I knew from my own experience that many common ways to learn a language feel productive but are a waste of time. To help my kids with French without repeating my mistakes, I went looking for scientific evidence of what actually works. This post is a summary of some counter-intuitive principles I found, and how we are using them at home with Frenchirix.

Table of Contents:

I wanted to help my kids with their French at school, but I realized I had no idea how people learn languages.

From my own experience, I knew what didn’t work. I knew how easy it is to do things that feel like learning, but are mostly a waste of time. But knowing what fails does not mean I knew what works. And I didn’t want my kids to waste their time like I wasted mine.

So I decided to try something different. Instead of falling for the latest trend in social media or getting caught up in some product’s marketing, I’d start with looking into academic research.

My thinking was that if the truth is out there:

…it’s more likely to be found in those peer-reviewed scientific papers so old they were typed on a typewriter. It must be hidden somewhere in the halls of dusty academic research departments.

Not because the hippies and hipsters who hang out there are particularly cool, but because that’s where understanding is (hopefully) based on scientific evidence that comes from things like controlled experiments with real statistical power.

And I also wanted something from papers with MRI studies:

This is how you get to the real stuff, right?

So I asked around and got in touch with people with degrees in linguistics, education, and second language acquisition. They recommended books and concepts to look up [1-5]. I read the books and researched the concepts [8].

Much of it was academics arguing with one another. Like they all mention Noam Chomsky and tell in great detail how wrong he is about everything. But I didn’t particularly care about all that stuff.

But beneath the drama, I found what I was looking for: a set of things, proven to work, that I never would have arrived at on my own.

With that new understanding, I set out to the ultimate goal: apply this to help my kids.

After some trial and error, we found this “one weird trick” that seems to work pretty well. And it wasn’t Duolingo.

It’s a double-punch:

- regular exposure to enjoyable French media that they pick themselves,

- spaced repetition of that same content.

Altogether, this could be only 10-15 minutes a day; but if it’s regular, the impact is outsized.

Getting them to watch more TV was easy: I did not get any complaints for the extra screentime.

The hard part was doing the spaced repetition right:

- You want to track what you brushed up on and when,

- You want to have some excuse to go through the dialogue again word by word,

..and to do all that without forcing it on the kid too much.

I couldn’t find a good tool for it, so I started making one myself.

This evolved into a little side project of mine called Frenchirix. The name is a spoof of Asterix (or if you are their copyright lawyer, of ancient Gallic names [6]).

This blog post is about all that.

The Science of What Works for Language Learning

You can see the list of references I read as a result of all this at the end of this post.

So if you are curious, here’s an actionable summary of what works, based on my understanding of what most of the sources and “schools of thought” agree upon, with all that other drama and fancy words filtered out.

Here it goes:

- Like Learning to Bike

- Input Before Output

- Communication Tool

- Meaning is the Fuel

- It’s Okay to Be Confused

- Use the Real Thing, not Book Language

1. Like learning to bike

We have specialized circuits in our brain for acquiring language, and true learning only happens when you engage them.

A tech person would say that the skill of communication is “hardware-accelerated” in our brains. It’s like a GPU in a computer that can only do one thing - graphics - but does it very fast [7].

What are the consequences of that? For one thing, all the heavy lifting in language acquisition is completely subconscious.

It’s akin to learning to ride a bike. It’s about giving your subconscious the time and opportunity to figure things out on its own. Your part is to just keep trying and “getting on the bike” and other than that, get out of the way and trust the process.

Consciously studying about the language (grammar, phonetics) helps about as much as physics lectures help you ride a bike.

That is, not that much, especially for kids and beginners [2, 3, 5].

2. Input Before Output

I think this particular point was the most counter-intuitive and surprising.

Brain studies suggest there is fundamentally only one way we acquire language: by practicing understanding of the input: reading and listening.

Surprisingly, it looks like producing language output —speaking and writing— are not separate skills, but are actually largely powered by the skill of input comprehension as well.

If language acquisition were a house, understanding input is building the foundation, and the ability to generate output is putting up the roof.

That means that spending too much time on output before the foundation of input understanding is built is overrated.

Another aspect of this is that it’s a good idea to hold off on constantly testing and evaluating how well a kid is doing. Soft and squishy biological things like our brains do not have progress bars that need to go to 100%.

One manifestation of this dynamic is that when babies learn their first language, they have a long “silent period” where they understand a great deal but speak very little [2].

This counter-intuitive point is somewhat hard to apply in practice for social reasons: when a person is watching cartoons, for example, and not being barraged with output exercises all the time, it doesn’t look like she’s learning.

She’s just not suffering enough.

3. Communication Tool

Understanding other people is an instinct at the core of being human. Harnessing this superpower is the only path to acquiring another language.

Yet, the important distinction is that the instinct is for using language to undertsand other people, not to do well on conjugation quizzes.

This is not how a second language is used in a school classroom, for example, where it’s not a tool to communicate but rather a peculiar activity a kid’s asked to do to please the adults.

To drive this point home, the second the teacher needs to say something truly important, she’ll switch to English [1,4].

4. Meaning is the Fuel

Our innate language learning ability is powerful and can overcome significant hurdles, but only if it’s used as a means to get to what’s catnip to our brains: the reward of understanding a meaningful and intriguing message.

Let’s spin up Duolingo or walk into a school French class.

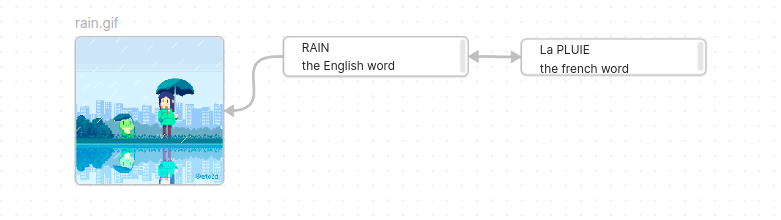

“Hier il pleuvait, mais aujourd’hui il fait beau”.

