This article’s headline might seem like clickbait, I realize, but I couldn’t think of a snappier summary of what I’m discussing today. I’ve been looking through the documents surrounding the 1994 lawsuit in which Capcom alleged that Data East’s one-on-one martial combat game Fighter’s History ripped off Street Fighter II. And while I’ve found a few video game history gems buried in these legal papers, the most interesting document so far would have to be a deposition given by Akira Nishitani, co-designer of Street Fighter II, in which he claims that the game’s characters are not inspired by other sources, including video games and comic books.

Street Fighter’s Chun-Li vs. Fighter’s History’s Feilin.

If you’re even marginally aware of the Street Fighter series, you could probably guess that this claim is quite likely false, to the point that it might be surprising that there is a legal document in which Nishitani claims this “under penalty of perjury under the laws of the United States.” Granted, Nishitani gave his statement in Osaka, for whatever that’s worth, but there’s a substantial amount of research out there — and on this website — showing that much of the core Street Fighter II cast was drawn from other sources, including real-life martial artists, movies, comics (both manga and western) and other video games. And I’ll summarize all that in this piece, but I should also clarify that this is not my attempt to nail a beloved video game creator thirty years after the fact. No, I’m more interested in understanding why Nishitani would make such a claim and how the nuances of inspiration might have led to Capcom thinking that Data East’s game ripped theirs off.

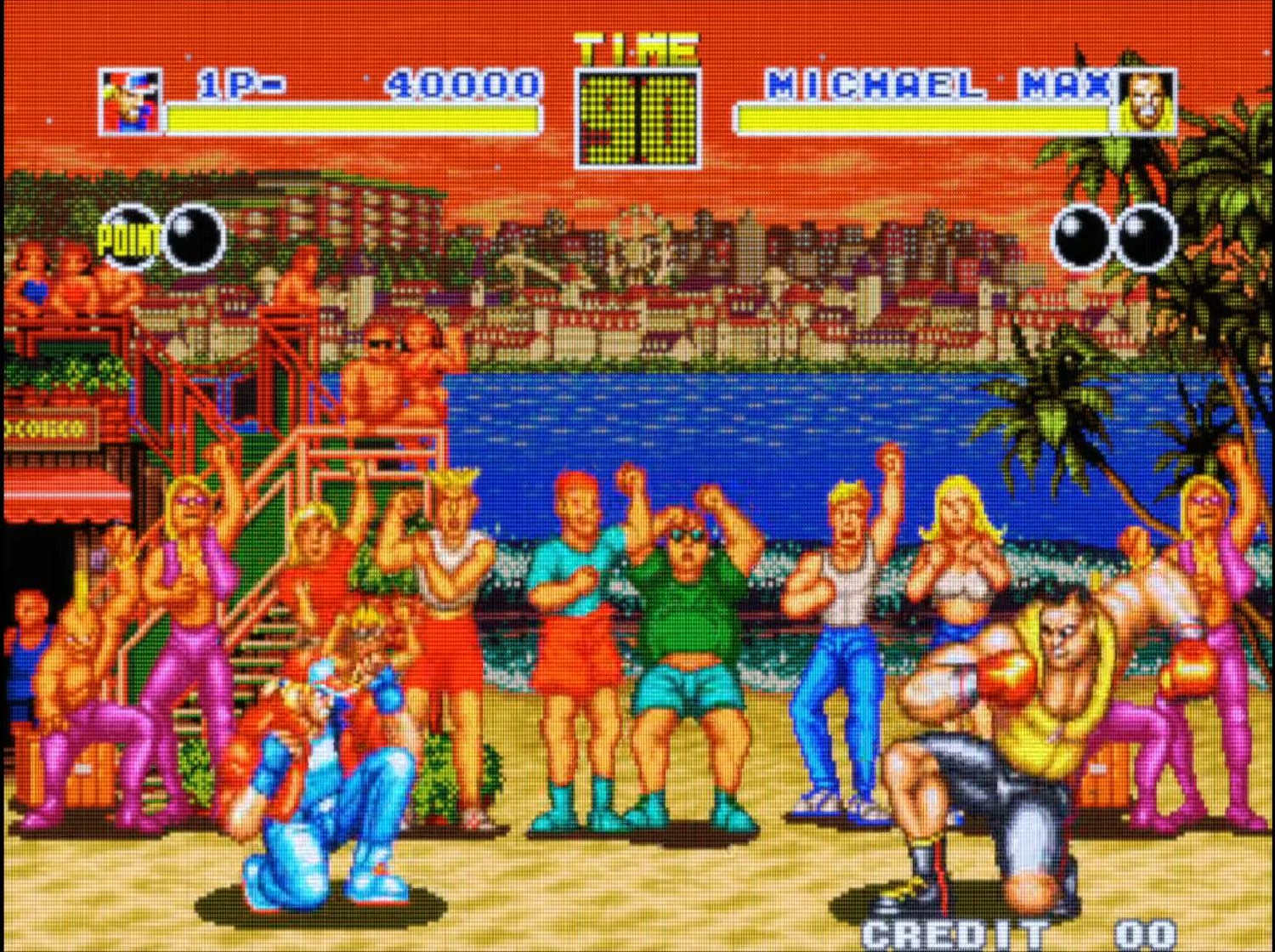

In case you’re not clear what I’m talking about, here’s a Cliffs Notes summary of the whole thing. Capcom’s Street Fighter II hit arcades in March 1991, and its blockbuster success inspired many imitators that also wanted to cash in on the concept of fighters from countries all over the world convening and kicking the crap out of each other. Fatal Fury, for example, hit arcades in November 1991, and although you could argue superficial similarities, it wasn’t labeled a ripoff, both because it followed so quickly on the heels of SFII that it seemed to be developed concurrently and because it was designed by Takashi Nishiyama, who’d co-created the first Street Fighter.

Terry Bogard (not Ken) vs. Michael Max (not Balrog) in the first Final Fight game, via.

In a sense, Fatal Fury almost plays like a follow-up to the first Street Fighter, doing less to reinvent the genre than Street Fighter II did. (Plus there’s the fact that Fatal Fury’s lead character, Terry Bogard, makes a covert cameo in Street Fighter I, making his official introduction to the series in Street Fighter 6 seem a little less out of left field.)

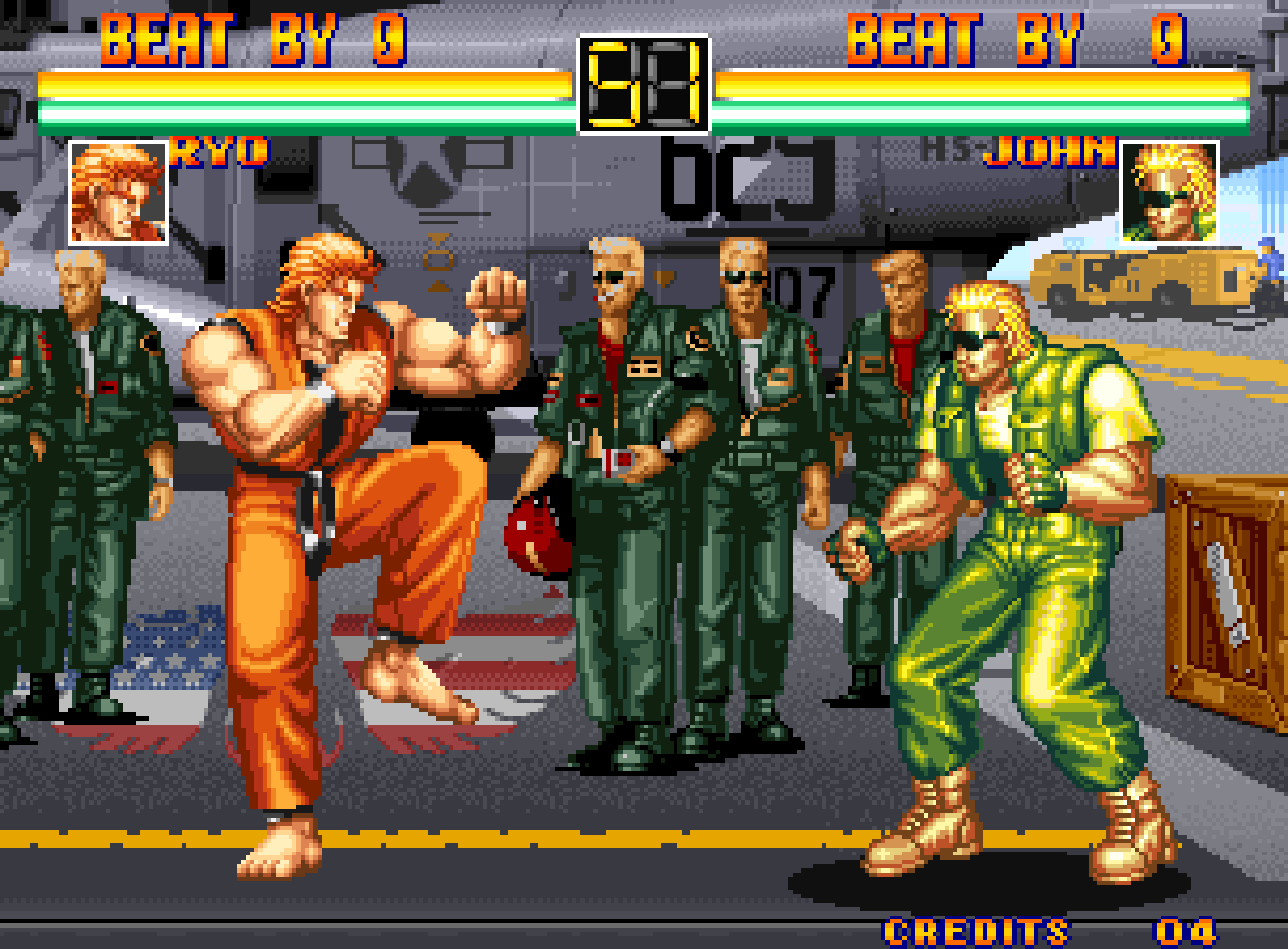

You could argue a similar case for Fatal Fury’s sister series, Art of Fighting.

Ryo (not Ryu) vs. John Crawley (not Guile) in the first Art of Fighting, via.

That game’s director, Hiroshi Matsumoto, happened to be the other co-creator of the original Street Fighter, and while the Street Fighter series would eventually introduce the character Dan Hibiki as a parody of Art of Fighting’s leads, Ryo Sakazaki and Robert Garcia, nothing about this title so irked Capcom’s legal team that a lawsuit resulted.

Fighter’s History, released by Data East in March 1993, did capture Capcom’s attention — and not in a good way.

Marstorius (not Zangief) vs. Ray (not Ken) in Fighter’s History, via.

Fighter’s History shared all the gameplay basics seen in Street Fighter II but also Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting and countless other one-on-one fighters from this era. In the eyes of Capcom’s legal team, however, Fighter’s History did less to distinguish itself from the source material. In September 1993, Capcom filed a civil suit in both Japan and the United States claiming that Fighter’s History violated copyright. As such, Capcom sought to stop the distribution of the title in arcades, in addition to 623 million yen in damages. I explain some of this background in this post, but all you really need to know to understand this matter is that despite what might seem like a lot of evidence in Capcom’s favor, the matter resolved in October 1994 with Judge William Orrick ruling that whatever Data East had copied from Street Fighter II was not protected by copyright. That’s not to say that Fighter’s History wasn’t derivative of Street Fighter II or even more derivative of it than other one-on-one fighters from back in the day — just that the judge didn’t think Capcom had a legal claim to the elements it brought up in court. As a result, Fighter’s History got to continue existing, even if it never stood a chance of dethroning Street Fighter, which is alive and well today.

