I used to be an economics ambulance-chaser — someone who raced around the world to wherever there was an interesting economic calamity. And this international experience probably made me more sensitive than most economists to the way economies that seem to be doing OK can suddenly fall off a cliff into economic crisis.

In 2008, of course, America had a financial crisis of its own — and it was a nightmare. But it was very different from the emerging-market crises I used to spend so much time on. And right now I’m worried that the U.S. might be facing an emerging-market-type crisis: A “sudden stop,” an abrupt cutoff of inflows of foreign capital. If we have a crisis like that it could, in particular, cause a severe housing crash.

I wrote a month ago about the possibility of a sudden stop for the United States. Despite growing pressure on both U.S. interest rates and the dollar, we aren’t there yet. I was, however, a disciple of the late, great Rudiger Dornbusch, whose students often quote Dornbusch’s Law:

The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.

So a U.S. sudden stop still looks quite possible, indeed considerably more likely given the grotesquely cruel and irresponsible budget bill Republicans are trying to ram through. It doesn’t help that key players are being utterly dishonest about what they’re doing: House Republicans have been denying that the bill will increase the budget deficit, while Trump claims that “We’re not touching anything” on Medicaid, just eliminating waste, fraud and abuse (and somehow taking away health care for millions in the process.) Low-information voters may be fooled for a little while, but bond markets won’t.

But while I’ve already written about the possibility of a sudden stop, I haven’t said much about what such a stop, if it happens, would look like. So let’s game it out.

The starting point here is the fact that the United States runs persistent, large trade deficits:

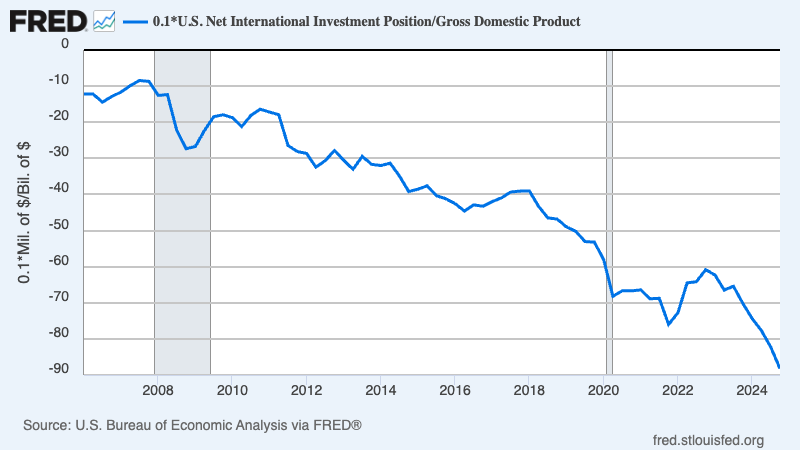

We’ve been able to cover these deficits painlessly because the world has been eager to invest in America, with large inflows of capital matching our deficit in goods and services. One consequence of decades of capital inflows, however, is that America owes a lot of money to the rest of the world. Here’s our net international investment position, the difference between U.S. assets abroad and foreign assets here, shown as a percentage of GDP:

That’s a lot of U.S. debt held by foreigners! It hasn’t been a problem in the past because foreign investors have considered America a good place to put their money. But what happens if they change their minds?

A footnote: official numbers almost certainly understate how much America pays out each year to foreign investors, because of tax avoidance. Multinational corporations that earn profits in the United States use strategies like fictitious pricing and transfers of intellectual property to make those profits disappear here and reappear in low-tax countries like Ireland.

But the important point for now is that we have a big trade deficit covered by large inflows of capital, which in turn reflect the fact that foreign investors have considered America a good place to put their money.

And the question is what happens if investors change their minds — if they decide that we’re an unserious country in which the governing party believes in voodoo economics and the president is an authoritarian ruler who spends much of his time rage-tweeting about popular musicians.

