In conversations about AI and the environment, there’s an important simple intuition I think a lot of people are missing: computing is efficient. Once you have this intuition, conversations about AI and climate become easy to navigate.

Computers have been specially designed to deliver unfathomable amounts of information relative to the energy they use. They are extremely energy efficient for the tasks we give them. I’d go so far as to say they’re the most energy efficient parts of our lives.

Here I’m using the standard definition of efficiency:

\(\text{Efficiency} = \frac{\text{How much valuable stuff we get out of something}}{\text{The energy we put in}}\)

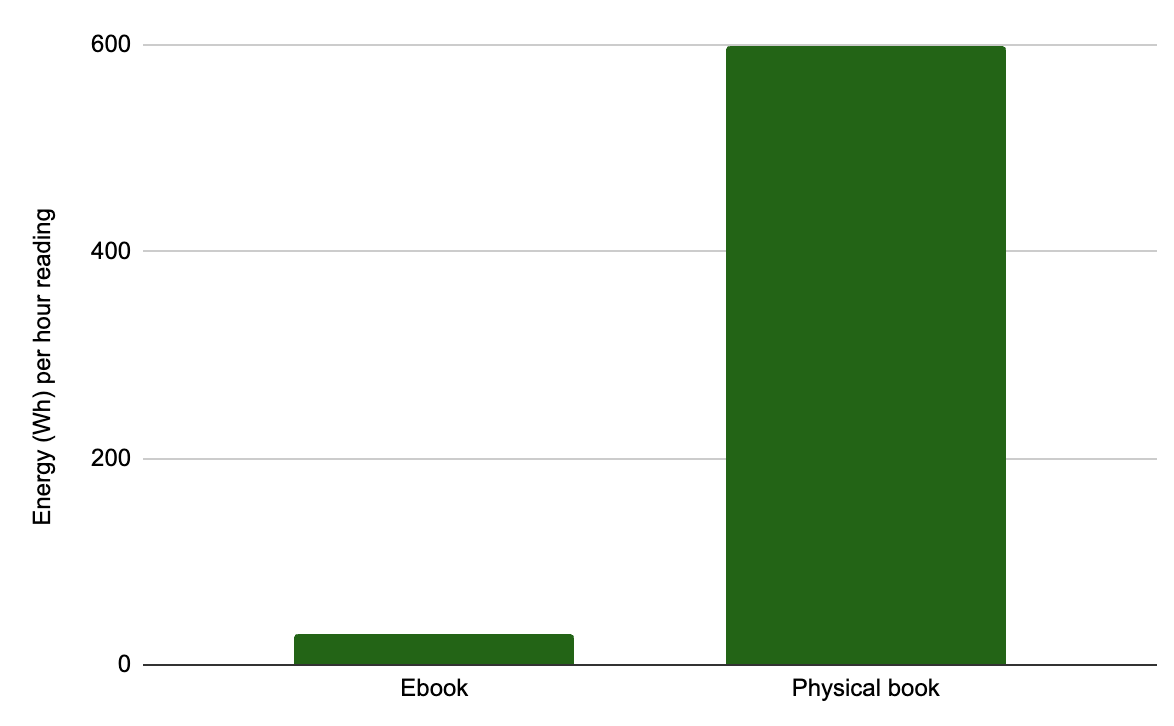

Let’s say I want to read a book. I can either download an ebook or get a physical copy. I read 50 pages per hour. A rough calculation says printing a 300 page book uses about 4000 Wh of energy, so a physical book costs 600 Wh for every hour I read. If I download an ebook to my laptop, the energy cost of the download is negligible, so all the energy I use is just keeping my computer on, which is around 30 Wh for 1 hour of reading.

Why is this difference so big? Physical books deliver information. Since the 1940s our society has been pouring huge amounts of resources and talent into making a rival information delivery system (computing) much more efficient. This is the result.

Computing is basically always going to be drastically more efficient compared to any other way of delivering the same information.

It’s very strange to see people seriously worried about the climate impacts of individual activities they do on computers. There’s a reason climate scientists don’t go around telling people to cut how much they watch YouTube or how often they Google. They know computing is efficient.

I’ve already written about this a lot, but I want to hammer home this specific idea that I think a lot of people are missing. To do that, it’s helpful to step back and see how computing fits into our everyday energy use.

