Introduction

With democratic backsliding becoming serious concerns in many countries around the world, scholarly interest in this dangerous phenomenon has spiked in recent years1,2. A particular feature of democratic backsliding, is the delegitimization of critical voices from the opposing side. Specifically, dissent—the expression of disagreement with the (dominant) group’s norms, actions, or decisions3,4—appears to be extremely relevant and essential to the functioning of democratic societies, as drawing attention to alternative views and courses of action can facilitate reform and social change5,6,7. Accordingly, efforts to (re)legitimize critical voices in this context may be integral to attempts to protect democratic principles, but the issue has yet to be addressed from an intervention perspective within the vast literature on democratic erosion. Meanwhile, the delegitimization and exclusion of critical voices discourages constructive discourse, leading societies to become more oppressive and thus less democratic8. To safeguard democracy, it is therefore crucial that societies safeguard the freedom of expression and the right to criticize.

In different countries around the world, those who seek to defend democratic institutions and values have been delegitimized in public discourse9,10,11. Namely, civil actors and movements that strive to protect democracy and human rights have found themselves under attack for criticizing regimes and policies in countries like Brazil12, Poland13, Russia14, and Israel15. Even in Western democracies like the United States, critical voices are not always accepted. Planned Parenthood is a case in point: Despite offering several services that are broadly accepted by the public (e.g., the testing and treatment of sexually-transmitted infections), the organization suffers from widespread delegitimization over a subset of its activities, namely the highly-polarized topic of abortion16.

In this research, we examine whether and how the perceived legitimacy of critical voices can be increased in the Israeli context, where civil and political actors have been struggling to uphold democratic values in the face of widening polarization17,18 and an anti-democratic political agenda19. The New Israel Fund (NIF) is one of the most prominent civil actors to have taken on the role of defending Israeli democracy, and it has faced delegitimization as a result. This organization represents many critical voices, especially from the shrinking political left, which have in recent decades faced long and hard delegitimization campaigns from both the political leadership and NGOs and media outlets associated or aligned with it.

As a representative case of both the local and international protection of liberal democracy, we employ the case of the NIF, a high-profile and widely delegitimized umbrella NGO. We conducted this research in collaboration with the aChord Center, an applied research center in Israel, and the NIF. The latter organization funds a multitude of other local organizations working to promote equality, minority rights, fair social services and other fundaments of liberal democracy, as well as organizations promoting an end to Israel’s occupation of Palestine—a position more associated with the Israeli Left. Through these activities, the NGO raises and amplifies voices that are critical of the Israeli government, its policies, and the activities of some of the country’s sacred institutions (e.g., the Israeli army).

Meanwhile, public intolerance of internal criticism has increased alongside the violent escalation in the Israel-Palestinian conflict20, and efforts meant to weaken and delegitimize peace-advocating and left-wing civil society actors in Israel have become more prominent and successful in recent years21,22. Delegitimization campaigns directed at the NIF, labeling its employees as “traitors,” “foreign agents,” and “enemies of the state”22, have focused on the NGO’s support of organizations that publicly document, criticize, and strive to end Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The delegitimization the organization has endured is prototypical for how other critical civil society organization have been treated in Israel and how critical voices are generally delegitimized and often silenced in the context of democratic erosion. Given the crucial role they play in upholding democracy, it is essential to ask: what intergroup psychological interventions might contribute to the public (re)legitimization of critical voices, allowing them to be heard across polarized divides?

To answer our research question, we start by considering the delegitimization process and its psychological underpinnings, rooted in social identification and categorization. The delegitimization process is essentially a process of social categorization, which can take many forms. Specifically, it is the “categorization of groups into extreme negative social categories which are excluded from human groups that are considered as acting within the limits of acceptable norms and/or values”23 (p. 170), and is particularly salient in highly-polarized (e.g., the U.S24.) and conflict-ridden (e.g., Israel25) societies. It inherently follows an “us vs. them” mentality26, and may lead to harmful outcomes, such as conspiracy theories27, self-censorship7, endorsement of non-compromising attitudes, and participation in political violence28.

Notably, whereas delegitimization shares some of the same characteristics with dehumanization29,30, it is a separate phenomenon in that does not necessarily involve likening the group in question to animals, or seeing them as less-than-human. A normative concept in principle, delegitimization is reinforced by societal norms of what and who is appropriate in which context23. Political leaders and the media often encourage public endorsement of delegitimization by depicting critical voices as threatening31. Threat perceptions, in turn, amplify negative attitudes towards the group identified with the threat32,33, and a common reaction to an internal threat is to expel or exclude its source from the group in order to ensure cohesion26.

According to Social Identity Theory (SIT), individuals tend to categorize themselves and others into groups, identify with their own group as part of their self-concept and compare and prefer their group over others34. In this sense, delegitimization of critical voices follows a psychological pattern similar to other forms of political animosity and prejudice: the mere categorization of people into political ingroups and outgroups provides an incentive to discriminate34,35,36. Additionally, any case of ingroup criticism can threaten cohesion and the validity of ingroup norms and induce social identity threat3,25, especially in the presence of external threat37.

By portraying critical voices as separate from and threatening to the group’s status, safety, or even survival, anti-democratic regimes and their supporting structures (e.g., media, government-allied NGOs) create a hostile environment for critical voices, distancing them from the common ingroup identity and presenting them as malicious. In practice, the delegitimization of actors from the ingroup often comprises accusations of disloyalty and serving foreign interests (i.e., by receiving support from international organizations or other countries9,38,39). It is the “othering” of a group, its portrayal as foreign and unfamiliar, that enables its delegitimization.

But can this process be reversed? Paraphrasing Kelman, the process of legitimization refers to the recategorization of a target from illegitimate to legitimate. The ultimate legitimization outcome is therefore the acceptance and perception of a political actor (a system, group or person) as morally acceptable40. Per the relevant literature, we considered two broad approaches to the relegitimization of critical voices.

To address this, interventions based on a social (re)categorization approach, involving highlighting commonalities between the critical voices and the general public (i.e., the mainstream), can either change the perception of groups within an existing common boundary41,42,43 or attempt to recategorize entirely by emphasizing the role of a common superordinate identity, as suggested by the Common Ingroup Identity Model44,45. Following this logic, we developed three categorization-based interventions that we hypothesized would increase the perceived legitimacy of the delegitimized group: (1) highlighting mainstream activities (i.e., activities broadly-accepted within the public consensus) by the delegitimized target, thus highlighting common grounds; (2) constructing a common identity based on a value-based recategorization; and (3) presenting within-group disagreement as strengthening the common ingroup.

