Background: Talking with a Ransomware Confessional

In late September 2025, a ransomware operator known as Devman sent me a link to a new Ransomware-as-a-Service platform days before its public launch. For months, the man behind the operation had been working solo on modified DragonForce code. Now he was formalizing the brand and recruiting affiliates.

The timing was odd. Honestly, his whole persona is odd. Just weeks earlier, Devman told me he was leaving the ransomware team to focus on personal matters. Instead of walking away, he built more infrastructure, launched an affiliate program, and positioned himself as a RaaS operator.

He loves to talk. Between July and September 2025, Devman stayed in contact with me through encrypted messaging, starting with an introduction on July 31 that landed as a mix of challenge and flex: “You want to change the life for this???” The attached photo showed luxury watches and exotic cars, the spoils of ransomware operations translated into status symbols.

He knew I was studying him and documenting his activities, but he engaged anyway.

He is loud, tweeting his every step on X and drinking his way through the chaos he created for himself. Reading between the lines, you sense an acceptance that there’s no way out after such crimes. “Life truly is an endless filth with your inner demons,” Devman wrote on August 8. Three days later came what looked like an exit: “I did scram, fuck ransomware.” It didn’t stick.

On August 11, explaining why he didn’t like rap music, Devman described what he saw as the fundamental trap: “They talk about the world they never saw and make lil kids see it as something cool, when in reality crime means that you will never see your kid. You won’t have a happy end. In the end no one has [a happy ending]; some die, some move on to different types of crime as I did, but still stay with a ‘crippled mentally’ and also have a shit load of problems with alcohol and paranoia.”

This wasn’t posturing. This was someone dealing with consequences, smart enough to see the trap but too deep to escape. The paranoia manifested in excessive operational security measures, including multiple passports, which he showed me, forged documents, and constant movement between countries. “Just found out what real paranoia is,” he messaged after a trip to buy another watch. And yet he kept sending me voice messages. Contradictory? Yes. Surprising? No.

And through it all, the work continued. “Wanna negotiate 5 mil ransom?” he messaged on August 15. Not hypothetical, an active extortion. His “exit” from ransomware turned out to mean exiting affiliate work, not ransomware itself.

He wants to be seen, and he keeps inviting onlookers into his world. It’s not the first time I’ve stepped into someone battling underground demons, and it probably won’t be the last. Let’s see what’s in there together.

The Infrastructure Evolution: From Independent Operations to RaaS

On Thursday, September 25th, an unexpected message arrived with an onion link: devmanblggk7ddrtqj3tsocnayow3bwnozab2s4yhv4shpv6ueitjzid[.]onion. It led me to Devman’s new infrastructure, set to go public on Monday. “Take a look. Tell me what you think,” he said. What he invited me to examine was his newly developed RaaS data-leak site.

He was in the middle of transitioning from independent operations to recruiting affiliates. He wasn’t showing me victim listings; he was showing me a business model. I guess it’s the new normal for actors to invite researchers to “review” the illicit activity of the very people hunting them down.

To understand him better and how he ended up here, you need to see the six-month trajectory that brought him to this point.

Mid-April 2025 is when Devman first appeared, working as an affiliate primarily with Qilin (also known as Agenda) and DragonForce operations, with documented ties to APOS. The early victim posts showed competence, but nothing distinguished him from dozens of other capable affiliates moving through the ecosystem. He was deploying ransomware as an affiliate partner for established operations, following established patterns, building a track record.

By July, something changed. Devman broke away from affiliate work and began operating independently, using a modified version of DragonForce’s leaked ransomware code as his own variant. On July 1st, ANY.RUN published a forensic analysis of this new independent operation. The analysis confirmed and documented extensive code overlap with the leaked DragonForce builder, the encryption inherited from Conti, and critically, the implementation flaws. The builder misconfiguration that encrypted the ransom notes themselves. The wallpaper function that failed on Windows 11. These weren’t amateur mistakes; they were the kind of bugs that happen when you’re modifying leaked source code to create your own independent variant while maintaining an aggressive operational tempo.

That same month, Devman launched his first independent infrastructure: “Devman’s Place.”