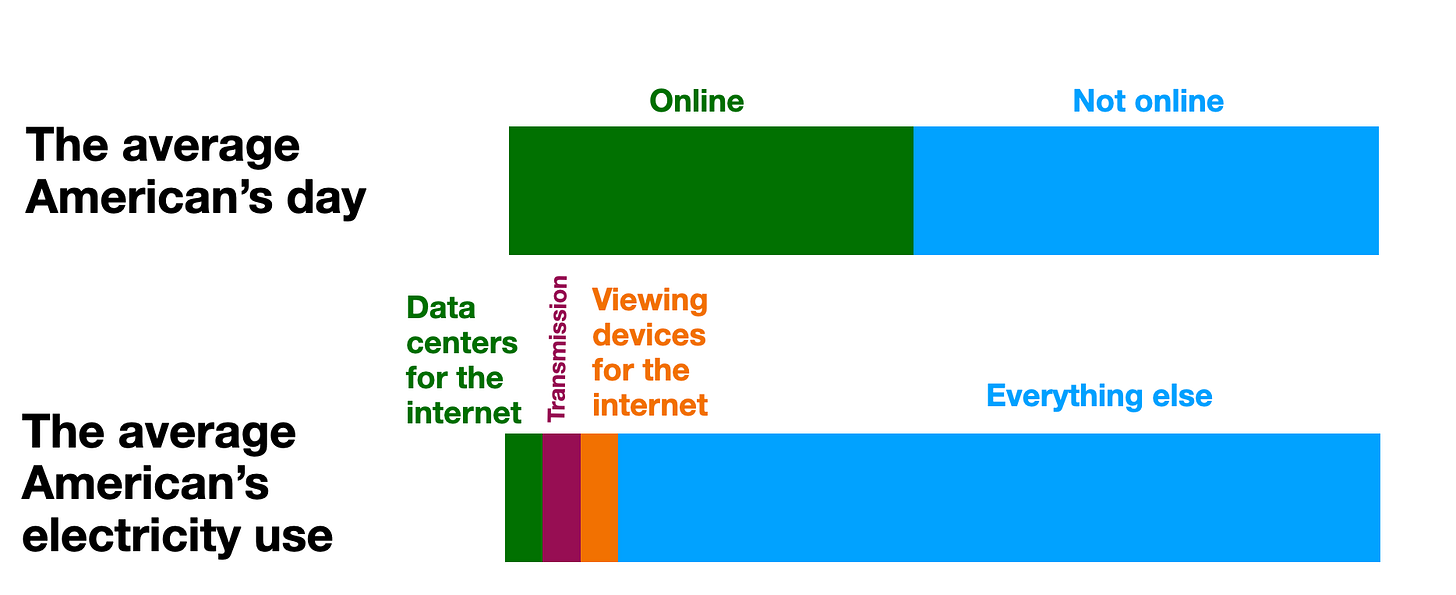

The average American spends 7 and a half hours online, using computers or phones. If we assume the average American gets 7 hours of sleep, their waking life looks like this:

Imagine that there were any other activity that got this much use. Imagine that people spent half their waking life driving, or reading books, or watching movies. What percentage of our energy grid would you expect this activity to take up? What would you consider low?

An obvious answer is that if an activity takes up half our time, we would expect it to use about half of our energy. Without any additional info, we could assume that the internet uses 50% of the energy grid, because everyone’s on it for 50% of their lives.

How much does it actually use?

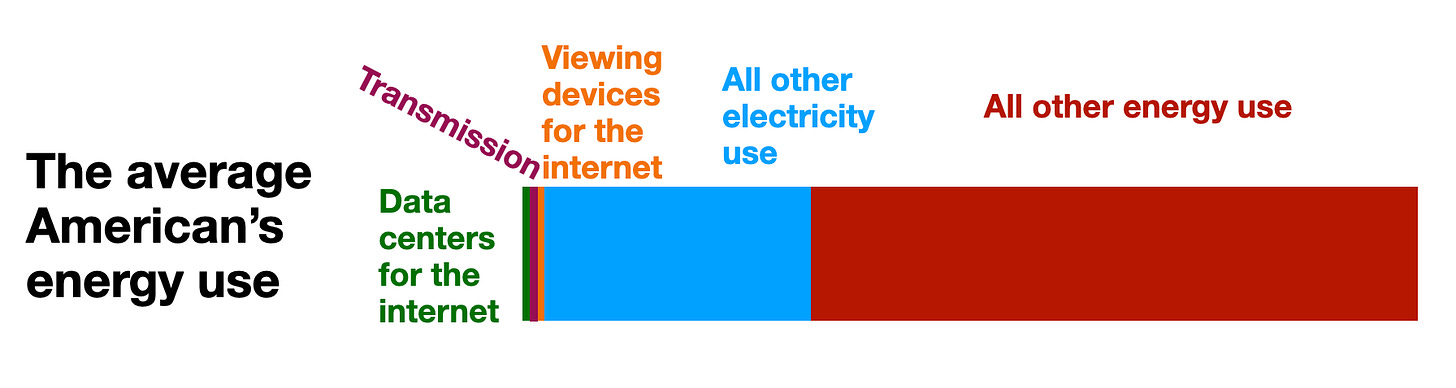

There are three ways the internet uses energy:

Devices to access the internet: phones, computers and TVs.

Transmission: infrastructure to deliver information to and from your device.

Storage and processing of information: basically entirely contained in data centers.

Every single action online, including accessing websites, streaming videos, and using online applications, ultimately involves traversing information through data centers. Data centers store basically all the content of the internet, process it, and control where it gets sent. If the internet can be said to exist in physical places, it’s almost entirely in data centers.