My background as a reporter was mostly with criminal court cases, not civil, so I don’t really know if the 442 documents included in the case file for Capcom USA, Inc. v. Data East Corp., et al, is more than average. But regardless I have to thank Aaron Greenspan for replying to my query on Bluesky and pointing me toward Plainsite.org, which proved invaluable in getting ahold of the actual court documents for this post. To a degree, I had to make some educated guesses as to which ones would have anything interesting in them, and everything I received is currently posted at the Video Game History Foundation’s digital document archive. I’ve requested more, to be covered in a future post, and those will be shared as well. It’s entirely possible that a fresh set of eyes will be able to spot something that I missed. As far as I know, a lot of what’s buried in these court documents is not widely known among gaming historians and is not currently easily available online. There is a lot here!

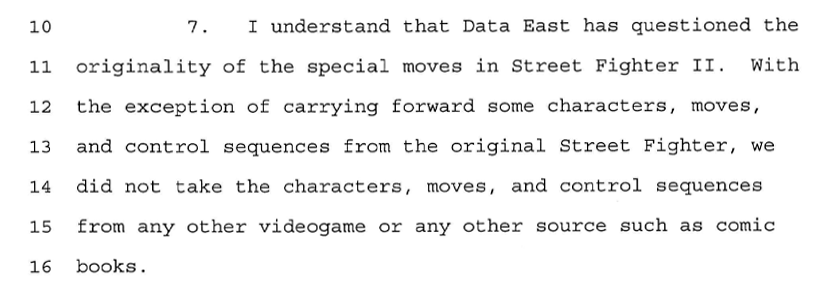

But foremost among all the bits in the documents I received is Nishitani’s claim that Street Fighter is innocent of any kind of intellectual borrowing, at least on the level of what Capcom claimed Data East had done.

Here’s the full quote:

I understand that Data East has questioned the originality of the special moves in Street Fighter II. With the exception of carrying forward some characters, moves, and control sequences from the original Street Fighter, we did not take the characters, moves, and control sequences from any other videogame or any other source such as comic books.

This, I have to say, is a rather ballsy boast on Nishitani’s part and perhaps a strategic one, given the nature of the civil suit against Data East. But it’s not difficult to find ways in which this claim seems false. The most obvious piece of evidence to the contrary is probably Street Fighter II’s boxer character, known in the English localization as Balrog but as M. Bison in Japan. I explain this in greater detail in this post, but the long and short of it is that Capcom rotated the names of three of the four boss characters; the boxer became Balrog, the Spanish matador became Vega, and the evil dictator big bad became M. Bison. Why rotate the names instead of just naming the boxer character? Because all the voice samples had been recorded for the Japanese version of the game, and this fix allowed Capcom to skip out on paying for the announcer actor to say that new name. So yeah, fiscal solvency is the reason we English-speaking Street Fighter fans have an evil dictator big bad who’s named after a herbivorous bovine.

In a roundtable discussion about the series celebrating the fifteenth anniversary of Street Fighter II, it’s mentioned explicitly — although not by Nishitani — that the boss name do-see-do was done to avoid a potential lawsuit from real-life boxer Mike Tyson, on whom Balrog was based. However, in a 1991 Gamest magazine special on Street Fighter II, Nishitani claims the rotation was motivated by the fact that the name Vega would sound feminine to westerners, but he follows up with a less committal remark about Mike Tyson, saying only, “Well, Bison is too similar to Tyson, and we could get into trouble. Things can be pretty strict over there.”

That’s not exactly an admission on Nishitani’s part that the similarities were intentional, but in the same section of the interview, he also claims Dhalsim was inspired by Dhaslima, “an actual fighter from the India-Pakistan area,” and then also remarks on a vague connection between Dhalsim and some unnamed comic book: “I had planned to make Dhalsim’s limbs longer from the beginning. … The artist is a big fan of comics, and I think he was influenced by that.” In 2014, Polygon’s amazing oral history of Street Fighter II would identify JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure as the inspiration for Dhalsim’s stretchy limbs, and although it’s not explicitly named, the reference is presumably to the Ripple technique Zoom Punch.

The list of outside sources that influenced the Street Fighter II characters and their moves doesn’t end there. For example, we have Capcom sources on the record admitting that Guile’s name was came from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, even if the story states that this only came about because it was pointed out after the fact that Guile’s design looked like the JoJo character, not that Guile was designed as a homage, the way Rose from Street Fighter Alpha seems specifically to evoke the JoJo character Lisa Lisa. Though I’m not sure that anyone at Capcom has confirmed it, Zangief’s name seems like an unmistakable reference to the real-life Soviet wrestler Victor Zangiev. In 2003, Capcom artist Akira “Akiman” Yasuda claimed that the original inspiration for Chun-Li was the Chinese character Tao from the 1983 anime Harmagedon: Genma Wars. And in my post about the mysterious origins of Blanka’s name, I noted that Yasuda cited the Nintendo title Pro Wrestling as at least a partial inspiration for the green beastman character.

Check out the big Blanka post for more info, but basically Pro Wrestling features The Amazon, a green, Creature from the Black Lagoon-type character, and one of his special moves — which Yasuda specifically recalls Nishitani using on him, is a vicious head bite, just as Blanka does in Street Fighter II. A winner is you!

But while this seem like decent enough evidence that Street Fighter II’s cast drew inspiration from various sources, I wonder if it’s possible that Nishitani is not lying so much as underscoring a radically different philosophy underpinning Capcom’s creative efforts that, at least in his eyes, was lacking in Data East’s. It is worth noting that per the documents, Capcom’s central complaint was that Data East had copied several elements from Street Fighter II, including moves, and based on the documents I read, the suit seems more focused on the moves — how they look on screen and the controller inputs needed to make them — than they were on the characters doing them.

Capcom’s choice of emphasis may have been a mistake, given the judge’s final ruling in this case, but in an effort to get to the bottom of what Nishitani meant in his deposition, here is a breakdown of some of the more interesting points of dispute that I found in reading through the court documents.

In support of the notion of not being inspired by outside sources, Capcom attempts to rebut Data East’s claim that the various Street Fighter II characters drew their special moves from the specific martial arts they practice. According to one of the documents in the cache, “Capcom’s Response to Data East’s Statement of Material Facts Not in Dispute” (April 28, 1994), Capcom’s take is that “these fantastic, non-reality-based special moves are extremely important to the look, feel, and play of the game, since they ‘distinguish the character from other characters’ and give each character its ‘flavor’ and its ‘edge.’”

There’s a point that comes up more than once that I think may be introduced in an earlier document, but it involves the idea of whether the expression of chi can do more than just create “different hologram images.” From context I gathered that this pertains to the way fireballs appear on screen and whether aesthetic differences work as points in favor of or against plagiarism. Whatever the case, I love that this was a matter that came before a U.S. courtroom, and Judge William Orrick had to learn about the metaphysics of chi expression in order to hear this case. Orrick was the judge who sentenced Patty Hearst back in 1976, among many other cases, and that’s why it amuses me that he had to consider the legal ramifications of the following sentence: “Magic projectiles may also be differentiated in many other ways, including their form, speed, range, and power; the complicated command sequences used to create these projectiles; their angle of delivery and location of impact; and their effect on the opposing character.”

In an apparent effort to prove that Capcom can’t hold a monopoly on projectile moves, the same document notes that a 1986 Data East title featured a character throwing balls well before Ryu did in the original Street Fighter. I’m not clear what game this could be. I’m guessing it could be Karnov, which actually debuted in 1987, and ironically enough the title character would end up being the final boss in Fighter’s History.

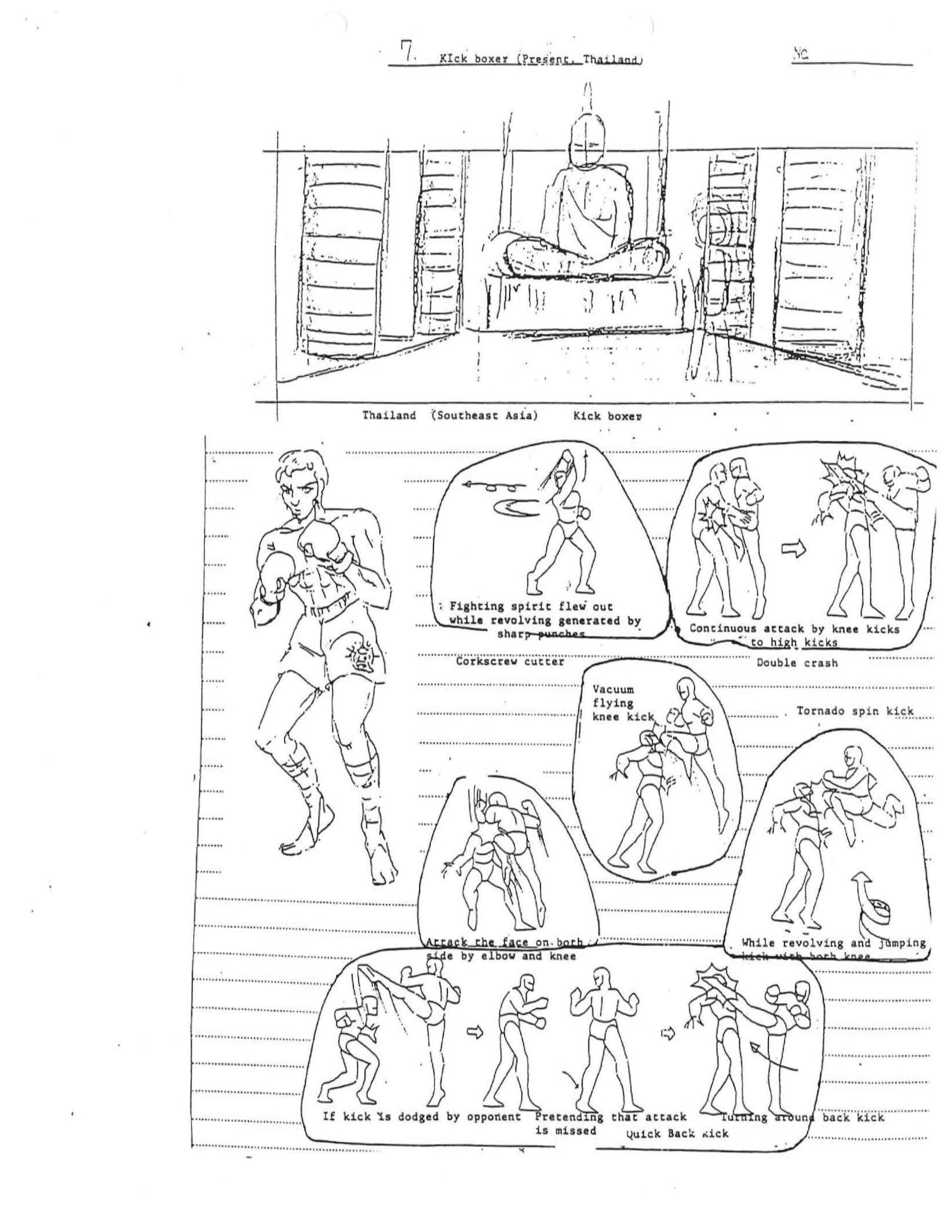

The documents show an effort on Capcom’s part to argue in favor of Fighter’s History character Samchay being a deliberate rip on Street Fighter II’s Sagat instead of their similarities being explained away by both of them being muay thai practitioners.

Sagat jumps forward farther than any actual kickboxer could jump, and his Tiger Knee hits twice when Sagat is sufficiently close, which is an idiosyncratic Street Fighter II feature. Sagat also jumps forward three different distances in response to complicated control sequences that do not correspond to any kickboxing moves. The ranges of Samchay’s copy of Sagat’s Tiger Knee are very similar to Sagat, and Samchay also copies Sagat’s idiosyncratic feature of hitting twice when he is sufficiently close.