The terminal-style interface at qljmlmp4psnn3wqskkf3alqquatymo6hntficb4rhq5n76kuogcv7zyd[.]onion showed victim listings with company names and ransom statuses, but notably absent were the countdown timers that have become standard pressure tactics on most ransomware leak sites. The welcome message revealed priorities: “WE ARE ACTIVELY BUYING ACCESS TO COUNTRIES(UK, FRANCE, CANADA), THESE COUNTRIES ARE OUR MAIN PRIORITY.”

That access broker announcement matters. Devman wasn’t just working what he personally compromised; he was buying initial access, cash up front, which signals capital and intent. It’s the difference between an opportunist and someone building a systematic victim pipeline.

Also in July, Devman launched a second leak site, “Devman 2.0,” at wugurgyscp5rxpihef5vl6b6m5ont3b6sezhl7boboso2enib2k3q6qd[.]onion.

The second site showed evolved capabilities. Now, victim listings included countdown timers and explicit ransom demands; the psychological pressure mechanisms were absent from the first site. Several entries noted “(only data exfiled),” indicating operations where only data was stolen without encrypting systems, a pattern that would make more sense once the serious flaws in his ransomware builder became apparent.

On September 25th, the new RaaS platform went live with its first recruitment posts: “WE ONCE AGAIN NEED RESEARCHERS TO DOCUMENT” and “TALANTS WANTED*.”* That same day, the preview link arrived in my messages.

Monday, September 30th, the platform launched publicly. Within hours, monitoring services picked it up, and ransomware monitoring sites began tracking alleged victims listed on the site.

As of October, both earlier leak sites, Devman’s Place and Devman 2.0, are offline. All operational focus has consolidated on the RaaS platform at devmanblggk7ddrtqj3tsocnayow3bwnozab2s4yhv4shpv6ueitjzid[.]onion.

Below is a timeline of significant events:

Figure 3: Timeline of Devman’s operational evolution from affiliate to RaaS platform operator, April-October 2025 – Source: Analyst1

Figure 3: Timeline of Devman’s operational evolution from affiliate to RaaS platform operator, April-October 2025 – Source: Analyst1The Public Face: Victim Listings and Pressure Tactics

The main page of the RaaS platform shows active victim listings, standard leak site functionality with the usual grid of company cards, countdown timers, and ransom amounts.

Figure 4: Devman RaaS leak site showing victim listings – Source: Analyst1

Figure 4: Devman RaaS leak site showing victim listings – Source: Analyst1The ransom demands visible on the public page range from $50,000 to $780,000. But those are the publicly disclosed amounts for lower-tier targets. The higher-value operations referenced in the recruitment materials, the “$150 million extortion” Devman wanted documented, don’t appear on the public-facing leak site. These high-value negotiations are either pending or conducted through private channels, away from the public pressure tactics visible on the leak site.

The FAQ and Rules pages revealed how the operation actually functions, and they made one thing clear: Devman controls everything.

The RaaS Platform: Standard Economics, Selective Recruitment

What I was examining represented careful calculation, not impulse. Sitting in front of the leak site, I tried to understand why he was showing me this before the public launch. We’ve had candid conversations over the months I’ve been documenting his operation, but the access comes with an understanding of roles. I study people like him. He knows that.

The leak site itself answered that question. This wasn’t infrastructure being tested or debugged. Victim listings from the previous Devman 2.0 site were already populated, showing operational continuity. The FAQ was complete. The rules page outlined operational boundaries with the specificity that comes from experience. Everything was ready. What I was looking at wasn’t a beta; it was a controlled launch to a pre-selected audience, with the public announcement scheduled for Monday serving as the official gate opening.

The recruitment model confirms that approach.

Figure 5: RaaS platform recruitment posts as of 29 September 2025 – Source: Analyst1

Figure 5: RaaS platform recruitment posts as of 29 September 2025 – Source: Analyst1The recruitment post dated September 25th, “TALANTS WANTED,” provides a Tox ID for prospective affiliates to initiate contact: 9D97F166730F865F793E2EA07B173C742A6302879DE1B0BBB03817A5A04B572FBD82F984981D. Tox is an encrypted peer-to-peer messaging protocol commonly used by ransomware operators because it requires no central servers, uses end-to-end encryption, and doesn’t require phone numbers or email addresses for registration.