A sudden stop to capital flows into America would mean that there would no longer be money to cover those big trade deficits — and this would mean a sharp drop in the foreign exchange value of the dollar. On the eve of its 2001 sudden-stop crisis Argentina had a trade deficit, as a share of GDP, similar to that of the United States now — and when the crisis hit the peso lost more than half its value. A U.S. sudden stop would probably be less severe because our foreign debts are overwhelmingly in dollars, which insulates us from some of the fallout Argentina faced. Still, this could be ugly.

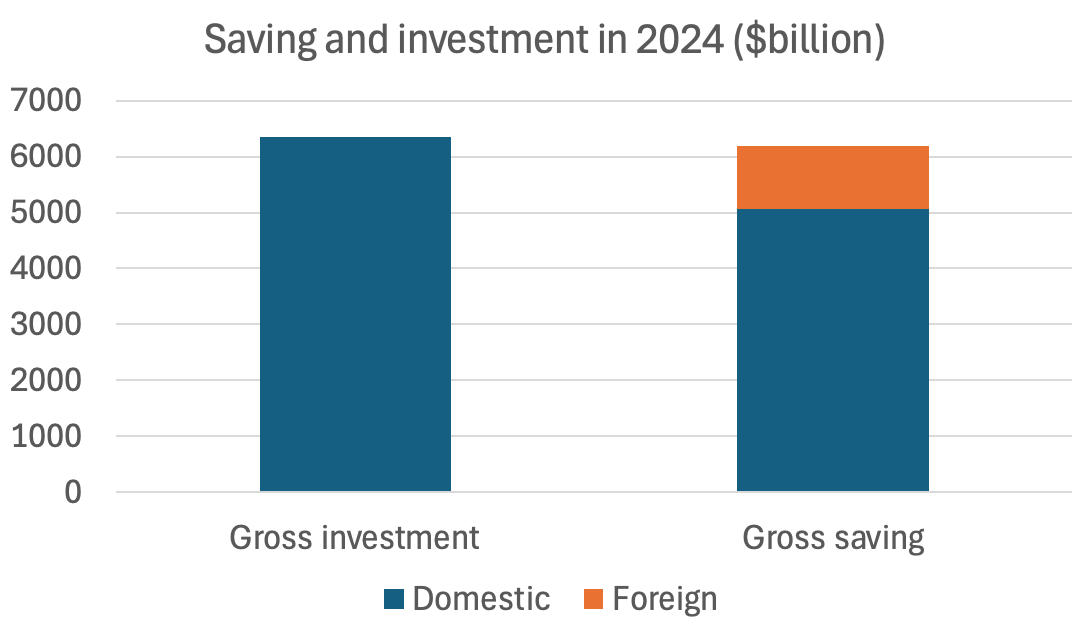

The impact on interest rates could be especially ugly. The United States relies on inflows of capital from abroad to pay for a significant part of domestic investment spending:

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Losing any significant part of that money would force interest rates higher. You have to think that fears of a sudden stop are helping to drive up long-term rates, which keep hitting new highs:

And what would be hit if interest rates surge? The answer, overwhelmingly, is housing. A sudden stop in capital inflows would mean a severe housing crash.

Would all of this add up to a recession? Housing crashes always do, in practice, cause recessions.

Some economists might argue that this time would be different, that there would be an offsetting effect from a weaker dollar, which would eventually boost exports. The crucial word here, however, is “eventually.” Historically it has often taken a couple of years or more for a weaker dollar to boost exports, because it takes time to stand up new production capacity and open new markets — especially when the Trump trade war is closing markets around the world. Meanwhile, as anyone who remembers the last financial crisis knows, housing can crash very fast.

And let’s not forget that a plunging dollar would drive up inflation, probably forcing the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates rather than cutting them despite a recession and rising unemployment.

So a sudden stop would be a very ugly experience for America — a recipe for lots of economic pain and a bout of stagflation. And recovery would be difficult. The Fed’s hands would be tied by stagflation. And to recover the world’s confidence, American policymakers wouldn’t just have to become far more responsible than they are, but they’d have to convince the world that they’d changed, a very tall order.

Now, we don’t know that we will indeed face a sudden stop. America has never had one in the past. But the danger is real, because the rest of the world is figuring out with each passing day that we aren’t the country we used to be.

MUSICAL CODA

.png)