Throughout the majority of these documents, I actually feel like Capcom is making the stronger argument, at least as far as enumerating the ways that Data East borrows from Street Fighter. One point on which I feel Capcom’s team falls short, however, is in articulating exactly how and when imitation crosses the line from something that demonstrates appreciation to something that is derivative in a bad way. At one point, Data East declares that none of the Fighter’s History characters is identical to any of the Street Fighter characters. Capcom agrees that this is true but then continues that this misses the point, saying, “The only material issue is whether the Fighter’s History characters are substantially similar to Street Fighter II characters.” But the difference between identical and substantially similar is never made clear enough, at least per my reading. Zangief and the big burly wrestler character in Fighter’s History, Marstorius, differ in “details of appearance,” for example, but “are substantially similar in their appearance, special moves, combination attacks, special controls, fighting styles, and other features.” Ditto Ken and Ray, the blond, American shotoclone-type Fighter’s History character, as well as Guile and Matlock, a British punk character that Capcom thought was too similar to Guile. I’m not a lawyer, but the difference between appearance and “details of appearance” is lost on me in a way that undermines Capcom’s point.

Capcom also muddies the water when it steps away from the one-to-one character comparisons and argues instead that other, dissimilar Fighter’s History characters seem to have inherited special moves from Street Fighter. For example, there is a section in which Capcom accuses Feilin, the alleged Chun-Li clone, of having stolen Guile’s signature Flash Kick move which in Street Fighter has him flipping in the air with an arching kick that is useful for deterring aerial attacks.

As Capcom puts it, Feilin has one of these too — the text refers to it as a Flash Punch, but it’s officially called the Double Swan Punch — and the inputs are basically the same: charging down on the joystick, then hitting up and a punch, rather than up and a kick as you would with Guile’s move. And while I can understand Capcom’s argument that Data East essentially lifted a specific move that originated in Street Fighter II, the very fact that it was given to a character who was not the Guile analogue and done with a punch rather than a kick undercuts Capcom’s point, because they’re basically admitting that Data East did more than base-level copying. For what it’s worth, Guile’s move has since been rebranded the Somersault Kick, and imitations have appeared in Fatal Fury 2 (with Kim Kaphwan’s Flying Swallow Slash), in King of Fighters (with Ash Crimson’s Nivose) and many other games. Killer Instinct’s Cinder has a move that works similarly, for example, but with a different input. In a deposition from Andrew Cockburn, a then-nineteen-year-old working as an editor at Diehard Gamefan magazine, it’s not just the function of the move on its own that should arouse suspicion but also the fact that one of Guile’s notable Street Fighter II combos involving the move also works for Feilin.

The three basic attacks in Guile’s [combo] are a jumping fierce punch, a crouching jab, and a Flash Kick special move. This combination requires six commands that must be executed with precise timing. Feilin’s Flash Punch combination involves the same three attacks, the same commands, and the same precise timing, except that Feilin executes a Flash Punch instead of a Flash Kick, which requires use of a punch button as the sixth step.

Cockburn lists other examples, but the gist of his argument is that the existence of combos in Fighter’s History that previously existed in Street Fighter II indicates a calculated level of imitation, especially because combos were not an aspect that was programmed into Street Fighter II so much as a bug that players discovered once the game was in arcades. Of course, I’m also amused that Judge Orrick had to be taught the intricacies of fighting game combos, and I wish he were still alive so I could ask him how any of this landed back in the day.

In my previous post on the Street Fighter-Fighter’s History lawsuit, I pointed out my surprise that Capcom found Matlok to be derivative of Guile and not Jean-Pierre, the French gymnast character, who I think looks more like Guile despite his lack of vertical hair. One of Capcom’s complaints, however, was that Jean-Pierre’s projectile looked suspiciously like Guile’s Sonic Boom, just with a rose icon added to it. But Capcom also implicates Matlok as well, noting, “Indeed, Data East itself characterized Jean’s Bal Rose as ‘similar’ to Matlok's Spinning Wave, which is clearly a copy of Guile’s Sonic Boom.” The documents later go on to accuse Jean-Pierre as playing too similarly to Vega, which I suppose I can see, but again, just the fact that Data East would be apportioning out “stolen” Street Fighter II moves across multiple Fighter’s History characters would seem to indicate that what’s going on here amounts to something more creative than wholesale copying — a remix, you might say.

Capcom even claims that Ryoko, a Fighter’s History character that has no Street Fighter II counterpart and who is based on the real-life female judoka Ryoko Tani, uses moves that belong to Street Fighter characters.

Fighter’s History’s Ryoko character is substantially similar to copyrighted Street Fighter II expression in her moves, combination attacks, controls, and other distinctive features. Ryoko has moves that are similar in their appearance, controls, and effect to Vega’s Tumbling Claw and Zangief’s Spinning Pile Driver.

I was surprised how often Capcom brings up Mortal Kombat II, although I suppose I shouldn’t be, given the context. In western arcades, at least, Mortal Kombat II was giving Street Fighter II a run for its quarters, and it is notable that it represents everything that Capcom says Fighter’s History does not. It’s a one-on-one fighter that apes neither the look, the feel or the play controls of Street Fighter, and according to Capcom’s lawyers, “Mortal Kombat II thus proves that it is possible to make an original fighting game in the Street Fighter II game that uses very different characters, special moves, and controls.” This comes up in a deposition by Glenn Rubenstein, a then-eighteen-year-old fighting game enthusiast who speaks in favor of Capcom’s claims.

Mortal Kombat II is the best proof that Data East did not have to copy Street Fighter II’s special command sequences. Like Street Fighter II, Mortal Kombat II uses complicated sequences of joystick movements and button controls to produce special moves assigned to each character. But the sequences used in Mortal Kombat II are very different from Street Fighter II. … I understand that Data East has claimed that Mortal Kombat II is a completely different type of game from Street Fighter II, and thus it does not prove that it is possible to make an original game in the Street Fighter II genre. I disagree. Mortal Kombat II certainly is different in its characters, special moves, controls, combinations, playing strategy, and overall “look and feel.” But it is definitely in the same genre as Street Fighter II and attracts the same type of fans. It is a one-on-one fight game, like Street Fighter II, with distinctive characters and special moves. Mortal Kombat II is regarded by players as a direct competitor of Street Fighter II, and is categorized as the same type of game.

Rubenstein comes back to Mortal Kombat II again in a drill-down on the mechanics and aesthetics of fireballs.

I understand that Data East has claimed that some similarity in the magic projectiles of Fighter’s History with those of Street Fighter II is inevitable, because there is no way to distinguish one projectile from another besides the “hologram” that is supposedly in the center of fireball projectiles. Again, Mortal Kombat II proves that this is wrong. Mortal Kombat II has magic projectiles that not only look different from Street Fighter II, but also use different controls and have a different strategic effect. For example, one character spits acid and another throws scythes. These projectiles are much faster than those in Street Fighter II, look completely different, are thrown in a different manner, use different controls, and hit the opposing character at a different place and in a different manner. Because of these differences, the strategy of using the projectiles in Mortal Kombat II is different from Street Fighter II.

One of the interesting (and less controversial) statements that Akira Nishitani makes during his deposition is that a key reason why Fighter’s History copies Street Fighter is that the controller inputs needed for special moves have no bearing on what they make the characters do; essentially, a player waggling the joystick in one direction or another to do one of these moves doesn’t reflect the moves the character does onscreen. For example, to make Guile execute his Sonic Boom projectile, the player must hold the joystick away from the opponent and then tilt it toward them while pressing the punch button, but there’s no corresponding backward movement that Guile does.

In designing the control sequence for Guile’s Sonic Boom, we did not intend for the movement of the joystick to the back position and then to the forward position to mirror the character’s arms as they draw back and then move forward. In fact, Guile does not draw his arms back. We selected the precise timing of holding the joystick in the back position (“charging”) as an arbitrary feature to fit our strategy for the move and character. Other sequences also do not fit the “natural flow” of the character’s body. For example, the control sequence for Ken's fireball is very different from Guile’s Sonic Boom, yet on the screen Ken draws his arms back and then moves them forward to release the fireball. Ken also does not crouch, even though the joystick moves through the crouch position.

What Capcom is attempting to argue here is that identical control inputs showing up in Fighter’s History means that Data East shamelessly copied Street Fighter’s controls in assigning them to similar moves. Capcom invented them, or so the lawyers argue, and there’s no other explanation for why they’d show up in an unrelated game. This is technically true, it overlooks the fact that the exact same input for Ken’s fireball move shows up in Fatal Fury, where an identical input makes Terry Bogard throw his Power Wave projectile, and Art of Fighting, where it makes Ryo throw his Ko-Ou Ken projectile.

Even more questionable is the fact that World Heroes, a fighting game released in 1992, developed and published by ADK, features a very Ryu and Ken-esque pair of palette swaps, Hanzou and Fuuma, who boast not only a fireball move that uses the same inputs but also a rising uppercut similar to the Shoryuken, also with the same inputs.

Hanzou (left) and Fuuma (right). Their fireballs may not look like Hadoukens on screen, but the control inputs to execute them are identical.

Capcom’s argument is also complicated by the fact that Guile’s Flash Kick move, which comes up more than once elsewhere in the documents, actually sort of does have him paralleling the control inputs. That move is done by charging down and then hitting up and a kick button, and Guile mirrors this in the game, crouching down in most circumstances before leaping upwards for the attack. This is the exception, but it’s nonetheless worth acknowledging that some Street Fighter II special moves do have the character reacting on screen to the “charge” portion.

Nishitani also rebuts Data East’s claim that various Street Fighter moves were based on real-life martial arts attacks.

I understand that Data East asserts in its summary judgment motion that seven moves from Street Fighter II are “standard” martial arts moves: Sagat’s Tiger Knee, E. Honda’s Knee Bash, Vega’s Air Throw, Vega’s Floor Slide, Balrog’s Dashing Punch, Zangief’s Backwards Throw, and Zangief’s Body Leap. In designing these moves, we did not attempt to duplicate standard moves. Rather, we created the moves with fanciful expression that would not be possible in real fighting moves. For example, we designed the positioning of Vega’s body as he sails along in the air and grabs the opponent in a way that would not be possible in real fighting, and we did not take the move from any particular realistic fighting style.

And then Nishitani goes for broke, alleging that games like Fighter’s History will bring about another video game crash, despite the fact that other games besides Fighter’s History seem to be biting Street Fighter. (For what it’s worth, Cockburn expresses a similar sentiment in his deposition.)

I think that games like Fighter’s History are bad for the video game industry. What video game players want are challenging games that offer something new and original. Fighter’s History does not. If Data East is allowed to continue to market Fighter’s History, it will encourage Data East and other companies to make rip-offs of successful and original games such as Street Fighter II, instead of investing the time and effort to make their own original games. The result will be that the arcades are flooded with imitations, with very few original games. The quality of video games will go down, and players will be discouraged from going to arcades. We will then be back where we were before Street Fighter II: the arcades will start dying again.

To be clear, Nishitani wasn’t wrong in that more blatant Street Fighter clones followed, but I’m not sure the proliferation of these types of games can be blamed for the contraction of the arcade industry that followed.

Finally, Capcom acknowledges that both Ryu and Mizoguchi, the Fighter’s History character claimed to be overly imitative of Ryu, are karate masters but then continues that that along does not account for the similarities, “including fantastic special moves that are not karate techniques, such as throwing a fireball and executing repeated kicks while moving forward in mid-air.” This is especially interesting in light of the fact that canonically Ryu is not a karate fighter; he never practiced karate (shotokan or otherwise) in Japan and only did in the English localizations of Street Fighter until Street Fighter IV.

Per my reading of the documents, these were the most interesting points from the lawsuit, in terms of how Capcom and Data East discussed their creative efforts and how anyone was discussing fighting games in a formal context back in 1993 and 1994.

