A primary function of government is to ensure that economic success among companies is tied to creating real value for others. But today, many of the most profitable products on our phones no longer focus on providing value—instead, they aim to consume our time. In a recent trial, Mark Zuckerberg testified that just 20% of the content consumed on Facebook and 10% of the content consumed on Instagram is from friends. The original mission to “connect people” has been replaced. “The vast majority of the experience,” he admitted, “is more around exploring your interests, entertainment…” But under this vague notion of ‘interests’ and ‘entertainment’, nearly anything can be justified, including products that keep many kids attention “almost constantly.” It can justify children watching strangers fight each other, viewing sexually suggestive dances, or forming romantic relationships with AI chatbots. What matters is not whether the content is perceived to be valuable or meaningful. Instead, what matters is only that it keeps people, especially kids, interested and engaged. And for many companies, giving people more of what they “want” just happens to align perfectly with their bottom line.

But being “entertained” by our phones isn’t necessarily what people truly want, at least not in the considered, aspirational sense. Ask the people around you—kids or adults—and you’ll find that many people want to spend less time on their phone. In a recent poll, 53% of Americans reported wanting to cut down on phone usage, with 79% naming social media as the most addictive phone app. Roughly 70% of Gen Z reported feeling that their mental health and social life would improve with less phone time. In Meta’s own research, they found that within the last week, 70% of users reported seeing content they wanted to see less of, often multiple times and just within the first 5 minutes of opening the app. Teens echo the same sentiment. In a recent Pew study, 45% of teens report that they spend too much time on social media, and that social media hurts the amount of sleep they get. 44% report trying to cut back on their phone and social media use.

For many companies, giving people more of what they “want” just happens to align perfectly with their bottom line.

Many of us aspire to use our phone less—but the apps on our phones are designed to pull us in for more. These apps work against our better judgement, taking our attention when we’d rather be spending time with the people we love, focusing on work, or getting a good night’s sleep. For adults, this is sad. For kids, this is negligent and morally wrong.

Social scientists often discuss two kinds of decision making: fast and slow. Fast thinking is immediate, instinctive, and driven by evolved impulses, such as seeking out sugar, sex, conflict, and stimulation. But our slower, more deliberate thinking points toward different goals. Most of us don’t aspire to eat more sugar, watch more porn, see more fights, or gamble more. We aspire to eat healthier, have meaningful relationships, get along with our friends and neighbors, and have stable financial futures. The problem is that many digital products exploit our fast-thinking instincts while actively undermining our slow-thinking aspirations.

The disconnect between what people want from technology and what they’re actually getting is now widely recognized by social scientists and tech ethicists, as well as parents, teachers, and teens themselves. Around the world, momentum is building to address the harms of engagement-based and time-maximizing platforms.

In the rest of this post, I discuss four major goals for protecting kids online, and eight specific principles for crafting effective and viable policy solutions. Given the diversity of technology products, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. That’s why the Anxious Generation team has been working across a range of jurisdictions and policy levers to advance reforms that protect kids and realign tech with our considered aspirations.

Learn More About TAG's Policy Menu

We don’t let 14-year-olds sign up for credit cards because we recognize that children are still developing their ability to make long-term decisions. Yet we allow them to independently enter into contracts with large corporations—signing away the rights to their habits, thoughts and images—without ensuring they understand the implications. This lack of protection is striking, with ten-year-olds routinely lying in order to access platforms, and many younger teens often receiving unexpected and unwanted sexual content. Companies have little financial incentive to address these risks, which is why policy solutions are needed.

While the need for age verification that actually works is clear, important concerns about privacy and free speech must be carefully integrated into any policy. Any effort will require some increased data collection and could limit access to information. Policymakers, technologists and lawyers have been working to balance these considerations—often with the help of the courts—and possible solutions have become clearer. Here are four principles that can help guide policy makers navigating this challenging terrain.

Jurisdictions should feel free to limit the ability of minors to enter into legal relationships with platforms - especially when they are increasingly using that data to train AI models.

