Last month, we were discussing what functional literacy means and how many of us qualify. The excerpt below is about the sliding literacy scale defined by the PIAAC, and what it means to score 4 out of 5.

At level 4, adults can read long and dense texts presented on multiple pages in order to complete tasks that involve access, understanding, evaluation and reflection about the text(s) contents … Successful task completion often requires the production of knowledge-based inferences. Texts and tasks at Level 4 may deal with abstract and unfamiliar situations. They often feature both lengthy contents and a large amount of distracting information, which is sometimes as prominent as the information required to complete the task. At this level, adults are able to reason based on intrinsically complex questions that share only indirect matches with the text contents, and/or require taking into consideration several pieces of information dispersed throughout the materials.

To me this pretty precisely captures the task of reading and discussing literature as one might reasonably be expected to do in a college course.

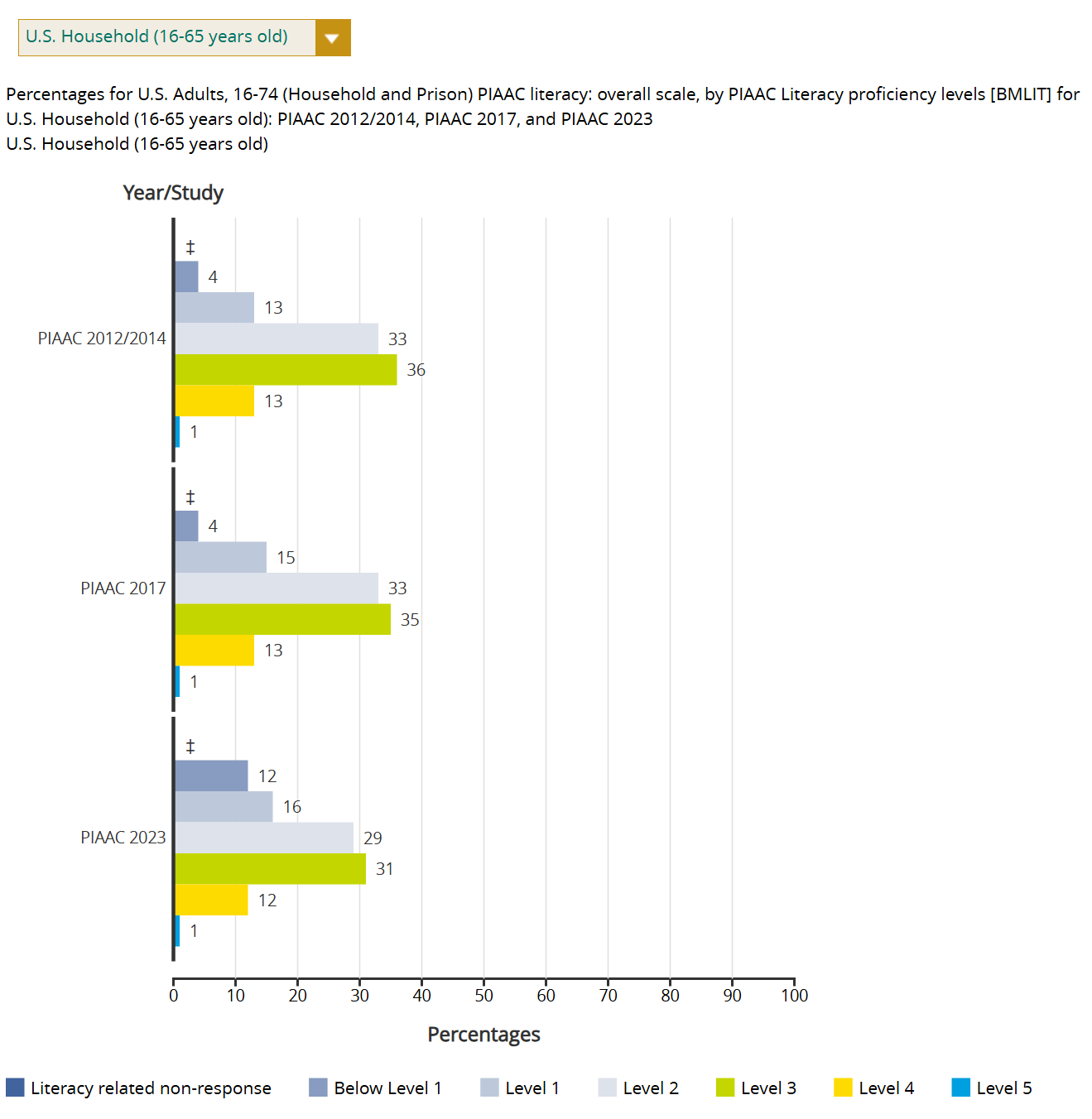

How many US adults score at literacy level 4 or higher? About 12%, or 1 in 8.

So our fed-up professor is objectively correct when he notices that most of his students are “functionally illiterate.” They lack the level of literacy necessary to succeed in a college environment, which is where they are. (Most of them graduate anyway, but that’s a topic for another essay.)

Since over 60% of high school grads go on to enroll in college, we know for a certainty that the vast majority of them are below level 4 in literacy. College kids are functionally illiterate. QED.

But what about those level 5 literate types, the ones who comprise around 1% of adults? What can they do?

This is the subject of a recently released study making waves in the education world. Researchers decided to sit with current college English majors and see how much they understood of what they read. They chose a very challenging text for the modern student, Bleak House by Dickens. Specifically, the first seven paragraphs. Here’s the first one.

LONDON. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas, in a general infection of ill-temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