As I mentioned earlier, most of these intricacies didn’t end up mattering, as Judge Orrick ruled in favor of Data East on grounds that “control sequences” couldn’t be protected, saying, “There were both functional and practical constraints that limited the range of expression available to game developers trying to design control sequences.” Orrick opined that five Fighter’s History moves were too similar to Street Fighter II ones that were, in fact, subject to copyright protection. (The text does not say which ones, however, and I hope to find this information in a future cache of documents.) As far as the Fighter’s History roster of characters, Orrick only found that three seemed overly similar to their Street Fighter II counterparts: Feilin, Ray and Matlok, who, as Orrick saw it, were too reminiscent of Chun-Li, Ken and Guile. Samchay, Mizoguchi and Marstrorius, he decided, “were more different than similar” to Sagat, Ryu and Zangief. Jean-Pierre and Vega are not mentioned at all.

But while Capcom did not end up persuading the judge that Data East had crossed a line, the impetus for this post was Nishitani’s claim that Street Fighter II characters were not borrowed from existing sources, the most relevant sentence of his deposition being “[We] did not take the characters, moves, and control sequences from any other videogame or any other source such as comic books.” Obviously, this does not seem to be true, to the point that I asked my translator, Fatimah, to double check the English translation. Fatimah says no, nothing was left out of the translation that makes it read any differently in the original Japanese. (The documents include the Japanese original as well as an English translation by Misako Maki Sack, a legal assistant at Morrison & Foerster, the law firm representing Capcom, which delightfully refers to itself as “MoFo,” as if that didn’t mean something else in English.)

So what do we think happened here?

Well, of course there is always the chance that Nishitani is fudging the boundaries of truth in service of the company he works for, I suppose. If this is the case, it’s perhaps of note that in 1995 he’d leave Capcom to form his own company, Arika, which would make the Street Fighter EX series for Capcom, which would later evolve into the Fighting Layer series independent of Street Fighter. But I really do think that regardless of the denotation of Nishitani’s statement, the connotation suggests something less black and white. There’s a reading of it in which Nishitani is not lying so much as inferring that what Data East did with Fighter’s History is a more egregious lifting of characters and concepts than what Capcom did in creating Street Fighter II. Obviously, pits and pieces of pop culture did work its way into the game, but I think it’s possible that Capcom would consider Street Fighter II a cobbling together of multiple influences with the intent of making them more than the sum of their parts. Conversely, what Capcom accuses Data East of doing is baser than that — more of a repurposing of a single character’s look and moveset in a way that approaches a one-to-one approximation. That is a generous reading, I’ll admit, and it’s loading a lot into Nishitani’s use of the word “take,” but I think it’s at least reflected often (if not wholly consistently) in how Capcom presents its case against Data East.

This reading falls apart, I suppose, when Capcom starts to point out alleged instances of copying where a Fighter’s History character might look like one Street Fighter character but include moves from another, but as I mentioned earlier, this is also where Capcom’s argument doesn’t work for me. And moving forward in the history of Street Fighter, you see more Capcom-created characters that seem to be more of a one-to-one approximation of something existing elsewhere. While this lawsuit was ongoing, for example, Capcom released Super Street Fighter II, which saw the introduction of Fei Long, who very much seems like a Bruce Lee homage without a whole lot more going on, though at least he’s a more flattering homage than Barlog was to Mike Tyson.

To answer the question posed in the headline of this piece, there is plenty of evidence that contradicts Nishitani’s statement that Capcom “did not take the characters, moves, and control sequences from any other videogame or any other source such as comic books.” But there’s also a *mostly* workable explanation for why he’s not necessarily lying, if you need there to be one. And I think that explanation might also help solve the mystery of why Capcom went after Data East but let every other Street Fighter II imitator slide.

Miscellaneous Notes

Scattered among the pages of text written specifically for the lawsuit are pieces of evidence proving the claims of one side or another. Included is an article from the Seattle Times that I could not find in digital form online, but it’s apparently in testament to the popularity of Chun-Li and, I suspect, to the fact that Feilin is an imitation of her. It’s all of six sentences long, but it kind of disproves the point because it repeatedly refers to her incorrectly as Chin Lu, which is kind of hilarious.

Long live Chin Lu! An inset from an August 17, 1993, feature in the Village Voice at least gets her name correct.