Figure 6: Devman RaaS FAQ page as of 29 September 2025 – Source: Analyst1

Figure 6: Devman RaaS FAQ page as of 29 September 2025 – Source: Analyst1The FAQ announces “V 2.1 IS OUT IN 1 WEEK – MAKE IT ON OUR LIST,” signaling active development. For non-CIS affiliates, the prerequisites are clear and sequential:

- Required deposit: 10k USD minimum

- Required experience working with other RaaS

- Must have own access credentials

Taken together, these criteria function as gatekeeping. The $10,000 deposit required by the Devman ransomware group serves as a significant screening tool for non-CIS affiliates. This high financial barrier poses a significant challenge for security researchers and law enforcement, as it requires them to justify an expenditure that directly funds a criminal enterprise. This makes the deposit a practical operational security measure disguised as a business requirement. In parallel, the experience and “own access credentials” requirements filter for active operators with demonstrated capability. To operationalize that last point, the application adds an explicit proof-of-compromise step: new applicants must “provide data from the company you plan to encrypt, with a data volume of at least 100 GB.” This sequencing creates a clear progression: candidates must first prove their financial commitment, then demonstrate their technical skills, and finally verify they have already compromised a target (financial commitment → demonstrated tradecraft → verified foothold).

The FAQ lists a tiered percentage structure that initially appeared to represent affiliate profit-sharing, a standard feature on most RaaS platforms. However, Devman clarified that these percentages actually define his methodology for calculating ransom demands based on the victim’s annual revenue:

- 22 percent of revenue for companies up to $20 million

- 17 percent of revenue for companies up to $50 million

- 12 percent of revenue for companies up to $75 million

- 7 percent of revenue for companies up to $100 million

- Individual terms negotiated for companies above $100 million

This represents a systematic approach to extortion pricing, scaling demands based on the victim’s financial capacity rather than arbitrary amounts. A company with $80 million in annual revenue would face an initial demand of approximately $5.6 million (7 percent). The pricing structure incentivizes targeting larger organizations, where even single-digit percentages of revenue translate to multi-million-dollar ransoms.

The FAQ does not specify the profit-sharing arrangement between Devman and his affiliates.

Beyond economics, the FAQ also details the tooling provided to affiliates:

- WinLocker. Encrypts local and network drives over SMB, includes a separate GPO-based deployment utility, provides daily updates to the locker stub (claimed 0/21 detection at runtime), and supports an optional mode that suppresses ransom notes on user endpoints, creating the note only on the domain controller.

- Linux/NAS and ESXi lockers. Support partial or full encryption with daily updates.

This note-suppression feature is designed to delay detection in enterprise environments. By displaying ransom notes only on domain controllers rather than workstations, attackers can maintain their stealth longer. This allows the ransomware to spread throughout servers and backups, maximizing damage and lowering the probability that security teams become aware of the attack. A user being unable to access their files should trigger an alarm, but a ransom note would clearly indicate a ransomware attack is underway.

The new RaaS operation also comes with a new attacker panel, used by criminals to conduct attacks:

Figure 7: Attacker Panel login screen

Figure 8: Ransomware Builder screen

Figure 9: Ransomware Panel home screen used to leak victim data

Figure 10: Ransomware Panel attacker statistics screen

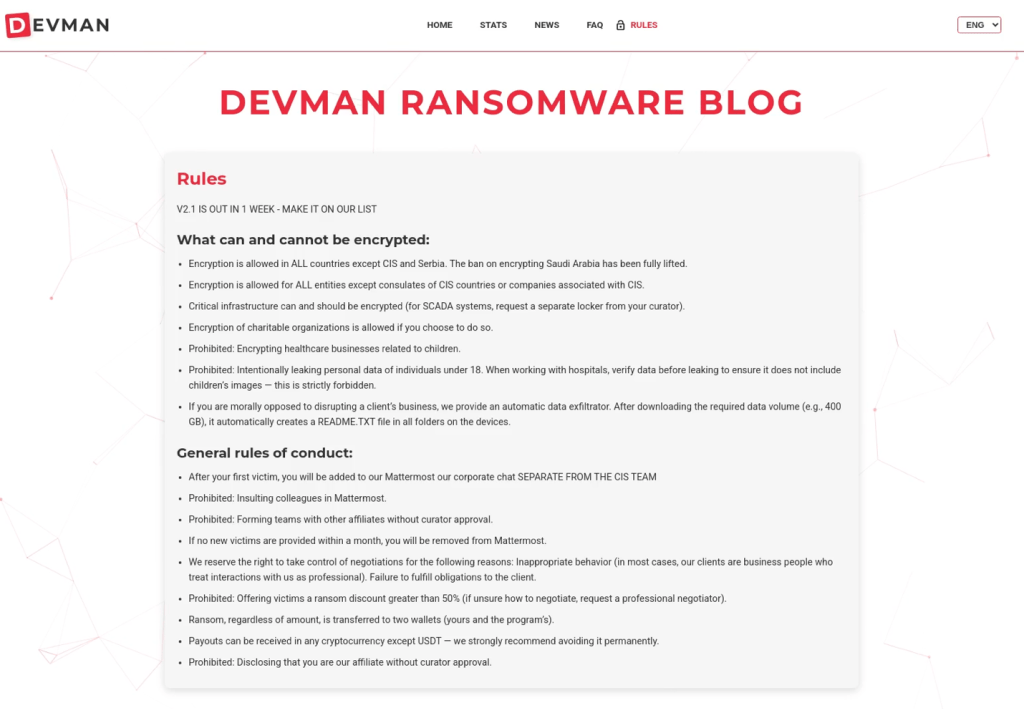

Next, I reviewed the affiliate rules section. This is one of the most useful parts of a leak site, as it tells you exactly what you can and cannot do as an affiliate. Devman wants to ensure total control of his operation and has precise instructions about encryption. This is often brushed over or left at a high level on many leak sites. Although I disagree, I believe it is better to state the rules up front rather than leaving them open to interpretation.

Figure 11: Devman’s RaaS affiliate rules page as of 29 September 2025 – Source: Analyst1

Figure 11: Devman’s RaaS affiliate rules page as of 29 September 2025 – Source: Analyst1Devman’s Rules page lays out the targeting policy in clear operational terms, specifying exactly what’s permitted and what’s off-limits.

- Encryption is allowed in all countries except CIS and Serbia. The ban on Saudi Arabia has been lifted.

- Encryption allowed for all entities except CIS consulates or companies associated with CIS.

- Critical infrastructure can and should be encrypted (for SCADA systems, request separate locker from curator).

- Charitable organizations allowed if you choose.

- Prohibited: Healthcare businesses related to children.

- Prohibited: Leaking personal data of individuals under 18. When working with hospitals, verify data before leaking to ensure it doesn’t include children’s images, which is strictly forbidden.

He explained why he allowed hospital attacks. We didn’t agree. His rationale came from direct experience and direct involvement with Conti leadership. Devman told me he sat in on a hospital ransom negotiation alongside Stern, Conti’s CEO. German Federal Police identified Stern in May 2025, ending years of speculation about one of ransomware’s most sought-after figures. They were listening to administrators on a live call with their insurance company. The hospital hadn’t muted the line. “After that I lost fate in hospitals,” he told me. “I was sitting in an office with stern, listening to the live call of the caller and the hospital. So well they did not turn down the Mike and literally where counting. Comparing the ransom and payouts to dead people. And I was like wtf are we the bad guys here?”

This wasn’t secondhand knowledge or an affiliate rumor. Devman was physically present in a Conti operation center, sitting beside the organization’s CEO during an active hospital extortion. Conti, before its 2022 dissolution, was one of the most prolific and damaging ransomware operations ever documented, running like a legitimate tech company with over 100 employees, structured departments, HR, and even employee-of-the-month bonuses. The fact that Devman had this level of access to Stern during live negotiations places him far beyond typical affiliate status. He was embedded in Conti’s core operations, learning tactics and philosophy directly from leadership that would shape the ransomware ecosystem for years after Conti’s collapse.

When I pressed him on hospital targeting, his response invoked geopolitics: “Man the Americans bombed Belgrade killed civilians most of my affiliates are from cis and Serbia in fact all of them. I did talk about it what I heard was ‘wtf Americans literally bombed our hospitals with uranium.'” To be clear, he did not claim affiliates were killed in 1999; he cited the NATO bombing as justification. The 1999 campaign, depleted uranium munitions, civilian casualties, damaged hospitals, for his affiliate base that wasn’t abstract history. It was lived grievance. American hospitals weren’t neutral ground; they were fair retaliation.