A second approach, based on the moralizing and value-oriented nature of legitimization processes, focuses on highlighting the inconsistencies between the delegitimizing attitudes individuals hold and their core values. At its core, the delegitimization of a group might be inconsistent with individuals’ held values and beliefs. This approach assumes that the natural desire for consistency46,47 will lead individuals—who often unknowingly deviate in their attitudes from their core values—to reconsider conflicting attitudes when the discrepancies are highlighted. Interventions revealing such inconsistencies have previously been found effective in reducing support for undemocratic practices48 and prejudice41,49.

This approach can be implemented using several techniques41. First, paradoxical thinking interventions confront individuals with an exaggerated representation of their held attitudes, which—when successful—leads to a sense of identity threat stemming from the inconsistency between this representation and one’s self-image50. Analogy-based interventions, on the other hand, can reveal inconsistencies between attitudes and core values through the presentation of similar cases from different contexts51,52. Finally, interventions applying proximal temporal framing of a potential future problem as more urgent53—for example, by presenting the group’s delegitimization as a slippery slope which is likely to harm democracy and conflict with one own’s preferences and desires—is another way in which an inconsistency between delegitimizing attitudes and core values can be brought to light. Consequently, we hypothesized that interventions employing (1) paradoxical thinking, (2) analogy, and (3) a presentation of the imminent threat of delegitimization to democracy could contribute to a group’s relegitimization.

Our main hypothesis, in accordance with common practice when conducting intervention tournaments49, is that each of the six interventions could increase the NGO’s Perceived Legitimacy relative to a control condition. Due to the polarized context and the NGO’s identification with the political left, we consider a potential interaction with ideology. Israeli leftists are more likely than other ideological groups to support the organization and view it as legitimate. In contrast to leftists, rightists in Israel are ideologically resistant to the NGO’s more controversial activities and are therefore more likely to see it as illegitimate and actively delegitimize it. Finally, centrists, a growing group in Israel with considerable political power, may be slightly more sympathetic to the organization than rightists, but are nonetheless affected in their attitudes by the mainstream delegitimized view of the NGO.

With this classification in mind, we treat legitimization as a holistic process. Unlike existing known delegitimization scales in the literature25,28,54, which mostly aimed to capture Jewish Israelis’ delegitimization of Palestinians, in this research, in the context of democratic backsliding, it was important for us to capture the legitimization of civil society and other critical voices, who share a common ingroup with the delegitimizing actor(s). Such societal legitimization might comprise different desired outcomes for different audiences: The first, which is the focus of this paper, addresses the need to increase legitimizing attitudes and behaviors towards the delegitimized group—i.e., the group’s perceived legitimacy—among those who view it more hostilely (i.e., mainly rightists and centrists). The second, outside the scope of this paper, is concerned with enhancing the active engagement (i.e., sense of identification and wish to act together) of those closer and more similar to the delegitimized group (in this case, political leftists).

Method

The study consisted of two waves of online surveys, with the second measurement taking place about 2 weeks after the first. The study was approved by the Hebrew University Ethics Committee. All analyses were conducted in R Version 4.3.0. All data was collected online and saved through the Qualtrics survey platform. T1 data was collected between December 10, 2020 and February 16, 2021. T2 data was collected from February 21, 2021-March 21, 2021 following pre-registrations on AsPredicted on February 19 and February 21, 2021 (see https://aspredicted.org/4rkp-sqgz.pdf & https://aspredicted.org/jsfz-nxgq.pdf). We obtained informed consent in the beginning of each survey, and participants were compensated for their participation by the survey company. All statistical tests were two-sided unless otherwise noted. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Although the study was pre-registered, several methodological adjustments were made during its execution. Below, we outline the key deviations from our original pre-registration.

Deviations from pre-registration

Several deviations from our pre-registered plan occurred due to practical and methodological considerations. First, the study was initially pre-registered as two separate studies (differed primarily by the specific interventions included in each) due to an unplanned expansion of intervention conditions. To ensure a robust baseline, we later merged the datasets and combined the two (identically-operationalized) control groups after confirming no significant baseline differences. Second, due to an oversight, our pre-registration stated that no data had been collected at pre-registration. Although hypotheses were formulated solely based on expected intervention effects at T2, which was collected post-registration, it would have been more accurate to say that some data (i.e., the baseline measurement, T1) has already been collected.

In terms of our hypotheses and DVs, our original hypotheses emphasized total of nine intervention effects on specific ideological groups, according to its relation to the outgroup in question and estimated ideological fit of the different interventions included in the project. However, as we decided to focus the paper on perceived legitimacy (rather than the other engagement factor, see more below), the main text zooms in on a subset of the six interventions that are relevant to the theoretical focus, with results pertaining to the other interventions included in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Table 7. Strong main effects across the full sample led us to focus on overall effects in the main text, with group-specific analyses vis-à-vis the pre-registered hypotheses also reported in Supplementary Note 2. Additionally, we pre-registered a three-component measure of legitimization but conducted an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to optimize item compatibility with our study’s unique legitimacy measure. The resulting two-factor structure (Perceived Legitimacy and Engagement) was adopted, while results using the pre-registered approach are reported in Supplementary Note 3.

The following deviations were made from the registered analysis: we used a linear mixed-effects model (lmer in R) instead of a traditional mixed within-between ANOVA to better account for repeated measures (T1 and T2) and the three-way interaction of time, condition, and ideology. Mixed-effects modeling provided greater statistical power and robustness to unbalanced data. In addition to our pre-registered exclusion criteria (failing attention checks), we excluded duplicate responses and participants who did not complete all DV items at both time points as including either would interfere with our intention to properly analyze the data. Three exploratory variables—Willingness to Act on Facebook, Perceived Threat and Support for Violence—were included in the main text due to their relevance to group legitimacy. Finally, we pre-registered an expected 20% dropout rate, estimating a final sample of ~1947 participants. However, the actual dropout rate was 30.5%, resulting in 1,691 responses at T2. Analyses comparing dropouts versus participants who completed both waves revealed no significant differences in baseline legitimization levels (t(1478.2) = −1.28, p = 0.200, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.04]) or ideological group identification (χ²(2) = 4.20, p = 0.122), suggesting attrition was not systematically related to key variables.