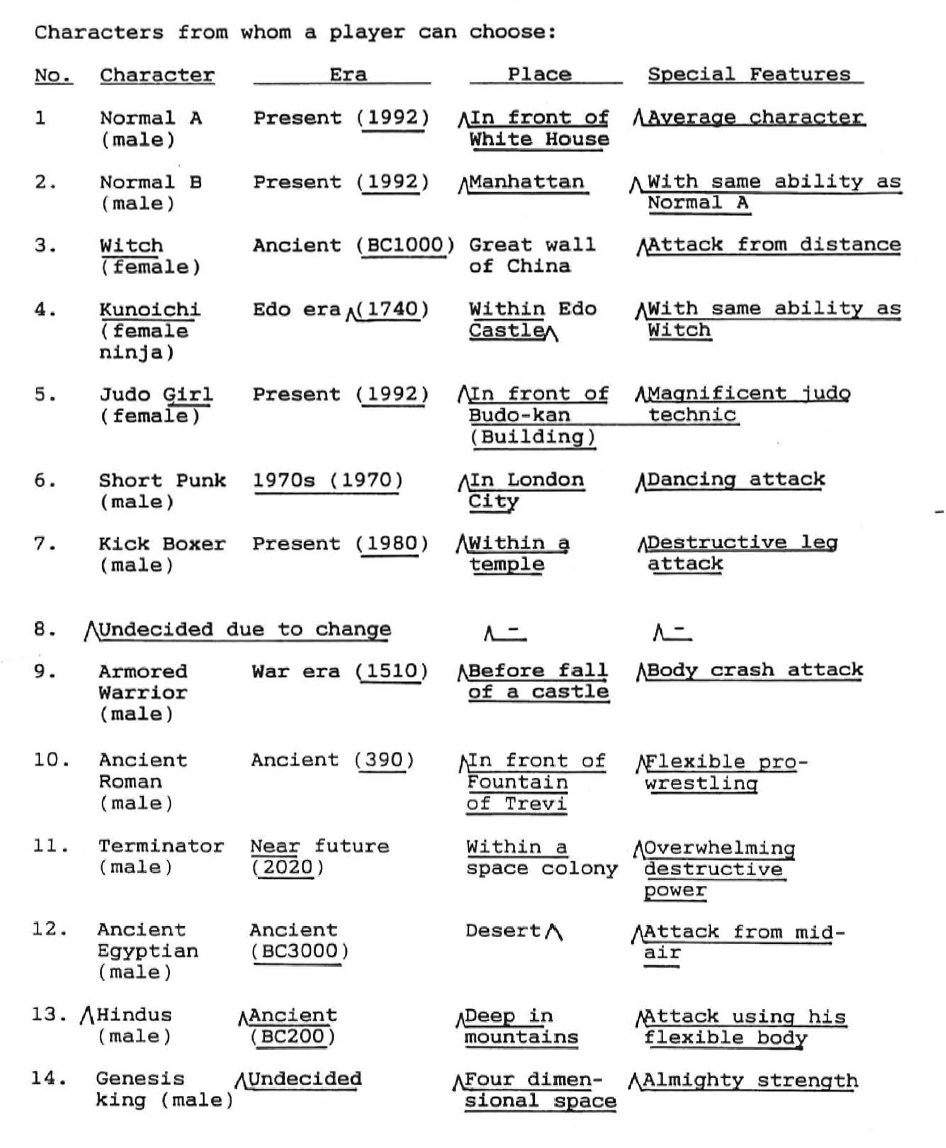

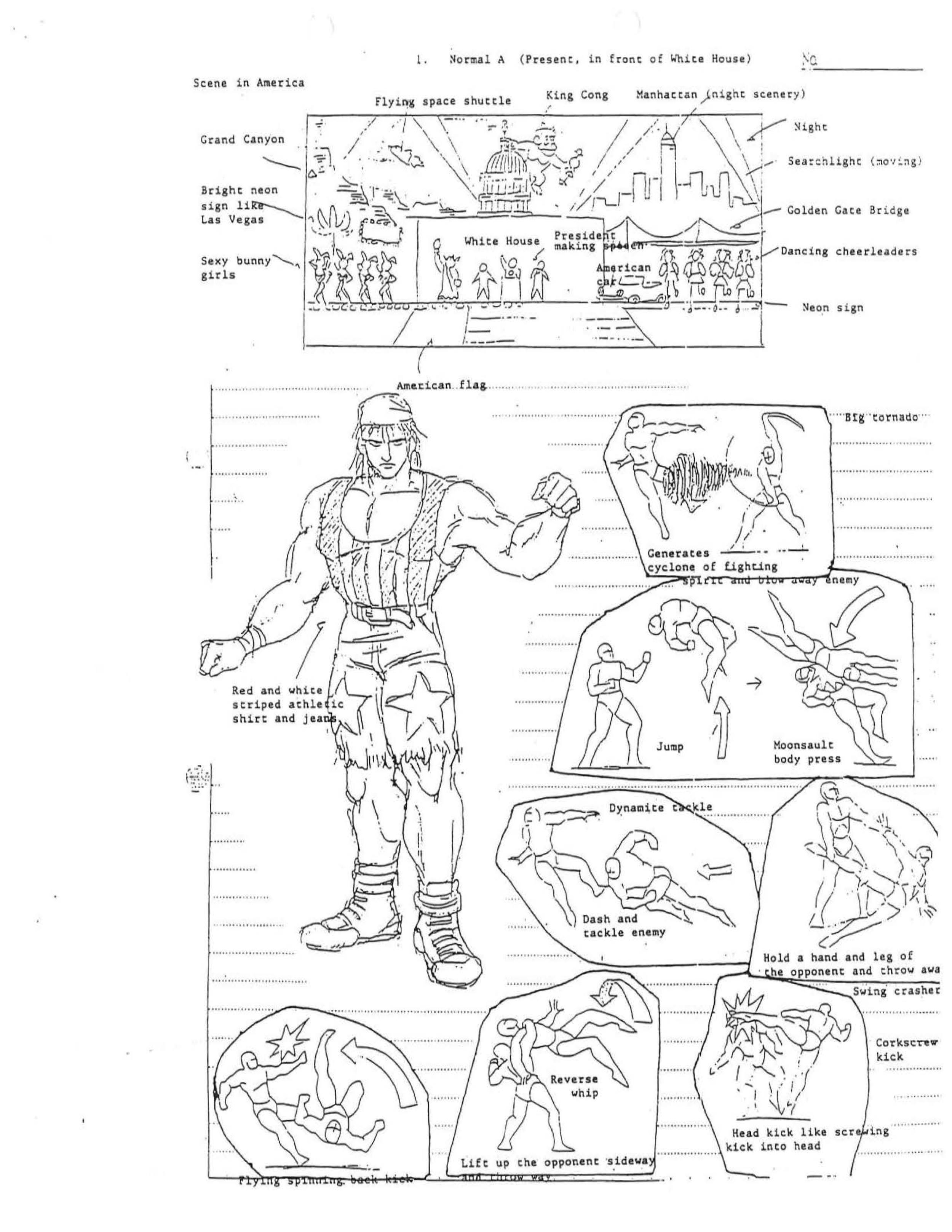

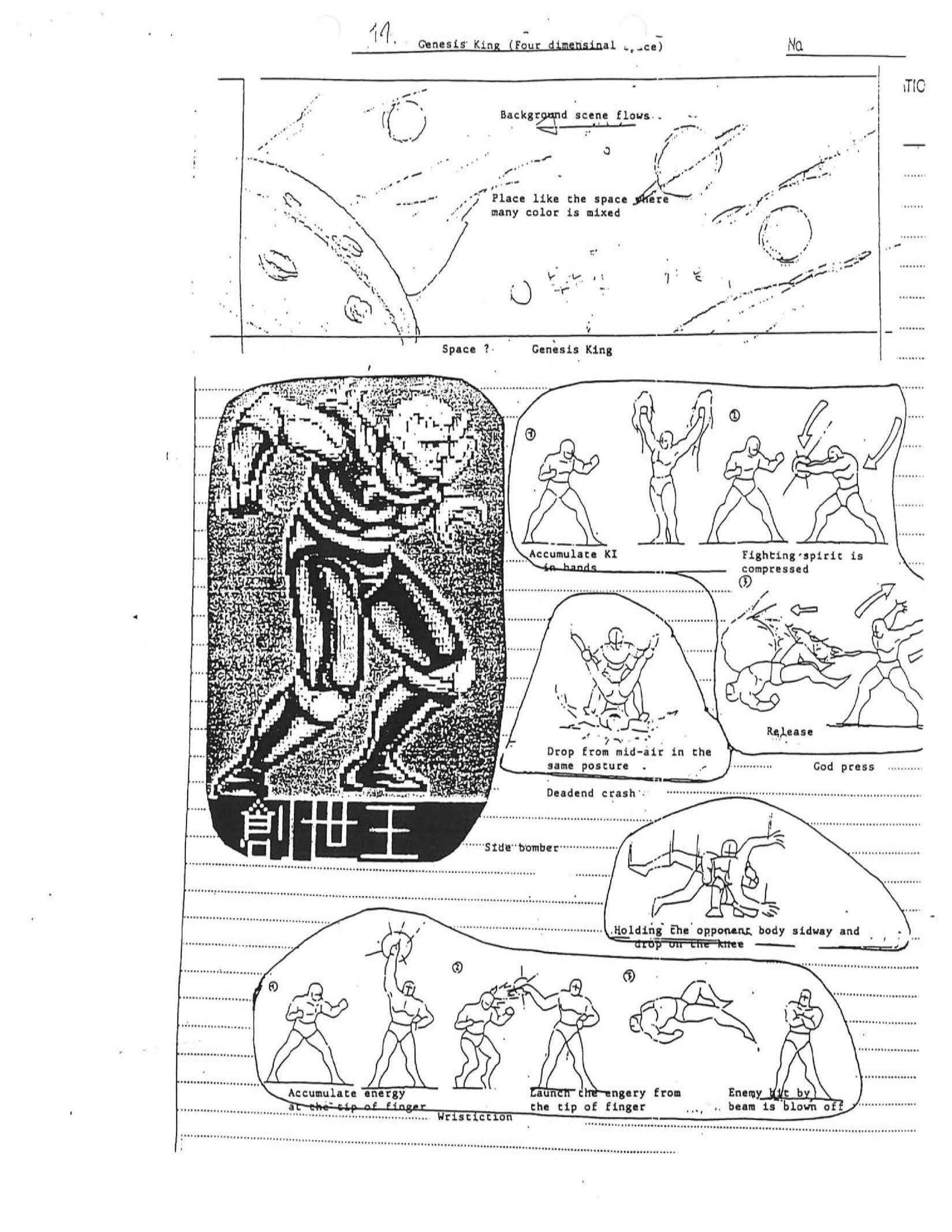

Also included is a December 1991 planning document for Fighter’s History that notes some remarkable changes between how the game was originally envisioned and what eventually hit arcades. The title initially bore the subtitle “War History — Fight Among the Strongest Warriors in History.” Most of interest to Capcom’s lawyers, however, is the fact that the outline describes Fighter’s History even in this early stage as a “Street Fighter II-type fighting game.” Almost immediately, however, the document attempts to differentiate Fighter’s History with a time travel-element that Street Fighter lacks. And while it would explain the origin of the game’s title, it would ultimately be dropped during the course of development. The original story pitch reads as follows, grammar unchanged for posterity:

A man called Genesis King who can travel between time suddenly appeared in the fourth dimensional world to search for “the strongest man in the history” …. And now, the fight on the scale of entire time and space among thirteen strong warriors he has gathered from various era and place is about to begin. This fight naturally is the fight using their flesh only; no weapons other than those released from one's body are allowed. Genesis King gave them means to time-travel and ordered them to fight in their own era. The last fight beyond history and space is about to begin. Who will survive his destiny and be the victor?

I just want to point out that Genesis King sounds more like a mean girl I went to high school with than a time-travelling supervillain, but whatever. More to the point, I guess, is that this set-up sounds remarkably similar to World Heroes, which debuted in arcades in 1992 and which also featured fighters from various time periods in addition to various geographic locations. It’s also not that different from Eternal Champions, released for the Sega Genesis in 1993, which also features fighters from different time periods, but they’re all dead so the mechanism through which they’re meeting each other is slightly different.

