This essay first appeared in my newsletter. Sign up here if interested in Unf^cking Education.

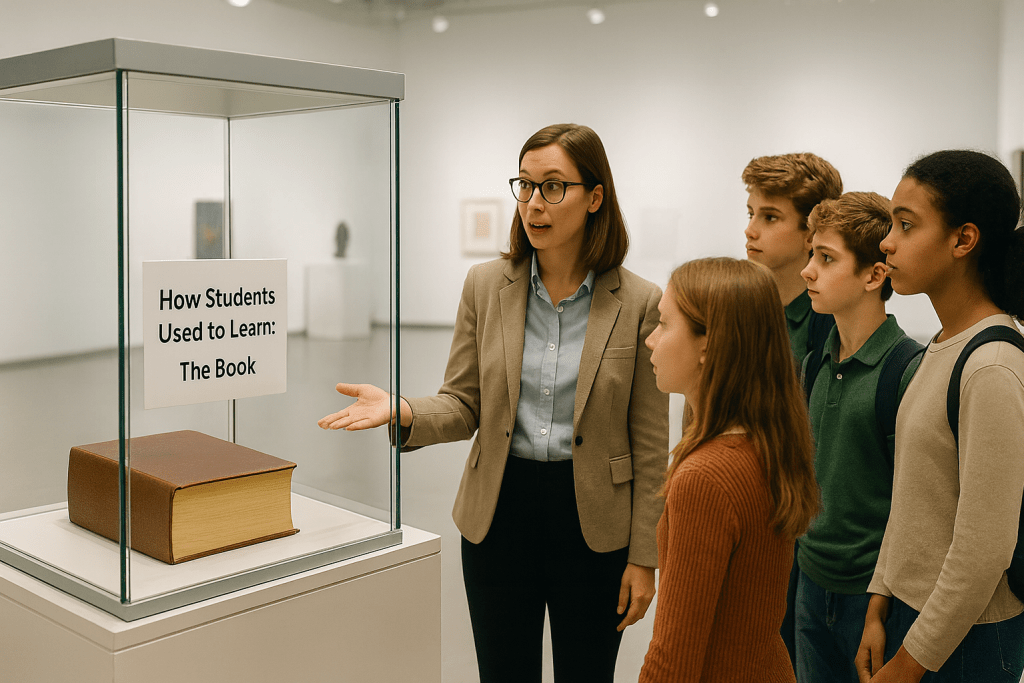

Recently, adults have been sounding the alarm that students are not reading books.

The underlying worry-infused premise is this:

- Our students are not reading long-form texts

- Civilization will collapse if we do not fix it.

As a result, the discussion centers on how we get back to past days of reading glory.

That is the wrong frame.

As it relates to reading, the toothpaste is out of the tube.

Translation: We are not going back to a time when students sat quietly and brute forced (or more likely used Cliffs Notes or SparkNotes) to work their way through The Odyssey or Hamlet.

There are too many competing distractions, and alternative media formats like video, audio, memes, graphics and emerging interactive formats that are not just more compelling but which may also offer the benefits of speed, lower cost and ease of creation.

While the old guard view this as symptomatic of decline and pine for the “good ol’ days”, we should look at this as an opportunity for transformation.

Instead of trying to reverse the tide, schools and educators must first have to admit the obvious.

We live in a post text world.

One of the most clear-eyed views of this recently came from an unexpected source.

Princeton University history professor D. Graham Burnett describes it well in this clip (from his appearance on the Hard Fork podcast hosted by Casey Newton and Kevin Roose).

It will pain me to say this but long-form immersive literacy is coming to an end as a widespread cultural phenomenon.

He views this as a positive and goes onto explain what new literacy looks like in the future.

He sees a post text world for universities. This same phenomenon will play out in middle school and high school as well (but obviously with development-appropriate adjustments).

This is Not the End of Literacy, But the Expansion of It

When some people hear, post text, their mind goes to illiteracy.

That is wrong.

This just means literacy has multiplied.

A hundred or even fifty years ago, being literate meant you could read and write.

Today it means you can tell stories through text, video, audio, images, and even code.

That is not decline.

That is expansion.

The skills students practice when they produce a podcast or a short video public health campaign directly tie into the ways we increasingly use to persuade, explain, and collaborate.

The Reading Decline Is Real

This reading decline is not being imagined.

- Professors at Columbia, Georgetown, and Stanford report that many students arrive on campus having never read a full book. One Columbia professor said he was “bewildered” when a student admitted she had never been required to finish one. “My jaw dropped.” (source: NY Post)

- In 1976, only 11.5% of high school seniors reported reading no books in the previous year. By 2022, that number was 40%. At the University of Pittsburgh, only 17% of students reported always reading their assigned books. (source: Pitt News)

- Pew Research shows 9-, 13- and 17-year olds all seeing less frequent readers as well as increases in those that read rarely.

image

imageThe decline is real.

I also don’t want to imply that it is non-impactful.

This decline affects cognitive development. Reading, in fact, is a better predictor of academic success than family income or parents’ education.

For a deeper look at why reading still matters and what the research says about how to get students reading again, see my essay Why The Kids Hate Reading, and How We Can Fix It.