Participants and procedure

We reached out to participants online via an Israeli survey company (iPanel). As per our pre-registration, we removed participants who failed attention checks (n = 137 in T1). In addition, we excluded from analysis duplicate responses (n = 36 in T1) and participants who did not complete all DV items, either because they were screened in the beginning of the survey based on demographic information or dropped out (n = 891 in T1). In Wave 1, we recruited 2433 Jewish Israelis (Mage = 45.6, SDage = 15.8, range: 18–86). Of them, 52% self-identified as men (n = 1266), 48% as women (n = 1167), and none chose the option “prefer not to say”. In terms of political ideology, 30% of participants self-identified as rightists (n = 742), 31% as centrists (n = 749), and 39% leftists (n = 942). We intentionally recruited large-enough sub-samples of participants who identify with Israel’s three main ideological groups to allow for the proposed moderation analysis. They were invited to take part in a study on social and political issues. They completed informed consent followed by a short demographics questionnaire followed by number of measures regarding different political groups and organizations (for the full list of measures, see Supplementary Methods; measures relevant to our study are reported below).

We invited all participants from the first wave (T1) to participate in the intervention tournament in the second wave (T2), reaching a total of 1691 participants (the 1220 exposed to the relevant interventions were included in the analysis presented in the paper). As per our pre-registration, we removed participants who failed attention and reading checks (n = 251 in T2). In addition, we excluded from analysis duplicate responses (n = 85 in T2) and participants who did not complete all DV items, i.e., dropped out early (n = 138 in T2). Participants were invited to participate in another study on social and political issues. The sample was also representative in terms of age and gender (Mage = 44.9, SDage = 15.3, range: 18–86). Of them, 52% self-identified as men (n = 873), 48% as women (n = 818), and none chose the option “prefer not to say”. In terms of political ideology, 30% of participants self-identified as rightists (n = 508), 30% as centrists (n = 506), and 40% leftists (n = 677) (see Supplementary Table 1 for a summary of demographic characteristics, and Supplementary Table 2 for demographics per condition).

After completing informed consent and an attention check, participants were assigned to conditions through block randomization (based on their political ideology—right, center, or left—and baseline perceived legitimacy level, resulting in a total of 12 blocks) to one of the conditions and responded to the same outcome measure as well as other exploratory items (see Supplementary Methods). They were informed that they would be presented with a recent post from the NGO’s Facebook page and then asked to respond to questions about it. Following the exposure to one of the conditions, they responded to a few questions about the post (e.g., “how would you react if you saw the post on Facebook?”), the main outcome variables and some exploratory measures.

A sensitivity analysis using R for a between-subjects design with 7 independent conditions, a sample size of 1220, an alpha level of 0.05, and a desired power of 0.80, indicated that the study would have 80% power to detect an effect size as small as Cohen’s f = 0.106, which corresponds to Cohen’s d = 0.213. Of individuals who entered the survey in T1, 3% did not agree to participate and another 8% dropped out while filling out the survey. Of individuals who entered the survey in T2, 1% did not agree to participate and another 7% dropped out while filling out the survey.

Construction of the perceived legitimacy measure

For the perceived legitimacy outcome, we opted to use a self-created measure, as existing scales did not fully capture our intended construct. Prior delegitimization measures25,28,54, which were constructed in the context of Jewish-Palestinian relations and the Ethos of Conflict54, did not adequately address the political dimension of our research interest. Similarly, existing measures of political (in)tolerance55,56, while applicable in political contexts, did not sufficiently capture the normative element of legitimacy, specifically when referring to an NGO.

We synthesized components from both types of measures. For instance, our item “In my opinion, people who [support the NGO] are traitors,” is in line with Hammack et al.’s28 delegitimization item “Most Palestinians support terrorism”, while our item “In my opinion, it is appropriate for artists and public figures to participate in events organized or supported by [NGO name]” resembles a reversed adaptation of Crawford’s56 political intolerance item “I think that this group should not be allowed to organize in order to influence public policy.” Maintaining the theoretical conceptualization of delegitimization as a process of social categorization, we included items considering ingroup membership (e.g., “In my opinion, it is appropriate for organizations to receive financial support from [NGO name]”). Additionally, we incorporated context-inspired items such “In my opinion, [NGO name] is a legitimate body” and “I would boycott an event organized by [NGO name]”.

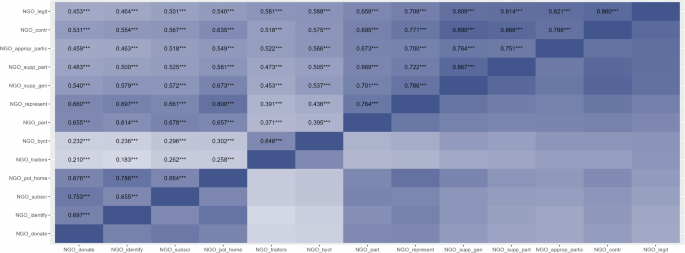

To identify the underlying factors behind the outcome measure composed of legitimizing and delegitimizing perceptions and sentiments regarding the NGO, we conducted EFA. In T1, we included 16 self-report items tapping into perceived legitimacy, beliefs, attitudes, desired behavior, and identification regarding the NGO, all rated on a 1 (not at all)—6 (to a great extent) scale. We retained 13 items in T2, removing three that we deemed repetitive or less relevant (see more information in Supplementary Methods). The mean score of the 13-item scale in T1 was 3.00 (SD = 1.2), just below the midpoint (α = 0.95). First, we evaluated the correlations between the variables and confirmed that none were too highly correlated (r > 0.90) (Fig. 1). A Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (Overall MSA = 0.94) and Bartlett’s test for sphericity (χ² = 31532.99, df = 78, p < 0.001) confirmed that the items were sufficiently correlated to perform factor analysis57,58.

The heatmap displays Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between all study variables for the full T1 sample (n = 2433). Positive correlations are shown in blue colors, and negative correlations in reddish-orange colors. The intensity of the color indicates the strength of the correlation, with darker colors representing stronger relationships. White represents correlations near zero. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Correlation values are displayed in each cell with corresponding significance markers. Non-significant correlations are displayed in lighter shades. Variables are clustered hierarchically based on similarity of correlation patterns. This visualization uses a colorblind-friendly blue/reddish-orange diverging palette that maintains distinction for all types of color vision.