What percentage of our electricity grid would you expect data centers to take up given that Americans spend half their waking lives online? 50%? 25%? The answer turns out to be 4.4%. This includes all data centers in the country, including AI data centers. 33% of the world’s data centers are in the US, so that 4.4% is actually supporting much of the world’s internet use, not just America. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll pretend that American data centers are only being used by Americans.

Individual display devices like phones and computers and TVs use at most another 4% of the electric grid. The energy cost of transmitting data seems to be about the same as data centers. This last one’s a rough guess and I suspect it’s actually lower.

Let’s compare how Americans spend their time to how they use electricity:

This makes it more obvious that the internet is ridiculously energy efficient compared to most other ways we spend our time. It takes up 50% of our time, but is only 12% of how we use electricity.

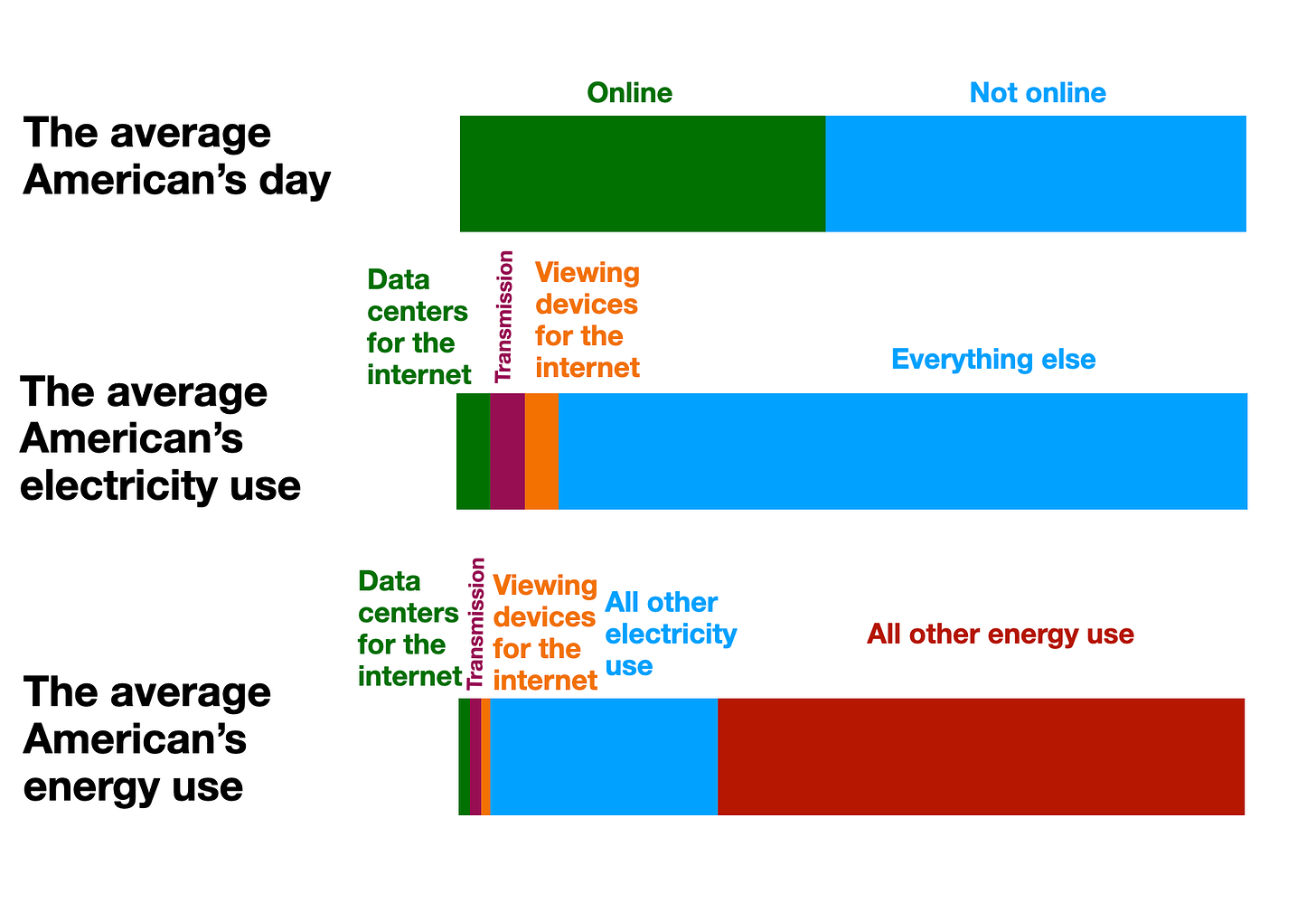

About 66% of America’s energy grid is not electricity, it’s gas-powered vehicles, heating, and industrial processes, so the full per-capita energy breakdown for the average American looks more like this:

When you add all other energy sources, the entire internet shrinks to only 4% of our energy budget. We spend 4% of our energy on something we spend half our lives interacting with. The full infrastructure of the internet is remarkably energy efficient relative to the time we spend using it.

