Here's an observation I've bumped up against while investing across Europe. Our drive to not look stupid has us missing out on great opportunities.

(6 minute read)

European venture is full of investors who haven't made a name for themselves yet. Naturally, they’re risk averse. Terrified of looking stupid. They end up all playing the same game, trying to prove themselves without failing spectacularly.

I get it, there’s a personal cost to being wrong on contrarian things. If you push something strange through IC (which requires a lot of effort) and it flops, the "told you so" count goes off. Everyone questions how you didn't spot the obvious. Do it enough times and it might be game over for your career in venture.

The challenge is magnified if you're early in your investing career. Or you're only doing a few investments per year. You don't have the flexibility to be wrong. There's too much pressure to be right.

It’s very normal for investors to ask themselves; “will the rest of the capital market fund this?”. It's a very valid question to ask. They're thinking about follow-on rounds. Will this company be able to raise a Series A, then a Series B? Who will fund this, can we identify them? What metrics need to be in place to make that happen? [0].

For anything that looks odd, complex, or hard to understand, the answer is often unclear. In ways it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Nobody backs it because they think nobody else will back it. Venture Prisoner’s Dilemma [1].

So the safer path is to stick with things that look reasonable, even if reasonable doesn't lead anywhere interesting. This is venture capital's version of "nobody got fired for buying IBM." And I worry that it's playing out across Europe. Even if you don’t deliver real returns, but you made “the right” choices, you’ll avoid extinction. And avoiding extinction seems to be the primary goal.

You see many examples in hardware, materials, and even consumer. Great European founders building valuable companies. But they struggle to get funding. Not because their business is bad, but because it’s harder to understand. There's too many variables (manufacturing, supply chain, cost structure).

Take some of our portfolio companies at Nodes, for example.

Biostream's combat wearables attempt to save soldiers' lives. Heata's cloud servers, installed in water cylinders, turn rendering heat into hot water. And Iona's drones deliver to remote islands and rural communities.

They're solving real problems with solid unit economics and brilliant founders. Yet getting them funded can (at times) be brutal.

Europe hasn’t had enough contrarian success to create the feedback loop that breeds familiarity. Compared to the proven playbook of enterprise software or fintech in London, complex sectors like hardware have too many unproven variables. Unknown variables build doubt. Complexity creates caution. Both increase the chances of the company being treated as; "unfundable."

It encourages a certain behaviour. Flocking towards opportunities where there’s consensus [2]. These are easier to understand opportunities with a clear path forward. Perhaps a playbook or two exists already. I’d consider these “rational” opportunities.

The thing is, everyone sees the same thing and competes for it. Driving up valuations and making it more difficult to secure allocation. Which, in turn, makes it harder to deliver the results you're seeking.

We end up playing Linear games in a power-law world. Doesn't that feel backwards? If we're behaving the same way as everyone else, there's no outlier potential. Instead of optimising for the rational play, shouldn’t we be optimising for being right when others are wrong?

I’d describe the solution as needing more calculated irrationality in European venture capital. More people embracing the unknown. This doesn’t mean swallowing a giant valuation because the founder is of a certain pedigree. It sort of means the opposite. Backing a founder that doesn’t have a pedigree or fit a mould. Taking a bet on an unproven business model. Funding a technology where there’s uncertainty it can even be built.

Worth noting that there’s real price arbitrage here. There’s less competition, so company valuations are often lower. Increasing the potential of outlier returns.

We should get really excited when we come across a smart founder building something complex. Unknown variables should spike our curiosity. If we can solve them (or, at least, get more comfortable with them), while others say "no", that's where the opportunity is. I’ve rarely seen a strong founder stick to a bad idea for long. However weird their initial idea might be, if you think they’re an exceptional person, just back them. Bet on their ability to navigate complexity.

There’s examples of European investors doing this already, it’s just not all that common.

Robin and Saul Klein, the founders of Phoenix Court (amongst many other things) have been investing for over thirty years. Early on, they did so with their own money. Without LPs, they could invest in strange opportunities.

That didn’t change when they took on institutional investors. From fund one, they backed M-Kopa in 2015. A hardware startup building smartphones for the African market. I can only imagine this raised eyebrows at the time. No doubt people questioned the market's readiness, competition, and the viability of hardware in Africa. And yet, today, M-Kopa has 5 million customers and nearing $400m in revenue.

More recently they’ve backed exceptionally young founders like Arlan at Nia and James at Comind (both teenagers at the time of investment). Of course, this story is still being written. But it shows they’re willing to take a bet on young talent, where I’m sure, most wouldn’t.