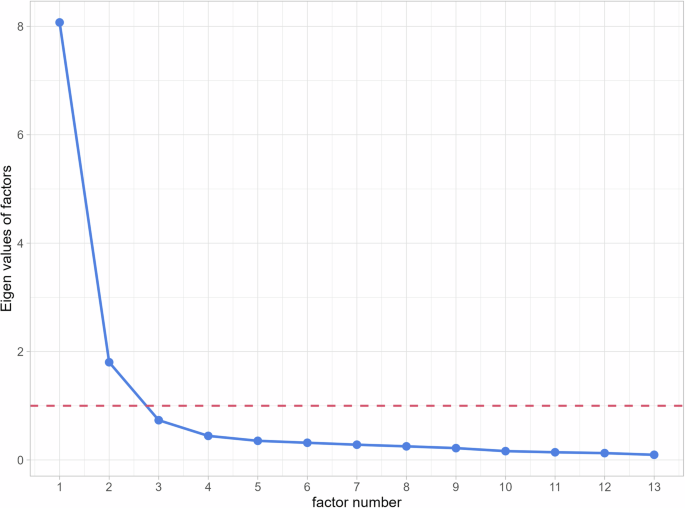

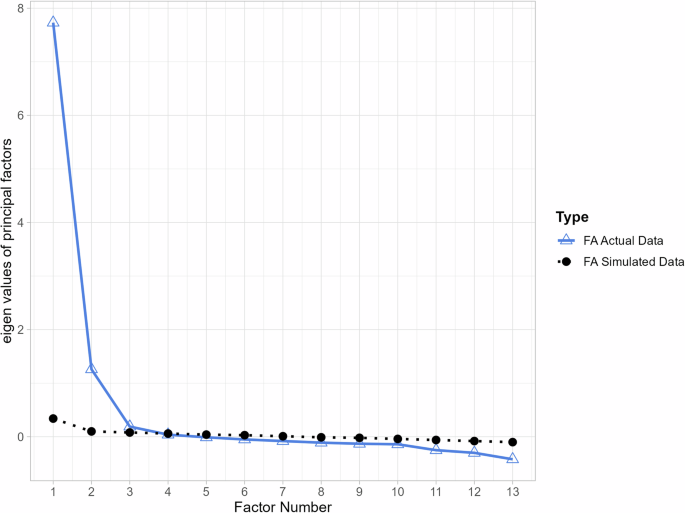

We performed both scree plot analysis and parallel analysis to determine the optimal number of factors. The scree plot indicated a clear 2-factor solution with a sharp drop after the first and second factors (eigenvalues: 8.07, 1.80, 0.73) (see Fig. 2), while parallel analysis suggested a possible 3-factor solution (see Fig. 3). We conducted EFA using principal axis factoring with quartimin rotation, as we anticipated the factors would be moderately correlated.

The scree plot displays eigenvalues (y-axis) for each factor (x-axis) extracted from the factor analysis. Factors are arranged in descending order of eigenvalue magnitude. The blue line with markers represents the eigenvalues, while the dashed red horizontal line indicates the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue = 1) commonly used for factor retention decisions. Based on this criterion, two factors were retained (eigenvalues > 1). This visualization uses a colorblind-friendly blue and red color scheme to ensure accessibility for all types of color vision.

The parallel analysis scree plot compares observed eigenvalues from factor analysis (blue solid line with triangles) with eigenvalues from simulated data (black dotted line with circles) across factors. Factors where the observed eigenvalue exceeds the simulated eigenvalue are considered significant and retained for further analysis. Based on this analysis, three factors were retained as suggested by the parallel analysis results (parallel analysis suggested number of factors = 3). The visualization uses a colorblind-friendly color scheme with distinct line styles and shapes to ensure accessibility for all types of color vision.

We compared 2-factor and 3-factor solutions and selected the 2-factor model based on theoretical interpretability, parsimony, and the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1). This solution, supported by eigenvalues of 7.82 and 1.44, explained 64.6% of variance, with factor loadings ranging from 0.36 to 0.87 (Factor 1) and 0.56 to 0.87 (Factor 2), and item communalities from 0.44 to 0.87. The two factors, which distinguish legitimacy judgments from engagement intentions, were moderately correlated. While the 3-factor solution explained slightly more variance (67.8%), the third factor’s eigenvalue (0.46) fell well below the conventional Kaiser criterion threshold of 1.0, and it added minimal explanatory power relative to the increased model complexity. Thus, the 2-factor solution offered a clearer, more parsimonious structure. For items that cross-loaded on both factors, we assigned them to the scale where they had the higher loading. We calculated composite scores for each factor by averaging the respective items. See Supplementary Table 3 for full factor loadings.

Eventually, the first factor comprised items that refer more directly to the perception of the NGO as politically legitimate (e.g., “In my opinion, the [NGO name] is a legitimate body,” “I would boycott an event organized by the [NGO name]” [reversed]). The second factor represented closer engagement with the group (e.g., “I feel that the [NGO name] represents me through its activities and the organizations it supports,” “I would consider taking part in an activity organized by the [NGO name]”).

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients in T1 for Factor 1, hereby referred to as Perceived Legitimacy, and Factor 2, hereby referred to as Engagement, were both 0.93 in T1, indicating excellent internal consistency. As expected, the two factors were moderately to strongly correlated (r(2431) = 0.68, 95% CI [0.66, 0.70], p < .001), supporting the use of an oblique rotation. We calculated composite scores for each factor by averaging the respective items.

Materials

In T1 participants filled out a long questionnaire with most items being used for exploratory and applied purposes by the NGO. Participants who returned in T2 completed a number of measures examining their reactions to the post and their perceived legitimacy levels, as well as some exploratory measures (for all measures see Supplementary Methods).

Unless otherwise noted, participants responded to all items on a 1 (“not at all”)—6 (“strongly agree”) scale. The following measures were included:

Demographics (T1)

Participants reported demographic information including their age, gender, religiosity, education, income level, and area of residence.

Political ideology (T1)

Political ideology was determined based on an ideological identification question ranging from 1 (extreme right) to 7 (extreme left). Political ideology can carry different meanings depending on the context59. In the highly affectively polarized context of our study, the self-defined categories of “left,” “right,” and “center” relate to the delegitimized group in different ways. Specifically, this self-categorization signals a specific orientation towards Palestinians in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories (with leftists more likely to support an end to the occupation and the peaceful resolution of the Israeli conflict and rightists more likely to view Palestinians as a security threat that needs to be controlled), which carries implications to their orientations towards groups that are critical of the state’s policies in this regard. We therefore treat political ideology as a categorical variable, coding participants who chose 1 (extreme right)—3 (moderate right) as rightists, those who chose 4 (center) as centrists, and those who chose 5 (moderate left) -7 (extreme left) as leftists.