The moral gymnastics were clear. If hospitals treat patients as balance sheet entries, and if Western military operations caused Serbian civilian casualties and infrastructure damage, why should he treat American hospitals differently from any other business? The insurance industry’s calculus, combined with geopolitical grievance, had given him his own calculus. The 1999 NATO bombing was real; civilians died, hospitals were damaged, and depleted uranium munitions were used, though the long-term health effects remain scientifically contested. But legitimate grievances about past conflicts don’t justify harming patients who need treatment now. We stayed on opposite sides of that line.

Two elements stand out on the critical infrastructure side: the explicit permission to impact critical infrastructure, and the instruction to “request a separate locker” for SCADA systems. That instruction implies a SCADA/ICS-specific payload is maintained or planned, signaling planned support rather than ad hoc experimentation and aligning with the platform’s broader critical-infrastructure posture. Separately, Devman told me a SCADA/ICS locker is available to affiliates for approved operations; that claim remains unverified, but if accurate, it elevates both sophistication and threat level for operators targeting industrial environments. Combined with note-suppression and the proof-of-compromise intake requirement, the platform is designed to maximize operational impact before detection.

The children-related restrictions are absolute, and the hospital-data verification requirement reflects awareness of how quickly law-enforcement attention escalates when minors are involved. Taken together, the permitted targeting prioritizes leverage in enterprise and public-utility environments, while the restricted targeting establishes a hard red line around minors. However, RaaS operations often publish similar statements that go unenforced when profits are at stake. Hopefully, Devman enforces this because ransomware attacks are awful, but targeting children is deplorable.

With targeting defined, the platform turns to governance. The General Rules section that follows sets operational expectations for affiliates, covering conduct, team formation, activity cadence, negotiation control, discount limits, payment routing, and disclosure restrictions.

General rules:

- After the first victim, affiliates are added to Mattermost chat SEPARATE FROM THE CIS TEAM

- Prohibited: Insulting colleagues

- Prohibited: Forming teams without curator approval

- No new victims within one month results in removal

- Operator may take control of negotiations for affiliate misconduct or failure to meet obligations

- Victims cannot be offered ransom discounts greater than 50%; if unsure how to negotiate, affiliates should request a professional negotiator

- Ransom must be transferred to two wallets simultaneously

- Payouts are permitted in any cryptocurrency except USDT

- Prohibited: Disclosing affiliate status without curator approval

A few elements of the General Rules stood out. Most RaaS providers do not explicitly state how to talk to victims. Devman demands a level of respect, something I have not seen in many other operations. Again, this only matters if enforced. Offering the use of a professional negotiator also adds another layer of complication for victims. I’m unsure if Devman employs professional negotiators, but if he does, it could complicate negotiations. Many affiliates are technically savvy but lack negotiation skills, giving the upper hand to the victim, who typically hires a negotiator to represent them in extortion talks.

I also found it interesting that Devman wants to control how affiliates work together. Many affiliates operate in small teams. This restriction demonstrates that Devman intends to control the criminals working for him and insists on approving teams himself. Finally, the fact that he has to state that insulting colleagues is prohibited made me laugh. Ransomware operations are almost always consumed with drama. Good luck enforcing that one.

While understanding Devman’s operational structure was important, an incident from earlier this year revealed a different aspect of the ransomware ecosystem: the sometimes-blurred lines between observation and participation in the criminal underground.

The Alleged Extortion

Before I detail what Devman told me next, I need to be clear: I cannot confirm or deny his claims. You should make your own judgment about what is true or false based on the allegation described below.

Earlier this year, Devman made a claim that genuinely shocked me. He alleged that the person behind the “GangExposed” account on X (formerly Twitter), handle @GangExposed, attempted to extort him. If you’re unfamiliar with GangExposed, the account is known for posting information about threat actors, often including photos and videos claiming to identify real-world individuals behind criminal operations.

Researchers who know my position on attribution will understand why I strongly oppose “take-my-word-for-it” attribution. Law enforcement may make attribution claims publicly and withhold evidence during active investigations to avoid jeopardizing a case; as researchers, we don’t have that constraint. Accordingly, I cannot verify the accuracy of GangExposed’s identifications, nor can I independently substantiate Devman’s allegation. Further, normally, I would not post accusations about a researcher, but the truth is long before Devman’s allegations, I have questioned GangExposed motivations and am unsure of what to think of him.

Still, based solely on the account’s public activity, I’ve seen no evidence to indicate the operator is malicious or involved in criminal activity, which is why Devman’s claim surprised me. What follows is presented as his allegation, not as a statement of fact.

