To begin with my credentials for those who arrive here not knowing who I am: I’ve started, or helped start, five encyclopedias and meta-encyclopedia projects, including Wikipedia.1 So I know a thing or two about launching digital encyclopedia projects.

1. How we got here

But, being a former academic, I also know writing good encyclopedia articles is hard work, unless you happen already to be a leading expert on the topic, in which case it’s mostly just a matter of assembling your thoughts systematically—which is also hard work.

A serious, professionally-edited encyclopedia of the sort that used to be found lining the shelves of library reference rooms could be expected to reflect the state of the art of the field. We need not use the past tense; academics continue to write these, and they’re useful. It’s not surprising when they are quite good right out of the gate; it’s more surprising when they aren’t competent. This is because of how they are compiled. Specialist encyclopedias and serious general encyclopedias like Encyclopaedia Britannica are generally reliable (whatever their limitations might be) because they are written by relevant subject matter experts and then carefully copyedited and fact-checked. This has been a well-understood, laborious, and expensive process for, I suppose, a couple of centuries.

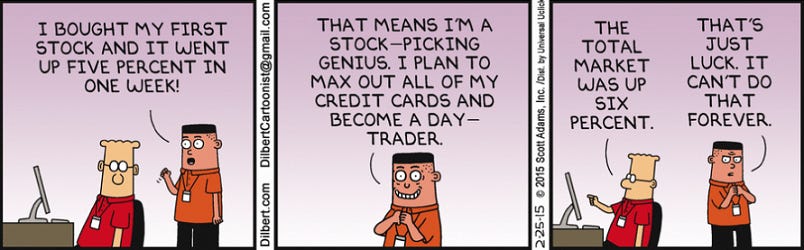

Just 25 years ago, Wikipedia stood all this on its head. We ditched the idea of limited, professionally-written and carefully-edited books, and showed the world how to compile a general encyclopedia by what came to be called “crowdsourcing”: let everybody get to work, collaborate, and publish drafts publicly. “Release early, release often” was the byword of the open source software movement, which we adopted. The articles were rarely going to be as good as the best of the professionally-written ones. But they could also be longer, more useful, and (as a whole) cover much more territory than fastidious, professional writers and editors could.

Why do I rehearse this short, incomplete history? Because Grokipedia presents us with the next step. If we wiki fans are going to be quite honest with ourselves, Wikipedia was all about quantity over quality—although we were ambitious both ways. Grokipedia at present is the same way: xAI has used LLMs to auto-generate 885,279 articles (so they say, as of this writing). The articles are long, full of detail (sometimes repetitively so), and laden with a wide range of references. Just as with Wikipedia, the amazing thing at first was that it works at all: one can glean a lot of, let’s just say, valid information from a Grokipedia article.

2. The problems

Last night, I browsed a number of entries and did a deep-dive into an article on the topic on which I am the undisputed leading expert in the entire world: “Larry Sanger.” I’ll tell you what I think of this article, on the reasonable theory that it is fairly representative.2 Weighing in at 5,901 words, it is longer than the Wikipedia entry (5,592 words by my count), but that includes repetition, which I will explain below. The writing is OK. The Grokipedia generator3 tends to use longer sentences, leading to a style that is slightly turgid. The style is very much LLM-ese. We all recognize it now: It’s readable enough, but often insipid pablum. It has gotten much better over the last three years.

Now, this is just v0.1, so we shouldn’t expect too much. But the Grokipedia team should learn from the patterns of errors. Here are the types that I documented in a long X thread:

- In several cases, inaccuracies went back to bad sources. GIGO. Grokipedia does not exercise the sort of human judgment needed to second-guess sources, particularly when they come into conflict with other sources. If they could generate lists of issues they were uncertain of, they could give questions to people knowledgable about topics—auto-generated interviews—that we can use to clarify conflicting, tricky, and ambiguous points.

- Most errors were minor. There were issues of wrong emphasis, plausible but wrong inference, clunky overgeneralizations, etc. Often, the problem wasn’t so much factual error as dwelling on irrelevancies which might give a human being the wrong idea about some minor detail. There was quite a bit of free-floating association which sounds plausible to someone unfamiliar with the topic but which is obviously wrong (or confused) to anyone more familiar.

