Have you ever wondered what our curators' favourite collection items are? Here, assistant curator Lewis takes us through his rather surprising pick.

I’ve been asked many times what my favourite object is in our collection. You’d think that would be quite difficult when there are over 20,000 objects here at the Museum, and millions in the Science Museum Group’s overall collections, but it’s actually really easy. My favourite object, without a doubt, is this device that was used to resuscitate canaries in coal mines, and I’m going to tell you why.

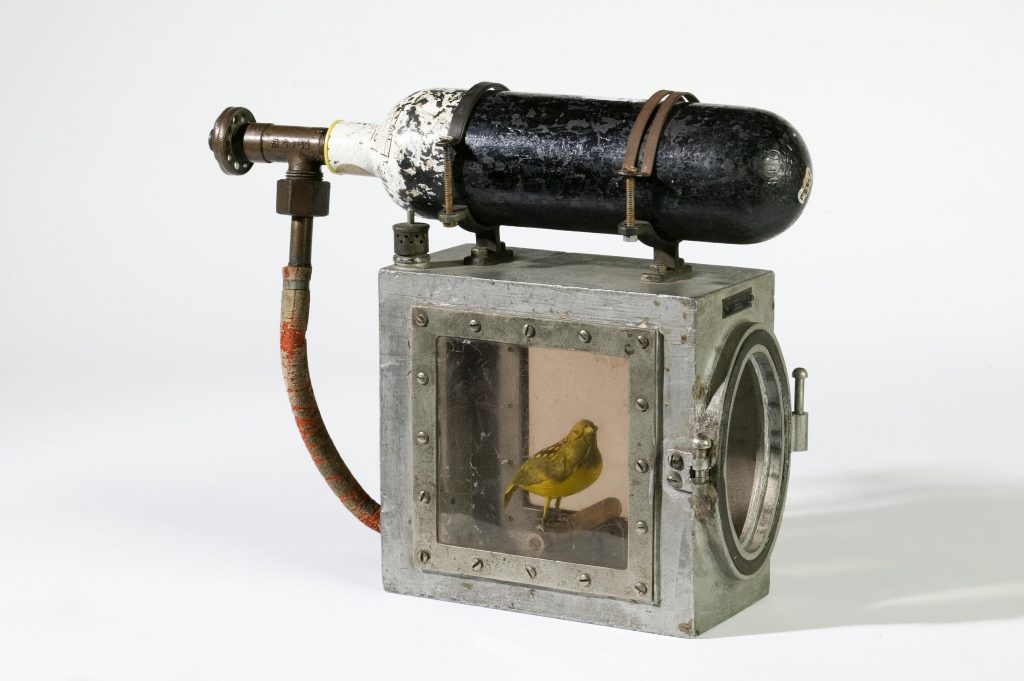

Cage for reviving canary, with oxygen cylinder, made by Siebe Gorman & Co. Ltd, London.

Cage for reviving canary, with oxygen cylinder, made by Siebe Gorman & Co. Ltd, London. View object in our online collection.

First, a little background history. Canaries were used in mines from the late 1800s to detect gases, such as carbon monoxide. The gas is deadly to humans and canaries alike in large quantities, but canaries are much more sensitive to small amounts of the gas, and so will react more quickly than humans.

This was discovered by John Haldane, who was asked to help determine the cause of an explosion at Tylorstown Colliery in 1896. He concluded the explosion was caused by a build-up of carbon monoxide and set out to find a way of detecting the odourless gas before it could harm humans. The result was this cage and its captive canary.

The circular door would be kept open and had a grill to prevent the canary escaping. Once the canary showed signs of carbon monoxide poisoning the door would be closed and a valve opened, allowing oxygen from the tank on top to be released and revive the canary. The miners would then be expected to evacuate the danger area.

So why is this my favourite object in our collections? Firstly, while I don’t advocate the use of animals in testing dangerous conditions, I am pleased that Haldane spared a thought for the canaries themselves and worked to make their job as non-lethal as possible. My impression from hearing about canaries in coal mines was that they were expected to die to warn people, so when I came across this object it was a huge relief (though my research on the topic has found less thoughtful cages).

I’ve even read that many miners cared deeply for their canary companions, and some disliked the advent of electronic sensors in the mid-1980s because it meant they would lose this companionship. Personally, I’m pleased that this practice has come to an end.

Another reason this is my favourite object is because it isn’t pristine. It’s scuffed and has clear signs of wear from use. This may sound strange, but when it comes to museum objects we often prefer the ones that are a little beaten up. They add more context and show how the object may have been used. We are able to research and understand much more from a used example than a pristine one.

For instance, here is another canary cage down at our sister site, the Science Museum:

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science MuseumIt looks great, and the canary is definitely more life-like, but in museums like ours we love an object that can tell a story. I’d rather work with one that looks like it’s seen some action, and I’m not alone in this opinion.

Our museum aims to tell the history of innovation relating to science and industrialisation, and we often show that this history isn’t a clean one. We have objects that are dirty or damaged, or perhaps represent difficult topics, and I personally wouldn’t have it any other way. If we were to scrub away the dirt, or hide the dark spots, then the histories we tell wouldn’t be true.

So, my favourite object is a mucky and damaged box, in which a canary would have been caged, and used as an indicator of dangerous conditions. It’s not pretty, and it’s cruel to the animal, but it is representative of an innovation in mining practices, and our understanding of gases and bird physiology. It lets us tell interesting histories, and it’s a great example of how scientific understanding leads to changes in industrial practices, which is one of our major themes at this museum.

Before I go, here are some honourable mentions from our wider collections here at MSI that I have a great fondness for:

Our many unusual light-bulbs, for reasons you can see here:

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science MuseumOur Cyberman costume, AKA Bob:

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science MuseumAnd our sample of Apollo spacesuit fabric, just like the ones Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin wore while walking on the moon. You can read more about Manchester’s role in putting humans on the moon in my post here:

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science MuseumIf you’d like to find out more about any of these objects, or come to the museum to research them then you can browse our collections online at http://collection.sciencemuseum.org.uk/ or email [email protected].

.png)