Perceived legitimacy (T1–T2)

Following the results of the EFA, Perceived Legitimacy consisted of seven items (αT1 = 0.93; αT2 = 0.94), e.g.,: “In my opinion, the [NGO name] is a legitimate body”; “In my opinion, people who support the [NGO name] are traitors” (reversed item); “In my opinion, it is appropriate for artists and public figures to participate in events organized or supported by the [NGO name]”; “I would boycott an event organized by the [NGO name]” (reversed). We used T1 as a baseline measurement of the NGO’s Perceived Legitimacy. The full list of items appears in the Supplementary Methods.

Willingness to act on Facebook (T2)

The willingness to share the intervention post on one’s Facebook page was measured through one item: “to what extent would you be likely to share this post on your Facebook page?”

Perceived threat (T1–T2)

The perception of threat from the NGO was measured using two items that tap into threat on the symbolic (i.e., “The [NGO name] harms the values and identity of Israeli society”) and realistic levels (i.e., “The [NGO name] constitutes a real threat to the security of the state”). The items were strongly correlated at both T1 (r(2431) = 0.88, 95% CI [0.87, 0.89], p < 0.001) and T2 (r(1682) = 0.86, 95% CI [0.84, 0.87], p < 0.001). The T2 measure was used in a t-test as an exploratory outcome variable.

Support for violence (T1–T2)

Support for violence in its various forms was measures four items (i.e., “To what extent do you agree with the use of each of the following practices towards political opponents?”), including support of shaming, verbal abuse, vandalism and physical harm. The scale showed excellent internal consistency at both T1 (α = 0.94, 95% CI [0.93, 0.94]) and T2 (α = 0.90, 95% CI [0.89, 0.90]). The T2 measure was used in a t-test as an exploratory outcome variable.

Results

Preliminary survey results and intervention design

In the initial online survey (T1), we sampled 2433 Jewish Israelis, oversampling leftists at the expense of rightists to generate comparable and sufficiently large independent samples (Mage = 45.6, SDage = 15.8, range: 18–86; 52% men, 48% women; 30% rightists, 31% centrists, 39% leftists). Used as a baseline for the outcome variable, average Perceived Legitimacy level in T1 was 3.78 (SD = 1.36).

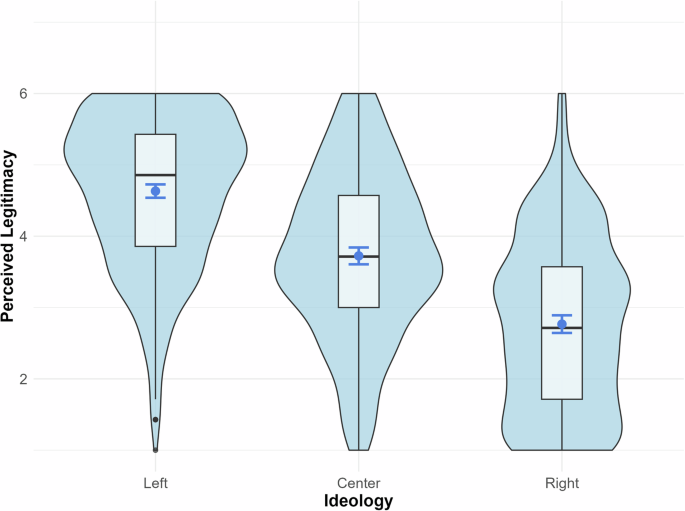

As expected, a one-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in T1 mean levels of Perceived Legitimacy among the three ideological groups (F(2, 2430) = 533.6, p < 0.001, ηp² = 0.31). Rightists averaged below the midpoint (M = 2.79, SD = 1.19), centrists slightly above it (M = 3.72, SD = 1.15), and leftists perceived the NGO as highly legitimate (M = 4.60, SD = 1.07). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated significant differences in Perceived Legitimacy levels across all ideological groups as follows: Leftists perceived the NGO as significantly more legitimate than centrists (mean difference = 0.88, 95% CI [0.75, 1.01], p < 0.001) and rightists (mean difference = 1.82, 95% CI [1.95, 1.69], p < 0.001). Centrists also viewed the NGO as more legitimate than rightists (mean difference = 0.94, 95% CI [1.07, 0.80], p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

This figure shows the relationship between political ideology (Left, Center, Right) and perceived legitimacy scores (scale 1–7). Violin plots (light blue) display the full distribution of scores for each ideological group. White boxplots within each violin show the median and interquartile range. Blue points represent group means with 95% confidence interval error bars. Sample sizes: Left (n = 942 participants), Center (n = 749 participants), Right (n = 742 participants). The visualization uses a colorblind-friendly color palette to ensure accessibility for all types of color vision.

After observing the T1 baseline, members of our research team along with aChord consultants and NIF employees designed the interventions for the intervention tournament. In line with the literature outlined above, six of the resulting interventions focused on manipulations of perceptions of commonalities and value inconsistencies. Three additional interventions, aimed at a different outcome of interest to the organization, are outside the scope of this paper (but see Supplementary Notes 1 and 3 for information regarding these interventions and the results of the analysis pertaining to them, respectively). Working on the interventions with the organization’s representatives enabled us to benefit from their practical knowledge and experience as a delegitimized actor and to incorporate messages they have considered or employed in past campaigns that fit into the above theoretical framework. We decided to use the organization’s own voice in the interventions and base the messages on true information pertaining to it, imitating a potential real-world application of the intervention (i.e., in its social media posts).

Accordingly, we formatted the interventions and the placebo Control to appear like screenshots of real Facebook posts on the NGO’s page. We chose Facebook as the target platform since it is widely used in Israel, both in general and in the context of polarized political discourse. Other than the text itself, which differed across conditions, we kept the design, length and style of the post (e.g., ending with a question) constant. As a Control, we used a real recent post on the NGO’s Facebook page that contained an administrative update, not addressing the organization’s activities or its delegitimization (images of the interventions are available in Supplementary Note 1). The interventions were designed to highlight commonalities (conditions 2-4) or value inconsistencies (conditions 5-7), per the literature reviewed above, and their content was as follows:

-

1.

Control condition (n = 332): A real post announcing the NGO’s move from WhatsApp to Signal as a communication platform.