This is why you never hear climate scientists recommend that you cut your internet activity.

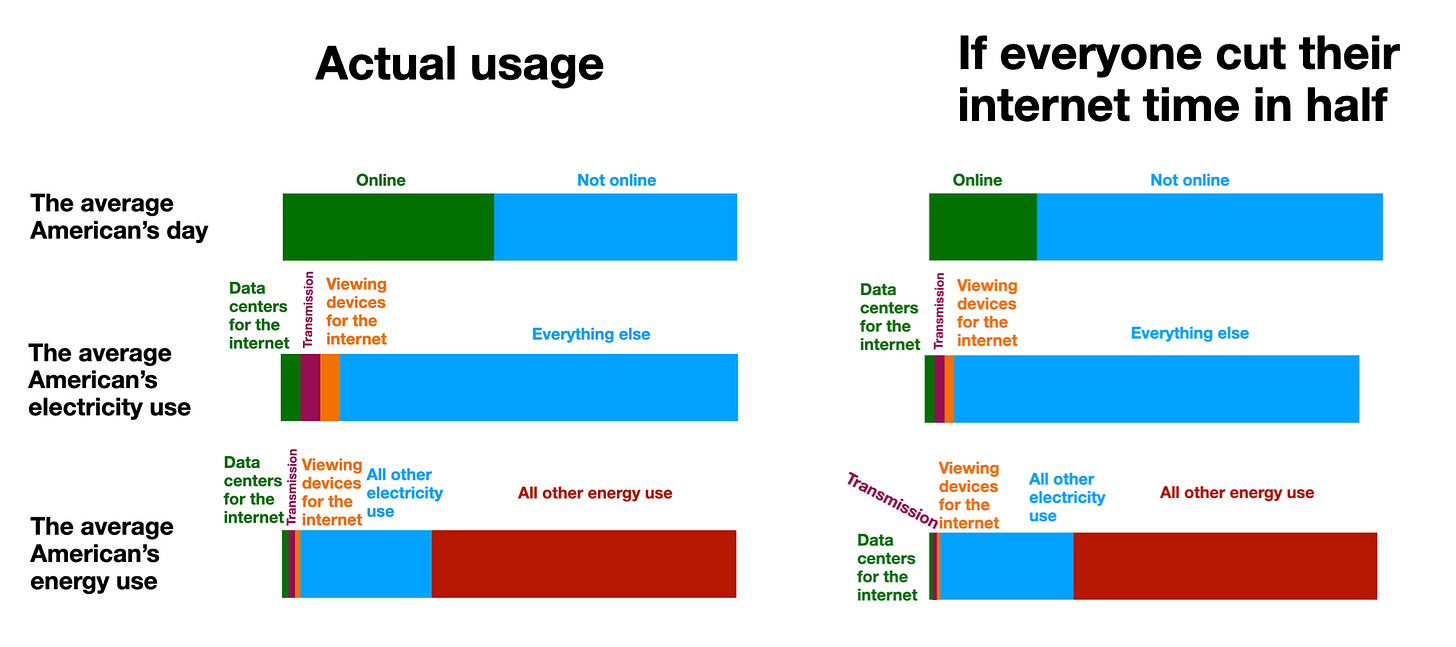

If everyone in America cut their time online in half (and didn’t fill those extra 4 hours with anything that uses any additional energy at all) this is how their energy budgets would change:

This is a huge lifestyle change. It frees up almost 4 hours of your day. Notice that it barely changed the electricity breakdown, and (more importantly) didn’t really make a dent at all in how much energy we use.

