If you wanted to construct a scenario that was damaging to American claims to economic leadership in the world, it would look like the Trump administration.

It reinforces the long-standing sense that the position of the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency and leading currency of international trade is anachronistic and out of kilter with America’s diminishing significance in the world economy.

At least since the 1970s this has been inspiring talk of an imminent end of American financial hegemony. Half a century of speculation about America’s future as an economic leader has given rise to a species of historico-economic futurism I’ve labeled fin-fi(ction).

Talk of the end of dollar hegemony has remained speculative because though it seems foreordained that the dollar “must fall”, the countervailing forces are, in fact, powerful.

Principal amongst these countervailing forces are network effects that make the dollar more fungible and useful than any other international currency. Neither the Euro nor the RMB have the dollar’s widespread acceptance, or the openness, depth and sophistication of US financial markets.

Network effects are key to the fungibility and widespread use of any currency, whether domestic or international and they are key to explaining the dollar’s resilience. They are, what you might describe as “flow factors” i.e. forces that are continuously produced and reproduced. Every time a barrel of oil changes hands for dollars, every time a new loan is issued in dollars, every time a dollar derivative trades, the forces upholding dollar hegemony are reinforced.

In addition to these “flow factors”, what we should not underestimate are what might be called “stock effects”. This was brought home to me in a fascinating conversation with Eswar Prasad - of Dollar Trap fame - at Summer Davos in Tianjin. In a chance encounter in the downstairs lobby we fell quickly into talking about the future of the US currency - a hot topic at the meeting. And Eswar hit me hard with a data point that doesn’t come up enough in conversations that tend to be dominated by the question of America’s share in global reserves: America’s net international investment position.

In the first quarter of 2025, according to data recently released by US BEA, America’s net international investment position currently stands at negative $24.61 trillion i.e. US liabilities to foreigners exceed US claims on the rest of the world to the tune of 90 percent of US GDP.

Prasad’s basic point, first articulated in his “dollar trap”, is that the US has the rest of the world on the hook. If the dollar depreciates that makes American exports and newly purchased assets cheaper to buy, but on net it is America’s existing investors who suffer the loss. Or, to put the same point the other way around, there is a mighty coalition of foreign investors who have an interest in upholding dollar strength, to the tune of $24.61 trillion.

Superficially this might sound like a restatement of the familiar “exorbitant privilege”. America’s negative net position is hardly surprising given its ability to finance trade deficits year in year out by dollar-denominated borrowing from the rest of the world.

But a simple explanation in those terms is belied by the chronology of the imbalance. Though America has a long-standing tendency to accumulate liabilities to the rest of the world, it is since the 2010s that the net foreign asset position has lurched massively into the negative. Though the US has run huge current trade deficits in this period, the net foreign asset position has deteriorated by far more than one would expect on that basis.

Source: NBER

Whereas the current account deficit actually tightened in the 2010s, the net asset position slid into negative as never before.

