Welcome back!

We’re Ron & Spencer: two engineers who met during YC’s S19 batch obsessed with how atoms move through the world and why most software folks still treat factories, power plants, and construction sites like exotic animals in a zoo.

We’ve merged into one publication.

You probably subscribed when Ron shared the shutdown of his multiplayer browser, Sail / Muddy or from when Spencer ran Rent the Backyard, a $10 million-revenue experiment in factory-built housing that crashed head-on into real-world supply chains and interest-rate whiplash.

This blog is our field journal. Expect operator’s-manual takes on U.S. manufacturing, energy infrastructure, and deep-tech business models — written for people whose feeds still overflow with software takes, but whose curiosity has drifted toward things that weigh tons. We’re not here to dunk on SaaS (we love a good gross-margin chart), but we do want to decode the playbooks that actually work when your MVP shows up on a truck instead of in a browser tab.

If that sounds like your idea of fun, join us!

First up: why some of the biggest opportunities in hard tech look less like SaaS flywheels and more like high-grade gold mines — and how not to blow yourself up while you’re swinging the pickaxe.

- Ron & Spencer

But Rung, you’re rich — you’ve got everything. Ladders! Ascots! Why did you need [to steal] a diamond?

I inherited a ladder company. We make the one product in the world that no one ever replaces! Ladders don’t wear out like TVs or personal trainer over 40.

Oh no. They’re built to last which means no sales. Company’s broke!

- Fred Jones & Rung Ladderton, Season 1 Episode 3: Scooby-Doo! Mystery Incorporated

The Scooby-Doo ladder magnate isn’t just a cartoon punch-line, he’s a warning label. For forty years, Silicon Valley has been trained to worship businesses that compound indefinitely: SaaS dashboards that bill monthly, network effects that snowball, and margins that expand with every extra user.

Deep-tech plays in larger markets than SaaS but by a very different rulebook. Many businesses look less like revenue compounders than process compounder and the revenue you do have looks like a discovery of gold. Finding gold is rare and it’s not necessarily a given you can strike it twice.

I have first-hand experience with this, because I ran a gold mine: Rent the Backyard. which built ADUs (backyard homes) across the San Francisco Bay Area. The mine was deep (>100,000 suitable backyards in San Jose alone) but obviously a mine. We weren’t particularly worried about exhausting the market though — ADUs were our initial way to build affordable housing.

At just over 400 square feet (40 square meters), we thought of our ADUs as “minimum viable housing” we could quickly get cost effectively reps building. Built with a flat roof from cross laminated timber, we envisioned combining modules into larger single units or stacking them into multifamily units.

Spoiler: We were killed by small scale production and interest rates, not by running out of gold.

Once you start looking for them, gold mines are remarkably common. Physical installations, financial / technology arbitrage, and products well loved on “r/BIFL” (Buy it for Life) all share the same defining characteristic:

- One-and-done customers: You sell to a customer once. There's no LTV (Lifetime value) calculation, no upsell path, no recurring revenue from the core product. The entire economic value of the relationship is captured in a single transaction.

This leads to

- Depleting TAM: every sale by you (or a competitor!) reduces the potential customers for your product.

- Depleting customer quality: just like a real miner you go after the more accessible and profitable seams of gold first. Subsequent customers are further from your ICP (ideal customer profile), your sales process gets more difficult, and margins decrease as you grow.

- Gold rush: running the business isn’t about growing the pie, it’s about gorging yourself until it’s gone. If you don’t already have competitors they’ll be here soon.

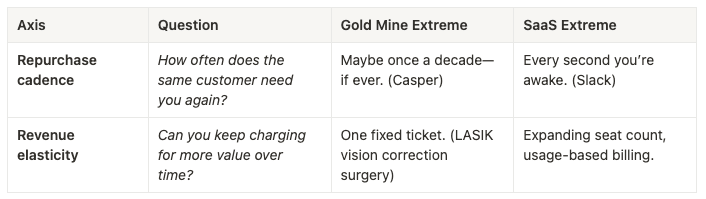

Most real-world businesses sit somewhere between a pick-once gold mine and an always-on SaaS subscription. Two variables matter more than anything else:

The easiest way for most software companies to grow is by increasing revenue from existing customers. Gold mine companies don’t do this!

At Rent the Backyard, we were often encouraged to sell homeowners ancillary or reoccurring services like property management or insurance. Unfortunately, commissions from $50 / month insurance or even $200 / month property management couldn’t move the economics on a $200,000 ADU purchase. Solar panels or battery systems might have been a little better but there wasn’t a conceivable way to double or triple the margins on an installed project.

Casper spent millions trying to improve the economics of its $1,000 mattress business by selling $50 pillows. The business was bought by private equity for 1/3 its IPO price after two years on the NYSE.

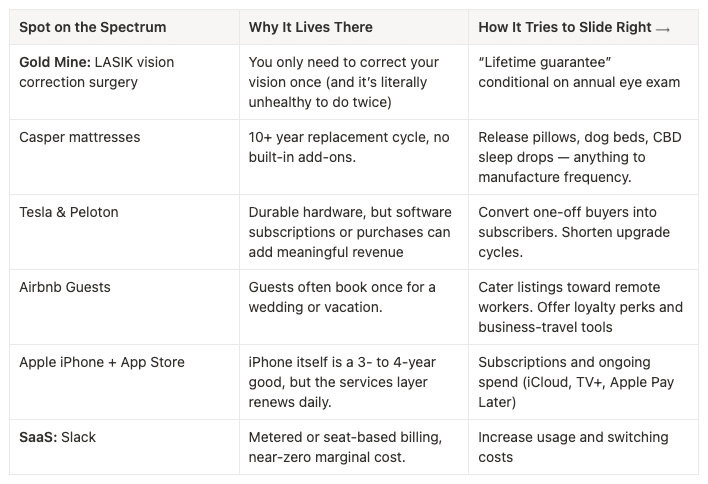

At both companies, it was much better to invest in the core product than ancillary revenue but all companies exist somewhere on the spectrum between mining for gold and selling SaaS.

