Technical debt is a real thing, as any IT manager, programmer, system administrator or SRE, or end user will tell you. If you save money in the short run by not keeping up, you always end up paying with interest when you are backed into a place where you do have to catch up. Or, you go out of business.

So it is with Intel, which has come perilously close to irrelevancy in such a short time through a mix of foolishness, arrogance, and honest mistakes. For many decades, Intel was a very good chip manufacturer that also happened to be a chip designer, which just so happened to be the Intel Foundry’s only customer.

The foundry and products groups at Intel really did act like two interdependent but separate companies. The fact that the foundry business would just keep pace with upstart rival Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing was just a given in the Intel CPU products groups, even after AMD, IBM, and other chip makers abandoned their foundries because it was just too hard to keep up. And by the time GlobalFoundries (which ate the AMD and IBM foundries, among others) threw in the towel on 10 nanometer and 7 nanometer processes, leaving IBM’s Power Systems and System z businesses in the lurch, Intel was also having its own issues trying to commercialize extreme ultraviolet lithography at 10 nanometers and below.

TSMC did not falter at 7 nanometers or 5 nanometers, but it also had a bit of trouble with the jump from 16 nanometers down to 7 nanometers. In fact, the only server CPU we can find with a 10 nanometer process outside of a desperate Intel with some of its Xeons is the ill-fated “Amberwing” Centriq 2400 chip from Qualcomm, a 48-core Arm chip launched in November 2017, which was etched by Samsung. AMD used the 14 nanometer processes from GlobalFoundries (which was significantly assisted by the IBM Microelectronics acquisition) for its “Naples” Epyc 7001 server CPUs launched in June 2017, and saw the mess that was 10 nanometers and 7 nanometers at GlobalFoundries, Samsung, and TSMC and decided to jump right over it all to 7 nanometer processes from TSMC with the “Rome” Epyc 7002 processors in August 2019; AMD processed to the 5 nanometer shrink at TSMC with the “Milan” Epyc 7003s in March 2021 and has been eating Intel’s market share lunch in server CPUs since then.

IBM has been stuck in a holding pattern with Power10 and Power11 on Samsung’s 7 nanometer processes, and used 7 nanometer processes for the z16 processor chip for mainframes and shrank down to Samsung’s 5 nanometer processes for the z17 chip follow-on that is ramping now.

