In today’s article, we had the chance to speak with Sylvain Corlay, long-time contributor of the Jupyter project, used by millions of people worldwide, and CEO-founder of QuantStack, an open-source development company employing around thirty people. QuantStack is deeply involved in the maintenance of widely used projects such as Jupyter, conda-forge, Apache Arrow, and many others.

💡

PyData Paris 2025 takes place on the 30/09 and the 01/10 in Paris.

Join developers, data scientists, and open-source enthusiasts to explore scientific computing challenges and contributions through talks, workshops, and networking opportunities. Books your tickets now !

Q: How did you first get involved in open-source, and what led you to start contributing?

I founded QuantStack in 2016, but I had been involved in open-source much earlier. I had a strong affection for open-source and was already using open-source software stacks for a long time. As a student in the early 2000s, I was a Linux user, participating in install parties and that kind of “activist” open-source activities.

Okay, kid, let's get you that Linux install you’ve always dreamed of!

Okay, kid, let's get you that Linux install you’ve always dreamed of!My real contributions started later, while working at Bloomberg as a quantitative analyst in a team responsible for evaluating financial models and methods developed internally, ranging from quantitative financial modeling to other subjects relevant to the company. We built rapid prototypes of new models and assessed their validity. It was a high-velocity team: after six months in this team, I had already implemented over a dozen prototypes.

For that, we mostly used Matlab, which is not open-source. While I loved open-source, I have to admit that Matlab’s interactive capabilities were extremely powerful. It allowed me to accomplish in a few months what would have been much harder to do back then using only C++.

That’s when I started exploring the Python ecosystem around 2012–2013, which was far less mature than it is now. There was a project called IPython, the ancestor of Jupyter, and I began developing small tools to support my work. I wasn’t contributing yet, but I was already advocating for my team to adopt this ecosystem.

From Python Terminal to IPython to Jupyter Notebooks

From Python Terminal to IPython to Jupyter NotebooksThe turning point came when the IPython team started working on the notebook interface. At Bloomberg, we were allowed to contribute to this tool, especially on widgets for small inline interfaces. That’s how I entered the project. In 2013 I made my first contributions, nothing groundbreaking, but they were accepted.

In 2014 it became more serious: we wrote a 2D interactive visualization library released in 2015, and I gradually became a Jupyter committer, moving from occasional to increasingly important contributions.

💡

Want weekly digests of the open-source ecosystem, subscribe to The Open Source Ward newsletter now!

Q: What led you to create QuantStack?

In 2016, for family reasons, I had to leave the US and return to France. I left Bloomberg on very good terms, wanting to keep working with them. I decided to create a company with a single purpose: to fund my time as an open-source contributor by selling my time to companies in my personal (mostly North American) network.

Soon, I had more business than I could handle alone, so I started hiring.

When we created QuantStack, the timing was perfect. Jupyter’s popularity had just exploded with the Notebook. Most contributors were academics or employees of large corporations, who couldn’t provide services ... That’s how we got our first contracts, even before we had a website.Bloomberg’s role in Jupyter’s development is not widely known. JupyterLab in particular was heavily funded by Bloomberg, either through employees directly paid to develop it or consultants working full-time on the project. Between 2015 and 2018, most commits to JupyterLab came directly or indirectly from Bloomberg. Later, things diversified, but Bloomberg always remained a strong supporter.

Jupyter was initially developed mainly by academics. But when you build a popular graphical interface, the required skills are quite different from those found in academia. Professionalization of the project, ensuring quality and stability was largely made possible thanks to Bloomberg and later other companies.

When we created QuantStack, the timing was perfect. Jupyter’s popularity had just exploded with the Notebook. Most contributors were academics or employees of large corporations, who couldn’t provide services. So when companies visited Jupyter’s website, they quickly found me as the go-to person for help. That’s how we got our first contracts right after incorporating, even before we having our website up.

Q: How did QuantStack grow from a one-person company to a team of thirty?

The QuantStack team, with Sylvain Corlay on the left wearing a blue t-shirt

The QuantStack team, with Sylvain Corlay on the left wearing a blue t-shirtIt was a mix of necessity and ambition. We had more requests than I or a small team could satisfy. At the same time, there was a certain frustration in not being able to tackle important challenges due to lack of critical mass.

If we wanted to do things well, to set standards, and to “win” by raising the bar, we had to grow, be bigger, more solid, more structured.

Q: What does QuantStack focus on today, and how do you see its future?

QuantStack is much more than Jupyter today. We are about thirty people, with a nearly 100% technical team, our support-to-engineering ratio is close to zero. We are truly engineering-led.

Our team includes developers of Jupyter, but also contributors to Apache Arrow (a standard tabular data format), maintainers of conda-forge, and developers of mamba (a faster conda installer), among many connected projects.

We’re no longer just reacting; we’re deliberate in our strategy. And it’s worth noting that we never raised venture capital. Back then, open-source companies were misunderstood by investors, and personally I resisted the whole startup folklore. At QuantStack, people join to stay, not for a quick exit. It’s more of a “lifetime entrepreneurship” than a scale-up, even though we’re happy to grow.

