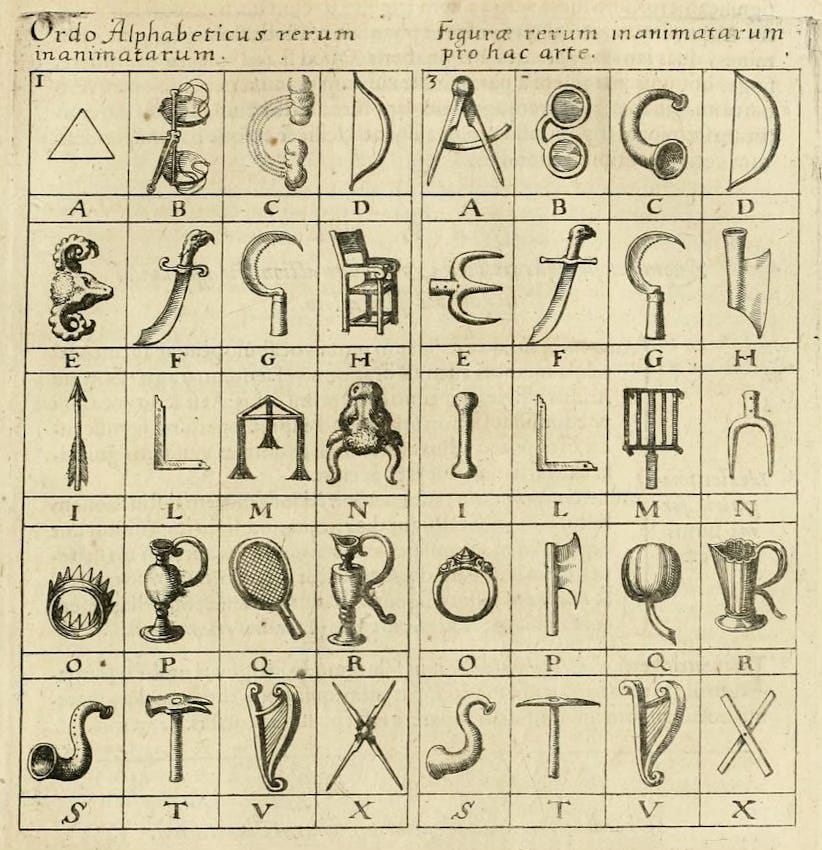

Robert Fludd, from Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia (1617)

In conversation with Mariana Dimópulos

In my case, descended from Germanized Poles on my mother’s side and Dutch-speaking settlers in South Africa on my father’s, I grew up in Cape Town in an environment where English—the master tongue—seemed to be the way of the future, and an English-language education the best way of ensuring that a child would prosper. Both of my parents had their schooling in English, and learned to read and write English better than they read or wrote Afrikaans.

The language of schooling remained an intensely political issue. By the time I arrived on the scene in the 1940s, the reactionary Afrikaner nationalist movement was on the point of taking over political power. The current that had borne so many Afrikaans speakers into anglophony began to be reversed; and a cohort of children like myself was left stranded, at home neither among the Afrikaner-nationalist majority nor among the suddenly powerless Anglo minority.

The phenomenon of which I was an instance—the child who masters the English language but is not a member of the Anglo culture—was not uncommon across British colonies in Africa and Asia. As British control weakened and withdrew after 1945, significant minorities were left behind: middle-class “natives” who, attracted by the material advancement promised by British-dominated commerce and government, had done their best to anglicize themselves. Even in their isolated position in the newly independent nations, such minorities continued to feel they belonged to a worldwide Anglo culture, whose center was perhaps now the United States rather than Britain.

As a child at school I found that I was “good at” English. I seemed to have an intuitive feel for the language. At the age of seventeen I enrolled to study mathematics at the University of Cape Town, but also took courses in Latin and in the subject called “English Language and Literature.” Founded on the values of British Liberalism, the University of Cape Town was the institutional embodiment of a belief, so deep that it barely needed to be articulated, in Progress: humankind was on a progressive historical trajectory, and by a decree of divine Providence the British race had been entrusted with leading that upward drive. In my courses in English I competed successfully with Anglo South African classmates: I knew their language, it seemed, as well as they did. After graduating I went to live and work in London, heart of the old Empire. I adapted my colonial way of speaking and my colonial manners; with my white skin I could soon pass undetected in the crowd.

After years in England I moved on to the United States to continue my education in the humanities. I graduated with a doctorate and returned to South Africa, where I was hired to teach English language and literature at the same institution whose portals I had entered as a student fifteen years before. There was a certain historical irony in this return: with not a drop of English blood in my veins, and with an abiding skepticism about the ideology of Progress, I was being entrusted with conveying the values enshrined in the English language and its literature to the sons and daughters of Anglo South Africa.