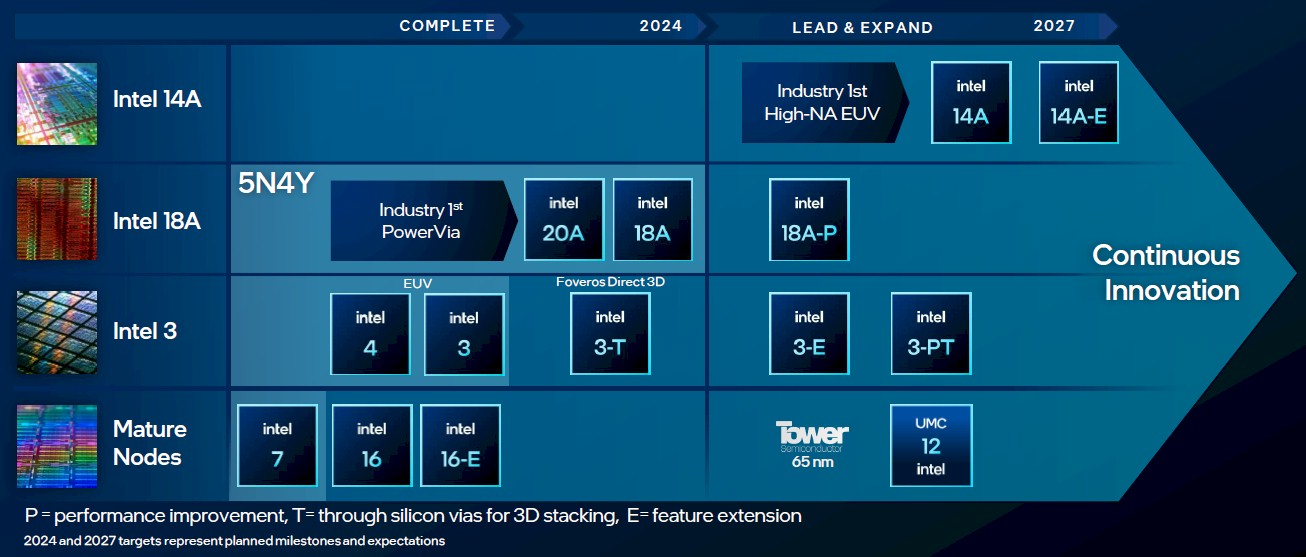

Given all of the years of delays that Intel had getting 10 nanometer processes out, culminating with Intel 7 (which is a refined 10 nanometer process), and getting Intel 4 and Intel 3 out, which we think are 7 nanometer and 5 nanometer processes, respectively, but people argue over this, you might have thought that the plan of former Intel chief executive officer, Pat Gelsinger, to deliver five new process nodes in four years to get Intel Foundry back on track was insane. And maybe it was. 5N4Y, as the effort was called, is a lot.

But what Gelsinger knows, and what his replacement Lip-Bu Tan knows, is that manufacturing knowledge in the chip business is cumulative. You can’t skip steps. You have to stand on them – or, if you trip, as Intel has done, try to land on the one after the one you skipped by accident.

Intel Foundry’s process roadmap from February 2024.

Intel Foundry’s process roadmap from February 2024.Instead, Intel tripped on the steps with its Intel 4 process, which was never used as the compute cores in a Xeon processor or in a Max Series datacenter GPU. (Intel 4 was used for the I/O dies on the “Granite Rapids” P-core Xeon 6 or “Sierra Forrest” E-core Xeon 6, which had their compute cores etched with Intel 3.

And a few years later, Intel tripped down and skipped a step again – that’s hard on the back – with Intel 20A, the company’s first crack at production EUV lithography married to RibbonFET transistors and PowerVia backside power. The 20A process was snuffed in September last year so the company could focus on trying to ramp and commercialize the 18A process.

Everyone tripped with 10 nanometers, so Intel can get a pass with that one. But if Intel wants for customers to adopt 18A, which the company says will be doing high volumes well into the next decade, and embrace the even better 14A, Intel has to go through all of the steps and not falter.

The trouble is, Intel can’t wait forever for Nvidia to decide that Intel 18A or Intel 14A is good enough to etch its Arm server processors or GPU dies indigenously here in the United States – something that we are certain the Trump administration would love to see – particularly now that the US government has a 10 percent stake in Intel. There has not, to our knowledge, been any political pressure to use the Intel foundry for nationalistic reasons, but there is no reason to believe that this will not happen starting next year as Intel gets better yields for 18A and 14A. The situation is particularly dire for 14A, which Intel said back in July may not make it if outside customers do not adopt it. Intel Products cannot shoulder the burden alone.

Intel and Amazon Web Services were talking about collaboration on 18A and 14A exploration in the Intel Ohio fabs last September, when 20A was spiked, but that foundry buildout is now stalled. AWS is getting a custom Xeon 6 processor – no one knows if it is a “Granite Rapids” P-core Xeon 6 or a “Sierra Forrest” E-core Xeon 6 – and might be working with Intel to create a fabric interconnect chip for its Tranium and Inferentia AI XPU compute engines based on 18A. (The statement was vague, and intentionally so.)

It doesn’t help that Intel’s own “Clearwater Forest” Xeon 7 E-core processor, which uses the 18A technology, which has Intel “Darkmont” Atom-style cores, and which was due this year, was pushed out back in January 2025 until sometime in 2026. Back then, Intel said the yields for 18A were progressing just fine but that Clearwater Forest had “some complicated packaging expectations” that would move it into 2026. Intel has said very little about the “Diamond Rapids” P-core Xeon 7 chips, which will use the 18A process, will be based on the “Panther Cove” Xeon cores, will reportedly have four blocks of core tiles with a total of 192 cores (that’s 48 on each tile). There is a rumor that Diamond Rapids does not have hyperthreading on its cores, which we find hard to believe. Diamond Rapids is slated for 2H 2026, and Clearwater Forest might come ahead of it or at the same time. Intel has not said.