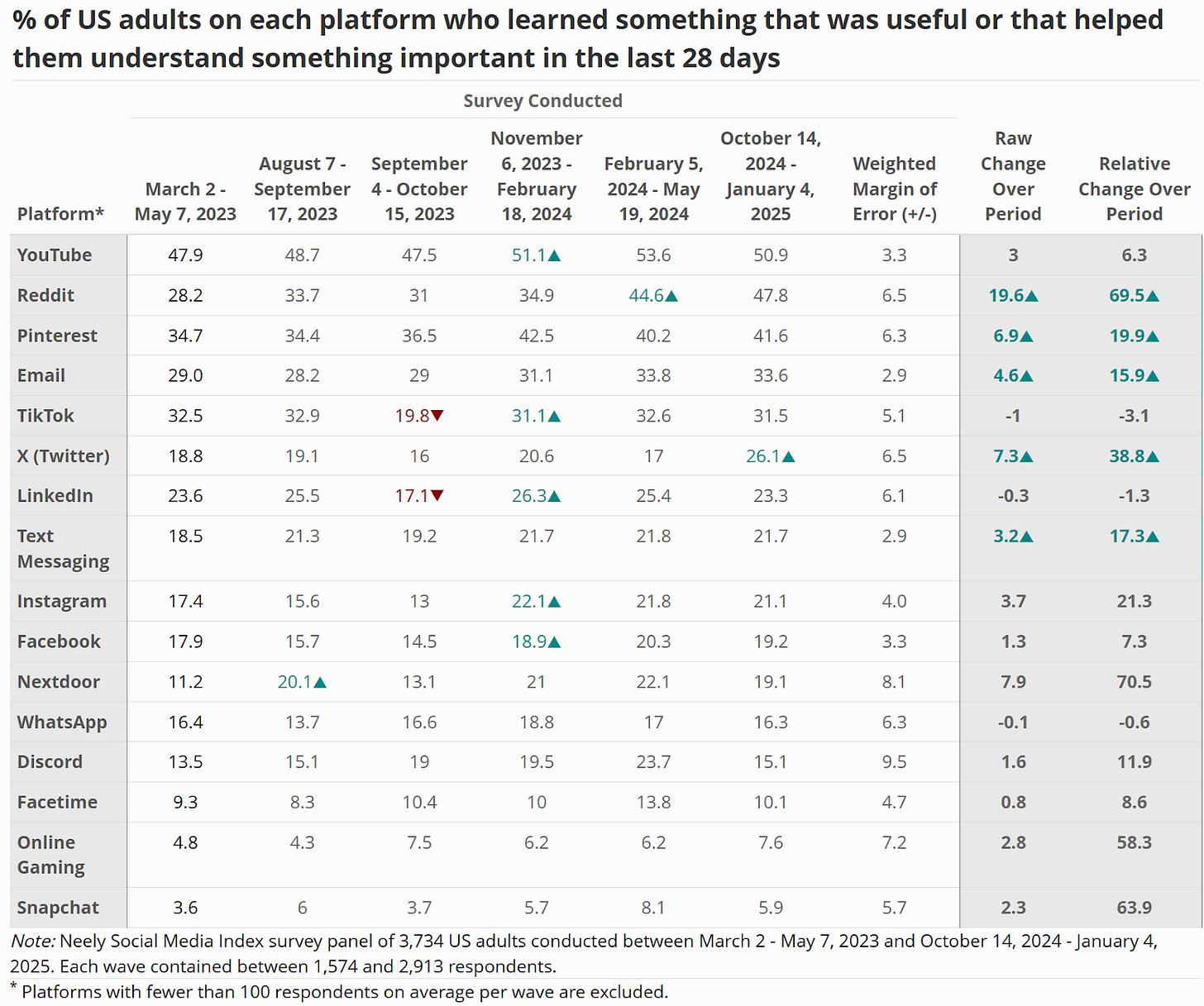

The most informative platforms do not require users to create accounts. At USC Marshall’s Neely Center, we regularly survey a representative sample of U.S. adults, asking whether they have “learned something that was useful or that helpful them understand something important.” In our most recent data, Reddit (47.8%) and YouTube (50.9%) topped the list. Both services allow access without an account, and Reddit’s rise in our data has corresponded with an increasing number of users accessing content through Google searches without logging in. This demonstrates that platforms can provide value without demanding personal data or requiring users to create accounts.