I became a writer too, an “English” writer in the sense that I wrote in the English language, though—as you said earlier—I treated the language as if it were foreign to me. I wrote novels, which were published in New York and London, the twin centers of English-language publishing. Since I was neither American nor British, my books were listed in their catalogues under the catch-all title “World Literature.”

I was also widely translated, at a time in history when many more books were translated out of English than into English. Why was this so? The answer I received from the industry—that English speakers were on the whole not curious about the “outside” world—was only partly true. A fuller answer would have been that English speakers could afford to be indifferent to the outside world, whereas the outside world could not afford to ignore the Anglo world, and in particular the United States. Thus it was only natural that foreigners should want to translate books from the Anglosphere into their own languages; whereas to be translated from a foreign language into English was a mark of distinction. As the United States had become master of the world, so the language of the United States had become the language of the world. One could travel the globe and “get by” with English. Foreigners learned to speak English, that was the rule; it was not really necessary for Anglos to learn foreign languages.

I visited Iceland and in Reykjavik met two adolescent boys, sons of my host, who told me, in excellent English, that they disliked their native Icelandic: the language was too difficult and anyway had no future. The future belonged to English. They sounded to me as I must have sounded a generation earlier. Perhaps they too would end up as professors of English.

At more or less the same moment I began to question my position in the system, as an assimilated foreigner whose very mastery of the master language seemed to confirm that it was only natural that English should rule the world. I had always felt foreign in Anglo culture, felt like an imposter. Now the language I spoke and wrote—spoke and wrote so well that it could have been mistaken for my mother tongue—began to feel foreign too. Foreign to me, and foreign to Africa too, where it had never taken root, had never tried to take root, had remained the language of the masters from across the seas. The language of my books began to take on a more abstract quality. I had lost interest in sounding like a native—that is, a native English speaker.

What was going on? I told myself I was feeling my way towards a rootless language, a language divorced from any sociocultural home. If I had known Esperanto, if I had been confident that Esperanto had the expressive resources I needed, I might at that moment have turned to writing in Esperanto.

I first met you when, for an anthology I was preparing, you translated some stories by Robert Musil from German into Spanish. At the same time, with the backing of our sympathetic Argentine publisher, Maria Soledad Costantini, I was embarking on a series of collaborations, initially with Elena Marengo, then with you, turning English texts that I had written into Spanish texts that were intended to carry no marks of a secondary status: where my English proved recalcitrant to Spanish reformulation, it was the English that had to give way and be rewritten.

It was no accident that these collaborative books were published first in Argentina, then later on in Australia, two countries of the southern hemisphere. (I call it the southern hemisphere, not the Global South, a term I avoid.) They appeared first in Spanish, just as the afterworld in which my three Jesus novels are situated is a Spanish-speaking afterworld—Spanish-speaking not because I think Spanish is in some sense “better” than English, but simply because Spanish is viable as an alternative to English (also because I thought it would give a jolt to Anglo readers to find that the language of the afterlife would not be English). These collaborative texts appeared first in Spanish, and they appeared first in the southern hemisphere. Thus they did not first have to pass the scrutiny of the gatekeepers of the North (editors, reviewers) before they could be read in the South …

Read Part Two of this post here

J. M. Coetzee is the author of more than twenty books, including The Pole; Waiting for the Barbarians; Life and Times of Michael K; Boyhood: Scenes from a Provincial Life; and several essay collections. In 2003, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. This post is adapted from Speaking in Tongues, his new book in conversation with Mariana Dimópulos, an Argentine writer, translator, and teacher specializing in German philosophy, who translated his novel The Pole into Spanish.

Read Joy Williams on J. M. Coetzee’s three Jesus novels.

More in Book Post on translation:

The trials of publishing in translation

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on writing in small languages

Thea Lenarduzzi on dialect and the familial past

Maryse Condé on the elusive language of home

Please consider gathering a few pennies to come to the aid of an arts organization that means something to you and has lost its NEA funding. There is a list here of those whose grants were terminated.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review delivery service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Some Book Post writers: Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, Jamaica Kincaid, Marina Warner, Lawrence Jackson, John Banville, Álvaro Enrigue, Nicholson Baker, Kim Ghattas, Michael Robbins, more.

Community Bookstore and its sibling Terrace Books, in Park Slope and Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn, are Book Post’s current partner bookstores. Read our profile of them here. We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at our partner bookstore during our partnership. To claim your subscription send your receipt to [email protected].

If you liked this piece, please share and help us to grow, and tell the author with a “like”

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

.png)