The point is, a delay in the Xeon lineup that is not fully explained for an 18A process will taint the outside perception of the 18A process, and that doesn’t help Intel Foundry. But, then again, neither does saying that 18A chips in the pipeline have some packaging challenges.

What seems clear from all of this is that if Intel does not get some 14A customers, it is perfectly happy – well, willing, if not happy – to do future Xeons further down the roadmap on 18A or go to TSMC for cores for its compute engines using its rival’s A16 or A14 processes. If that happens, Intel Foundry will stall at 18A just like it did at 14 nanometers, and this will not be good for either Intel Products or Intel Foundry. It may be the end of the line, as 14 nanometers and its 12 nanometer refinement, was for GlobalFoundries.

Intel is in a very pesky situation, and Tan, Intel’s current chief executive officer, and David Zinsner, its chief financial officer, were pretty blunt about it. When pressed about 18A yields, Zinsner did a lot of the talking, and said this:

“The yields are adequate to address the supply, but they are not where we need them to be in order to drive the appropriate level of margins. And by the end of next year, we will probably be in that space. And certainly, the year after that, I think they will be in what would be kind of an industry acceptable level on the yields.”

“I would tell you, on 14A, we are off to a great start. And if you look at 14A in terms of its maturity relative to 18A at that same point of maturity, we are better in terms of performance and yield. So we are off to an even better start on 14A. We have just got to continue that progress.”

Well, if I was the Intel Products group, I would want 14A over 18A, just like I wanted 18A over 20A and helped kill it off. But that can’t happen this time because Intel needs to ramp a process to good yield so it can make Xeon CPUs for servers and Core CPUs for PCs profitably. No more skipping steps, either. And to that, Zinsner said that the 18A yields are where Intel expected them to be right now, and that they will improve over 2026 to get to the right cost structure.

Here’s the funny bit. Intel said that its server CPU business is supply constrained right now, and in part due to the limited capacity it has for the Intel 3 and Intel 4 processes it uses for current Xeon CPUs and also due to the shortage of substrates, which is affecting every chip maker. When demand is greater than supply, you would expect for margins to rise – one need only look at Nvidia financials to see how wonderfully this can work. And you cannot just blame the older 10 nanometer and 7 nanometer processes, apparently, which were never low-cost nodes. It looks like 18A, right now, is worse on that front.

Here is how Zinsner put it, and we are quoting him at length because it warrants it:

“I would say there are two dynamics, one of which is the high cost of older processes versus the better cost structure for the newer processes. And that’s obviously meaningful. I mean we are in negative gross margin territory for Foundry. That makes a meaningful improvement if you move it even into the positive territory.”

“But the other aspect of our gross margin is a function of just the product quality. We are in reasonably decent shape on client in terms of product performance and competitiveness with a few exceptions. But we are not where we need to be on a cost basis. And so we have got to make improvements there. And we have that on the roadmap. The team recognizes it, but that is a multiyear process to get there.”

“It is more pronounced on the datacenter side. Not only do we not have the right cost structure, but we also don’t have the right competitiveness to really get the right margins from our customers. And so we have got work to do there. And so that’s what Lip-Bu and the team has pulled in, are hyper-focused on, is getting great products at the right cost structure to drive better gross margins. That to me, I think, is the linchpin in all this.”

“The improvements on the Foundry side are just going to come, I think. We’re going to mix higher and higher to Intel 4, 3, and then 18A, and ultimately 14A. The cost structures of all of those are actually pretty similar. And it will just be a function of the fact that the value that is provided by those leading edge nodes is going to be significantly more and that is going to just materially drive the gross margins up.”

