Entactogens like MDMA or mephedrone can be great for emotional work. You can also make them even more effective by leveraging and systematising the intuition that the mind is made of multiple parts.

You know how people sometimes say, “A part of me wants to quit my job, but another part wants to stay”? There are various frameworks that treat this as more than a metaphor — they take it as a more literal description of what’s actually going on in the mind.

This post is a brief introduction to homebrewing your own “parts” framework, plus some thoughts on using it with mind-altering substances. Each of these techniques is powerful on its own, and the flip side of that power is danger: they can stir up old trauma, destabilize you, further “fracture your mind” or otherwise amplify existing issues. The 2-in-1 combination brainhack further increases power and risks — approach it with caution.

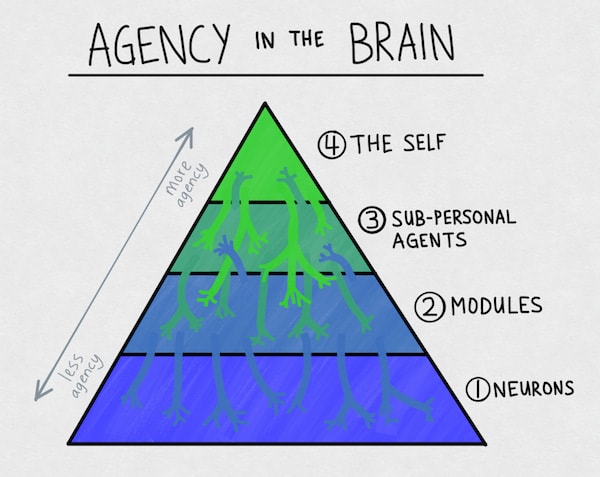

Some “parts” frameworks are neuroscience-based. They start with the “low-level hardware” of the brain.

The above picture is from the article Neurons Gone Wild. It claims that individual neurons are feral: they possess more agency — more capacity to act independently in a goal-oriented-way — than other, more “domesticated” cells in the body.

Neurons form an internal economy in which they compete for resources, forming modules with independent purposes and “jobs.” The modules in turn form sub-personal agents with drives and goals. On the top level you have your ‘conscious self’ with its will — operating over a network of these semi-independent agents.

The brain is an anarchic matrix, particularly hospitable for growing these constellations of agentic structures. We often imagine a unified “I” imposing its will on ourselves and the world, but in practice agency is emergent and bidirectional, if not primarily bottom-up.

Other frameworks start with the “software” of the human psyche and explain the mind in less alien terms.

Internal Family Systems (IFS) is one such framework. It was invented by a family therapist, Richard Schwartz, who was frustrated that his usual techniques didn’t work for some clients. He started paying close attention to how clients described their inner experience. They kept bringing up “parts,” and Schwartz began to seriously entertain the idea that they might be describing the actual underlying reality of the mind being made of sub-parts.

So he started asking the parts questions — and discovered that they functioned like a family. Some parts were hurt, some were protective, some were controlling. Hence the name: Internal Family Systems. Schwarz says that IFS views each person as “ecology of relatively discrete minds”. Note the parallel with the “internal economy” frame from the previous frame.

Mowgli from the Jungle Book was raised by wolves, and I was raised by the internet. My first encounter with IFS was not a therapist’s office, but Twitter and other online resources. The most important one was @Kaj Sotala ‘s Multiagent Models of Mind. Kaj takes apart IFS and rebuilds it from first principles.

One particular consequence of this was not caring much about IFS’s standard classification of parts into “exiles,” “managers,” and “firefighters”:

— exiles are the hurt, vulnerable parts that carry old pain;

— managers are the parts that try to keep life organized and safe so the exiles don’t get triggered;

— firefighters are the emergency responders that jump in with distraction, numbing, or impulsive behavior when the exiles do get activated.

I’ve always found this scheme a bit clunky. In my opinion, it mainly exists to serve the purpose of interfacing with a therapist. But if you’re using this technique for self-therapy, why inherit a “third-person view” of your own mind? You can observe your mind and develop your own classifications, or simply deal with parts on their own terms without forcing them into preconceived notions. That said, your inner system might vibe with it a lot more than mine does.

IFS as a full framework comes with a few more ideas I’m mostly just gesturing at here: a compassionate “Self” that can relate to parts with curiosity and care, the practice of unblending (shifting from “I am this feeling” to “a part of me feels this”), and the principle that there are no bad parts — even the destructive ones are trying to protect something. I found all of these ideas useful. But in this post I’m only borrowing the barebones version: you have parts, you can put attention on them, and you can ask them questions.