The methodology is that an interviewer sits with each student one on one and listens to them read the passages from the book aloud. As the students read, they must translate what they read into modern English, explaining what each passage means. They have a dictionary, reference material, and their phones on hand to assist in looking up any unfamiliar terms, such as “Lord Chancellor”.

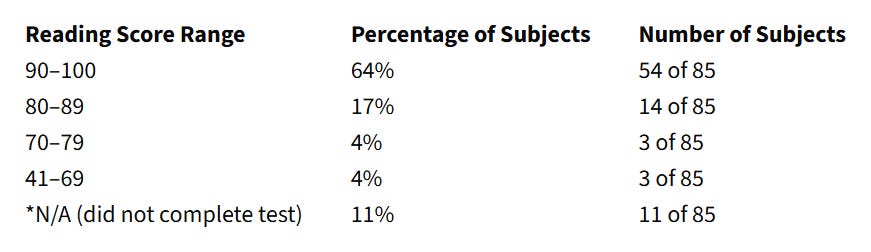

To establish a baseline, they had the students first take a standardized reading comprehension test, the Degrees of Reading Power test, designed for the 10th grade level. Almost all the students scored above 80, indicating they read at or above a 10th grade level.

In other words, these are competent high-school level readers by any national standard.

So how do they do on more complex and archaic language, like Dickens? Not well!

We placed the 85 subjects from both universities into three categories of readers: problematic, competent, and proficient. A summary of our major conclusions gives some basic data for our ensuing discussion:

* 58 percent (49 of 85 subjects) understood so little of the introduction to Bleak House that they would not be able to read the novel on their own. However, these same subjects (defined in the study as problematic readers) also believed they would have no problem reading the rest of the 900-page novel.

* 38 percent (or 32 of the 85 subjects) could understand more vocabulary and figures of speech than the problematic readers. These competent readers, however, could interpret only about half of the literal prose in the passage.

* Only 5 percent (4 of the 85 subjects) had a detailed, literal understanding of the first paragraphs of Bleak House.

To summarize even further for those skimming:

58% of students understood very little of the passages they read

38% could understand about half of the sentences

5% could understand all seven paragraphs

These are college students majoring in English. About half of them are English Education majors, which means they will be teaching books like Bleak House to high school students after graduating. But they themselves cannot understand the literal meaning of the sentences in the opening paragraphs.

What do we mean that they can’t understand the sentences? It’s best illustrated with an example.

Original Text:

As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.

Subject:

[Pause.] [Laughs.] So it’s like, um, [Pause.] the mud was all in the streets, and we were, no . . . [Pause.] so everything’s been like kind of washed around and we might find Megalosaurus bones but he’s says they’re waddling, um, all up the hill.