Source: Atkeson et al

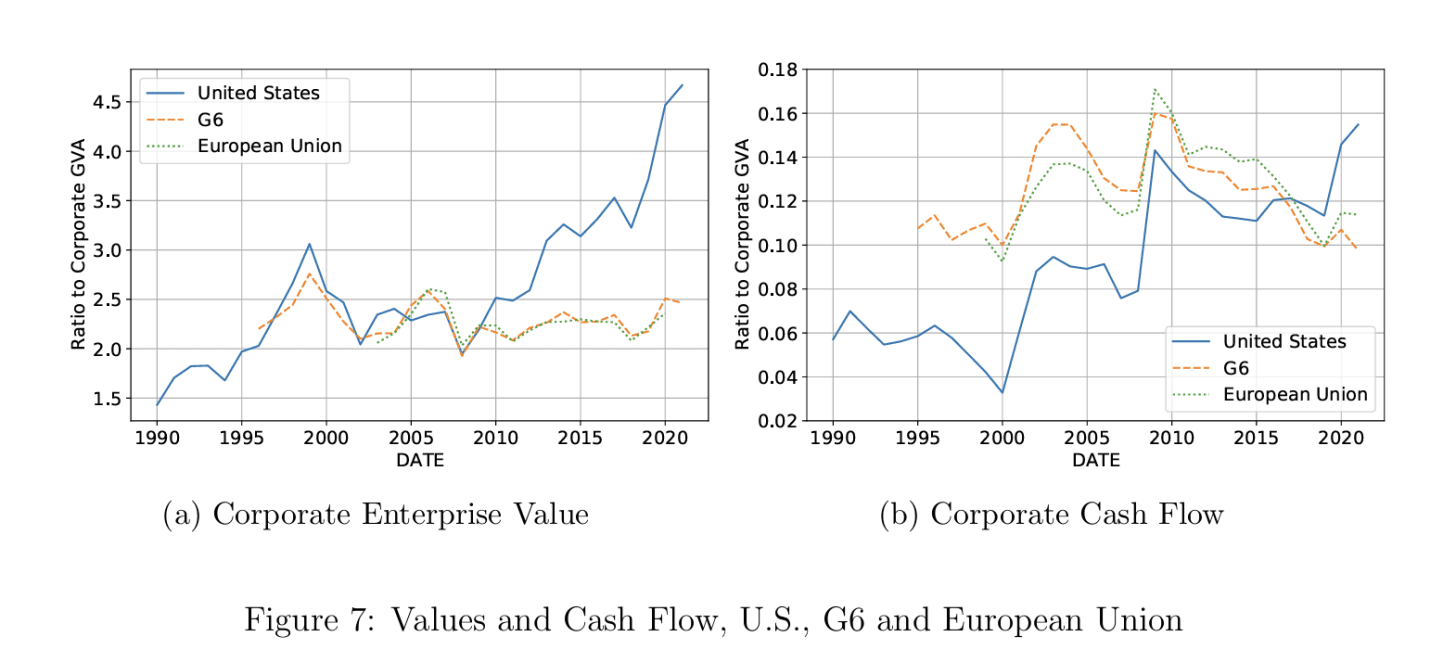

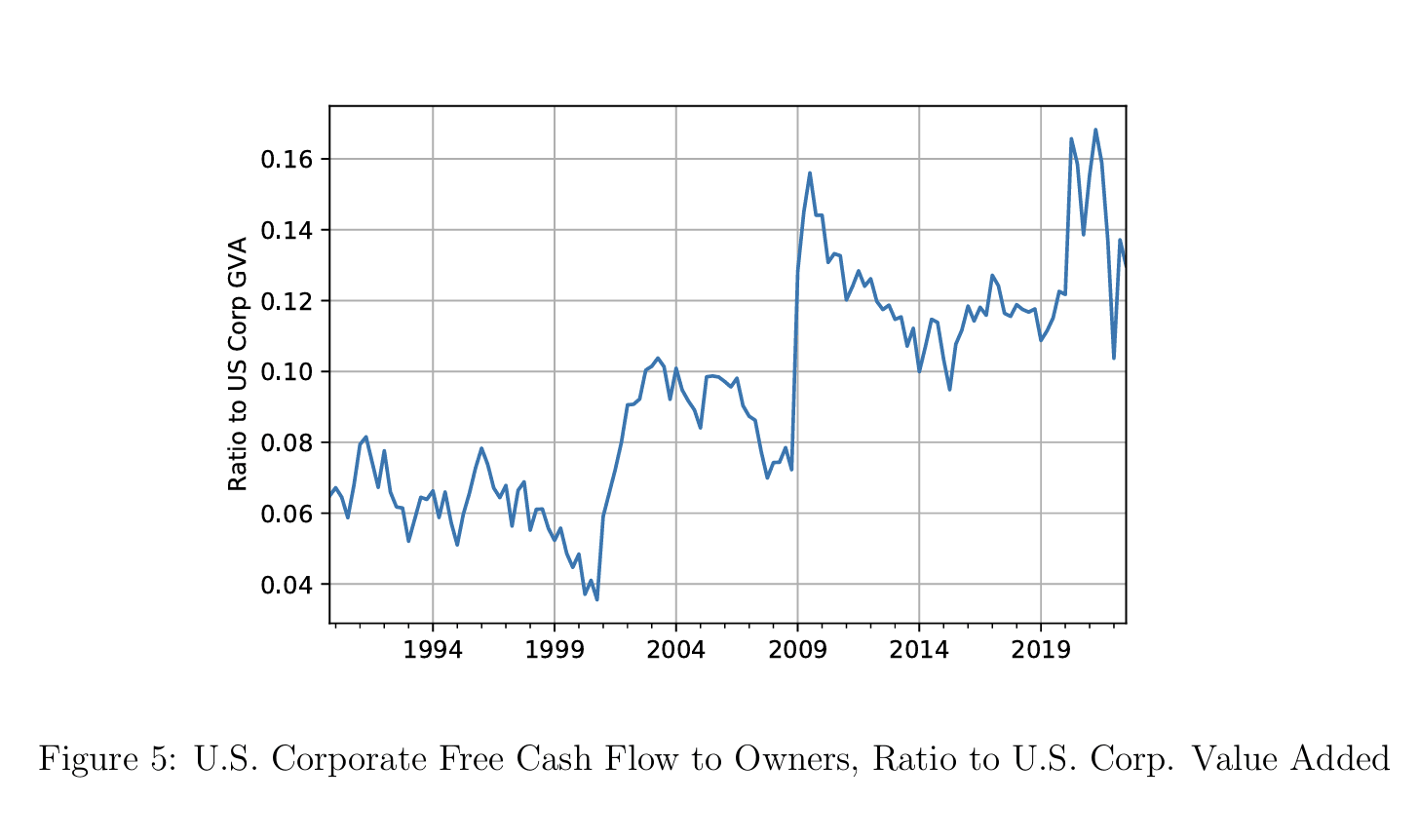

Detailed research on the causation and consequences of the imbalance by Andrew Atkeson, Jonathan Heathcote, and Fabrizio Perri suggests a story of three phrases:

In the first (phase), from 1992 to 2002, the US Net Foreign Asset (NFA) position deteriorated from minus 5 to minus 18 percent of GDP, paralleling rising deficits in the current account. During the second phase, from 2002 to 2010, the NFA position was roughly stable while the current account continued its negative trend. This was the era of America’s special privilege, as previous researchers dubbed it, because it appeared that the US could finance its trade deficits with the high returns earned on foreign assets. That privilege came to an end in the third phase, 2010–21, when the NFA position fell by more than 40 percent even though the current account (deficit, AT) as a percentage of GDP was roughly stable. By 2021, the decline in the US NFA position had not only negated the phase of special privilege, but had fallen to a lower level than would be indicated by the cumulated current account deficits over the full period from 1992–2021.

The reason for the plunge during the third phase was a boom in US stock prices that was not matched elsewhere.

While Americans were earning moderate returns on their foreign stocks and other financial investments, foreigners were earning very high returns on their US holdings.

The researchers consider two possible explanations for the stronger returns on US stocks than their global counterparts during the last decade. One is that US firms made substantial investments in productive capital that are not measured in the national accounts, while the other is that they experienced a rise in market power and a