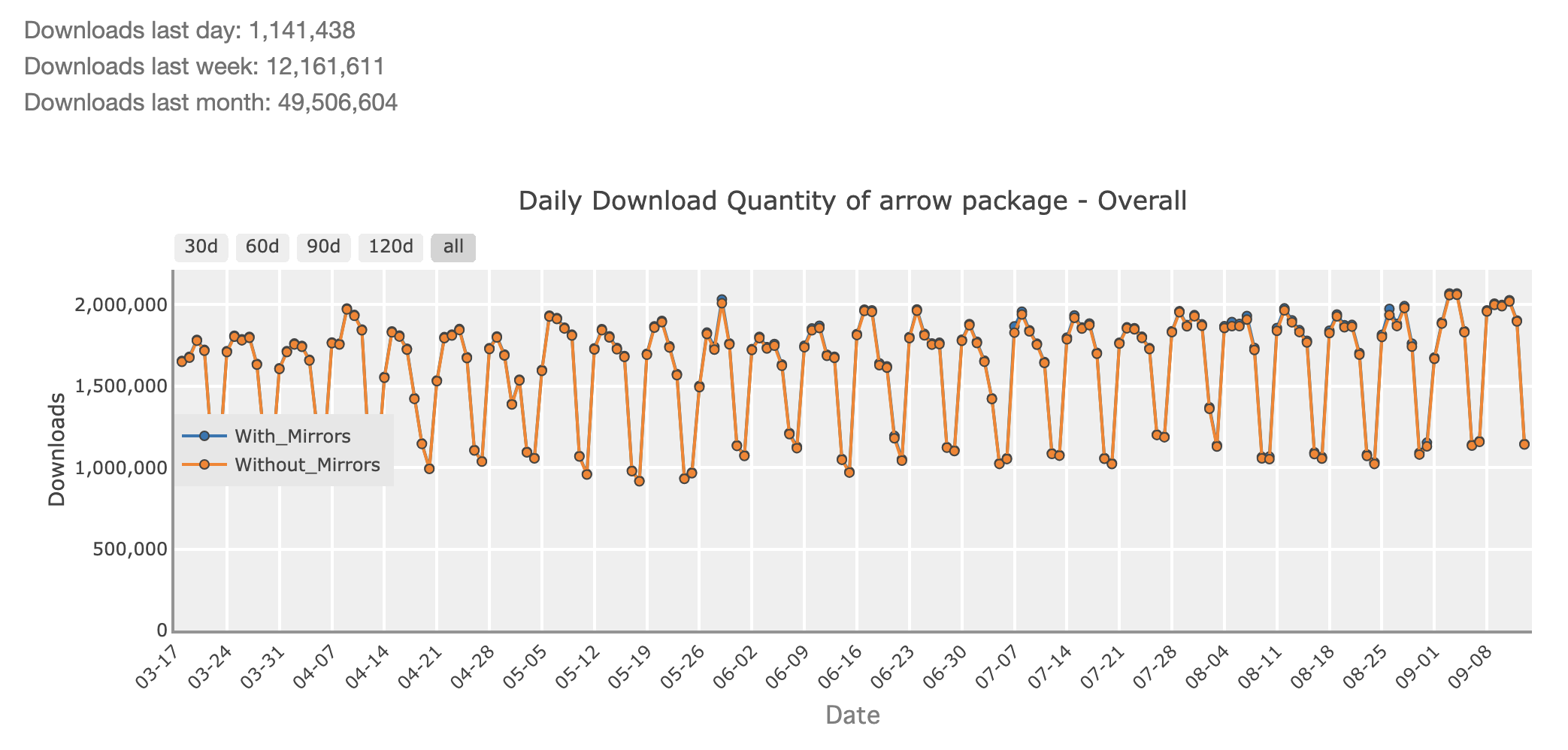

Our main reward is impact. There’s a gap between the size of our team (~30 people) and the reach of our projects. Just last month, JupyterLab had about 500K downloads per day on PyPI. Apache Arrow is three to four times more. Of course, many are automated downloads, but an IBM study estimated that several tens of millions of people use our projects today.

Apache Arrow download over time (source PyPI Stats)

Apache Arrow download over time (source PyPI Stats)For example, in France, Jupyter is deployed in secondary schools through a platform supported by the Paris municipality, with over 500,000 student users. Most kids in France learning Python do so with Jupyter and indirectly, with code we’ve written at QuantStack.

Q: How do you see the challenges of funding and governing open-source projects?

A key aspect of open-source is that projects have multiple stakeholders. They don’t belong to one company. Even if QuantStack contributes a large share, we can’t unilaterally steer a project in a completely new direction. This balance is necessary otherwise, projects risk being captured for narrow interests.

For example, conda-forge and Jupyter both have multiple stakeholders. With Mamba, one might think it competes with conda, yet conda eventually adopted Mamba as an underlying library. This is a good illustration of collaboration across supposed competitors.

Open-source development is always under peer review. Sometimes we even have weekly meetings with companies that are technically our competitors. But if we act in bad faith, we all end up cutting the branch we’re sitting on. The goal is to move forward together.

Q: What advice would you give to someone who wants to get started in open-source?

Instead of creating a brand-new project and trying to build a company around it, which is extremely difficult and dependent on adoption, you should consider joining existing popular but under-maintained projects. There are many such projects that are essential to the economy and even society, yet struggle to find maintainers.

If you become a maintainer, you can later provide services around it. Companies often outsource this kind of “infrastructure” work, not because it’s trendy, but because it’s essential.

Think of it like cities and sewers: nobody wants sewer problems, but nobody wants to maintain them either. If a company steps in, they’ll have plenty of business. The same is true in open-source. At QuantStack, we’re passionate about package management, and most of our clients are happy to outsource these “obstacle-removing” problems to us. Success is often more likely in these unglamorous but vital areas.

Q: Is there anything you’d like to add?

At the end of the month, we’re organizing the PyData conference in Paris at the Cité des Sciences on September 30th and October 1st. We expect 500–600 participants.

It’s a special week: besides PyData Paris, there will also be side events like the Apache Arrow Summit and the JuliaCon at CNAM. Developers and maintainers from around the world will gather. Instead of attending yet another LLM conference, this is a chance to discover other potential revolutions happening in the open-source world.

💡

Want weekly digests of the open-source ecosystem, subscribe to The Open Source Ward newsletter now!

.png)