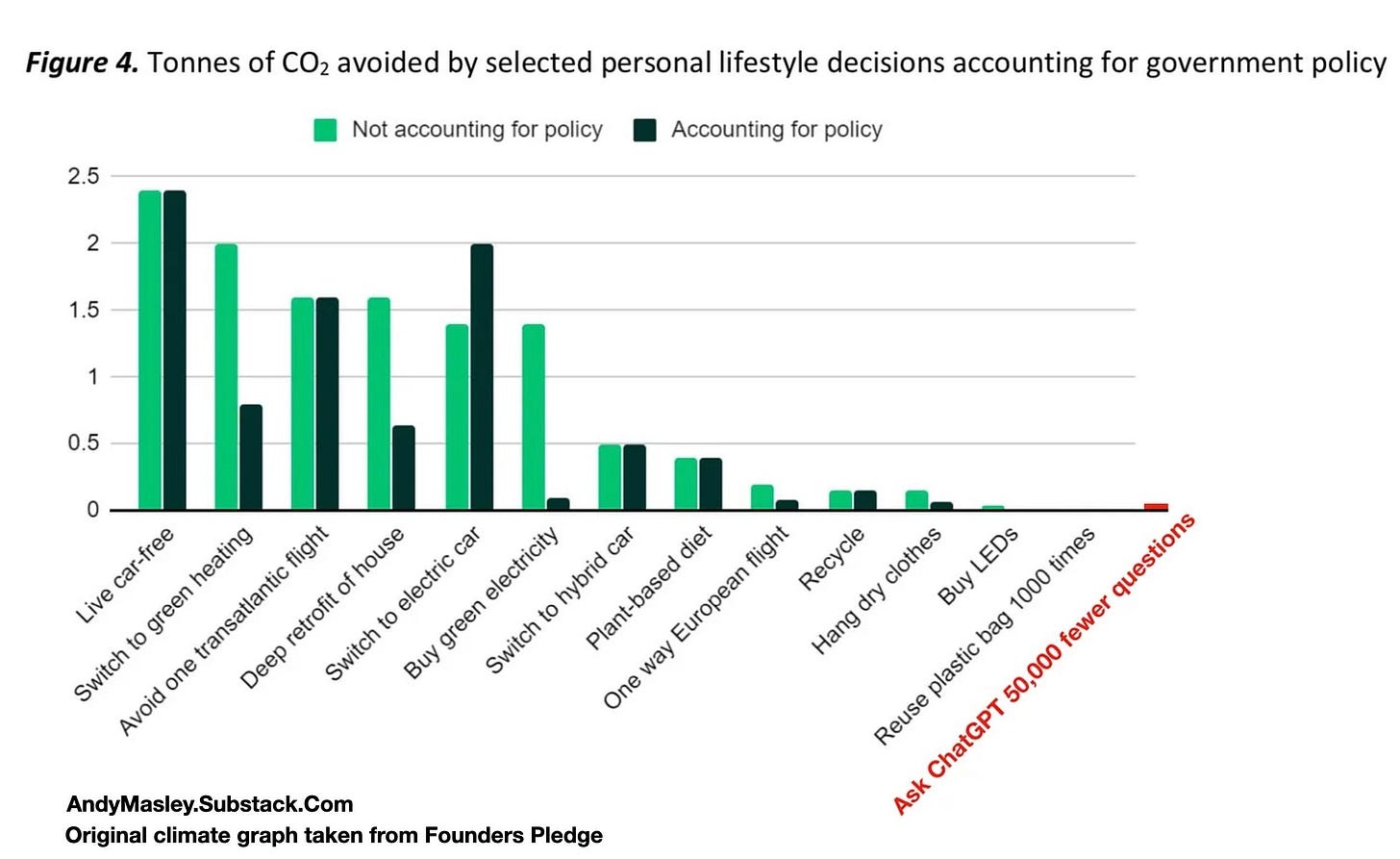

When you consider the average Americans’ energy demands, recommendations for lifestyle changes to help the climate make a lot more sense:

Looking at the first graph, so much of our energy is in the “not electricity” category, like gas-powered transportation and heating. Of course living car-free and switching to green heating and flights will be at the top of a list of how to lower your CO2 emissions. So little of our energy goes into the internet relative to how much time we spend on it. Of course ChatGPT barely shows up. If I added other things we do online to this graph, I’d also have to use crazy numbers to make them visible at all. The simple insight that computing is efficient helps us understand why climate scientists aren’t worried about YouTube or Google or using ChatGPT.

It shouldn’t surprise us that data center energy use is so low, for two reasons:

First, data centers are specifically designed to be the most energy efficient way of storing and transferring information for the internet. If we got rid of data centers and stored the internet’s information on servers in homes and office buildings, we’d need to use a lot more energy. Internet companies want to use as little energy per activity as possible to save money, so they’ve invested huge amounts of money and research on optimizing data center energy use.

Second, computer science is in some ways the art of getting the most useful information out of the least energy possible. Computers have been optimized beyond what the original computer scientists thought was possible. Computer chips manage unfathomable amounts of information using normal amounts of energy. They’ve become basically the single most complicated objects humans produce, with the most complex supply chains. Koomey’s Law predicted that the amount of computations you could do with the same amount of energy would double every 1.5 years. This has somewhat slowed since 2010, but the broader pattern of massive efficiency gains remains stable:

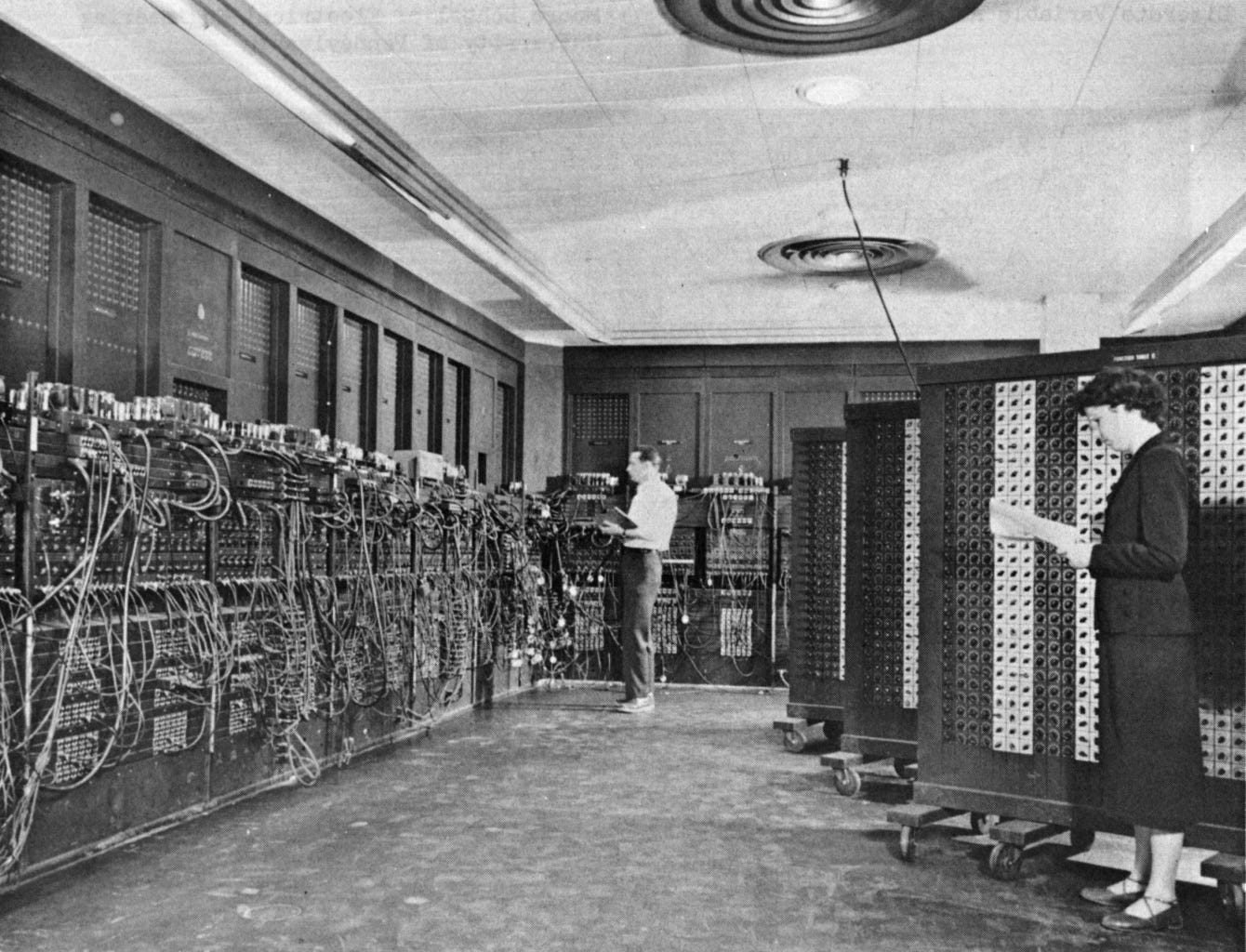

This is a picture of the ENIAC: the first programmable general purpose computer.

A rough back of the envelope calculation implies that running a normal game of Minecraft takes about a trillion computations per second. The ENIAC could perform about 3000 computations per second, and used about 150 kW of power. While the types of computations aren’t really the same, to do roughly the same number of computations your laptop performs when you play Minecraft for one hour, the ENIAC would have needed about 300 GWh of electricity. That’s as much as the entire United States currently uses over half an hour. So when the first computer was invented, running a single game of Minecraft would require half the total electricity in the United States as of 2025. Now it uses such a small amount of energy that it doesn’t make a noticeable dent on your electric bill.

Computers have become very efficient.