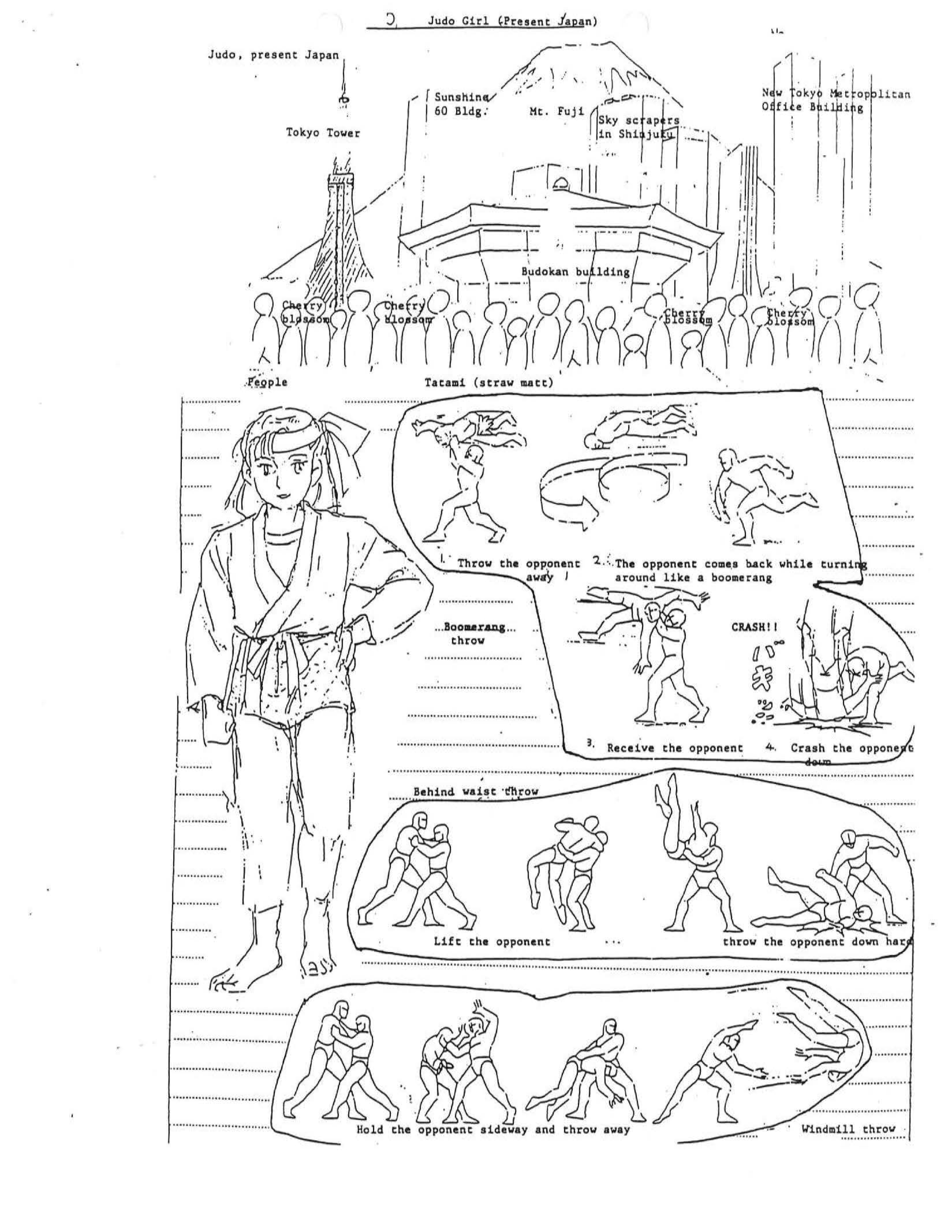

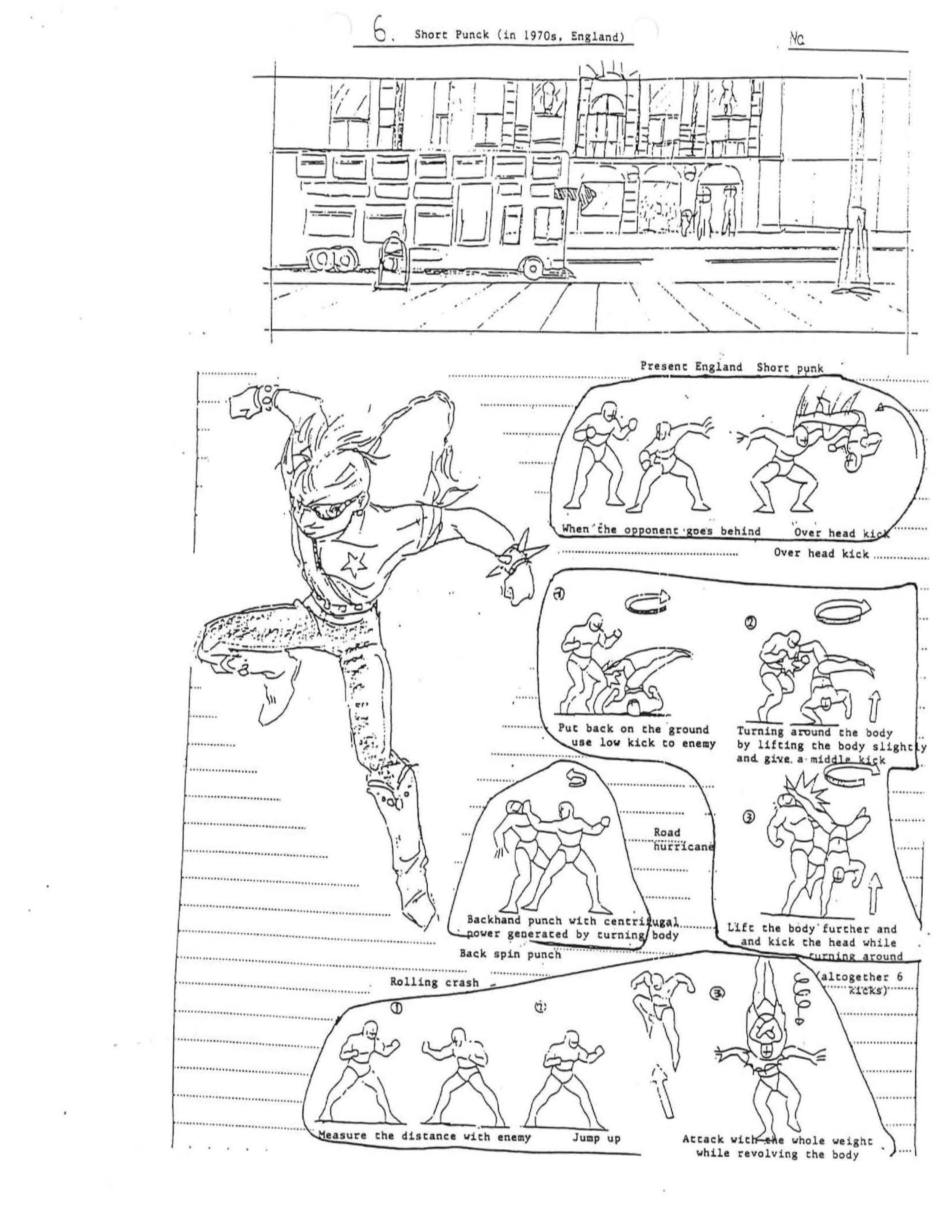

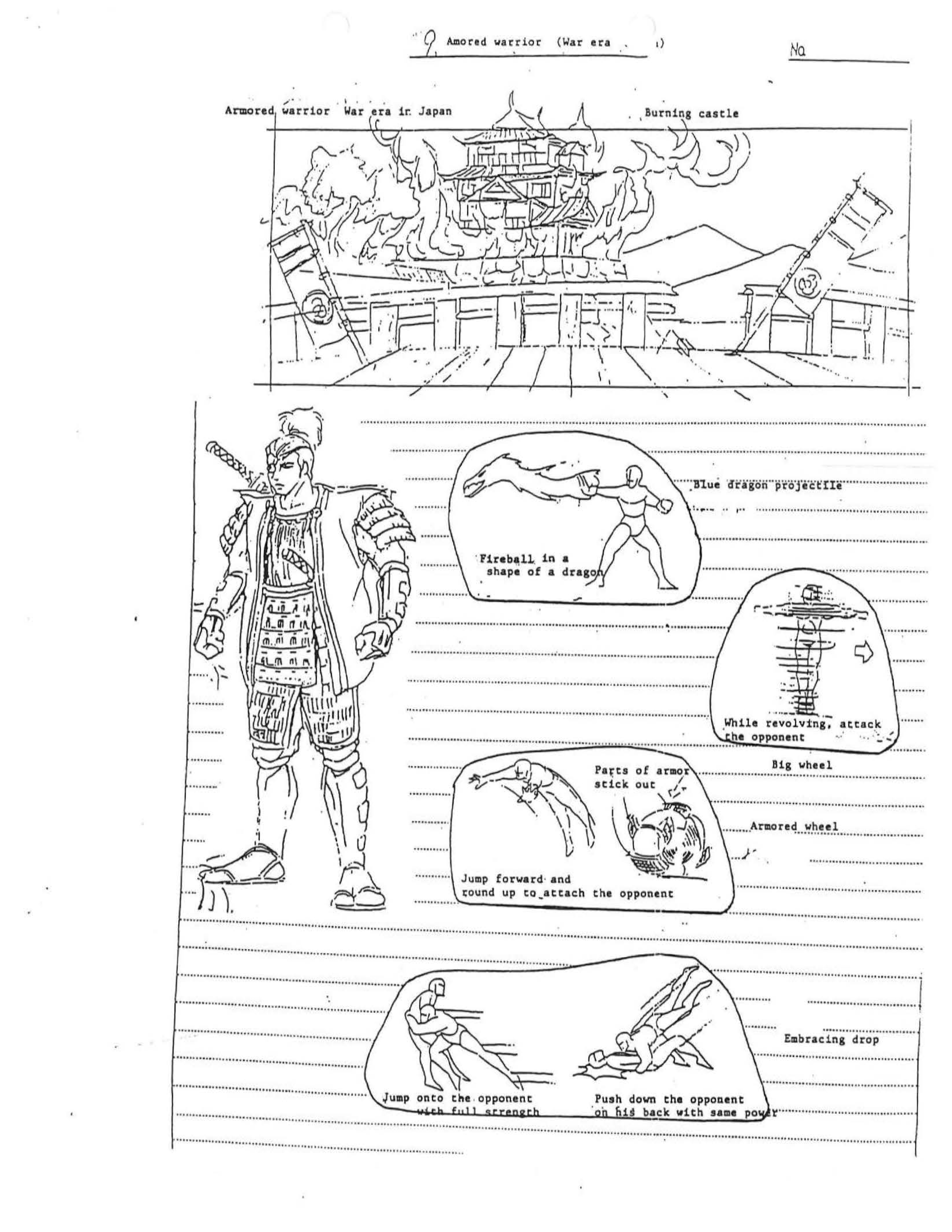

The documents also list fourteen fighters, the last four of which are unplayable bosses. Of the selectable fighters, three are female, which would have been unprecedented at the time. Of the characters listed below, the only ones to be realized in the version of Fighter’s History that eventually hit arcades are Ryoko (“judo girl”), Matlok (“short punk”) and Samchay (“kick boxer”).

Also? It’s very clear that Data East nixed what really sounds like a straight-up rip of Dhalsim, so at the very least there seems to have been some discussion about what they could “borrow” from Street Fighter II and what would feel like too much.

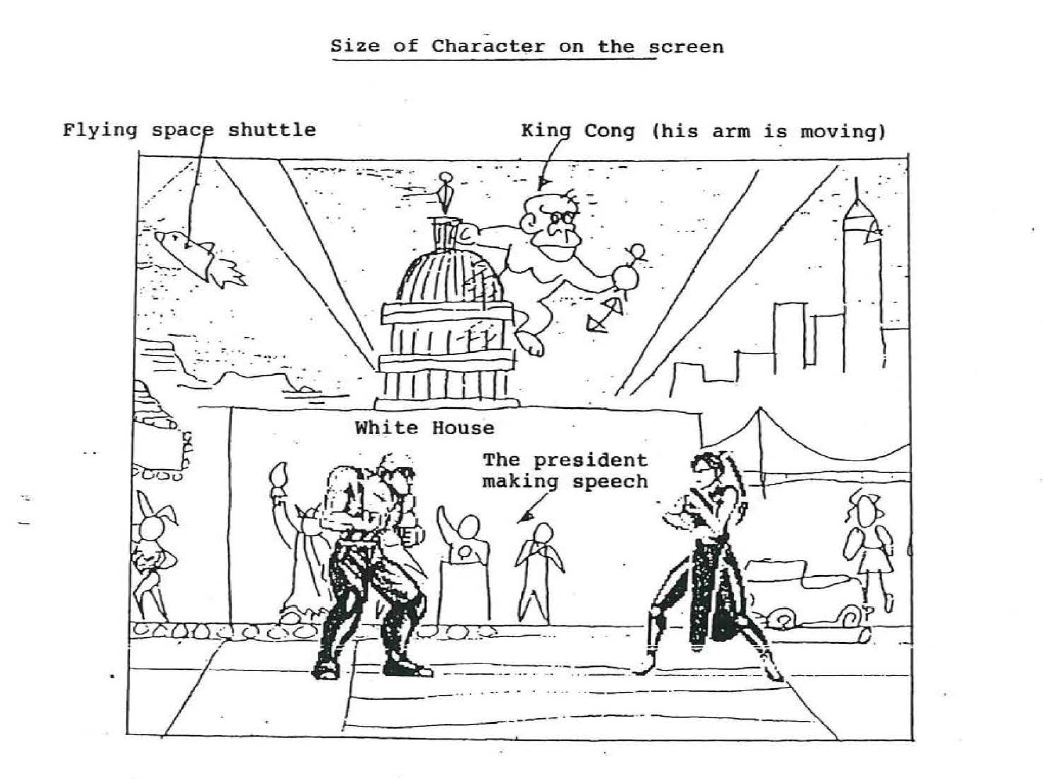

We also see a mockup of how this game will appear in arcades, and I have to admit, I laughed out loud. I do realize this is a rough draft, but I can’t remember the last time I encountered something so crappy.

