Pointing out potentially misleading posts on social media significantly reduces the number of reposts, likes, replies, and views generated by such content, according to a new study co-authored by Yale researchers. The finding, they say, suggests that crowd-sourced fact-checking can be a useful tool for curbing online misinformation.

The study, which was co-authored by researchers at the University of Washington and Stanford, appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We’ve known for a while that rumors and falsehoods travel faster and farther than the truth,” said Johan Ugander, an associate professor of statistics and data science in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, deputy director of the Yale Institute for Foundations in Data Science, and co-author of the new study.

“Rumors are exciting, and often surprising,” he added. “Flagging such content seems like a good idea. But what we didn’t know was if and when such interventions are actually effective in keeping it from spreading.”

For the study, the researchers focused on Community Notes, a misinformation management framework adopted by X (the former social media platform Twitter) in 2021. Community Notes enables X users to propose and vet fact-checking notes that are attached to potentially misleading posts. Earlier this year, the social media platforms TikTok and Meta announced that they, too, are adding the same type of misinformation management framework for their sites.

Labeling seems to have a significant effect, but time is of the essence. Faster labeling should be a top priority for platforms.

Ugander and his colleagues analyzed data relating to more than 40,000 X posts for which notes were proposed. The researchers estimated that after a note was attached to a post, it resulted, on average, in 46.1% fewer reposts, 44.1% fewer likes, 21.9% fewer replies, and 13.5% fewer views.

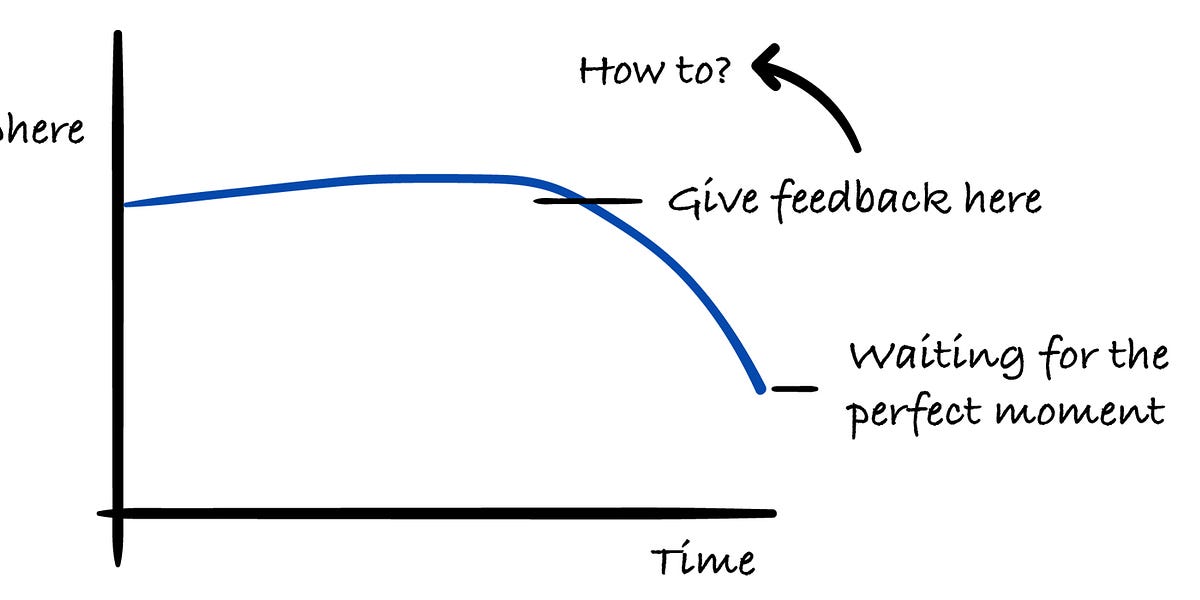

That said, the researchers also found that a lot of the engagement with misleading posts happened before the notes were attached. Over the entire lifespan of the posts, the reductions in engagement were smaller, amounting to 11.6% fewer reposts, 13.3% fewer likes, 6.9% fewer replies, and 5.5% fewer views.

“Labeling seems to have a significant effect, but time is of the essence,” Ugander said. “Faster labeling should be a top priority for platforms.”

When misinformation gets labeled, it stops going as deep. It’s like a bush that grows wider, but not higher.

The analysis also revealed how labeling appears to elicit different results for different content.

For example, labels had a large effect when the problematic content contained altered media. “Seeing altered media is a situation where a warning label can succinctly explain ‘this photo isn’t real. This never happened,’ and that can have a large effect,” Ugander said.

By contrast, when labels were added to content with outdated information, the effect was more modest.

The study was also able to shed light on how misleading posts work their way through online social networks. Warning labels were more effective when they were attached to content from accounts that readers themselves didn’t follow. The overall result, the researchers said, is that the spread of fact-checked content was still broad, but less “viral.”

“When misinformation gets labeled, it stops going as deep,” Ugander said. “It’s like a bush that grows wider, but not higher.”

Ugander added that academic research into online misinformation is of vital importance to modern society: “These platforms have a huge impact on how we communicate and lead our lives,” he said. “Adding warning labels isn’t the whole solution, but it should be viewed as an important tool in fighting the spread of misinformation.”

The corresponding author of the study is Martin Saveski of the University of Washington. Co-authors are Isaac Slaughter of the University of Washington and Axel Peytavin of Stanford University.

The research was supported in part by a University of Washington Information School Strategic Research Fund Award, cloud computing credits by Google, and an Army Research Office Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative award.

.png)