Interventions highlighting commonalities:

-

2.

Highlighting Mainstream Activities (“Mainstream Activities,” n = 145): a post describing activities funded by the NGO that are within the Israeli consensus, including aiding populations hurt by the COVID-19 crisis, providing health services to marginalized communities, public housing, and more. Framed as an informative post, it provides information about elements of the NGO’s activities that have received less attention and are less controversial.

-

3.

Value-Based Recategorization (n = 147): a post presenting a recategorization of an ingroup and an outgroup based on shared values rather than declared political ideology, by providing examples of actions taken by populist right-wing leaders that would be considered extreme and inappropriate by most, and then asking readers to choose sides.

-

4.

Strengthening “Us” through Internal Disagreements (“Internal Disagreement,” n = 145): a post presenting disagreements as a healthy and caring part of everyday relationships, then applying the same idea to disagreements among societal and political groups, with the aim of normalizing the presence of diverse opinions within a common ingroup.

Interventions highlighting value inconsistencies:

-

5.

Paradoxical Thinking (n = 166): a post “justifying” the organization’s delegitimization and presenting the option of boycotting it as legitimate and rational, gradually proceeding to apply such boycott to more and more mainstream activities that the NGO has supported, like public transportation on weekends and aiding families from a low economic status, to the point of absurdity. Per previous findings on paradoxical thinking interventions, such an exposure to the absurd extreme is meant to surprise the reader, leading them to realize an inconsistency between their core beliefs and the attitude presented to them in a way that results in identity threat, which may in turn lead to them adjusting to more moderate attitudes50.

-

6.

Delegitimization Analogy (“Analogy,” n = 147): a post presenting an imaginary NGO in Brazil—as an external scenario—that engages in many societally-important activities (e.g., support marginalized native communities, promote equal opportunities in the workplace), but is nonetheless delegitimized and persecuted by state actors, much like the Israeli NGO. Focusing on an NGO’s delegitimization in a remote context allows for a more unbiased view, so as to encourage the reader to reconsider their context-specific held beliefs.

-

7.

Escalating Threat to Democracy (“Democratic Threat,” n = 139): a post presenting a potential gradual deterioration of Israeli democracy in the following years, as more and more groups and actions that are now considered acceptable lose legitimacy. The expected end outcome should reveal an inconsistency between one’s present attitude and future interests.

Intervention tournament

To test our main hypotheses, we employed an intervention tournament design53,54. We tested the effect of the interventions on Perceived Legitimacy among respondents allocated to one of the seven conditions using a linear mixed-effects model analysis (n = 1220 participants, repeated measures). Perceived legitimacy scores were analyzed using a three-way mixed-effects model with Condition (7 levels), Time (2 levels: Time 1, pre-intervention, and T2, post-intervention), and Political Ideology (3 levels: right, center, left) as fixed factors, and participant ID as a random factor.

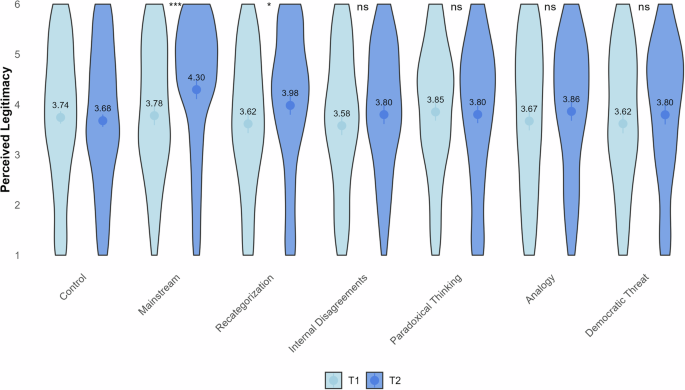

The two-way interaction between Condition and Time was significant, F(6, 1199) = 9.81, p < 0.001, ηp² = 0.05, indicating that the change in perceived legitimacy from pre- to post-intervention differed across conditions. To assess the effectiveness of each intervention relative to the control condition, we conducted post hoc planned contrasts at post-intervention (Time 2) with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons. As shown in Fig. 5, the planned contrasts revealed that the Mainstream Activities (M = 4.30, SE = 0.10, n = 151) and Value-Based Recategorization (M = 3.98, SE = 0.09, n = 147) interventions, both highlighting commonalities, were effective in increasing Perceived Legitimacy compared to the Control condition (M = 3.68, SE = 0.07, n = 331) in T2, with statistically significant differences (Mainstream: t(1213) = 4.85, p < 0.001, d = 0.48, 95% CI [0.29, 0.68]; Recategorization: t(1213) = 2.45, p = 0.044, d = 0.24, 95% CI [0.05, 0.44]).

The figure displays perceived legitimacy scores across different experimental conditions at two time points (T1: light blue, T2: dark blue). Violin plots show the distribution of scores, while points represent estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals (error bars). Numerical values above each point indicate the exact mean values. Significance indicators at the top compare each condition to the control condition at T2 (ns = not significant, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001). Sample sizes: Control: n = 331, Mainstream: n = 145, Recategorization: n = 147, Internal Disagreements: n = 145, Paradoxical Thinking: n = 166, Analogy: n = 147, Democratic Threat: n = 139 participants. This visualization uses a colorblind-friendly blue palette with two distinct shades to differentiate time points, ensuring accessibility for all types of color vision.

The remaining interventions showed non-significant differences from the Control condition: Internal Disagreements (M = 3.80, SE = 0.10, n = 145, t(1213) = 1.34, p = 0.218, d = 0.13, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.33]), Paradoxical Thinking (M = 3.80, SE = 0.09, n = 166, t(1213) = 0.86, p = 0.388, d = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.11, 0.27]), Analogy (M = 3.86, SE = 0.10, n = 147, t(1213) = 1.65, p = 0.199, d = 0.16, 95% CI [−0.03, 0.36]), and Democratic Threat (M = 3.80, SE = 0.10, n = 139, t(1213) = 1.38, p = 0.218, d = 0.14, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.34]). For a summary of the ANOVA and post-hoc comparisons, see Supplementary Tables 4–6.