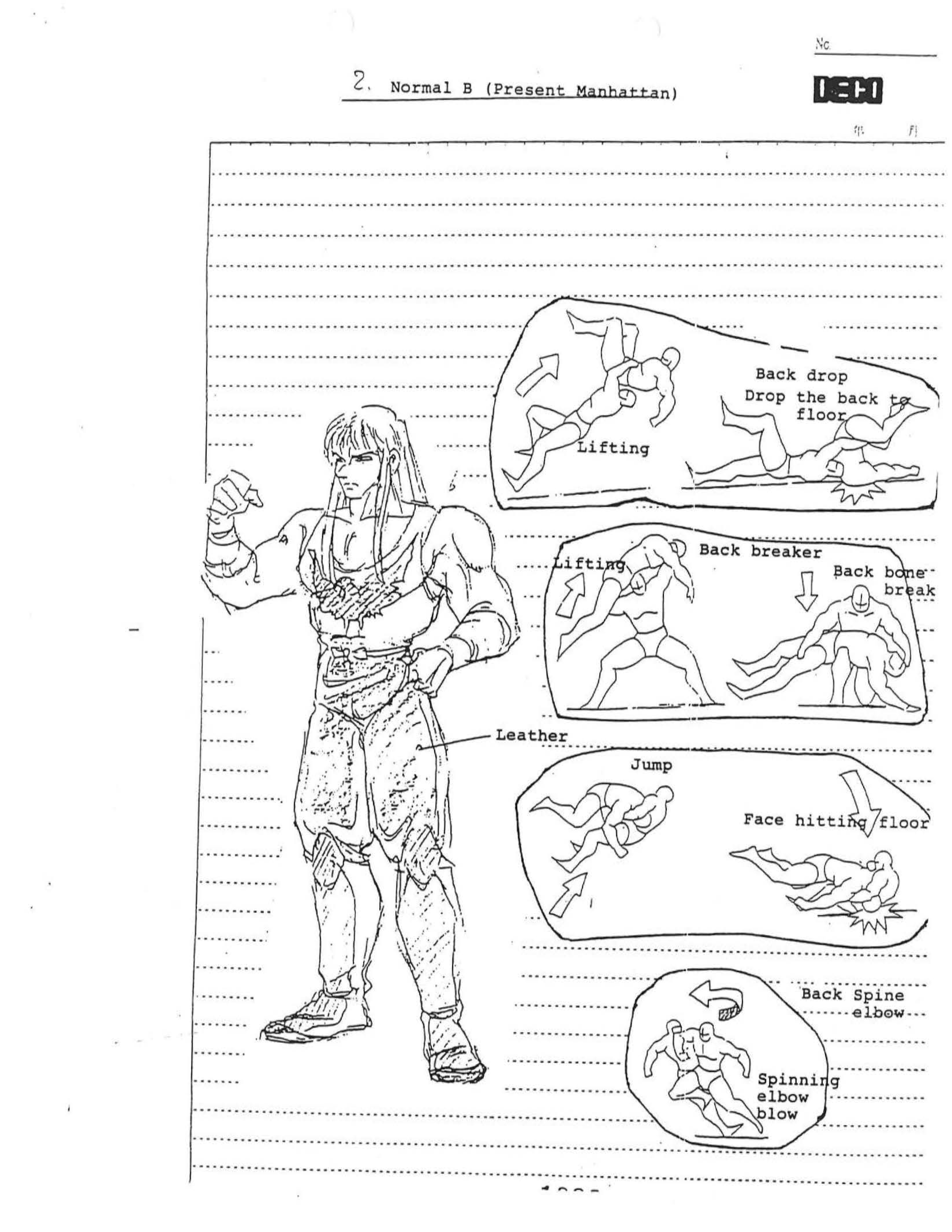

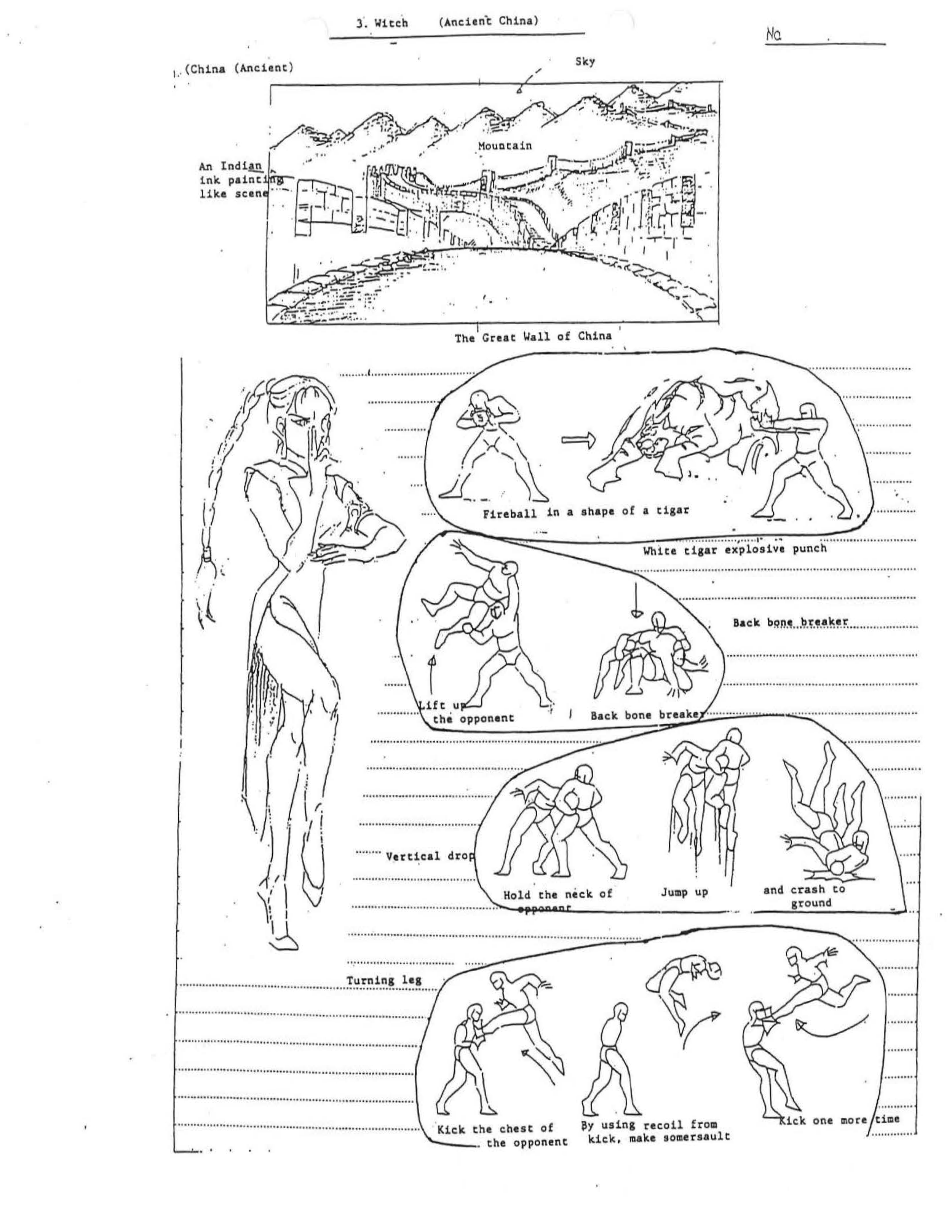

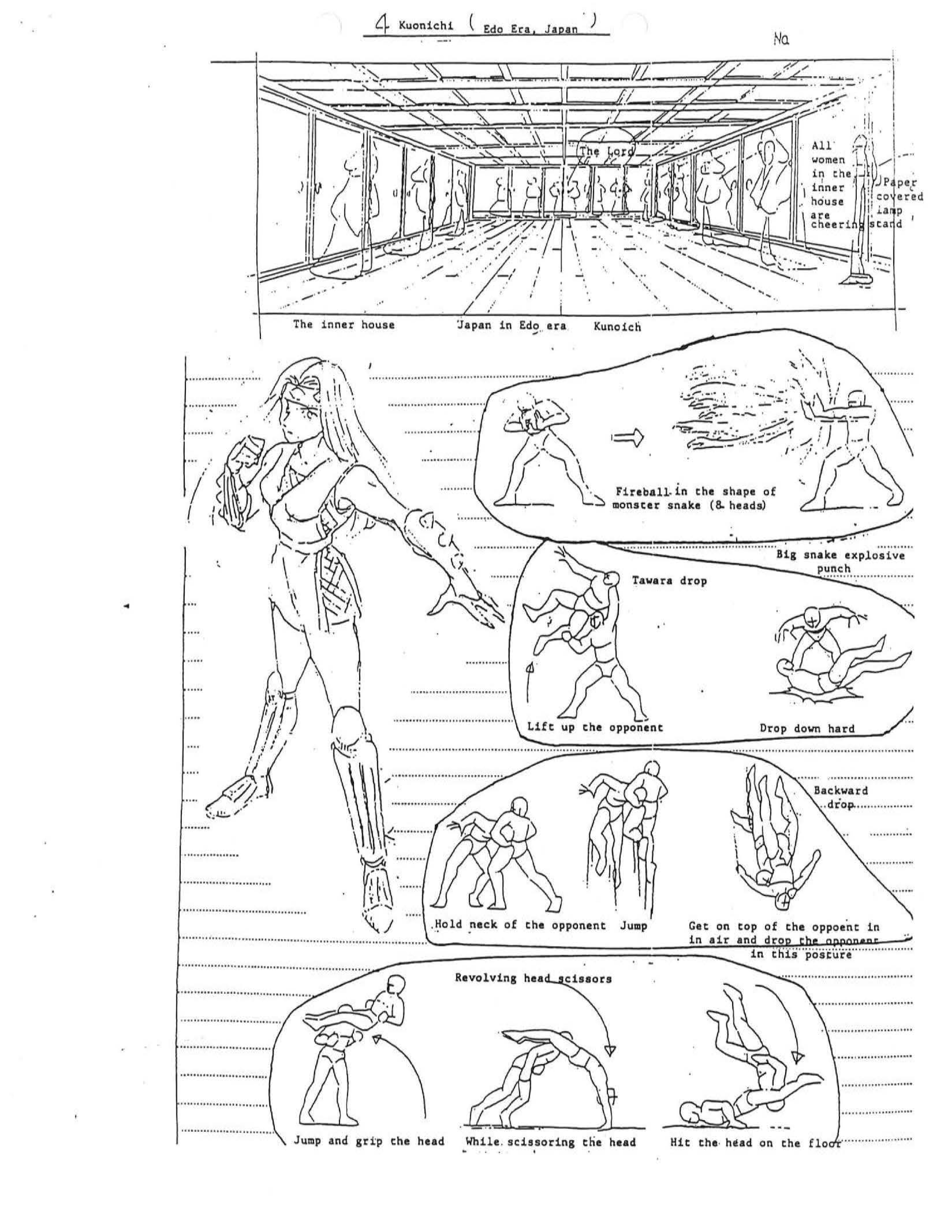

I’m going to conclude with the character pages showing all the Fighter’s History combatants that could have been but ultimately weren’t, and I truly wonder if Data East had made this game if it would have still incurred Capcom’s wrath the way the released version did.

I suppose this guy could have evolved into the Ray character, but with substantial differences. I kind of wish they’d gone ahead with the geography-defying “theme park” version of America depicted in the background, honestly.

It’s interesting that the two lead characters — the Ryu and Ken, basically, are both Americans. There’s no equivalent of this guy in the final version of the game, unless I’m mistaken.

There seems very little witchy about this alleged witch character. It doesn’t seem too much of a stretch that she evolved into Feilin, although this version might have been even closer to Chun-Li, who would eventually get the Great Wall of China as her stage in Street Fighter Alpha.

I’m not sure any version of this female ninja character remains in the final version of the game, though the emphases on leg movies vaguely recalls Yungmie, the “oops, all kicks” character from the sequel.

After World Heroes snaked them with the whole “fighters from different time periods” gimmick, you have to wonder how Data East felt about ADK also getting their own female judoka. The World Heroes version, also named Ryoko, debuted in the sequel, which it arcades mere weeks after Fighter’s History did.

It is interesting and possibly even telling that Matlok was conceived of as a character who would never be mistaken for Guile but then evolved to get closer and closer to him. Had Data East stuck with the original idea, I’m not sure people would have figured him for being a Guile knockoff.

On the flipside, it’s also telling that muay thai fighter Samchay always seemed to have a version of Sagat’s Tiger Knee move.

I guess it’s a novel idea to have a character that has a sword but just doesn’t use it in battle? I suppose it’s possible that Data East just kept sanding off the edges of this samurai-looking guy until they ended up with the game’s “Ryu,” Mizoguchi.

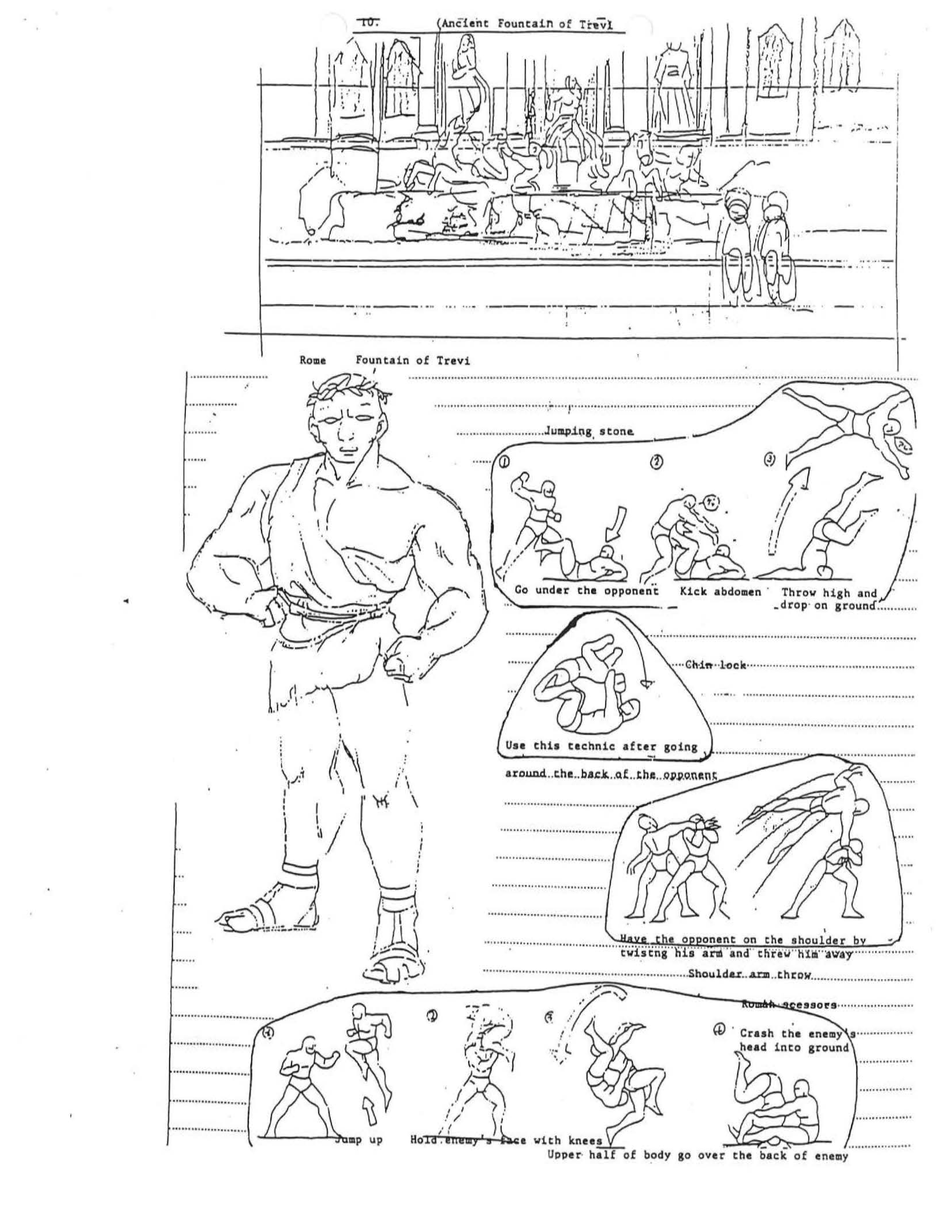

This wrestler character seems further from Zangief in terms of moves. The Trevi Foundtain background still remains in the game as Marstorius’s stage.

