piece is how in the former, the Princeton students seem eager to learn, and use the LLMs to deepen their humanistic knowledge. They comment on the pure, focused attention of the AI and how rare it is to have that same kind of awareness from a human. In essence, the LLM helps the students in that article engage the material of their rigorous coursework with an almost extended profundity. The author extolls: “Let the machines show us what can be done with analytic manipulation of the manifold. After all, what have we given them to work with? The archive. The total archive. And it turns out that one can do quite a lot with the archive.”

Meanwhile in the latter article, we’re exposed to students who mostly see their coursework as a chore. The article is told more from students’ perspectives anyways, and on the whole they are content to crank out ChatGPT’d essays so they can get back to their other interests (in one case, viewing short form videos until her eyes hurt). Of course there are concerns that AI will only deepen inequality. Here we’re seeing it vividly enacted. In the former essay, AI is helping students deepen their engagement with the humanities and in the latter, it’s portrayed as a means to “cheat” and offload cognition. Perhaps the author of the latter piece is selective. Maybe they simply didn’t find the students that also are using AI to deepen their inquiry with not just the material, but themselves.

It’s possible that this analysis is too severe. That LLMs will be a net benefit towards democratizing education in some vague sense of the word. Yet it seems more that if “thinking is hard” some will simply opt out: offload it to the machine. In an outcome-driven world, where many care more about productivity than how to reach the results, many may simply accede some of that which makes them human: thought.

.png)