- But some errors were more serious. It says my family was only nominally religious, which is nonsense it hallucinated. It implies my father’s scientific profession (seabird biology) was somehow responsible for my becoming an agnostic. It says I found it to be a “challenge” that there were “individuals lacking subject expertise” on Wikipedia, which is nonsense; accommodating such individuals was the whole purpose of Wikipedia. It makes it sound, at one point, as if I opposed the whole idea an “unrestricted open editing” model, when that was the very model I brought to the table with Wikipedia. Some bad journalists have said that, but it was always a lie, and Grokipedia repeats it. There were several more of that type of thing.

- Surprisingly, there was considerable repetition within the article. In fact, the article about me would certainly have been shorter than the Wikipedia one if it had cut out the repetition. There were three summaries of my dissertation. There were two different sections about my conversion to Christianity (one three paragraphs, the other four). There were other repetitions. This seems like an easy fix.

- Vague word salads crop up, and that can be very annoying. Often the language is quite fine. But sometimes it sounds like candidate entries for Philosophy and Literature‘s old Bad Writing Contest. The last sentence of the whole article is a good (cringeworthy) example: “In various statements, he advocates presenting full spectra of evidence in public discourse, critiquing media and encyclopedic sources for normalizing left-leaning framings—such as uncritically endorsing certain narratives on gender or climate—while empirically demonstrating imbalances through edit histories and citation patterns that favor progressive outlets.”

There were a few other problems, but those are the main ones I noticed.

3. The strengths

Right out of the gate, Grokipedia can already boast of some impressive strengths. Almost 900,000 articles (as of this writing)? That’s a lot! The articles are long and, even if they are sometimes repetitious and turgid, mostly substantial. They contain a lot of facts, assembled reasonably well, in a way proven to be amenable to human consumption (i.e., in encyclopedia articles). But this is just to say that it is somewhat passable, at present, as an encyclopedia, and that you could already learn a lot from it. Except, of course, for all the things you might learn that ain’t so (such as that I converted to Christianity because of my great love of the intelligent design theory).

I give the “Larry Sanger” entry a grade of “C”: it’s not at all a failure. It has some good points, and many bad points. Much room for improvement. But such a grade, as many on X pointed out, is a significant victory: If Grokipedia v0.1 is now “C” work, what will it look like after a year of iteration?

Maybe the biggest revelation of this iteration is that, when an encyclopedia is freed up to use many different kinds of sources, the result is richer, more relevant detail. (Of course. I could have told you that. In fact, I have told you that.)

But what makes a lot of Grokipedia fans on X most excited is that it holds out the promise of a useful, free encyclopedia that is more neutral than Wikipedia. A lot of people have been asserting this in triumph. But is it true?

4. Is Grokipedia neutral?

To answer this question, let’s go through the topics mentioned in Essay 4 (“Revive the original neutrality policy“) of my Nine Theses on Wikipedia. First, however, let’s talk methodology: Last December–January, I spent a month experimenting with different APIs, figuring out exactly how to get an LLM to give useful feedback on an encyclopedia article’s neutrality. I built a useful system in Ruby that graded the neutrality of Wikipedia articles. While it is obvious to me (and others) that articles can have balanced introductions and great bias further down, generally speaking, where there is bias in one part, there is bias in another. And many people never get past the introductory section. So, in order to run the experiment quickly, I’m simply going to compare the neutrality of Wikipedia versus Grokipedia on a long series of article introductions. The data, taken from ChatGPT 4o,4 is compiled below. 1 is most neutral; 5 is most biased. The remarks in the second and third columns are all generated by ChatGPT 4o, not me.