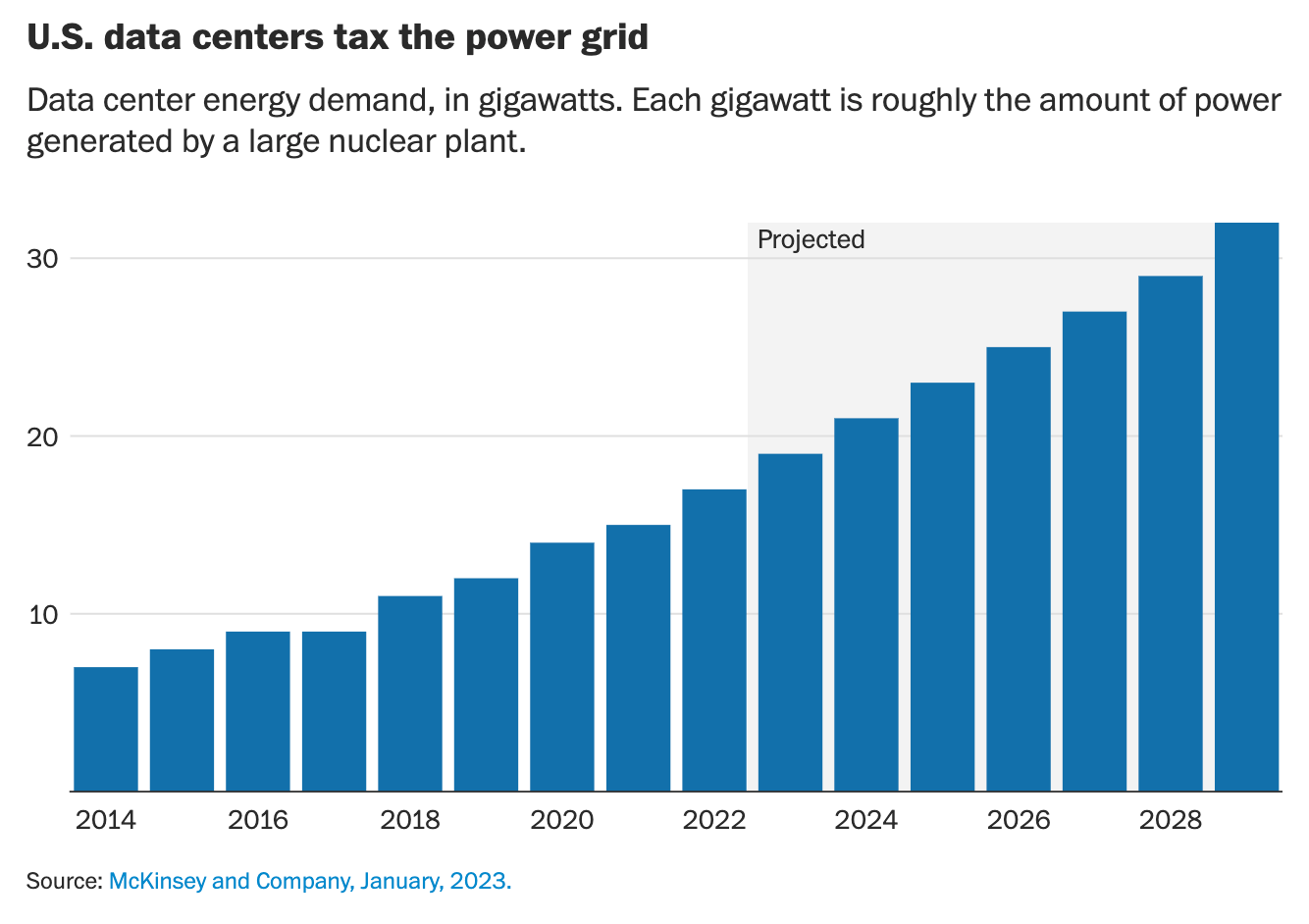

I’ve seen a lot of articles about AI include vaguely ominous language about how data centers already use 4% of America’s electricity grid, and might grow to 6%. Here’s an example from the Washington Post:

The nation’s 2,700 data centers sapped more than 4 percent of the country’s total electricity in 2022, according to the International Energy Agency. Its projections show that by 2026, they will consume 6 percent. Industry forecasts show the centers eating up a larger share of U.S. electricity in the years that follow, as demand from residential and smaller commercial facilities stays relatively flat thanks to steadily increasing efficiencies in appliances and heating and cooling systems.

I think the authors should consider adding “It’s a miracle that this is only projected to climb to 6% given that Americans spend half their waking lives using the services data centers provide. How efficient! Also, 6% of our electricity budget is only 2% of our total energy use.”

Something that disappoints me in conversations about AI and energy is that a lot of people will say things like “It’s so sad that real physical resources like energy and water are being used on AI. That’s all just stuff on a computer. Energy and water should be used on real things like food and shelter.” This shows a lack of understanding of just how important and valuable information is. We should value good information and be willing to spend resources on it. Of course there’s a separate debate about whether AI provides useful information (I think it does), but this point goes way farther to imply that we should only spend physical resources on other physical resources for the sake of the climate.

Information is incredibly valuable. We should value information a lot and be willing to trade physical stuff to get more of it.

Here’s a textbook and big pile of paper. There’s way more paper in the pile than in the textbook:

Which should we spend more energy and water and resources to produce? The only difference between the book and the paper pile is the information in each. Someone who thinks it’s bad to spend physical resources on pure information would have to say we should spend more resources to produce the paper. They would have to say the paper should cost more. This is obviously silly. Information is incredibly valuable, and computers help us get information very efficiently. We should both value information a lot, and be excited that computers get us this valuable information using less energy than any other medium. We can disagree about how useful AI is, but we can’t disagree about whether we should spend physical material on acquiring useful information about the world.