corresponding increase in monopoly profits. If the first explanation was correct, the US would have experienced a period of low or negative measured output and a huge trade and current account deficit, far beyond the deficit actually reported. The researchers conclude that since this was not observed, unmeasured investments may have contributed to the decline of the NFA position, but they are unlikely to be a dominant factor. A rise in monopoly profits and a larger share of value added accruing to the owners of firms, however, appears much more consistent with the NFA movement and other macroeconomic data. Since foreign investors own roughly 30 percent of the US corporate sector, their share of the increased profitability of this sector corresponds to an annual flow of about 1.3 percent of US GDP.

This succinct and powerful analysis adds a key element of political economy that is often missing from arguments over the dollar system, all too often phrased in national terms. We talk as though the rest of the world as a collectivity suffers the unequal terms of trade implied by America’s exorbitant privilege. It is often said that the “safe asset” status of US Treasuries is ultimately grounded in America’s national military power. Both claims have an element of truth to them. But as Atkeson et al remind us, global investors flock to the United States not simply because the United States supplies protection, or serves as a unique issuer of “safe assets”, but because investing in America offers outsized returns thanks to the country’s lop-sided domestic political economy. America is a great place for corporates to make profit and that is ultimately what attracts investors and accounts for a large part of America’s net foreign liabilities. Managers of foreign capital enthusiastically buy into the American profits bonanza.

