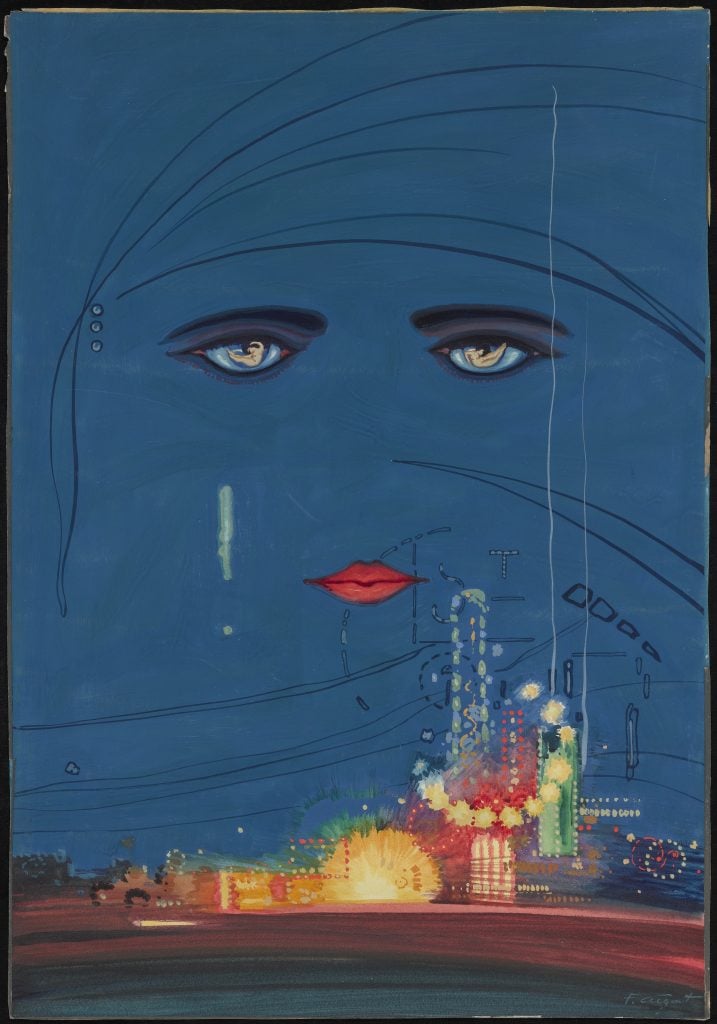

Two sorrowful, enchanting eyes gaze out from the deep blue night sky. A woman’s mouth, with red-painted lips, floats silently below. The glittering lights of a city or an amusement park are visible in the distance. A rivulet of green streams down this phantom flapper’s would-be cheek like a tear.

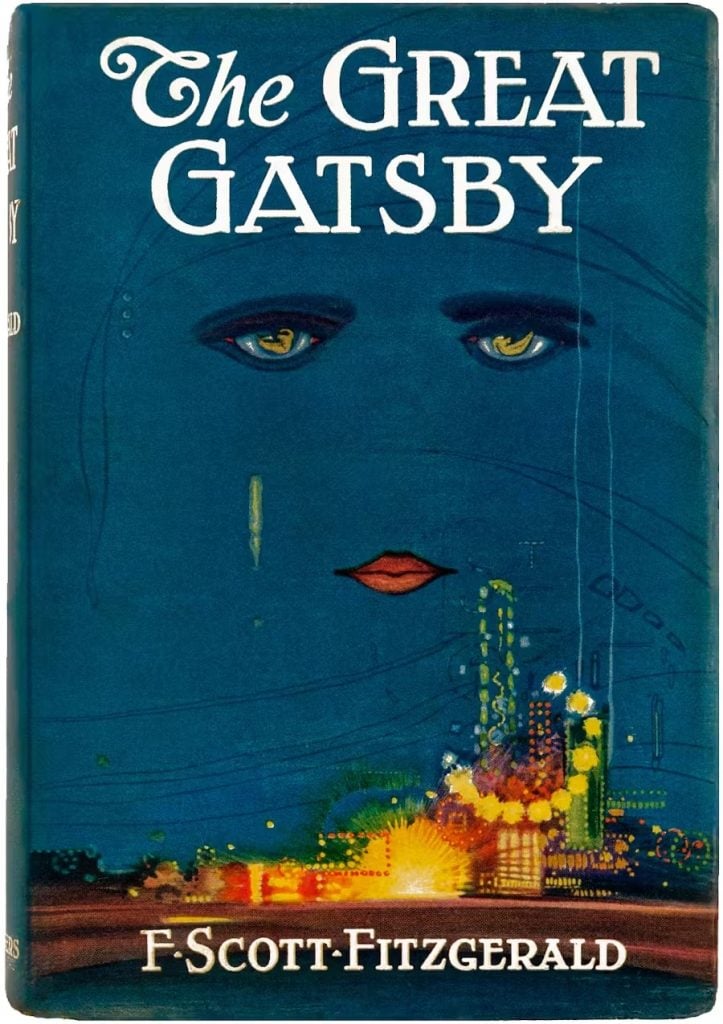

This image, titled Celestial Eyes, is one well-known to readers around the world. A gouache painted by Spanish artist Francis Cugat, it appeared on the cover dust jacket of the first edition of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in 1925. It has remained the standard cover image for the hundred years since. Today, The Great Gatsby is regarded as one of the greatest American novels, and Celestial Eyes, with it, one of the most iconic book covers of all time—and one of the most desirable. In 2024, a first-edition copy of The Great Gatsby with an intact original dust jacket set a new record, garnering $425,000 at Heritage Auctions according to the Artnet Price Database.