The subject cannot make the leap to figurative language. She first guesses that the dinosaur is just “bones” and then is stuck stating that the bones are “waddling, um, all up the hill” because she can see that Dickens has the dinosaur moving. Because she cannot logically tie the ideas together, she just leaves her interpretation as is and goes on to the next sentence. Like this subject, most of the problematic readers were not concerned if their literal translations of Bleak House were not coherent, so obvious logical errors never seemed to affect them. In fact, none of the readers in this category ever questioned their own interpretations of figures of speech, no matter how irrational the results. Worse, their inability to understand figurative language was constant, even though most of the subjects had spent at least two years in literature classes that discussed figures of speech.

These problematic readers, which again comprise 58% of the English majors in the study, cannot differentiate between literal and figurative speech in literature. When they encounter unfamiliar vocabulary, they sometimes leap to fantastical conclusions about the meaning of a passage, as this participant who thinks the mention of “whiskers” refers not to a bearded man but to an animal.

Original Text:

On such an afternoon, if ever, the Lord High Chancellor ought to be sitting here—as here he is—with a foggy glory round his head, softly fenced in with crimson cloth and curtains, addressed by a large advocate with great whiskers, a little voice, and an interminable brief, and outwardly directing his contemplation to the lantern in the roof, where he can see nothing but fog.

Subject:

Describing him in a room with an animal I think? Great whiskers?

Facilitator:

[Laughs.]

Subject:

A cat?

Again, these students had full use of dictionaries and even their phones when reading the passages. They were free to look up and search any terms they didn’t recognize. But these resources did not help them understand the text.

Original Text:

LONDON. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall.

Subject:

And I don’t know exactly what “Lord Chancellor” is—some a person of authority, so that’s probably what I would go with. “Sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall,” which would be like a maybe like a hotel or something so [Ten-second pause. The student is clicking on her phone and breathing heavily.] O.K., so “Michaelmas Term is the first academic term of the year,” so, Lincoln’s Inn Hall is probably not a hotel [Laughs].

[Sixteen seconds of breathing, chair creaking. Then she whispers, I’m just gonna skip that.]

For these readers, you can sense the cognitive load of reading these archaic terms and complex sentences. The strain is palpable. And for the 58% problematic subsample, it’s intense enough that all the reference materials and Google searches in the world can’t help. They’re simply overwhelmed.

The “competent” readers too make the same kinds of errors, just not as frequently or severely. Here’s one such reader:

Subject:

O.K. Two characters it’s pointed out this Michaelmas and Lord Chancellor described as sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall.

Facilitator:

O.K.

Subject:

Um, talk about the November weather. Uh, mud in the streets. And, uh, I do probably need to look up “Megolasaurus”— “meet a Megolasaurus, forty feet long or so,” so it’s probably some kind of an animal or something or another that it is talking about encountering in the streets. And “wandering like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.” So, yup, I think we’ve encountered some kind of an animal these, these characters have, have met in the street. yup, I think we’ve encountered some kind of an animal these, these characters have, have met in the street.

In my not so humble opinion, calling this performance “competent” does a disservice to the term. They cannot tell what speech is metaphorical versus literal. They cannot disambiguate between periods of time (Michaelmas Term) and the names of characters, probably because they lack the background knowledge to understand the reference.

I’ve quoted the juiciest bits of student performance already, but you can read them all, including the single example of a proficient reader, in the original paper here.

The authors of the study, who are themselves educators, are suitably shocked and scandalized by the poor performance of these students. You can’t blame demographic shifts or foreign students on these results — the sample is from two public universities in Kansas, almost entirely white. But here’s what the authors say about the level of reading proficiency they hope to assess:

A principal concern for us was to test whether the subjects had reached a level of “proficient-prose literacy,” which is defined by the U. S. Department of Education as the capability of “reading lengthy, complex, abstract prose texts as well as synthesizing information and making complex inferences” (National Center 3). According to ACT, Inc., this level of literacy translates to a 33–36 score on the Reading Comprehension section of the ACT (Reading).

Meanwhile, they point out that their student sample had average ACT scores far below this bar.