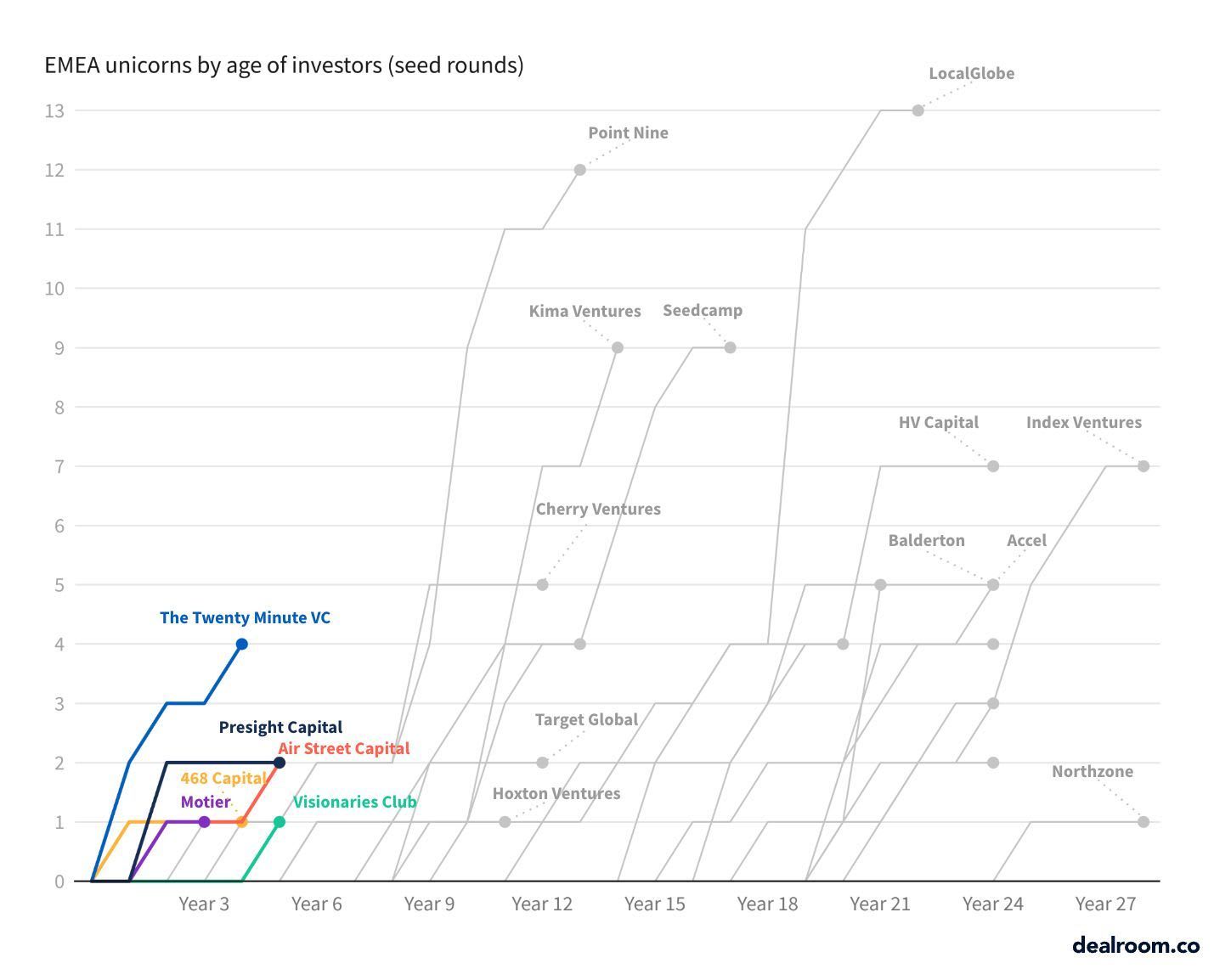

This data is a little stale, but it speaks for itself. LocalGlobe is Phoenix Court’s early-stage fund, and ranks in the top 10 globally for seed funds.

It’s a fair argument to suggest you need existing wealth or a proven track record to make these plays. I think it’s more a cultural practice. It’s a willingness to embrace the unknown a little. This starts with the LPs, and moves downstream to the analyst.

Emerging managers like Piotr, Raisa, and Leon at Material Ventures are great counter-examples here. They're not afraid to back hardware (Iona, Roli), robotics (Monumental), and consumer (Batelle). Teams like this have my utmost respect.

Perhaps a very viable strategy for emerging managers or the non-Accel’s of the world is to only back irrational opportunities. You’ll nearly always lose the linear game against them, so do something different. Your failure rate is going to be high, yes, but I’d wager that your chances of an outlier return are greater.

We need more people in the European investing community willing to stick their neck out (within reason). What does this mean in practice? Spend more time exploring the unknown variables. Take that second call. Ask more questions. Have the bravery to push back on your team. Follow your curiosity, and be willing to take a chance. And hey, if your fund won’t back it, do an angel ticket. Get involved, somehow.

Herd mentality is only going to get more pervasive when everyone is using the same tools to do their research and make decisions. Or when every fund has their own “Motherbrain” drawing the same conclusions. The bravery to zig while others zag is where you make a name for yourself.

If you're building something odd that solves a real problem (or investing in weird things), I'd love to hear from you ([email protected]).

—

Oh, and please don’t consider this yet another opinion piece on why Europe sucks. We’ve seen enough of those. This is a CTA for my peers. I’m very excited about Europe.

[0] - I’m not the biggest fan of Chamath, but he ain't wrong.

[1] - Id est, the action you choose is determined by how you perceive the other person will act.

[2] - Alex Macdonald has spoken about this a lot, so I’m not taking credit for the language here. We discussed it together in this piece.

.png)