Australia’s social media age-limit legislation focuses on preventing those under 16 from creating accounts. Many European countries are following suit and several U.S. states have also considered or passed laws targeting account creation. This distinction matters: it's not access to content that is being restricted, but the legal relationships platforms create with minors in order to harvest data and increase retention. It would be very easy for Instagram to allow any teen to access Taylor Swift’s content, but it is nearly impossible to do so without getting aggressive pop ups asking you to sign up for an account that you may or may not want. Twitter/X has also gotten increasingly difficult to access without an account.

If platform’s truly care about youth access to content, they should follow YouTube and Reddit’s examples and embrace logged out access to their services. Failing that, jurisdictions should feel free to limit the ability of minors to enter into legal relationships with platforms—especially when they are increasingly using that data to train AI models.

Platforms should face a clear choice: remove the risky features, or restrict access to minors.

In Australia and elsewhere, debates are emerging over which platforms should fall under new age-limit laws. But rather than defining which services count as “social media,” regulators should focus on which features create risk.

Indonesia recently enacted comprehensive regulation to protect kids online, classifying platforms as low or high risk based on the likelihood of contact with strangers, exposure to harmful content, and engagement in addictive behavior. Messaging apps can pose risks of contact by strangers, depending on how much they encourage such connections or gamify such engagement (e.g. Snapchat’s Quick Add and Streaks features). Similar risks also exist in a variety of products that enable user messaging, even in products targeted at kids, such as Roblox.

AI-powered recommendation engines that encourage overuse of a product or that recommend engaging but potentially harmful/unwanted content are present across many apps—not just those traditionally associated with “social media.”

Through partnerships with the Knight-Georgetown Institute and the Tech Law Justice Project, the Neely Center is working to identify all the design features that increase the risk of harmful experiences to users, so that protections can target features that have been shown to cause harm. Rather than attempting to define which platforms qualify as social media, we are working to help regulators target the specific features that increase risk across online services. Platforms should face a clear choice: remove the risky features, or restrict access to minors.

Rather than worrying whether any individual app knows the age of their child and appropriately restricts contact from strangers, they can instead expect robust protections across apps and websites.

Reasonable concerns exist about how to identify children without compromising adult privacy or free speech. We may not want children to access sexual content or content about suicide, but we also don’t want adults to be discouraged from accessing such content if they seek it out. An adult may not want to provide identification in order to access sensitive content out of concern that their consumption could be tracked or exposed. Any increase in verification carries some degree of privacy risk.

To minimize these risks, both The Anxious Generation and the Neely Center Design Code recommend allowing device owners to set protections at the device level. These settings would mandate that apps respects a device owner’s preferences (including parents), such as reducing unwanted contact, unwanted content, or limiting design patterns that extend usage. Many older kids with disabilities, as well as elderly adults, would also welcome such settings. In the U.S., where parents report that social media and technology represent the greatest threats to their kids’ mental health, such protections would likely present a competitive advantage for device manufacturers who want to provide parents with peace of mind. Rather than worrying whether any individual app knows the age of their child and appropriately restricts contact from strangers, they can instead expect robust protections across apps and websites.

Beyond these settings, societies will still want to establish reasonable restrictions that are not voluntary, just as we have involuntary age based restrictions around alcohol, tobacco, gambling, driving, and voting. In those cases, the best practice is to verify age at the device level, allowing a single signal to propagate across apps and websites. Device manufacturers are already making plans to facilitate this process, meaning that new regulations will be able to rely on established processes.