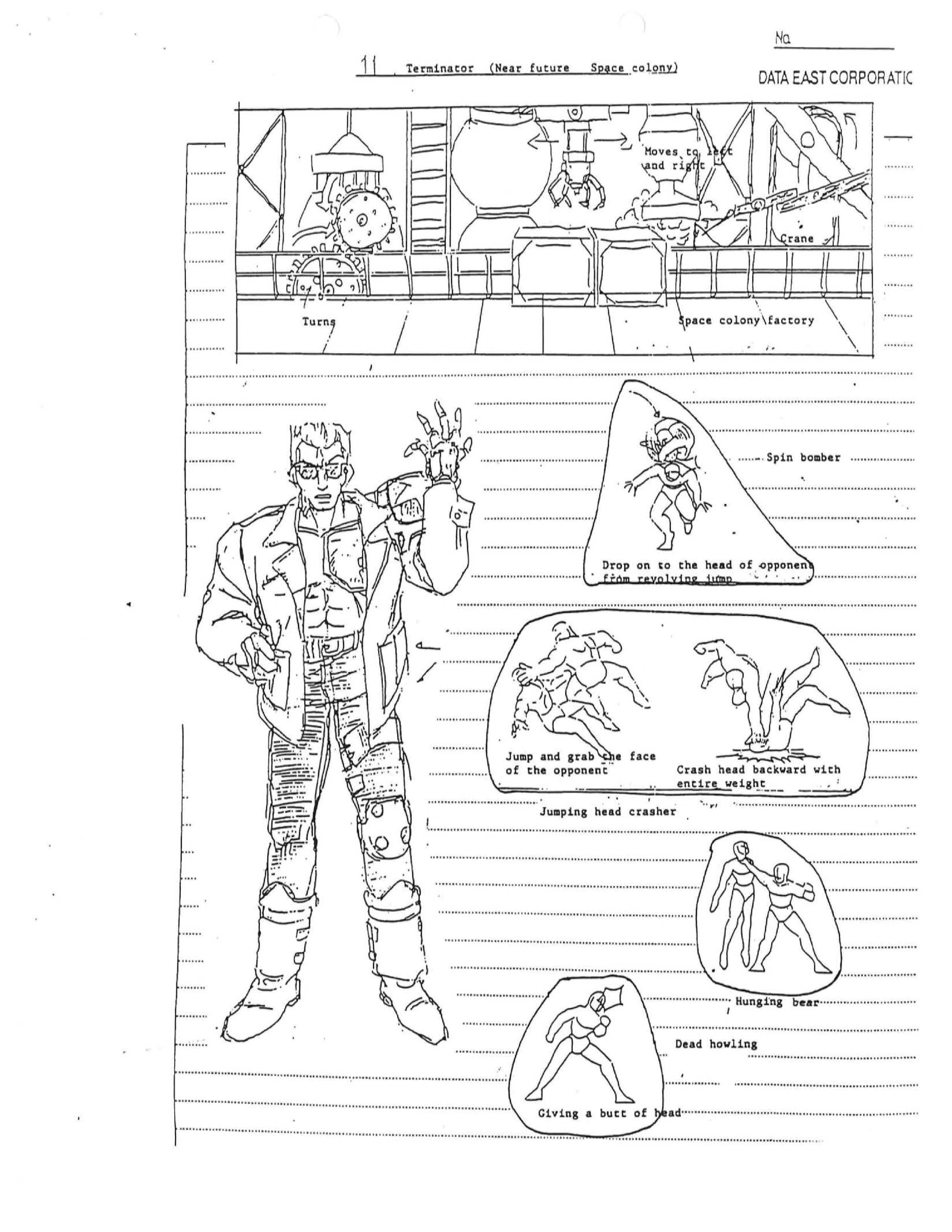

It’s not as if they would have been the first to insert an unlicensed facsimile of an Arnold Schwarzenegger character in a video game… But great word choices here. “Hunging bear.” “Dead howling.” “Giving a butt of head.”

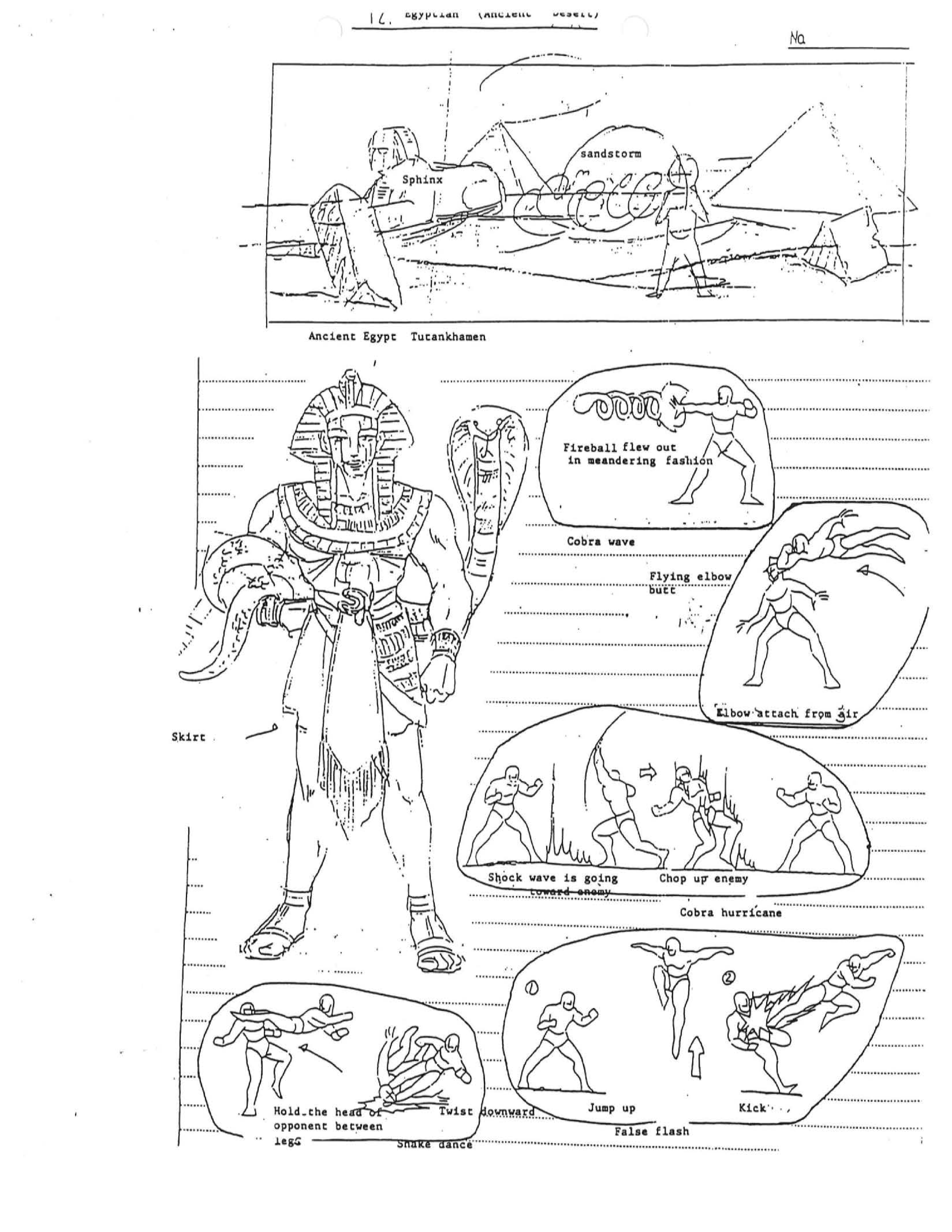

My only note? “Skirt.” Between this guy, Anakaris from Dark Stalkers and Titi/Chaos from Martial Champion, I wonder if there’s ever been a fighting game character from Egypt who wasn’t rocking the trappings of ancient Egypt. Is there?

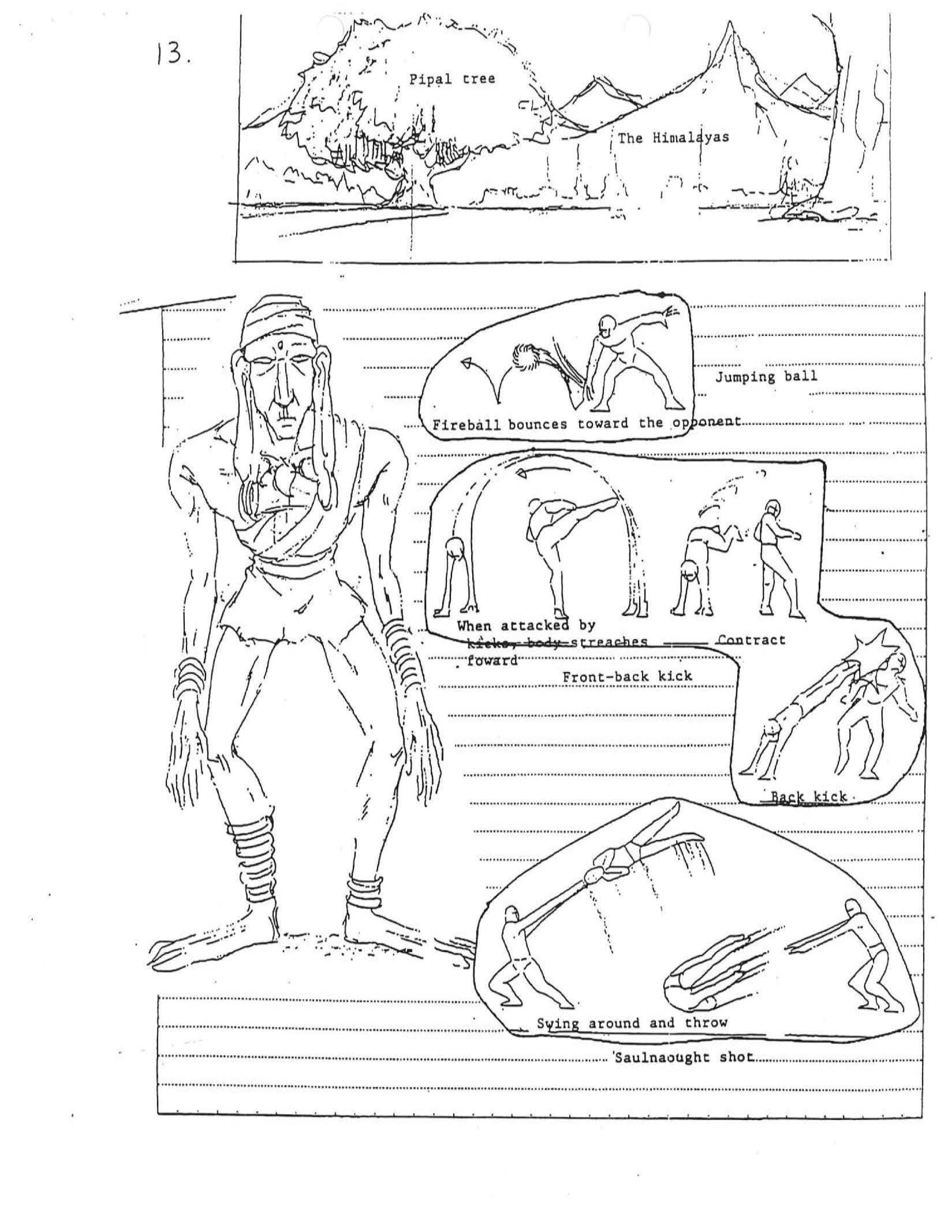

Can anybody explain to me what a “saulnaought shot” is?

Genesis King is represented uniquely with what looks like pixel art. But is it original to this design document? Or is this a character Data East is pulling from another one of its games like it would eventually do with Karnov, the actual final boss? I need to know!

And don’t forget that you can peruse at the same documents I looked at to make this post! They’re all posted over at the Video Game History Foundation, and I’m almost certain there are details I overlooked. Check them out!

.png)