In June 2025, Devman, says GangExposed reached out to him and began a dialogue questioning his activities and associations with ransomware groups. The conversations began on X and quickly move to Telegram where the majority of their interactions took place.

Jun 22, 2025 — 12:19 PM

- Devman: “You know GangExposed?”

- Jon: “Just what I see posted publicly. I don’t know much about him, but I wish he would include sourcing and evidence in his posts.”

- Devman: “Yeah bro uses chat gpt”

- Devman: “alot)”

- Devman: “Bro thinks I am trump”

Note: The persona Trump , that Devman references is one of the criminals involved with the Former Conti Ransomware operation

- Devman: “Like how bad you need to misfire”

- Devman: “Gang exposed lmao is so bad”

- Devman: “Some are real doxes but yeah me and trump lol”

- Devman: “Far from reality”

- Jon: “the information they’re posting… It just seems too convenient without a clear explanation or evidence of where it came from. I could be wrong, but my gut just tells me something is not right.”

I then asked Devman if he could provide any proof that this conversation took place. He provided me screenshots that he claims took place between him and GangExposed discussing the dox and extortion:

Figure 12: Alleged conversation between GangExposed and Devman

Figure 12: Alleged conversation between GangExposed and DevmanCombined Transcript (Translated to English)

- [12:13 PM] X: Pay, I’ll share real info. I won’t help you for free anymore.

- [12:15 PM] (quoted/trimmed message, likely from O): “Горжусь прошлой карь…” (truncated in screenshot) “Или не купился” (“Or didn’t you buy it?”)

- [12:15 PM] O: It’s a pity you didn’t buy it.

- [12:16 PM] X: I’m not playing with you now. I made an offer, what happens next is up to you.

- [12:17 PM] O: You don’t buy a pig in a poke. (lit. “They don’t buy a cat in a sack.”)

- [12:17 PM] X: 0.3 is the final offer. Or don’t bother me. (BTC implied)

- [12:18 PM] X: I’ll send everything I have; figure it out yourself after that.

- [12:18 PM] O: Tell me my real name.

- [12:18 PM] X: I’ll send everything I have, only what I have on you. (trimmed line continued)

- [12:19 PM] X: 0.3 final off… (truncated in screenshot)

⸻

- [10:21 PM] O: Here’s what I proposed to you.

- [10:21 PM] (quoted message): If you make it so they pay.

- If I make it so they pay, 10 percent will be too little.

- [10:21 PM] X: If I make it so they pay, how much do you want?

- [10:21 PM] O: A negotiator wouldn’t hurt me.

- [10:21–10:23 PM] (quoted + reply, edited):

- X: How much do you want?

- O: I don’t want anything, really. I want you to keep your word. I don’t intend to do business with you, but there’s no point in getting in the way either, transfer the promised 1 BTC and we’ll be on good terms (with you again). (edited 10:23 PM)

- [10:26 PM] O: I’m not acting against you out of malice but on principle. We made an agreement back then, consider it a handshake. I showed you a source of information (even if it wasn’t what you expected, that it would be a rat/informant), so I consider you indebted. 1 BTC. I respect those who keep their word.

- [10:27 PM] X: I always keep my word.

- [10:27 PM] O: Mdaa…

- [10:27 PM] O: Fuck off.

On October 6th, 2025, as I was finalizing this report, I followed up again on the topic asking Devman about GangExposed.

- Jon: I know you said GangExposed tried to Dox you. Can you tell me what ever happened with that interaction with him?

- Devman: I first through he was crazy but then I realized he actually was a genius, he is a real genius he made a great mind game with everyone first pretending crazy but then everything clicked he was playing a great chess match with everyone including me. I don’t know if he has my valid dox but this guy is a god damn genius.

Based on all of this, its unclear to me what exactly took place, but the topic is interesting and shows a side of ransomware we dont see often, a threat actor being threatened by a researcher (allegedly). If you think about, it’s a bit ironic since this is what ransomware criminals do to others. Devman, however, seemed unfazed and maintains that GangExposed had him pegged as the wrong guy and refused to pay the extortion. Not long after this GangExposed was doxed himself and his account has been dormant ever since.

Due to this, I did not obtain GangExposed account of this situation. GangExposed has been dormant on X since the dox that took place earlier this summer. However, if he does provide further context, I will update this report. (@GangExposed).