As residential solar panels first became available in the early 2000s, companies like Sunrun and Solar City (now owned by Tesla) were textbook examples of a gold mine business. Massive sales teams went door-to-door signing up homeowners for “solar lease” loans to put solar panels on their roof to save on their utility bills. It was an easy sell: your monthly payment on the solar panel was less than what you’d save on electricity.

At first the market was a true gold mine. There were a finite number of correctly angled, suitably sunny roofs owned by people with good enough credit. Once a house got a solar installation, it was off the market.

But then solar kept getting cheaper.

The Y-axis (cost per watt) is a log scale 😳

The number of homes solar leasing companies could service rapidly expanded giving the companies more TAM to mine but the costs kept dropping. When Sunrun was founded in 2007, a 7 kW system to power a 2,000 square foot house cost ~$60,000. In 2025, that same system would be only ~$14,000.

Unfortunately for Sunrun, low prices also meant consumers didn’t really need to finance solar panel as much either. Sunrun’s stock is about the same price as when it IPO’d in 2015.

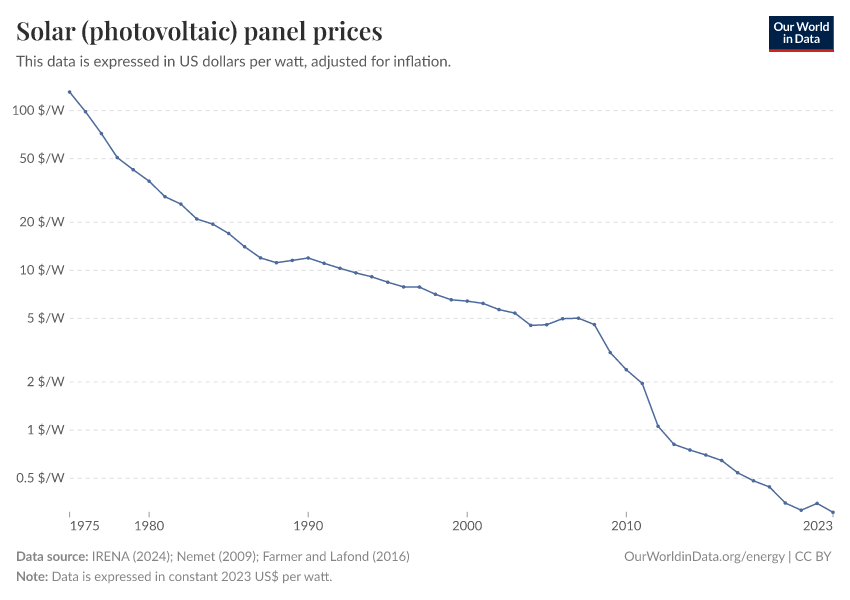

If you realize you're running a gold mine, you have to fight the instincts you've learned from reading about or running typical venture-backed startups.

The single biggest error a gold mine company can make is subsidizing customer acquisition. As a gold mine company, you will make ~all of your money at the time of acquisition or on some short half life thereafter.

The easiest way to recognize a startup that doesn’t know they’re a gold mine business is to see them losing money on CAC. In a normal startup, you might justify that with high LTV or !network effects! But here, the transaction is the beginning and the end. There is no "later" to make it up on volume. You are just lighting money on fire.

The lifecycle of many gold mine company can be brutally compressed: Growth -> Plateau -> Decline. You have to be ruthlessly honest about which phase you're in. If you're in decline, you can look for clever ways to reinvest in growth or new business lines, but you might never find anything as good as the original business!

It’s okay if you can’t find anything worth investing in but your job becomes gracefully managing decline and creating the best outcome for your stakeholders, employees, investors, and yourself.

Without a growth story, declining companies have a share price that’s hard to predict but presumably decreasing. While conventional wisdom is now that buying back stock is mechanically ~identical and more tax efficient than issuing dividends, this only applies to companies with a flat or rising market capitalization!

The worst mismanagement of a declining company? IBM:

The company spent ~$200 billion buying back their stock between 1995 and 2019. As recent as November 2023, IBM’s market cap was only ~$100 billion.

The stock has risen with the AI wave to ~$275 billion as of July 2025 and the company has finally switched to paying a ~$6 billion dividend instead of buying back more stock.

IBM’s buy-back folly shows what happens when a finite-growth company pretends there’s more gold in the mine. The cash would have served shareholders far better as dividends (or even better if they would have built their Watson Jeopardy playing AI into ChatGPT).

If you think you’re running Rung Ladderton’s ladder company, here’s the playbook:

When the gang finally unmasks Rung Ladderton, he snarls, “I could’ve made it work, if it weren’t for you meddling kids!” The truth is simpler: no amount of villainy, or venture accounting, turns a non-recurring product into a compounding engine.

Gold mine companies aren't "bad" businesses. They can be incredibly lucrative and strategically valuable. But they are fundamentally different to run than a quintessential software business. The key is self-awareness. Know what kind of company you are. Mine your gold, be smart about how the business can grow, and know when to distribute the spoils.

.png)

![Problem, 7 Libraries (on the GPU) [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/edgium.png)