Here’s an interesting pattern. The total amount of physical material per capita in the United States has declined and then stayed mostly flat since 2000:

Meanwhile, the GDP per capita has consistently risen:

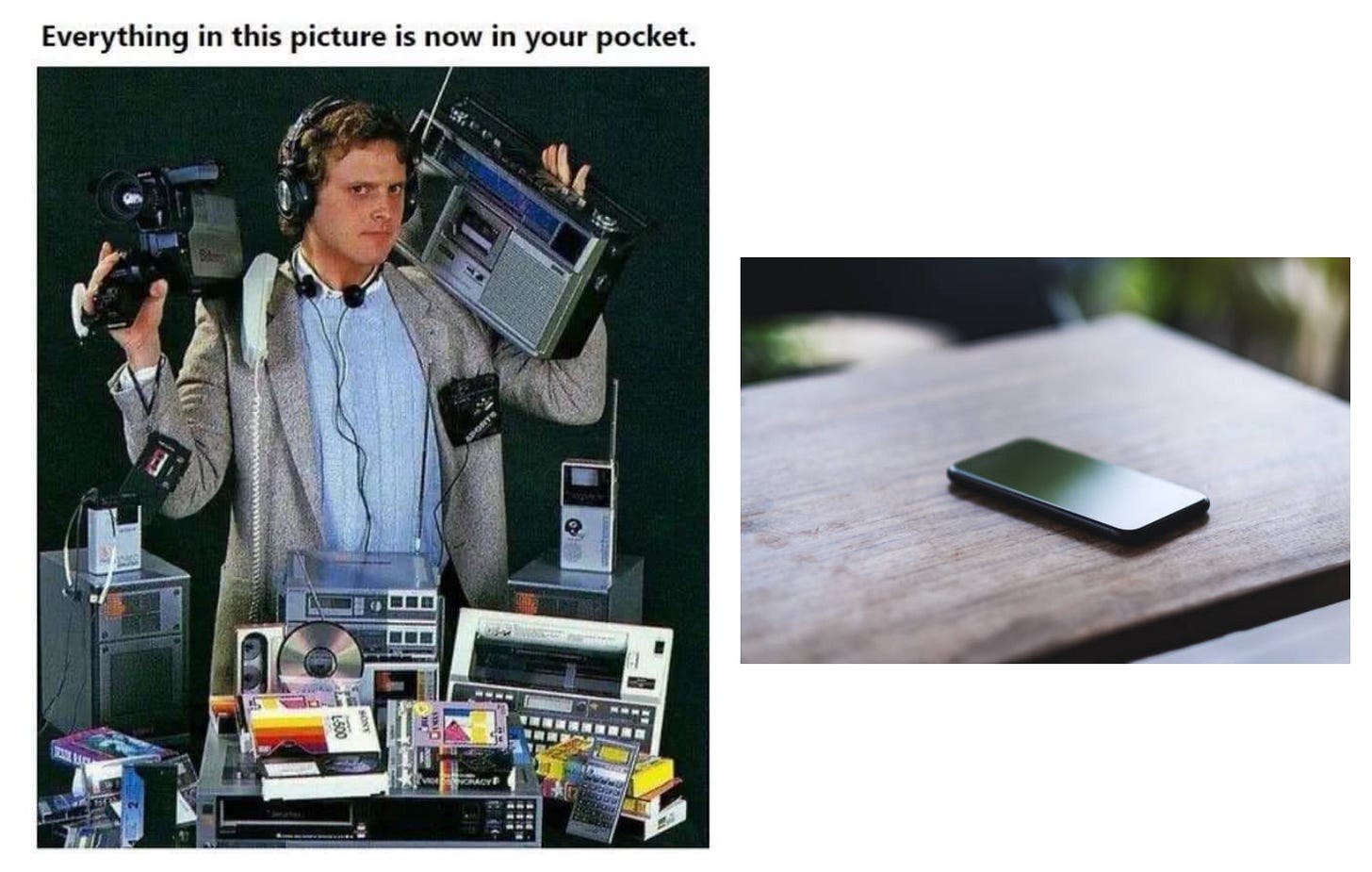

The physical material used per person in the US has declined by 26% since 2000. The wealth per person has increased by 35%. How is this possible? The answer is partly in this image:

Would you rather own all the physical objects this guy has, or a smartphone that can do everything just as well? If you’d trade all of those physical objects for the ease of a smartphone, the smartphone is more truly valuable than all the objects combined. This is how Americans can both be getting wealthier and also have access to less and less physical objects. We don’t need all those physical objects to get the same value anymore!

Economists call this dematerialization: the process of producing more economic value using less physical material.

Because computers (including smartphones) have replaced so many physical objects, they’re helping us live at the same high standards for way less physical material cost. They get us all the same information with less and less physical inputs. This is great news for the climate. It means we can have access to the same nice lifestyle without having to extract nearly as many resources.

I worry that when people look at the energy costs of computing, they’re not considering all the physical processes computers are replacing. We’ve found ways of producing books without paper. People can watch movies without having to drive to a nearby Blockbuster and rent a physical VHS. These are huge wins that are invisible if you only look at the raw energy being used on computers right now. A single data center can look like a lot of energy on its own, but no one was adding up the energy of those hundreds of millions of drives to Blockbuster and back.

When people devalue raw information, what they’re often actually devaluing is dematerialization. Switching from physical to digital systems can help us do way less raw resource extraction, spend less energy on the same activities, and (hopefully) hit our climate targets and keep the world at a safe global average temperature.

Because computers are so efficient, they’re some of the most helpful tools we have to make this happen.

.png)