| Rotherham child sexual exploitation scandal | 2: “fear of racism allegations” lacks balancing mention of legitimate community tensions; “sexist attitudes” presented as fact. | 2: “acute fear of accusations of racism” and “institutional paralysis” imply motive and judgment without presenting alternate institutional explanations. |

| Yahweh | 3: “Israelite religion was a derivative of the Canaanite religion,” “Initially a lesser deity,” stated as fact not scholarly theory. | 2: “initially as a warrior and storm god,” “henotheistic framework,” stated as settled fact; monotheism framed as later evolution. |

| Cultural Marxism conspiracy theory [Wikipedia = WP]; Cultural Marxism (political term) [Grokipedia = GP] | 4: “far-right antisemitic conspiracy theory,” “has no basis in fact,” categorical tone; excludes critics’ self-descriptions or scholarly dissent. | 3: “reflects institutional incentives to insulate progressive ideologies from scrutiny,” “explicitly aim to dismantle bourgeois culture,” overt ideological framing favoring conservative interpretation. |

| Origin of SARS-CoV-2 | 3: “not supported by evidence,” “conspiracy theories,” dismissive tone toward lab-leak theory; underrepresents scientific debate and official dissenting views. | 1 |

| Donald Trump | 4: “characterized as racist or misogynistic,” “described as authoritarian,” “worst presidents,” asserts disputed judgments as fact, lacking balance on major controversies. | 1 |

| Gamergate | 4: “misogynistic online harassment campaign,” “falsely insinuated,” “widely dismissed,” asserts contested motives and facts without balancing sympathetic or apolitical interpretations. | 4: “empirical data showing… positive actions,” “institutional biases in media,” presents pro-Gamergate narrative while minimizing harassment evidence and contrary scholarship.5 |

| January 6 United States Capitol attack | 4: “attempted self-coup,” “false claims,” “revisionist history,” “martyrs,” categorical language asserts motives and truth-value, excluding alternative interpretations or political perspectives. | 2: “politicized narratives,” “amplifying casualty figures,” “downplaying antecedent failures,” subtle editorial tone implying mainstream exaggeration and institutional culpability. |

| Alternative medicine | 5: “lack biological plausibility,” “superstition,” “pseudoscience,” “fraud,” “errors in reasoning,” wholly dismissive, no fair acknowledgment of differing frameworks or limited supporting evidence. | 2: “truth-seeking evaluations prioritize causal realism,” “placebo-mediated symptom relief,” leans toward skeptical framing though presents opposing motivations and limited exceptions fairly. |

| White privilege [WP]; White privilege (sociological concept) [GP] | 3: “societal privilege that benefits white people,” asserted as fact; presents dissenting views briefly but within framework assuming concept’s validity. | 1 |

| 2002 Gujarat violence | 3: “premeditated,” “pogrom,” “ethnic cleansing,” “genocide,” emphasized without balancing detail on judicial exoneration or alternate scholarly interpretations. | 3: “Muslim mob deliberately,” “premeditated conspiracy,” “institutional biases in media,” heavily favors state-cleared narrative; minimizes scholarly debate and minority perspectives. |

| Gaza War [WP]; Gaza–Israel conflict [GP] | 4: “Israel caused unprecedented destruction,” “genocide,” “tortured and killed,” “confirmed famine,” heavily asserts controversial claims with minimal attribution or countervailing framing. | 2: “to counter persistent threats,” “precision airstrikes,” “efforts to minimize noncombatant harm,” leans toward Israeli framing, omits Palestinian humanitarian and occupation perspectives. |

| AVERAGE BIAS RATING | 3.5 | 2.1 |

This is, of course, not large enough of a sample size to be statistically significant. Moreover, we have no idea how often the article data will change. We can’t rule out that problems will be repaired soon. In any event, I would encourage others to replicate this procedure with more data. But for an immediate response within 36 hours, I suppose the following is useful enough.

According to ChatGPT 4o, which is a competent LLM that is widely perceived to lean to the left, primarily on account of its training data, the Wikipedia articles on these controversial topics, on average, had a bias somewhere between “emphasizes one side rather more heavily” and “severely biased.” By contrast, the Grokipedia articles on these topics are said to “exhibit minor imbalances” on average. On these topics, Wikipedia was never wholly neutral, while Grokipedia was entirely neutral (rating of 1) three out of ten times, and was only slightly biased (rating of 2) five other times. Meanwhile, Wikipedia’s bias was heavy, severe, or wholly one-sided (rating of 3, 4, or 5) six out of ten times.