Early efforts are beginning: Utah has passed the App Store Accountability Act, which requires app stores to verify ages. Buffy Wicks’ Digital Age Assurance Act in California goes a step further and requires verification at the device level. However, both of these laws could be improved by (1) allowing opt-in protections regardless of age, (2) explicitly requiring apps to retain more liability, and (3) ensuring that harmful apps are appropriately differentiated (see next section). Despite these limitations they show that momentum is moving away from app-by-app verification, and this shift should both reduce privacy risk and increase the robustness of age-based limitations.

We also caution against relying too heavily on parental consent mechanisms. App stores may facilitate consent, but if consent becomes routine, it loses meaning.

As device-level signals become available, harmful apps will have no choice but to more appropriately restrict their services. It is inexcusable that simple searches like “happy 10th birthday” still surface active underage accounts on many major platforms. These companies should also be required to use the data they already collect, often for marketing, to enhance age verification efforts.

We recommend language from Nebraska’s Age Appropriate Online Design Code:

Actual knowledge includes all information and inferences known to the covered online service relating to the age of the individual, including, but not limited to, self-identified age, and any age the covered online service has attributed or associated with the individual for any purpose, including marketing, advertising, or product development.

We also caution against relying too heavily on parental consent mechanisms. While app stores may facilitate consent, when the process becomes too routine, it loses meaning. Parents may not fully understand the implications of approving social media use. Given this risk, we would strongly encourage the removal of any requirement to facilitate parental consent, especially any that could be used to openly onboard under-13 users via COPPA-compliant processes.

Both the App Store Accountability Act and the Digital Age Assurance Act have this critical risk and we cannot support either as long as they include these provisions. Harmful apps need to be differentiated from the many innocuous apps that parents will approve of, or else we risk “consent fatigue.”

One simple but powerful way to protect children online is to give kids a true break from the digital world during the school day. Bipartisan momentum for phone-free schools is building across states as diverse as Vermont, Arkansas, Ohio, and California and in countries as diverse as Denmark, Brazil, and China.

The reason for this policy is clear: In one recent U.S. study, kids spent an average of 90 minutes out of a 6.5 hour school day on their phones. Regardless of your attitude toward technology, this represents an extraordinary waste of attention and educational resources.

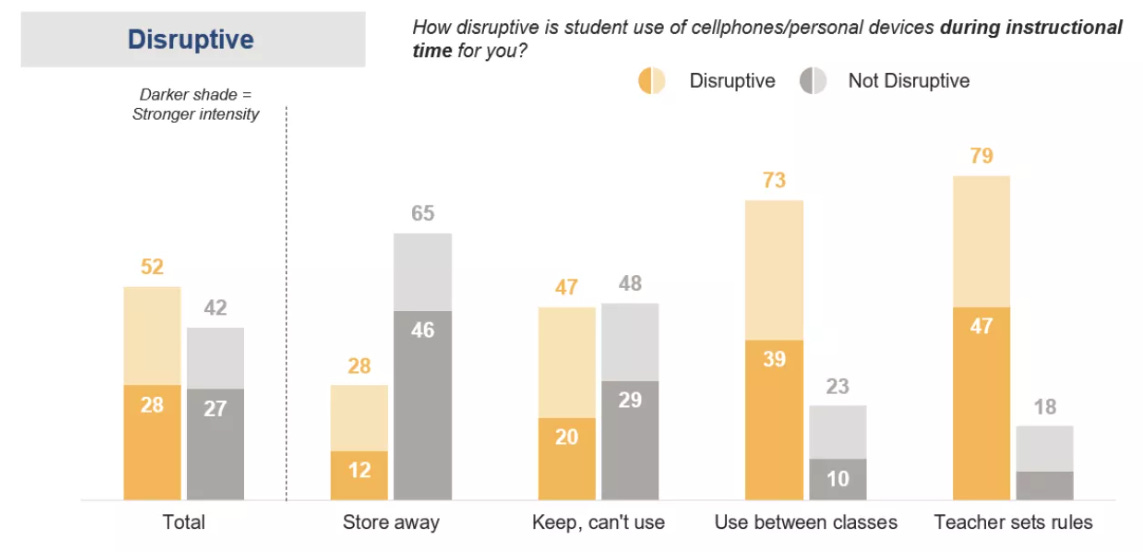

Polling shows that more than 90% of teachers support restrictions on student phone use in school, and most school districts are now implementing some version of a policy. However, these policies vary widely in scope and effectiveness.