What We Might Actually Lose

Deep reading develops unique cognitive muscles:

- the ability to sustain attention through a 300-page argument

- to hold complex ideas in tension

- to follow an author’s reasoning across chapters

These capacities build patience with complexity and comfort with sustained intellectual effort.

We may genuinely lose some of these capabilities as we shift toward this more multimodal literacy.

But the choice is not between preserving these skills and developing new ones.

It is between clinging to one already declining medium while students fall behind in all the others. The pragmatic thing to do is accepting some loss while building the capabilities that match how they will need to communicate.

The Path Forward: Choice and Agency

There is a way to keep deep reading alive without coercing students and making it compulsory.

The research is clear: when students have choice in what they read, their motivation and volume increase.

A University of Houston study found that students self-reported significantly higher motivated reading behaviors when provided with choice of books compared to teacher-assigned novels. When eighth graders shifted from assigned reading to choice reading, researchers documented “increased reading volume, a reduction in students failing the state test, and changes in students’ reading behaviors” (Allred, 2020).

Other studies, such as Pak and Weseley (2012), show how mandatory tools like reading logs can actually decrease motivation, while voluntary approaches preserve it.

I have written at length about the power of choice, relevance, and intrinsic motivation in Why The Kids Hate Reading, and How We Can Fix It. That essay lays out the full case for why agency is the oxygen of reading. The short version here: autonomy matters, and without it, long-form reading will continue to die.

Why Schools Should Not Fight This

This brings us to the bigger mistake: schools are still fighting to restore an old order instead of preparing students for the new one.

When schools focus on “getting kids to read again,” they are fighting the last war. More often that not, they’re also fighting with yesterday’s weapons: shame, punishment, coercion and other trinkets of subordination (incentives to drive reading don’t work).

None of these work.

It is these same weapons they’re employing in the battle with AI which they will lose all while they break education completely.

They are pouring energy into defending one medium while missing the larger goal, which is clear thinking across many mediums.

The irony here is that teaching video and audio can strengthen text literacy.

- Podcasts begin with scripts

- Videos start with outlines or storyboards

A student who learns to cut down a script for a three-minute video is practicing concision and narrative structure. (See also: Why Your Kid’s YouTube Dreams are Smarter Than You Think)

These are the same muscles that make a better writer.

What This Looks Like in Practice

At The School of Entrepreneuring, we are building for a post text world and designing structures that expand literacy instead of narrowing it.

This goes beyond curriculum units to how the entire school experience and environment is shaped.

Individualized Reading Journeys

Every student works with their coach to develop a customized reading plan. Instead of marching through the same assigned novels, they select books that align with their interests, goals and proficiency.

Coaches meet with students 1:1 to set goals, discuss & reflect on reading and stretch them into new genres and levels of complexity. Research confirms that student choice significantly increases reading motivation and volume (Allred, 2020; Guthrie & Humenick, 2004).

Communities of Readers

We also look to make reading social rather than solitary. Book clubs are formed around shared interests, not teacher mandates. Students recommend texts to one another, debate ideas, and build what researchers call “communities of readers” (Daniels, 2002). This approach transforms reading into a collective pursuit, which has been shown to increase both comprehension and engagement.

Dedicated Deep Reading Blocks

The schedule includes time for sustained, distraction-free reading. Students choose what they read during these blocks, but the time is protected. Research shows reading stamina when practiced intentionally (Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997).

Challenge-Based Learning

At the School of Entrepreneuring, students do not just attend rigid subject-based classes but instead work on multidisciplinary Challenges. These multi-week challenges are where students research, create, and present solutions across formats.

The Challenge design is rooted in research showing that agency and authentic impact are essential drivers of adolescent motivation (Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Challenges might include:

- Fight a Disease, Change the Narrative: Research a disease of personal interest and design a campaign that spans a podcast, a children’s book, a short documentary, and an advocacy memo to legislators.

- Fix What’s Broken in Your Neighborhood: Identify a pressing local issue, interview local residents, and create a persuasion campaign that could include a short narrative video, flyers, social posts, and a presentation for the town council.

- Save a Local Small Business: Partner with a neighborhood business to drive awareness, using memes, short-form videos, and digital ads.

These challenges ensure students still engage deeply with ideas and research, but in ways that feel alive, consequential, and connected to the world beyond school (Montessori, 1949; Damon, 2009).

.

The Opportunity

For the first time, students can practice the full spectrum of communication, not just one.

They can argue in an essay, persuade in a video, inspire in a speech, and distill in a chart.

The students who thrive will not be the ones who mastered a single medium.

They will be the ones who move fluidly across them all, carrying their ideas with clarity no matter the format.

Seen in this light, post text is not the death of literacy.

It is the largest expansion of literacy in human history.

Schools face a choice.

They can cling to nostalgia and graduate students who are even more disengaged and unprepared.

Or they can embrace multimodal literacy and graduate students fluent in the communication media of today and the future.

.png)

![Is AI a Bubble? [Exponential View]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Q451!,w_1200,h_600,c_fill,f_jpg,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9e8f5115-72c4-4bdf-9aa1-62cb9d44a09e_1024x1024.png)