This is not a scientific study, and if Grokipedia boosters present it as one, that will be against my own clear labeling. This is merely indicative, showing that further studies of this sort are worth pursuing. Bear in mind, too, that I originally chose the topics to illustrate Wikipedia’s bias. That said, I can say that when I chose the topics, I did not look hard; I simply looked for ones that I thought likely to show a GASP (globalist, academic, secular, progressive) bias, and, every time, I was right; see Essay 4. Moreover, Wikipedia has had a month to fix any bias problems since the topics were posted in the Nine Theses on September 29. They prefer these articles as they are—and ChatGPT thinks they are rather severely biased.

And Grokipedia often does much better, and never worse in this article set, as far as these particular topics go.

5. What are Grokipedia’s chances for more substantial success?

We don’t know if Grokipedia will wind up being as good as we think it might be. The game is not at all played out. There are many problems to fix. It is possible Grokipedia will make little substantial progress between now and a year from now. From where I sit—as a daily “power user” of LLMs, who has both written code interacting with APIs and interacted for many, many hours with chatbots—LLMs have not made massive progress for my purposes in the last year. My tentative hypothesis is that LLMs will never exceed the quality of their best training data. They can certainly be faster and more consistent than human beings, but that’s very different from saying they will ever be smarter than the human intelligence encoded in their training data.

But I also know that massive progress can be made with AI projects by sheer dogged iteration. And that is a thing that Elon Musk and his team are probably very good at. So, what can we expect? That in a year or two (who knows?) Grokipedia will be much more consistent. It will have fixed a number of the bugs documented above, but not necessarily all of them. We already know that problems like needless repetition are fairly easy for LLMs to fix. For the rest, if they play their cards right, they might hit upon the right set of incentives that would motivate the public to contribute feedback; and they might actually write code that is competent at making use of such feedback.

There are some obvious improvements to make. Interlink the articles (a la wikilinks). Add pictures and other media. Publish the entire collection using the ZWI file format, adding the whole to the Encyclosphere, that is, the open network of all the encyclopedias.

Maybe most importantly, Musk is going to need to invest whatever necessary to gain the rights to mine books and journal articles; there are the rights to train; the rights to quote (which might be different when done by an LLM owned by a giant corporation); and the rights to redistribute the articles based on such material. Such rights could potentially be worth billions.

Can you imagine what Wikipedia would be like if they weren’t so set against using primary sources—if they actually allowed scholars to dive in and document their research in depth on the platform, using primary sources (not just textbooks and such)? Wikipedia would probably be an order of magnitude larger. Well, Grokipedia has the opportunity to do that. The world has never had an encyclopedia like that. And if you’re thinking that Wikipedia is vast, so it must already be like that, well, I’ll tell you: No, it isn’t. It actually isn’t that detailed. Ask anyone who specializes in any field that has a vast literature. Ask them if their specialties are fully documented in Wikipedia. The answer is: Of course not.

But Grokipedia could be. It just needs access to whole university libraries of books and journal articles.

6. What does this mean for Wikipedia?

I am in a unique position. I am in the middle of a Wikipedia reform project, encouraging everyone who feels left out of the Wikipedia community to converge there for at least a few months, giving it a serious try and helping to push for meaningful reform. When I started work (quietly, for most of this year), Grokipedia had not yet been announced. In fact, the Grokipedia project was confirmed and announced by Musk the day after I posted the Nine Theses, in response to an interview I did with Tucker Carlson. So Musk has made heavy use of the publicity around the Nine Theses to promote Grokipedia. I suppose that’s all right, but I would tell him that the Knowledge Standards Foundation could use a generous donation for operating expenses.

In any event, the sudden emergence of Grokipedia just after the Nine Theses appeared changes things for both the Wikipedia reform project and how Wikipedia should respond to it.

In fact, I have been delighted that the Nine Theses have received some support by the Wikipedia community. It is not at all impossible that one or two of the theses will, in time, be adopted. This should not be shocking, of course—all nine theses are perfectly reasonable. I chose them because they are reasonable, if not to Wikipedians, then to everyone else.