Francis Cugat, Celestial Eyes (1924). Public domain.

Frankly, it’s easy to see why. A profoundly abstract image—the face a mere delineation against the night sky—it manages to conjure the greed, lust, beauty, tragedy, and excess of Fitzgerald’s novel. Like Fitzgerald’s elusive protagonists—Jay Gatsby, Daisy Buchanan, Nick Carraway—Celestial Eyes is slippery and contradictory and modern.

What’s more, the book cover image has a far more fascinating backstory than most—it even earned a reference (or two) in Fitzgerald’s final text. To mark the centenary anniversary of the publication of The Great Gatsby, we’ve taken a deep dive into Celestial Eyes and its myriad interpretations.

The Backstory to the Most Iconic Book Cover

Francis Cugat, the artist behind Celestial Eyes, is somewhat of an obscure figure whose career centered on Hollywood cinema rather than the literary elite. Before moving to New York in the early 1920s, the Spanish-born Cugat studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then worked across Europe, Latin America, and Cuba. By 1925, he had set off for Hollywood, becoming a highly sought-after designer of movie posters. But his brief sojourn in New York would prove career-defining when, in 1924, he was commissioned to create the cover for Fitzgerald’s then-unfinished novel, which was woefully behind deadline. Cugat was offered $100 for the job.

Francis Cugat in 1917. Photo in the public domain.

Without a final manuscript to turn to for inspiration, Cugat worked from passages of the incomplete manuscript, then titled Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires. In even his early preliminary sketches, Cugat depicts a giant abstract face floating over a landscape—but these sketches depict a desolate industrial vista rather than the flickering and colorful city lights of the final cover. This original imagery was likely inspired by Fitzgerald’s working title and the book’s vivid descriptions of the “valley of ashes”—an industrial wasteland in Queens, surrounded by a dirty barge-filled river and air filled with the smoke from factories. The location offered a stark contrast to Manhattan and the monied Long Island that it was squeezed between, and it embodied the ugly underbelly of the American Dream. In the end, Cugat depicted the alluring spectacle of the city from a distance, another kind of mythic fallacy.

A first-edition of the The Great Gatsby (1925).

Even at the moment of creation, some saw the lasting value of Cugat’s vision. George Schieffelin, a cousin of the book’s publisher Charles Scribner, pulled Celestial Eyes from a bin of discarded documents at the publishing house. Today, the original art is part of the Graphic Arts Collection at Princeton University Library.

F. Scott Fitzgerald Wrote Celestial Eyes Into His Novel

After seeing early drafts of the dust jacket while in New York, Fitzgerald returned to the South of France to complete his book. Worried that the cover might be used for another, already completed, book, Fitzgerald wrote to his editor Max Perkins, “For Christ’s sake, don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me. I’ve written it into the book.”

circa 1925: American novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940). (Photo by American Stock/Getty Images)

Ernest Hemingway, in his posthumously published A Moveable Feast (1964), confirms that Fitzgerald was inspired by the cover art. As Hemingway recalled: “Scott brought the book over. It had a garish dust jacket and I remember being embarrassed by the violence, bad taste and slippery look of it. It looked like the book jacket for a book of bad science fiction. Scott told me not to be put off by it, that it had to do with a billboard along a highway in Long Island that was important in the story. I took it off to read the book.”

Francis Cugat’s early sketches for ‘The Great Gatsby.’