“The other thing that I would say is we are seeing a lot of start-up costs by virtue of the fact that we have jammed a whole bunch of new processes in rapid fashion. As we get into 14A, our cadence will be more normalized. And so you won’t see so much start-up costs stacked on top of each other, which is affecting gross margins. And that’s billions of dollars. So I think as you get beyond a few years, that rolls off and will also help.”

So, Intel will stop tripping down the stairs accidentally and stop jumping stairs to try to catch up to TSMC.

Which brings us all the way down to the 14A step. Who is going to use 14A?

Tan didn’t tell any secrets, but as we have said before, it may take some strong-arming from the White House to get some enthusiastic contracts for Intel. And we will not be at all surprised if we do, and perhaps in the longest of runs, this is the best thing to drive down the costs of chip manufacturing. (Assuming this is of value anymore. Such competition used to directly help millions of companies, but now it will help maybe dozens a whole lot more.) Then again, Nvidia has much higher profits than TSMC, and together, these two companies account for the lion’s share of all of the profits from the GenAI boom. Without question.

There is apparently one customer, aside from Intel Products we presume, that is very interested in 14A.

“Since the last quarter, I think our engagement with the customer for 14A increased, and we are very heavily engaging with the customer in terms of defining the technology, the process, the yield, and the IP requirement to serve them,” Tan explained. “And they clearly see the tremendous demand that they need to have Intel to be strong on the 14A. And so we are delighted and more confident. And in the meantime, we are also attracting some of the key talent for the process technology that can really drive success, and that’s why it gives me a lot more confidence to drive that.”

We will be surprised if there are not, at the very least, some gaming GPUs from Nvidia using the 14A process. And Nvidia co-founder and chief executive officer Jensen Huang may have already had dinner with Trump to layout how this might happen.

But here is the thing. Getting Nvidia to buy $5 billion of diluted Intel shares helped the Intel balance sheet, and it is great that Intel is working with Nvidia to add NVLink ports to future Xeon server CPUs so they can be a peer to Nvidia’s own “Grace” and “Vera” Arm server chips in rackscale AI systems. But Intel has walked away from the $200 billion datacenter GPU market that might be worth $500 billion by 2030, and is going to try to make do with a rackscale inference engine that doesn’t upset Nvidia too much. It is hard for us to see this as a win, even if it is what Intel has to do to survive. Clearly, Intel is banking on winning some foundry deals as the trade war with China heats up, but TSMC ramping up foundry operations in Arizona and showing off Nvidia “Blackwell” GPUs coming out id the fabs there, hurt Intel’s cause even if it may eventually avert World War III.

With all of that, let’s talk about Intel’s financial results for the third quarter, which have stopped tripping down the stairs.