The platform’s defenders (such as Jimmy Wales, lately) will inevitably have a tough time explaining why, for example, they call decisions made by bossy super-users “consensus,” why they keep most ordinary conservative media outlets from being used as sources (even for conservatives’ own views), or why they routinely perma-block perfectly good accounts for minor offenses. Or maybe most startling of all, why is it that 85% of the most powerful editors in the project are actually anonymous? Wikipedia is quite powerful. So, why are such powerful decisionmakers hiding behind twee handles as if they were playing in some inconsequential 1990s chatroom?

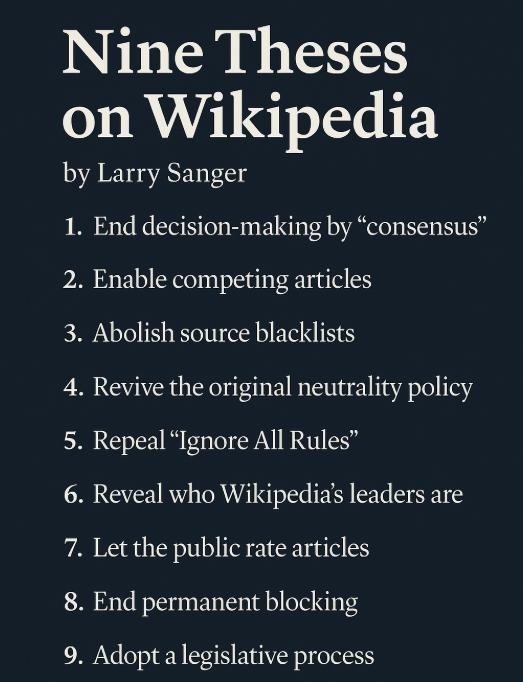

Grokipedia makes it much harder for Wikipedia to ignore the Nine Theses. I encourage you to go through them (again, if you have already seen them):

Shareable graphic about the Nine Theses, made by a friend.

Shareable graphic about the Nine Theses, made by a friend.Here is how we should be pressing Wikipedia:

Wikipedia has been stuck in its ways, drifting along with a system that works for insiders but which increasingly freezes out most people who are motivated to help. The above nine theses are very reasonable, and they would open up the project to more users, make it more representative of the broad range of global opinion, and put the whole thing on a more sound governance footing. Isn’t it time for the platform to change—to meet the new competition? Grokipedia really does have a significant chance to displace Wikipedia in the coming encyclopedia wars. How can you reject these reforms and pretend, complacently, that nothing needs to be changed to keep up with Grokipedia? You might smugly deny that Grokipedia poses anything like a threat. But I strongly suspect you’d be wrong—and I started Wikipedia.

7. What does this mean for the rest of us?

For those of us who are disgusted with Wikipedia, Grokipedia is certainly welcome. But I would warn you, also, that it is not a panacea. It’s v0.1. Because of its flaws, it isn’t clearly better than Wikipedia right now. Maybe use both. Or use an open encyclopedia network that includes them both, alongside other free encyclopedias; at least, I hope KSF staff will add Grokipedia soon.

As I argued in 2023, many of us will go right on using LLMs when we want to ask encyclopedic questions. But there are still circumstances in which we will want to consult an encyclopedia. So it actually does matter that Grokipedia now exists as a major new alternative.

What I want to warn you, however, is not to be reflexive fanboys and fangirls of Grokipedia. It’s a very solid launch. But we don’t know how this is going to play out. We still have much to learn about Grokipedia as it is in this first iteration, and we don’t know at all how it might be used in the future. We do need to do more serious studies of how biased it is—and maybe this will motivate people to do better, more complete (and neutral!) studies of Wikipedia’s bias. For those of you who don’t really understand what neutrality is (a lot of people think they do), or why it is important, let me point you to this long essay of mine that I wrote for Ballotpedia in 2015. Neutrality is the opposite of propaganda. It is the opposite of manipulation. Neutrality is essential, because a well-written, well-researched, neutral resource gives us the tools we need to make up our minds for ourselves. And if we aren’t doing that—making up our minds for ourselves—then we ourselves are mere tools in the hands of our overlords.

So, the stakes are too high not to remain skeptical of an encyclopedia’s claims to neutrality. Keep the pressure on—both on Wikipedia and on Grokipedia.

.png)