In Texas, for instance, Representative Caroline Fairly led the Texas House to pass a true “bell to bell” phone restriction even as nearby New Mexico only restricted cell phones during classroom time. The Anxious Generation team has partnered with the USC Marshall Neely Center, Fairplay, the Becca Schmill Foundation, the Phone Free Schools Movement and ExcelinEd to educate lawmakers on why these details matter and why full-day restrictions are far more effective than partial ones.

In places like Colorado and Minnesota where policies are allowed to vary widely across districts, we are working to make data like the graph below from the National Education Association the below (NEA) common knowledge. The key finding: Unless phones are put away for the entire day, teachers spend valuable class time asking students to put them away repeatedly.

From a National Education Association survey of teachers:

Behind every “bell-to-bell” data point in this graph is the story of a teacher who was able to move from being the “phone police” to being an educator.

Here are two examples among many:

“Greg Cabana, a veteran government teacher, remembers a time where his job as an educator felt secondary to being the phone police. “It was absolutely every class period,” Cabana told CNN. “It wasn’t the question of if students would have their cell phones out, it was just a question of how much would they?” This year, however, he’s no longer fighting that battle….

“I remember the first day I was sitting in physics, my phone was locked up in my bag and I kept reaching for it, but I couldn’t, and the only thing I could do was sit on my computer and listen,” junior Alex Heaton said. “It was so freeing,”

We anticipate that every school will be fully phone-free within a few years. Whether those policies are enacted at national, regional, district, or individual school levels, a movement has begun, and the reports from teachers and administrators are very positive. Even students seem to like the policies after a few weeks, as they realize that its more fun to talk, joke, and play with their friends than to spend free moments scrolling.

We hope that more nations, states, districts, and individual schools will take on “bell-to-bell” policies.

Understanding risky platform design is not only useful for identifying which platforms should face age limits. It’s also essential for protecting users—including many youth—who will continue to use these platforms.

No platform should be rewarded for building cheaper, less safe, and more manipulative products at the expense of their users’ long-term health and well-being.

We now know far more about how specific design choices drive specific harms. These harms generally fall into four categories:

Unwanted/harmful contact (e.g., sexual solicitation or harassment)

Unwanted/harmful content (e.g., violent, sexual, or disturbing content)

Unwanted/excessive usage (e.g., via algorithms, infinite scroll, streaks, or autoplay)

Misuse of a person’s data, images, and identity

Within this taxonomy, we’ve begun to examine the specific design mechanisms associated with each category of harm. An updated report released by the Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison connects harms to specific design features, and further research is underway to add more to this evidence base. We continue to support efforts to research and reform harmful design choices, including how we might reform algorithms and how we might measure the effects of reforms.

This growing understanding of platform design is already beginning to shape both policy and platform behavior. Meta has made steps to increase privacy for youth. Pinterest has publicly advanced the practice of prosocial algorithmic design. Reddit has leaned into being a source of information that is accessible to anyone, not just people with a Reddit account. The fact that different design choices are being made by some platforms means that it is feasible for all platforms to have privacy, design, and algorithmic features that truly serve people. No platform can credibly claim otherwise.

These design practices are now being translated into minimum design standards. States as ideologically and geographically diverse as Nebraska, South Carolina, and Vermont are strongly considering such legislation, thanks to the leadership of Rep. Monique Priestley, Rep. Brandon Guffey, and Governor Jim Pillen as well as many others. We are now working across global policy and regulatory partners to syndicate these minimum standards across jurisdictions.

No platform should be rewarded for building cheaper, less safe, and more manipulative products at the expense of their users’ long-term health and well-being.

Design standards help raise the floor. But policy makers can also raise the ceiling by creating market incentives that can lead to the more purposeful use of technology.

