One mistake most of us have done at some point or another, is to perform an image blurring, or downsampling on photographs, or a color gradient interpolation, without taking gamma or sRGB encoding into account (two different things, but similar enough in practice for the purposes of this article). Photographs are encoded in sRGB color space, which is the space used at display time, and which favors image compression/quality. This is different from the color space on which the real works and the objects in the photograph operate in, which is an energy-linear color space. And that difference of spaces can create problems when processing images and colors. Sometimes. And the fact that it only gives trouble sometimes makes it difficult to detect when you are a beginner, or even for decades old digital art tools.

One way it fails is when blurring images. If the blurring is done naively, your blurred image will be darker than it should, and when squinting your eyes in the original image, you'll see that the blurred one didn't respect the brightness of the original. A more technical way to say this, is that if we want the blur kernel to be energy conserving, it will have to operate in linear space rather than sRGB or gamma space where the original image is stored. So, when blurring a photograph, one should de-gamma the image pixels before accumulating them, and then probably apply gamma back to the result after averaging for display. This, of course, is something we not always do, because it's a pain and most of the times pretty slow if done by hand (thankfully most GPU hardware these days can do this for you if you choose the correct internal format for your textures).

This observation applies to box blurring, gaussian blurring, image downsampling, sobel filters, and basically anything that is a linear combination of pixel values, but it can probably be best illustrated with this simple box blur pseudocode below.

Wrong way to do a box blur:

vec3 col = vec3(0.0); for( int j=-w; j<=w; j++ ) for( int i=-w; i<=w; i++ ) { col += src[x+i,y+j]; } dst[x,y] = col / ((2*w+1)*(2*w+1));

Correct way to do a box blur:

vec3 col = vec3(0.0); for( int j=-w; j<=w; j++ ) for( int i=-w; i<=w; i++ ) { col += DeGamma( src[x+i,y+j] ); } dst[x,y] = Gamma( col / ((2*w+1)*(2*w+1)) );

Here Gamma() and DeGamma() are the gamma correction function and its inverse. These can probably be just approximations, such as Gamma(x) = pow( x, 1.0/2.2 ) and DeGamma(x) = pow( x, 2.2 ), or even Gamma(x) = sqrt(x) and DeGamma(x) = x*x if you really want to save some cycles.

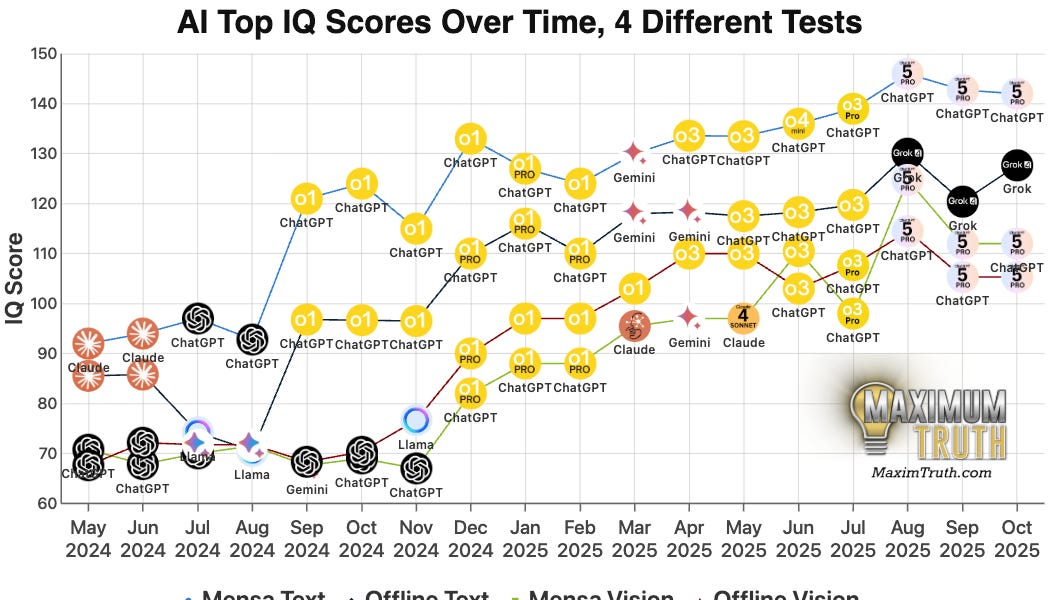

The image below shows on the left side the wrong (and most common) way to blur an image, and the right side shows the result of correct blurring. Note how the correct version does not get darker but retains the original overall intensity after blurring, unlike the one on the left. The effect is pretty obvious in the area where the bus is in the picture. The effect would be even more obvious if the correct and incorrect images were overlapping.

Left, gamma unaware blurring (too dark). Right, gamma correct blurring (correct brightness)

So, remember. If you are on the GPU, use sRGB for textures that contain photographics material and are ready to be displayed as they are. If you are on the CPU, remember to apply the inverse gamma correction. You probably want to do with a LUT with 256 entries that stores 16 bit integers with the fixed point representation of the de-gammaed value (mapping 8 bit to 8 bit would give you a loss of quality, for that point of storing images in gamma space is exactly to improve perceptual quantification quality).

You can find some reference live code here: https://www.shadertoy.com/view/XtsSzH

.png)