Angie BrownEdinburgh and East reporter

City of Edinburgh Council

City of Edinburgh Council

The teenager is one of 115 medieval bodies exhumed from the grounds of St Giles Cathedral

The first scientific evidence of the Black Death in Edinburgh has been discovered on the remains of a teenage boy who died in the 14th Century.

Plaque on the child's teeth has been found to contain pathogens of the bacteria for the Bubonic plague.

Originally excavated in 1981 from the grounds of St Giles' Cathedral, the remains have undergone new detailed analysis using advanced methods including ancient DNA sequencing, isotopic analysis and radiocarbon dating.

John Lawson, City of Edinburgh Council's curator of archaeology, said it was a "very exciting" discovery.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Construction started on St Giles Cathedral in 1124

Mr Lawson said the young male was buried with care, rather than in a mass grave which was more common for victims at the time.

The skeleton, which dates from between 1300 and 1370 - a period coinciding with the Black Death - was one of 115 exhumed almost 45 years ago to make way for steps inside the cathedral on the Royal Mile.

They have been stored in the city's archives since then.

The new work on the medieval bodies was commissioned as part of Edinburgh 900, a year-long celebration of the city's 900th anniversary.

The cathedral, which was founded in 1124, has also been marking the milestone.

City of Edinburgh Council

City of Edinburgh Council

Archaeologists excavated the bodies in 1981

Although the work has not been finished, Mr Lawson has spoken to BBC Scotland News about the discovery.

He commissioned experts at the Francis Crick Institute in London to do the DNA tests.

"This teenager has the ancient DNA of the bacteria of the Black Death, of the Bubonic plague, which is really exciting," Mr Lawson said.

The disease, which would not show up on the bones, could only be identified using modern DNA testing.

Mr Lawson said: "We know the Black Death happened but it is the fact we can now tie this person into historic events that is very exciting."

What was the Black Death?

The Black Death pandemic was primarily caused by bubonic plague.

Bubonic plague is the most common type of plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, characterised by swollen lymph nodes called "buboes".

The name "Black Death" likely arose because of the skin lesions and tissue death (gangrene) that turned the skin black in some cases.

The Black Death was a specific historical pandemic that swept through Europe between 1347 and 1353.

It was one of the most fatal pandemics in history, wiping out an estimated 50 million people in Europe.

Edinburgh College of Art/Maria Maclennan

Edinburgh College of Art/Maria Maclennan

A 12th Century man is among the medieval Edinburgh residents whose faces have been restored

Five layers of bodies were found in the cathedral's grounds - each covering about 100 years.

Mr Lawson said the discovery meant a better picture could be painted of this historical period in time.

"Without this ancient DNA we wouldn't have known how this person died and, by examining all the cemeteries in a proper scientific way, it's going to be ground changing in terms of how we understand and chart our history," he added.

The project has previously used pioneering technology by experts at Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee universities, to create facial restorations of a number of the skeletons.

Dr Maria Maclennan, a senior lecturer at the School of Design, Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) at Edinburgh University, led the work on facial restorations.

Among them was a man buried within the grounds of the cathedral in the 12th Century and a woman who was one of eight females buried inside the Chapel of Our Lady between the 15th and 16th centuries.

Two 15th-century pilgrims have also been studied.

The faces of five of them are currently on show at St Giles' in the exhibition Edinburgh's First Burghers: Revealing the Lives and Hidden Faces of Edinburgh's Medieval Citizens, which runs until 30 November.

City of Edinburgh Council

City of Edinburgh Council

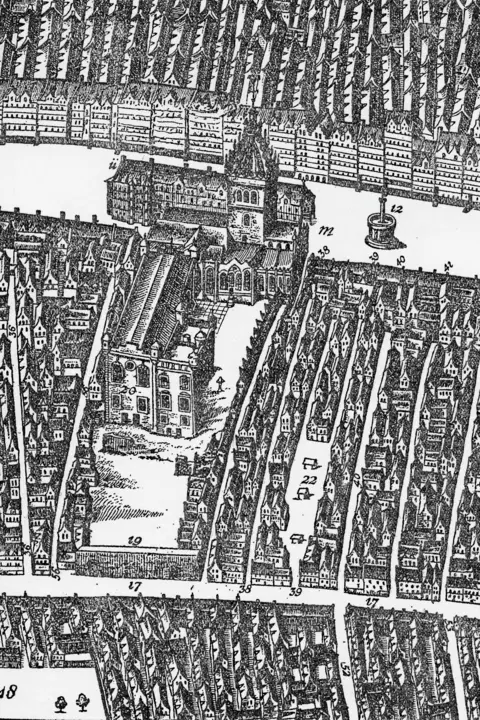

This illustration from 1647 shows the grounds of St Giles cathedral between the Royal Mile and the Cowgate

Mr Lawson said the pioneering work had even ascertained where the people, who were buried between the 12th Century and 1560, were born.

Tests have given an "amazing" insight into the lives, diets, health, origins, and identities of Edinburgh's earliest residents, he said.

Although more will be revealed once the project has been completed, Mr Lawson told BBC Scotland trace chemicals in the geology of water they drank was used to map where they were born.

He said early research shows most of the people were from the Lothians with one or two from the Scottish Highlands.

Margaret Graham, City of Edinburgh Council's culture and communities convener said: "Thanks to this exciting new research, we've been able to get a closer insight into the lives of those who existed through such a notable chapter in our past.

"As an ancient city, we have such a rich history and the discovery of a young male who may have died during the Black Death is a hugely significant find.

"I've no doubt that we have so much left to uncover and our heritage and shared stories will be enhanced over time."

.png)