- Oh, so that means it was raining? Where was it raining?

- Nowhere in particular, it’s just an example.

- So it’s make-believe, or a lie?

- No, it’s much, much less than that.

When we work with sentence examples where the point is to translate them into English, the meaning becomes irrelevant. It’s no longer about understanding a message that relates to the world around us, Instead it’s now this bizarre puzzle of how to convert one sequence of symbols into another.

Kids are wired to be great at mapping words to meaning. Doing puzzles where you map words to some other words is not that:

Imagine Professor Pavlov putting his mind to devise another cruel experiment: conditioning his poor dogs to become bored and zone out at the first sounds of French. How would you do it?

You would flood them with sentences that mean nothing in particular.

5. It’s Okay to Be Confused

In a class, not understanding every word is treated like a failure.

But in reality, guessing from context and “winging it” is a core part of language acquisition.

We do it constantly in our native language too, mostly unconsciously.

Getting comfortable with ambiguity is part of the process. The impulse to stop and dissect every sentence you don’t fully understand is counterproductive.

6. Use the Real Thing, not Book Language

It’s often pointed out that naturally spoken French is so different from textbook French that it’s reasonable to treat them as two separate languages:

- Spoken French. The language millions of people use to communicate.

- Textbook French. A dead language for books and exercises. Like Latin.

Which one’s worth it? The answer is obvious.

And yes, if you just take any random utterance from the street said by one native to another in their natural habitat of, say, France or Quebec, it won’t be good learning material.

But that’s true for any language:

Language used in kids’ TV shows is one example of great learning material to practice that real deal: Spoken French.

When kids’ TV shows are produced, millions of dollars are at stake. Hundreds of people work on a show for years. People’s careers and mortgages are on the line.

You can be sure they’ve made certain the show is understandable to French-speaking children of various ages and levels of language mastery.

If the show is a piece of art, if it’s actually good, it’s even better. When the cinematography and voice acting are brilliant, they dialogue is no longer a bunch of foreign words slapped together; it’s the ships that bring the story: the jokes, the emotions that the characters experience, everything.

The ships with French on board being welcomed into our brain.

Why not use those?

Still, it cannot be that one-sided, right? What does Textbook French have going for it?

Most arguments about the importance of Textbook French are weak. They sound like arguments for learning Latin. We get to hear arguments involving people who died a long time ago. We are told that it’s how things have always been. We hear that the “ne” in “Je ne sais pas” must live there forever because it comes from Latin negation. And that is why those who mumble “Ch’pas” instead are despicable, uncultured low-lives we all must look down upon.

If you cast all this garbage aside, the only potentially solid argument is that Spoken French, like any other purely oral language, doesn’t have a proper writing system that serves its needs.

But let’s be honest, no form of French does.

So, I’m working on this small web app called Frenchirix.

The main idea is simple: use the French version of a TV show your kid already loves. When a kid already loves a show, the emotions do the heavy lifting. Laughing at a joke or feeling for a character opens a gate, and while that gate is open, the French dialogue sneaks in almost unnoticed. It’s no longer a bunch of foreign words slapped together; it’s part of an experience the kid already cares about.

Right now, it uses dialogue from Asterix & Obelix: The Big Fight [6], a brilliant French cartoon TV show they like.

Here’s the plan:

-

It’s a spaced repetition system for TV shows. The aim is about five minutes of practice a day, a few times a week. That’s the sweet spot: enough to actually work, but not so much that it becomes a chore. The app keeps track of what to review and when.

-

It’s for re-exposure, not for tests. The mini-games are just an excuse to go over the dialogue again. The answers are always on the same page, so if you forget something, you can still complete the exercise; it will just take a few more taps. This means kids never get stuck and frustrated. The point is getting another exposure, not passing a quiz.

-

I’m building it for my kids first. This means I get daily, honest feedback. I’ve had many ideas that I thought were clever but turned out not to work, and vice-versa. The app’s design is guided by this daily reality check, which keeps the project grounded.

-

It focuses on one thing: understanding real spoken French. Frenchirix is only for practicing the comprehension of real, native media. Doing this one thing well is the only goal.

That’s pretty much it. I’m trying to apply what the science says works, not what people expect language learning to look like.

That’s all, folks!

There you have it, my understanding of academic science about language learning, and how I am trying to apply this to my little side project called Frenchirix.

If you have any feedback, or better ideas, please email me at [email protected].

References

- Steven Pinker, “The Language Instinct”

- K.M. Hummel, “Introducing Second Language Acquisition: Perspectives and Practices”, 2nd Edition

- Input Hypothesis

- Spaced repetition

- Affective Filter

-

The website currently uses some dialogue lines from a Netflix TV show as language examples for educational purposes. As a non-commercial educational website, this use fully meets the conditions of the “fair use” doctrine in the US and “fair dealing” in Canada. Still, we all know that this has never stopped some of those companies with lawyers that need to find ways to justify their salaries. Therefore, the idea is to build a data processing pipeline that will work for any video media, not just the one currently used. This way, the second that specific copyright owners express disagreement with this particular use, the public version of this website will switch to something else.

-

And like with GPUs, things are actually much more complicated, and I do not claim to understand all this all that much. This is an oversimplification to get a point across.

-

Well, I only read the book that was written to be fun to read (Pinker’s). I skimmed and used an LLM to get the chapter summaries for Hummel’s.

.png)