In Utah, the recently enacted Digital Choice Act (led by Utah Rep. Doug Fiefia) requires platforms to facilitate interoperability and data portability. That means users can more easily transfer their networks, data, and digital platforms that align better with their values. The Anxious Generation team testified in favor of this legislation because we believe that families should not be locked into platforms that do not serve their aspirations. If a particular platform no longer is serving your needs, you should be free to move your data and network to a competing platform. Over time, this kind of freedom would incentivize platforms to serve user needs, rather than business profit.

Other policy makers are seeking to improve market incentives through taxation. Minnesota, Maryland, and Washington have all considered taxes on digital platforms with the idea that the externalities of these platforms should be paid for by the platforms themselves. If 45% of teens report sleeping less as a result of social media platforms, a modest tax to pay for the cost of addressing the resulting consequences of that lack of sleep - which directly led to greater ad revenue for platforms - seems both fair and proportional to the harm.

Our goal is not only to address the well-documented risks of social media, but also to evolve our understanding to confront emerging risks to psychological well-being from technology, especially for vulnerable groups like youth.

Two of the most urgent AI-enabled risks for youth today are:

Attachment to AI chatbots

Non-consensual AI-generated imagery (aka deepfakes)

In a recent Common Sense Media study, 24% of teens reported using AI chatbots at least several times per week. We’ve already seen high profile harms emerge, including lawsuits against companies like Character.ai for deploying chatbots that seduce young users, convincing them they’re conversing with sentient beings that express love, admiration, and emotional intimacy.

Meanwhile, a recent Center for Democracy & Technology study, found that 40% of youth reported awareness of AI deepfakes depicting individuals at their school, with 15% involving sexually explicit depictions and 18% depicting offensive yet non-sexual depictions. While both of these harms affect a minority of the population, this “minority” still represents millions of youth.

We do not have to repeat the mistakes we made for social media, where we failed to anticipate and mitigate the risks.

Many in the tech industry understand this. Companies are acutely aware of the Character.ai lawsuit and many employees are seeking clear design guidelines to avoid manipulating young users. At the Neely Center, we are working to develop design principles that companies can follow, and many policy makers, including California Asm. Bauer-Kahan, are developing regulations to ensure that best practices are indeed followed.

Legislation on deepfakes has also begun to take shape, but so far has focused narrowly on sexually explicit imagery. There is much more to address. Alongside the Tech Law Justice Project, we’ve worked with legislators in Georgia (w/ Rep. Sally Harrell) and Minnesota (w/ Sen. Erin Maye-Quade) on legislation that would extend rights over a person’s likeness to all identifiable traits (e.g. voice, face, mannerisms) and to non-sexual non-consensual use. We are hopeful that by 2026, the intuitive idea that we all have some rights over our own likeness will take hold.

Modern digital technologies can be extraordinary tools. But like any tool, they can be used for good, or for harm. Innovations such as nuclear technology and drones have both saved lives and been used to kill. Social media, too, still holds the potential to connect people, educate, and amplify human creativity. But right now, most platforms are optimized not for long-term value, but short-term engagement. In a market that rewards attention above all else, we cannot expect better outcomes without changing the incentives.

That’s why reforms like device-level age verification, interoperability, minimum design standards, taxation, and other protections for youth are essential. Without them, platforms will continue to do what they have been doing: maximize time spent at the expense of mental health, privacy, and connection.

This doesn’t have to be our future.

I’ll end with a quote from Chris Cox, a longtime Facebook executive who is close with Mark Zuckerberg. Many have taken inspiration from this quote within Meta:

“Social media’s history is not yet written, and its effects are not neutral. As its builders we must endeavor to understand its impact — all the good, and all the bad — and take up the daily work of bending it towards the positive, and towards the good. This is our greatest responsibility”

The question now is: how many of today’s platform “builders” still believe this 2019 quote? If you look at some of the statements from within companies, there are people fighting for this vision. But too often, they are losing the battles to short-term incentives, stakeholder pressure, or institutional inertia. That’s why parents, educators, and legislators need to get into the fight.

We created the phone based childhood. We can roll it back, and build something better.

.png)