Update (17 October 2025)

Analyst1 published this report on October 15, 2025. Within hours of publication, GangExposed responded to Devman’s allegations. His response included confirmation of the screenshots’ authenticity, justification of his actions, and criticism of this investigation. Before presenting his response, I should address why I did not reach out to GangExposed prior to publication to obtain his account of these allegations. In hindsight, I should have made a direct attempt. I did not reach out because of two previous unanswered contact attempts on June 11, 2025, and August 11, 2025, for unrelated matters. Based on this pattern, I concluded outreach would be unsuccessful. That may have been an incorrect assumption on my part. His initial response and subsequent posts are shown below.

Figure 13: GangExposed’s response to this report and the extortion allegations.

Figure 14: Additional responses from GangExposed following publication.

Before I address the response, I think the reply made by @UK_Daniel_Card says exactly what I felt as I first read GangExposed’s response posts:

Figure 15: Response from [UK_Daniel_Card/mRr3b00T, highlighting concerns about GangExposed’s conduct.

I must now address GangExposed’s response regarding his alleged extortion of a cybercriminal. He stated, “The screenshots you published in your article – I confirm their authenticity” and continued with “I’ll tell you more, Devman eventually paid. He himself proposed to “make peace,” but I insisted on a principled condition: “pay any amount, even 1 satoshi.” He paid about $5, or thereabouts. For me it was a matter of principle. The amount didn’t matter.”

I have been doing this work for a long time. Not once have I demanded or accepted money from a threat actor, regardless of the amount. In the conversation between GangExposed and Devman, GangExposed tells him, “Pay, I’ll share real info. I won’t help you for free anymore” and “I’m not playing with you now. I made an offer, what happens next is up to you.”

None of this fits the profile of a researcher. It does, however, fit the profile of a threat actor and reminds me of many criminal actors I have engaged with over the years. His escalation and anger only grow with each post, and he feels the need to justify his actions and criticize mine, which is his prerogative. No matter what he thinks of my work, I cannot and will not ever condone the use of illegal practices, such as extortion, as a practice conducted for research purposes, nor do I believe this was part of his “operational play”.

GangExposed is entitled to his opinion of me and Analyst1. However, our research supports the greater community, aids law enforcement operations, and has been used to support indictments of cybercriminals. I stand by our high-quality investigations into the individuals behind these attacks and the intelligence we provide to help better defend against and mitigate criminal activity.

[End of Update]

With the GangExposed matter addressed, I return to the primary focus of this investigation: Devman himself. Beyond the allegations, leaked conversations, and technical artifacts, I sought to understand his operation, motivations, and capabilities through direct dialogue.

The Interview

Though I regularly speak with Devman, I wanted a formal interview. This proved far more challenging than I expected. Since we have frequent conversations, I thought his responses would be thorough. We talk a lot, and Devman is usually not short on words. However, this format required him to sit and type out each response, resulting in answers with much less detail than I hoped for. Still, Devman did answer a few questions, which I’ll include for completeness.

- Jon: “Can you give me some background on your criminal Resume and confirm that you worked with Conti, Ransomhub, Dragon Force and then started your own operation?”

- Devman: “Yes I did work with conti and I did work with all of the guys mentioned above. This list is not full there where other non cybercrime moments I had in my life”

- Jon: “You had been operating Devman ransomware as a non-RaaS operation. What made you decide to change your operational model to a RaaS and what is your goal (benefit) in doing so?”

- Devman: “To many accesses around 2k weekly from a botnet”

- Jon: “What can you share with me about the post you have referencing an upcoming attack involving an attack on critical infrastructure?”

- Devman: “There will be something really bad that you would expect from a bad guy like me. Some one’s economy will be affected.”

- Jon: “Is there anything new with you operation or ransomware that separates you from you competition (SCADA ransomware, destructive ransomware)?”

- Devman: “Only time will say”

Devman’s cryptic responses and reluctance to provide technical details left critical gaps in understanding his operation. To validate his claims and assess the actual capabilities of his ransomware, I turned to independent technical analysis and threat intelligence sources.

The Technical Reality

ANY.RUN’s forensic analysis, published July 1, 2025, shows Devman’s malware shares large portions of code with DragonForce, including leftover strings and identifiers. The ransomware uses Windows Restart Manager abuse, identical ransom note format, and encryption inherited from the Conti lineage.