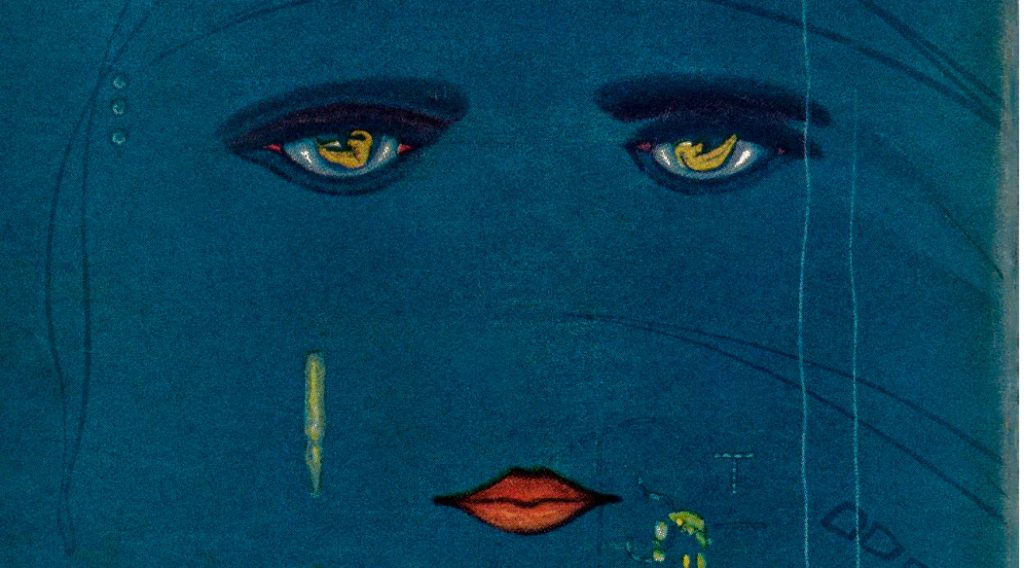

Throughout Gatsby, Fitzgerald writes of a monumental and uncanny billboard for Doctor T. J. Eckleburg, an eye doctor, which looms over the “valley of ashes” and seems to bear witness to the sordid goings-on happening below. Fitzgerald writes, “The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their irises are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose,” continuing, “But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.”

Fitzgerald’s description conjures many defining elements of Cugat’s gouache and was almost certainly inspired by it, but it is not a one-to-one description either. Celestial Eyes depicts a woman’s face, that of a flapper, by the suggestion of a turban marked by thin lines in the work. This opens the possibility, for some readers, that the face on the cover is of Daisy Buchanan, the lost love Jay Gatsby longs for, a rich socialite married to the brutish, “old money” polo player Tom Buchanan. In one passage of the book, Daisy is described as a “girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs.” What’s more, a closer look at the work reveals nude figures hidden in the woman’s tear-filled eyes, hinting at the untoward sexuality that underpins the novel from Gatsby’s longing for Daisy to her husband’s notorious and doomed affair with his mistress, Myrtle.

The Great Gatsby Cover (1925) designed by Francis Cugat.

The Spectacle and the City

In his final version of Celestial Eyes, Cugat depicts a face floating above a cluster of bright lights rendered semi-abstractly. Any real-world inspiration remains ambiguous rather than recognizable, though many have speculated as to the location. New York City, particularly Times Square, is a frequent interpretation, an emblem of decadence of the Roaring Twenties and the Jazz Age. While Times Square is not explicitly described in the book, the Hotel Metropole, a popular gangster hangout in Times Square, does appear.

Others believe the cluster of lights represents an amusement park, likely Coney Island. In this interpretation, the semi-circular shape formed by yellow burst-like marks in the work could suggest a Ferris wheel. Jay Gatsby does suggest that he and the book’s narrator, Nick Carraway, go swimming in Coney Island late one night; at the time, the location was a seaside sight of entertainment, and a popular destination that welcomed the everyman, a contrast to the uncompromising exclusivity and status-seeking of West Egg and East Egg.

A view of illuminated marquees in Times Square at night, New York City, 1920s, Photo by Edwin Levick/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Brights lights are one of the most recurrent motfis throughout the book, a symbol of desire, spectacle, excess, and blindness. Just before the mention of Coney Island, narrator Carraway describes driving up past Gatsby’s house and seeing it deliriously aglow in light one night.

“When I came home to West Egg that night, I was afraid for a moment that my house was on fire. Two o’clock and the whole corner of the peninsula was blazing with light, which fell unreal on the shrubbery and made thin elongating glints upon the roadside wires. Turning a corner, I saw that it was Gatsby’s house, lit from tower to cellar,” Carraway recounts. “At first I thought it was another party, a wild rout that had resolved itself into ‘hide-and-go-seek’ or ‘sardines-in-the-box’ with all the house thrown open to the game. But there wasn’t a sound. Only wind in the trees, which blew the wires and made the lights go off and on again as if the house had winked into the darkness.” He then describes the house as looking like the World’s Fair.

Luna Park lit up at night, Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York City, 1920s. Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images.

Cugat’s dreamlike reverie of lights is a synthesis of all these locations in some ways—the representation of a longing for a moment of ecstatic bliss that may never be reached. “So I don’t know whether or not Gatsby went to Coney Island, or for how many hours he ‘glanced into rooms’ while his house blazed gaudily on,” the passage continues.

Fascinatingly, the long mark of green and yellow pigment that drips down the left of Celestial Eyes has typically been interpreted as a teardrop, separate from the larger cluster of lights. But this mark also doubles as a reminder of the emblematic green light that blinks out against the dark from Daisy and Tom Buchanan’s dock, a warning for approaching boats. Gatsby can see it from his home across the bay, and it comes to represent all that he can never quite grasp. As the closing lines of Fitzgerald’s masterpiece famously read: “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther…. And one fine morning—So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

.png)