The tweet above is by

.

Different parts “grow” at different times in different environments. And the result of this is that we are living in dream mashups of our current situations and old emotional meanings.

One way to test this for yourself is to focus your attention on a part and ask it, “How old are you?” The answer might surprise you. Some of my parts have ages corresponding to key transitions in my life. For example, some of my parts are 17 — the age I moved from Siberia to Moscow to study at university. But sometimes I find parts that are 3 or 4 years old. This doesn’t mean that I literally act like a 3-year-old. It means that a part with that age is blended into my present experience — that’s what a dream mashup is. Parts are like tree rings.

If you interact with parts non-judgmentally, you can often ask them questions and they’ll respond. Aside from “How old are you?”, other useful questions include: “What are your goals?” and “What do you want?” You can enter into an actual dialogue with a part and ask follow-up questions as the conversation unfolds.

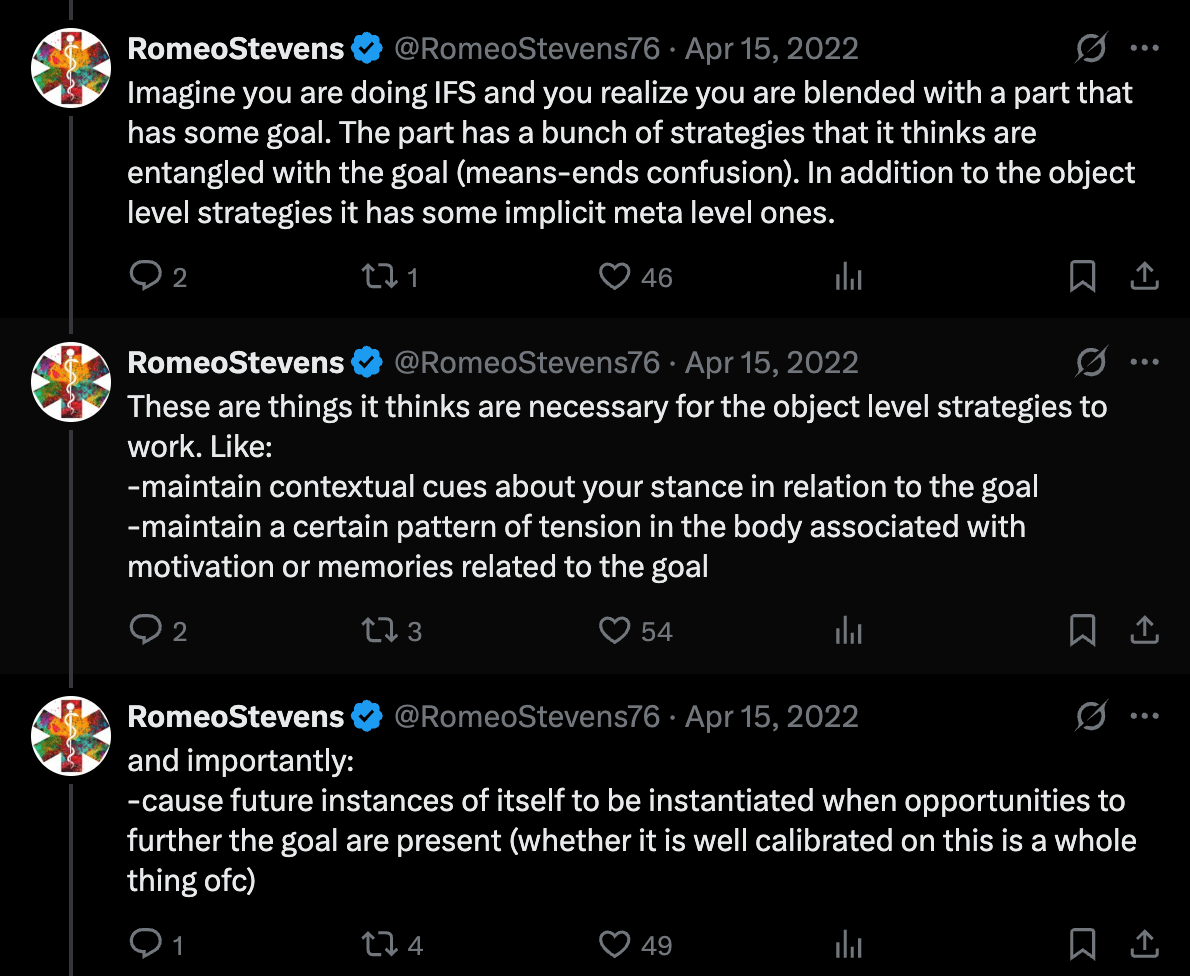

Romeo Stevens has the following take on IFS: sometimes parts are instantiated with the meta-goal of causing future instances of themselves to be instantiated (yes, it’s a loop). I’ve found that it sometimes makes sense to ask a part, “What would it take for you to despawn?” Some parts realize they’re ghosts chasing an incoherent goal and willingly despawn themselves. Others resist despawning — for reasons that might be wise, misguided, or somewhere in between.