Within-subject contrasts in Perceived Legitimacy revealed significant changes across interventions. The Mainstream intervention produced the largest effect, with a significant increase perceived legitimacy from pre- to post-intervention (estimate = 0.52, SE = 0.08, t(1199) = 6.72, p < 0.001, d = 0.81, 95% CI [0.57, 1.04]). Similarly, the Recategorization intervention showed a substantial increase (estimate = 0.37, SE = 0.08, t(1199) = 4.85, p < 0.001, d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.34, 0.80]). Moderate but statistically significant increases were also observed for the Internal Disagreements intervention (estimate = 0.22, SE = 0.08, t(1199) = 2.88, p = 0.004, d = 0.34, 95% CI [0.11, 0.58]), the Analogy intervention (estimate = 0.19, SE = 0.08, t(1199) = −2.53, p = 0.011, d = 0.30, 95% CI [0.07, 0.53]), and the Democratic Threat intervention (estimate = −0.18, SE = 0.08, t(1199) = 2.27, p = 0.023, d = 0.28, 95% CI [0.04, 0.51]). In contrast, neither the Control condition (estimate = 0.07, SE = 0.05, t(1199) = 1.30, p = 0.194, d = 0.10, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.25]), nor the Paradoxical Thinking intervention (estimate = 0.05, SE = 0.07, t(1199) = 0.73, p = .468, d = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.14, 0.30]), showed statistically significant changes from pre- to post-intervention.

The three-way interaction between Time, Condition and Ideology also had a significant effect on Perceived Legitimacy, F(12, 1199) = 2.03, p = 0.019, ηp² = 0.02. Post hoc analyses revealed that this three-way interaction was partially driven by the significant interaction effect of the Paradoxical Thinking intervention with Time and Ideology. Post hoc analyses revealed distinct patterns of intervention effectiveness across ideological groups. The Mainstream intervention showed significant effects compared to the Control condition at T2 across all ideological groups: centrists (estimate = 0.61, SE = 0.22, t(362) = 2.80, p = 0.032, d = 0.44, 95% CI [0.13, 0.75]), rightists (estimate = 0.81, SE = 0.24, t(358) = 3.40, p = 0.005, d = 0.53, 95% CI [0.22, 0.84]), and leftists (estimate = 0.44, SE = 0.16, t(479) = 2.84, p = 0.028, d = 0.36, 95% CI [0.11, 0.61]).

The Paradoxical Thinking intervention showed a unique pattern of ideological specificity. It had a marginally significant positive effect among centrists compared to the Control condition at T2 (estimate = 0.45, SE = 0.19, t(362) = 2.35, p = 0.058, d = 0.37, 95% CI [0.06, 0.68]), no significant effect among leftists (estimate = 0.05, SE = 0.16, t(479) = 0.30, p = 0.762, d = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.21, 0.29]), and a non-significant negative effect among rightists (estimate = −0.12, SE = 0.23, t(358) = −0.55, p = 0.874, d = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.39, 0.22]).

Additionally, examining within-subject changes revealed that the Paradoxical Thinking intervention had a non-significant positive effect from T1 to T2 among centrists (estimate = −0.18, SE = 0.12, t(1199) = −1.45, p = 0.147, d = 0.19, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.46]), no significant change among leftists (estimate = −0.03, SE = 0.12, t(1199) = −0.27, p = 0.790, d = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.22, 0.29]), and a significant decrease in perceived legitimacy among rightists (estimate = 0.36, SE = 0.13, t(1199) = 2.84, p = 0.005, d = 0.40, 95% CI [0.12, 0.67]). This distinctive pattern of ideological specificity was unique to the Paradoxical Thinking intervention, making it the only intervention that showed effectiveness that varied systematically by political ideology.

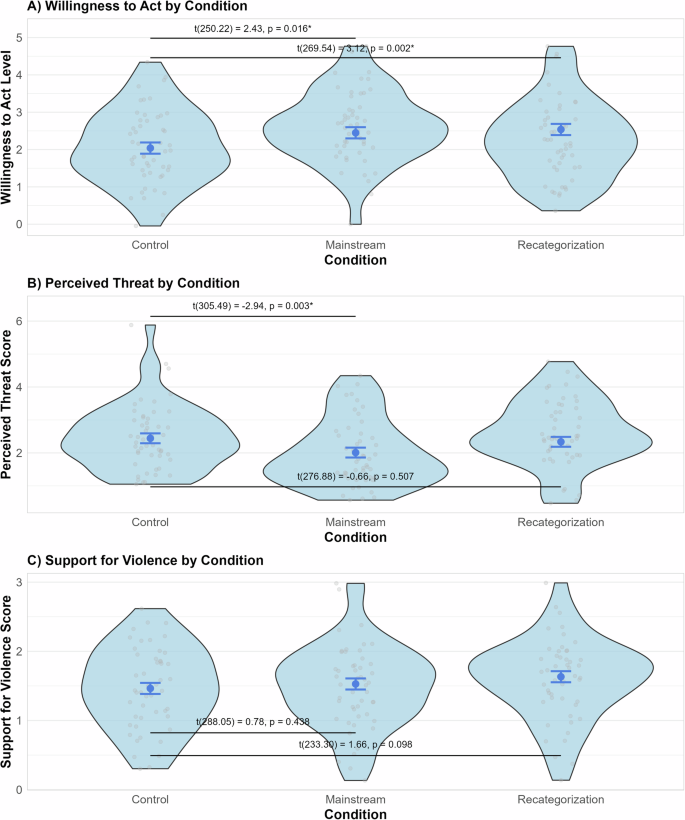

Exploratory analysis

As exploratory analyses, we tested the two effective interventions’ effects on behavioral intentions (i.e., the intention to share the post on Facebook), as well as variables associated with ideology-based delegitimization and polarization, namely: perceived threat and support for political violence. As seen in Fig. 6, two-sided t-test analyses revealed that participants in the Highlighting Mainstream Activity (t(250.22) = 2.43, p = 0.016, d = 0.25, 95% CI [0.06, 0.45]) and Value-Based Recategorization (t(269.54) = 3.12, p = 0.002, d = 0.31, 95% CI [0.12, 0.51]) conditions were significantly more likely to share the post on their Facebook page than participants in the control condition. Participants in the Highlighting Mainstream Activity condition also perceived the organization as less threatening (t(305.49) = −2.94, p = 0.003, d = −0.28, 95% CI [−0.48, −0.08]), but we found no statistically significant evidence that they were less or more likely to support acts of violence towards members of the opposing ideological group (t(287) = 0.78, p = 0.438, d = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.27]). These results add to the findings regarding the main outcome variables, which call attention to two interventions that highlight commonalities between the delegitimized group and the majority.