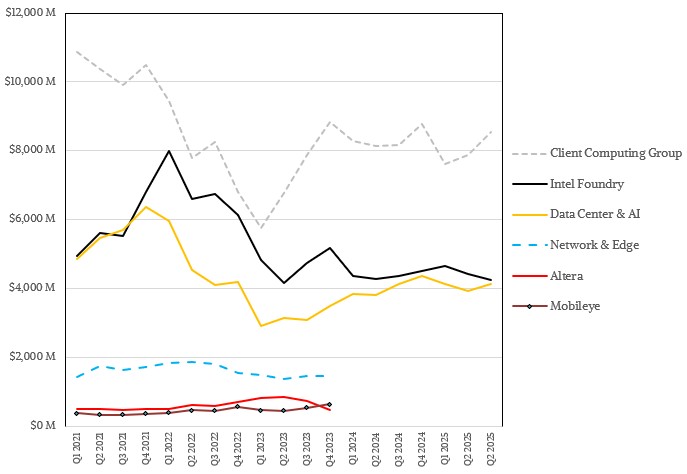

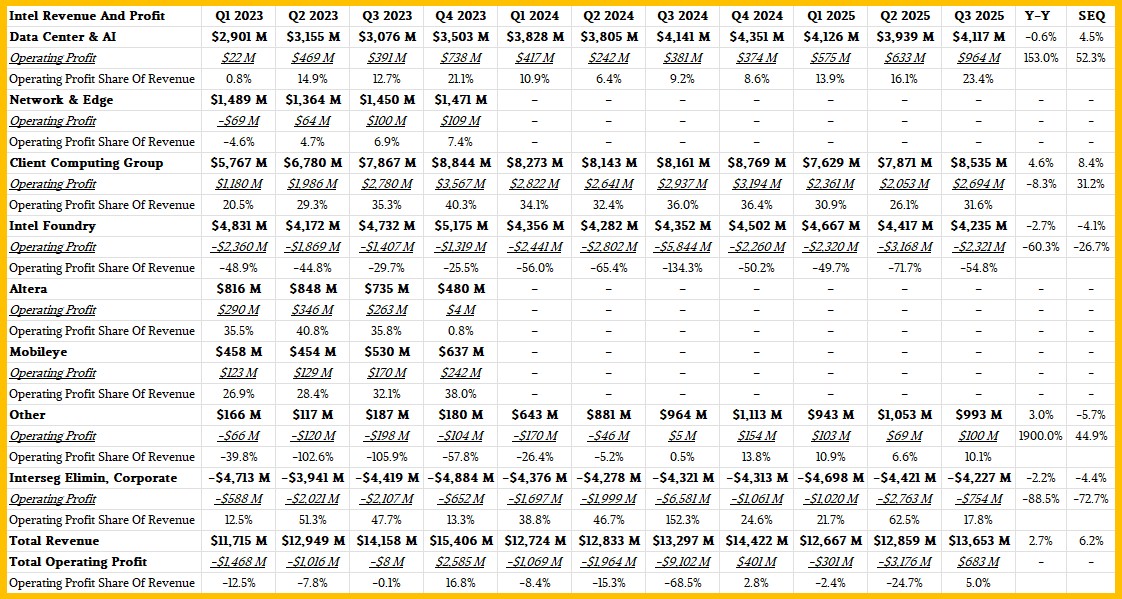

Here’s the big table of financial results since Q1 2023, when things started to get ugly for Intel:

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.With Altera sold off, some of the profits come to Intel without any of the costs, which helps. But there is also less profit coming in because it has to share with Silver Lake Partners, which is the downside. Mobileye is now part of Other revenue, and we don’t care to try to extract it and model it. It has no effect on datacenter product revenues. Network and Edge Group (NEX) has been carved up, with pieces put back into the Datacenter and AI (DCAI) and the Client Computing (CCG) groups.

Here is the same data visually:

The situation has not gotten a lot better, but it has stopped getting worse.

Intel’s revenues rose by 2.7 percent to $13.65 billion, and were up 6.2 percent sequentially, and operating profit across its groups was $683 million, or 5 percent of revenues, compared to a whopping $9.1 billion operating loss after writeoffs and layoffs in the year ago period. Net income after some infusions from Nvidia was $4.27 billion, which was a far cray better than the nearly $17 billion loss Intel posted in the year ago period.

Intel ended the quarter, after share sales of $5 billion to Nvidia and $11.1 billion to the US government, with $30.94 billion in cash. It paid off $4.3 billion in debts in the quarter as well.

Intel’s DCAI group, which sells server CPUs, motherboards, networking stuff, and some other do-dads here and there, had $4.12 billion in sales, down six-tenths of a point year on year but up 4.5 percent sequentially. Significantly, operating profit for DCAI was $964 million, up by a factor of 2.5X from the year ago period and up 1.5X sequentially. This is absolutely a reflection of better product mix and better yields on the Intel 3 and Intel 4 processes used in the current Xeon 6 lineup.

Intel Foundry is limping along with pretty huge losses, as you can see from the big table. Not as bad as Nutanix or Pure Storage had for many of their growth years, but half as bad for sure, and that is still not good.

Sign up to our Newsletter

Featuring highlights, analysis, and stories from the week directly from us to your inbox with nothing in between.

Subscribe now

.png)