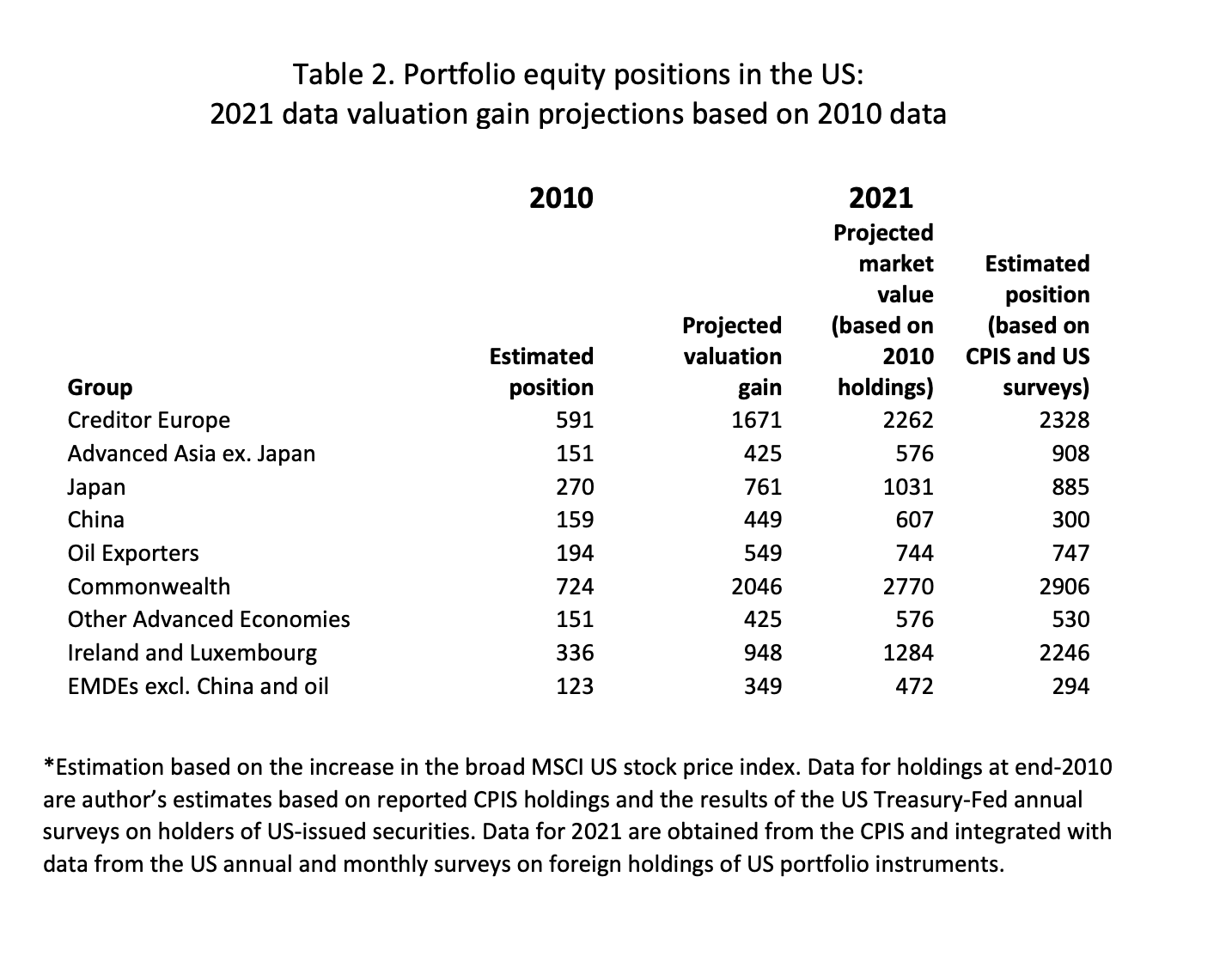

And who is it that has availed themselves most actively of this opportunity since America’s net asset position slid dramatically into deficit?