The 85 subjects in our test group came to college with an average ACT Reading score of 22.4, which means, according to Educational Testing Service, that they read on a “low-intermediate level,” able to answer only about 60 percent of the questions correctly and usually able only to “infer the main ideas or purpose of straightforward paragraphs in uncomplicated literary narratives,” “locate important details in uncomplicated passages” and “make simple inferences about how details are used in passages” (American College 12). In other words, the majority of this group did not enter college with the proficient-prose reading level necessary to read Bleak House or similar texts in the literary canon. As faculty, we often assume that the students learn to read at this level on their own, after they take classes that teach literary analysis of assigned literary texts. Our study was designed to test this assumption.

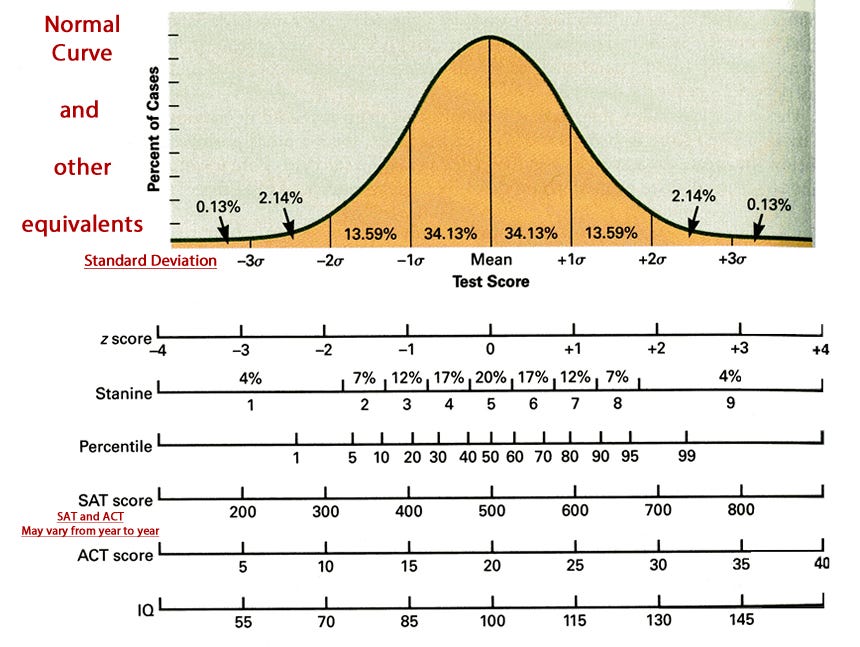

I would like to introduce the authors to a figure with which they may be unfamiliar:

The authors administered a reading comprehension test that by their own estimate less than 3% of the general population of students should be able to pass. 5% did, which is a bit more than you would expect for a mean ACT of 22.4. This is a couple regional public universities in Kansas, not Lake Woebegone. Not every kid who goes there is above average.

I can’t help but read the authors’ own rationale as Straussian — when they write “As faculty, we often assume that the students learn to read at this level on their own”, I can only believe they understand perfectly well this assumption is nonsensical, doomed, a farce. And indeed, to their credit, they don’t pretend that they know how to bring the “problematic” readers up to proficiency. They conclude:

In the end, the lesson is clear: if we teachers in the university ignore our students’ actual reading levels, we run the risk of passing out diplomas to students who have not mastered reading complex texts and who, as a result, might find that their literacy skills prevent them from achieving their professional goals and personal dreams.

To a certain reader this might sound like a demand that college professors step up and instill the necessary literacy skills in their charges. But to me, it sounds more like a lament that standards have fallen to an almost satirical level and there’s no going back. “If we teachers in the university ignore our students’ actual reading levels” — this is clearly the case — “we run the risk of passing out diplomas to students who have not mastered reading complex texts” — this isn’t a “risk”, this is what is currently happening and has been happening for decades, as the authors are surely aware.

I myself took quite a few literature and writing courses in college. This was decades ago, and while I wasn’t an English major myself, most of the students in the advanced courses were. I found that a majority of them had a lot of trouble understanding metaphor and allusion in the assigned reading, couldn’t grasp even obvious themes and character motivations, and could not reliably construct grammatically correct sentences in their own writing.

Almost all of them went on to be awarded BAs in English.

.png)