But the ransomware has bugs. Serious ones. Due to builder misconfiguration, the malware often encrypts its own ransom notes, making them inaccessible to victims. The naming produces files like e47qfsnz2trbkhnt.devman for the encrypted ransom note itself. The wallpaper-changing function works on Windows 10 but fails on Windows 11.

I asked Devman about this directly, and he claims this is no longer an issue and the problem was “taken care of”. He told me he no longer uses it and has developed a new variant “from scratch written in Rust”.

Operational Claims vs. Technical Reality

The gap between what Devman claims and what his malware actually demonstrates became more apparent in later conversations after the platform launched.

When I asked Devman about the high-value targets he wanted documented, he told me it was “one gas company” that would be “locked soon.” When pressed about location, he remained noncommittal—”Idk), he said, but this was evasion, not uncertainty. Someone planning an attack on specific infrastructure knows exactly where that infrastructure is and which populations depend on it. He simply wasn’t sharing operational details.

He explained they had developed a specialized SCADA locker for the target, designed to cause progressive physical damage beyond encryption. The malware would push industrial control systems beyond their operating parameters, processors, memory, and thermal limits, forcing systems to ramp up and run hot until hardware failed. The only way to stop the ongoing destructive cycle would be to pay the ransom for the decryption key.

Devman’s claims about targeting critical infrastructure cannot be independently verified. However, the targeting of energy infrastructure, whether power generation, transmission, natural gas processing, or distribution, represents precisely the kind of attack that cascades beyond a single victim. When energy systems go down, hospitals lose power, water treatment facilities shut down, traffic control fails, and entire regions lose essential services.

The conversations continued, but the operational considerations and ethical boundaries shifted with information like this, whether the specific threat was real or aspirational.

Conclusion

It has been two weeks since the platform launched. Victim listings continue to populate, negotiations proceed, and the infrastructure expands.

I received access five days before the public launch. I have spent months in encrypted conversations with the person running it, not just text messages, but voice calls, which are rare between researchers and active ransomware operators. Most threat intelligence relies on forum posts, leaked chats, and technical artifacts. Direct voice communication is unusual. Operators typically avoid it for OPSEC, but the HUMINT value exceeds the risk.

Those conversations documented the psychological cost he describes even as he made decisions that increase exposure. He understands consequences, the paranoia, the recognition that “you won’t have a happy end,” the awareness that crime means never seeing your kid. And yet, here we are, witnessing expansion instead of exit.

Operationally, the exposure calculus is straightforward. Every affiliate multiplies risk. Every piece of infrastructure creates forensic artifacts. Dual-wallet payments create repeatable blockchain patterns. He gave me early, pre-launch access, knowing I would document his activity. Voice calls add risk, and we both understand that.

We both engage anyway.

The 10,000 USD deposit makes infiltration harder for researchers and law enforcement, but it does not prevent an arrested affiliate from cooperating. The “provide 100 GB of exfiltrated data” requirement means each affiliate generates evidence before deploying ransomware. Recruitment is public. The rules are documented. Monitoring is continuous. The accumulation continues.

What remains unverified are the bugs he claims are “taken care of,” the SCADA/ICS locker mentioned privately, the availability of professional negotiators, and the gas company attack he described with claimed sophisticated SCADA capabilities. Time will tell whether these are real capabilities or aspirational claims to attract sophisticated affiliates.

What is verified: six months from affiliate to platform operator; modified DragonForce code with documented flaws; two older leak sites now offline with focus consolidated on the RaaS platform; active recruitment; a rulebook that permits critical-infrastructure and hospital operations while prohibiting child-related targets; commission tiers consistent with standard RaaS economics; and months of direct communication that reveal someone aware of the trap but unwilling or unable to step out of it.

I will keep watching. That is the arrangement. He operates, I document. We disagree about hospitals and critical infrastructure. The work continues on both sides.

About Analyst1

Threat intelligence teams often struggle to bridge the gap from insight to action. Analyst1 is the Orchestrated Threat Intelligence Platform designed to resolve this issue. It automatically organizes threat data, links it to your assets and vulnerabilities, and customizes views for different roles. Analyst1’s orchestration layer streamlines workflows and automates reliable actions by integrating with SIEM, ticketing, and vulnerability management systems. From Fortune 500 financial institutions to national security agencies, enterprises trust Analyst1 to unify their defenses, significantly reducing their response time from days to minutes.

.png)