I don’t have a fixed set of ready-to-deploy recipes here. Cultivating the culture of one’s mind is more like gardening than precise engineering.

Two years ago I started lifting regularly. People say “listen to your body” when you exercise. A few months ago I realized I can “talk to my body” by directing attention to individual muscles and checking in with each one about how it’s feeling. This is a more bidirectional process than a label “listen to your body might imply”.

Here’s a situation that has happened a few times. I haven’t been to the gym for a week, and I don’t feel like going because I feel “tired.” I check in with each individual muscle and discover that all of them are craving exercise — the “tired” feeling isn’t being generated by the body at all. It’s an idea stuck in my mind. That idea is inaccurate, and the parts framework helps the evidence from the body — which wants to move — propagate through the system. Then I go to the gym excited for it.

Another situation: sometimes I do deadlifts, like in the picture. They’re quite strenuous for the lower back — those muscles are among the primary lifters. So I check in with them: “Are you doing alright? Can you do one more set?” Sometimes the answer is “Hell yes,” sometimes “No more than one more set,” and sometimes “No, I’d rather not.” All of this happens on a linguistic level — I literally have these words pop up in my mind.

I have no idea if other people talk to their backs this way. What do people even mean when they say they “listen to their body”? Not in the loose sense of “pay attention,” but in the precise sense of what mental motions and attentional patterns they’re actually executing?

People’s cultures of mind are wildly different. You might also find unusual ways to repurpose and reuse your own “parts” framework.

I recommend practicing an IFS-like framework sober first, perhaps mixing it with meditation. Get a feel for which parts tend to come up, what it’s like to ask them questions, and how often parts present as coherent subagents versus a soup of emotional reactions. Build a set of tacit skills for dealing with inner multiplicity.

Entactogens like MDMA and mephedrone can make the mind more plastic and more comfortable with negative emotions such as cringe, shame, and guilt. They often create a temporary sense of emotional safety and compassion: things that normally feel unbearable become painless or painful-but-workable. In that state, the grip of the top-level, self-like agent on the underlying network of subagents loosens, while much of the lower-level dynamics stay intact. This can be useful for helping parts despawn and for getting clearer, more honest answers when you talk to them.

Psychedelics can also be useful. Sometimes I can literally feel subagents renegotiating a new equilibrium. One time, on a very intense LSD trip, I felt nicotine-assisted gym-going subagents renegotiate their structure with the rest of the mind via a self-unifying wave.

However, most of the time — at least for me — psychedelics cause too much disintegration. The mind is a Darwinian meaning-making machine, and psychedelics ramp up the Darwinism factor by 100×. My IFS-like parts framework itself starts to disintegrate as well.

Psychedelics allow the mind to roll out much bigger updates; entactogens often hit a sweet spot between plasticity and coherence, allowing for smaller, targeted updates in a more comfortable way.

If psychedelics are like detonating a meaning-bomb in your mind and watching the pieces reconfigure, entactogens are more like temporarily turning gravity down so you can gently rearrange furniture while the house stays mostly intact.

I’ve been experimenting with these techniques on and off for several years now. And I still feel like I’m only seeing one little corner of the space. Other minds will have different default settings, different parts cultures, different failure modes.

If you try any of this, treat it as a set of suggestions, not a template. Keep what clicks with your own inner ecology and throw out the rest. If you run into significant issues, consider talking to a licensed therapist.

This post is, to some degree, a response to this comment by

: “Can you do a deep dive on the emotional/trauma resolution effects of this or other psychotechnologies that worked well?”. I’d love to hear which pieces were most useful or confusing, and what you’d like a follow-up to dig into.

- : Multiagent Models of Mind, the sequence of articles that kickstarted my understanding of IFS

- : My current take on Internal Family Systems “parts”

- : Different configurations of mind

- : Good introductions to Internal Family Systems

- : Mental Mountains

- : Dream Mashups and this twitter thread on them

- : Gendlin’s Focusing, another technique that’s more low-level, but useful in parts work

.png)