One story familiar from the 2000s is that America’s lop-sided political economy is the counterpart to the unbalanced class politics of export-surplus economies, notably China. Klein and Pettis argue that the first China shock of the 2000s, with a huge surge in Chinese exports, was a form of “class war”.

Theirs is a story centered on the interaction between capital flows, exchange rate and the manufacturing trade balance, not the net international investment position, which was propped up in the 2000s by high returns from US investments abroad. Since the 2010s that balance has broken down. As far as equity markets are concerned, the world entered a stage of “American exceptionalism”. Who were the principal foreign beneficiaries of this lop-sided era of American growth?

To answer this question we can draw on the work of Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, formerly of the IMF. In his paper “Many Creditors, One Large Debtor” Milesi-Ferretti breaks down the surge in America’s foreign liabilities by foreign investor. Though there are a mass of technical issues in constructing consistent capital account and financial balance sheet data, he is able to reach some clear conclusion:

On the creditor side the main counterparts (to the US build-up of liabilities) have been advanced European and Asian countries, where net asset accumulation has been driven to a large extent by large current account surpluses. Valuation gains on holdings in the United States have accrued mostly to countries with large equity and FDI positions in the US, including most Anglo-Saxon countries (for instance Canada) as well as countries with large sovereign wealth funds, including Norway and a number of oil exporters in the Middle East. The creditor position of China has instead declined both as a share of domestic and global GDP, as its current account surplus has shrunk and its currency has appreciated substantially … Our analysis of financial balance sheets indicates that rising creditor positions are positively associated with the net financial position of the government, the net financial position of nonfinancial firms (in turn related to stock price valuations and the location of firms’ nonfinancial capital), and the size of the balance sheet of institutional investors such as insurance companies and pension funds. The latter can contribute to a stronger net external position through higher saving or a greater propensity to invest in equity instruments overseas. Among advanced European and Asian economies countries such as Norway and Singapore provide the most vivid illustration of the link between the net external position and net assets of the government, but the relation holds more generally. The empirical analysis also shows how these factors cannot account for the very large creditor position of Taiwan, likely associated with geopolitical factors.

In other words the principal beneficiaries of the outsized returns in the US economy were other advanced economies and members of America’s global hegemonic coalition. This is significant because it shifts the terms of the original “dollar trap” discussion.

The huge reserve build-up in emerging markets and above all in China in the 2000s and early 2010s aligned the question of the future of the global dollar system with the challenge of “the rise of China”. This was both a geopolitical issue and because it reorientated trade around the gradient between advanced and emerging economies, it raised questions about inequality and the social order in the West. The dollar system appeared as a trap from which no one could exit as much as they might want to. The larger their surpluses, the larger their claims on the United States, the deeper the trap became.

The finding by Atkeson et al would seem, at first glance, to reinforce and extend the “class war” diagnosis of the dollar system in the 2000s. In the 2010s global investors made outsized gains from America’s profit-driven stock market boom. But if we accept Atkeson et al’s three-phased chronology and combine it with Milesi-Ferretti’s analysis of America’s creditors, we see the stark difference between the 2000s and the 2010s. The 2000s really were a phase of the opening up of a new global economy. The principal dynamic was in emerging market growth and expanding US current account deficits. The 2010s, by contrast, saw a stagnation and then retreat of Chimerica. Instead the “new creditors” consisted mainly of core members of America’s hegemonic bloc. Their financial claims were safely and comfortably accommodated in America’s booming financial markets. To speak of a dollar trap flatters them. To be trapped you have to have some impulse towards escape. That might be fairly said of the rising emerging markets of the 2000s, notably China. But hardly of the “new creditors: of the 2010s. Their experience was something closer to that of a gilded cage. To use the language of the Cold War historiography, if this is empire, it is empire by invitation.

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I hope you find that it offers valuable insights, interest and provocation. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

.png)