This figure presents the effects of experimental conditions (Control, Mainstream, and Recategorization) on three exploratory outcome variables: A Willingness to Act, B Perceived Threat, and C Support for Violence. Each panel displays the distribution of scores using light blue violin plots, with individual data points shown as gray dots. Blue circles represent group means with standard error bars. Statistical comparisons between Control and treatment conditions are shown with horizontal lines and annotations displaying t-test results (t-statistic, degrees of freedom, and p value). Significant results (p < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk. Sample sizes: Control (n = 331 participants), Mainstream (n = 145 participants), Recategorization (n = 147 participants). This visualization uses a colorblind-friendly color scheme to ensure accessibility for all types of color vision.

Discussion

The idea of recategorization interventions is grounded in psychological theory and backed by vast research addressing different types of commonalities. For example, Cehajic-Clancy et al.60. highlight the potential of highlighting morality-based commonalities, whereas Greenaway et al.61 focus on common humanity and Shnabel et al.62 examine common victim and perpetrator identities. Our interventions—and specifically the two effective interventions, Highlighting Mainstream Activities and Value-Based Recategorization—integrate insights from different realms and were found effective in an applied context.

While both interventions highlight commonalities between the mainstream and the delegitimized group, they do so in different ways. The Highlighting Mainstream Activities treatment touches on a number of areas that the NGO has invested in—namely, public health, public housing, anti-violence, anti-poverty—and relates to various common values and moral principles (e.g., moral principle of care, egalitarian values) and in so doing provided the audience with (previously unknown or unacknowledged) information (about the delegitimized group demonstrating its commonality with the mainstream). The Value-Based Recategorization treatment recategorized existing identities (namely, leftists, centrists, and rightists, or mainstream society vs. the critical voices at its margins) entirely, in favor of new value-based categories. In using perceived value-based commonalities—for example, in listing “believing in respecting others” and “believing in due legal process” as core values for the ingroup category—it creates new social categories that put the delegitimized group and much of the mainstream into the same category.

Taken together, our findings add to the literature on the value of highlighting commonalities while building on established theoretical foundations. Whereas the value of emphasizing shared interests and values is well-documented in SIT34 and the Common Ingroup Identity Model literature45 our research extends these frameworks in several ways. First, we demonstrate the distinct effectiveness of two different commonality-based approaches: highlighting superordinate ingroup interests and emphasizing shared values through recategorization. Second, we apply these established principles to a specific outcome—the relegitimization of critical voices within polarized environments—extending beyond traditional measures of prejudice reduction and intergroup relations. Most significantly, our comparative experimental design demonstrates that these commonality-based interventions not only effectively promote legitimization but outperform other established prejudice-reduction techniques that have proven successful in similar contexts. This comparative effectiveness validates the specific utility of commonality-highlighting approaches for addressing delegitimization, while acknowledging their theoretical roots in well-established social psychological principles.

Three other interventions—Internal Disagreement, Analogy, and Democratic Threat—appeared to also have an impact on Perceived Legitimacy, but only when compared to their own T1 Perceived Legitimacy values. That these interventions did not show an effect compared to the Control condition implies that they were less effective. Interestingly, the Paradoxical Thinking treatment, which did not affect Perceived Legitimacy overall, had an effect moderated by ideological groups, increasing Perceived Legitimacy only among centrists. The participants holding delegitimizing beliefs regarding the NGO were faced with a scenario of the delegitimization extending to the point of absurd, which prompted centrists, in comparison to rightists, to reconsider their attitudes. While Paradoxical Thinking is often more likely to affect individuals holding more extreme views, in this case it is likely the extreme delegitimization scenario exposed a real inconsistency for centrists but was not quite extreme enough to do so among rightists.

These findings have implications for understanding how to amplify critical voices and increase openness to them, as well as for the understanding of legitimization processes more generally. First, our findings demonstrate that even a highly delegitimized group can improve public opinion about their own legitimacy, using its own voice, and based on true information. Previous intervention research has mainly investigated how messages delivered by relatively objective or socially accepted actors can persuade public opinion, guided by an assumption that individuals resist information that contradicts their views about another group63,64, especially when the information comes from that group65,66. Our findings thus offer an important extension to past literature, demonstrating greater openness to receiving information directly from a delegitimized outgroup than was previously assumed rather than tested.

Offering a contribution to the literature on framing, our findings suggest that relegitimization processes, like delegitimization, are first-an-foremost framing processes. Oftentimes, real-world attempts at correcting misperceptions tackle these directly—an approach that may results in a “backfire effect”67, as engaging with a delegitimizing narrative may make it more salient and impactful. In contrast, our Highlighting Mainstream Activity, and to some extent all other interventions, do not debunk information but rather provide an alternative narrative on that information. By shedding light on mainstream activities, values, and identity, they provide a lens through which mainstream society can view critical voices without delegitimizing them.

Our findings can be understood within the multi-level nested framework of intergroup psychological interventions recently proposed by Čehajić-Clancy and Halperin68. While our interventions primarily targeted individual-level processes by modifying personal attitudes and beliefs, their effects demonstrate the interconnected nature of intervention levels. At the relational level, both the Value-Based Recategorization and Highlighting Mainstream Activities interventions restructured intergroup boundaries and fostered recognition of shared practices. The increased willingness to share these interventions on social media further suggests potential for broader societal impact through narrative change. This multi-level impact may help explain their comparative effectiveness against other established prejudice-reduction techniques.

From an applied perspective, the commonalities interventions could be easily adapted and used in the field, as delegitimized actors often also engage in activities and promote values that in isolation are considered acceptable or even desirable. Despite their differences, both the NIF and Planned Parenthood, as discussed in the introduction, constitute good examples of this, supporting in their work broadly accepted activities alongside activities on which views dramatically polarize. Highlighting the less controversial activities in these cases is relatively simple, and doing so in no way undermines the more challenging messages and activities promoted by these voices. That said, it should be acknowledged that intergroup delegitimization and power relations are often intertwined—specifically, a group that is delegitimized might hold less power, on either a material or a symbolic level, or at times both, than other groups in society. Our research and findings should not be interpreted as placing the responsibility for (re)legitimization on the delegitimized actor, but simply as detecting interventions that might increase their perceived legitimacy among a wide audience.

Limitations

The research has several limitations. First, to capture our outcome variable we employ a Perceived Legitimacy measure that had not previously been validated. We drew inspiration from existing measures and employed EFA to ensure internal validity, but future research should delve deeper into the psychological underpinnings of delegitimization and relegitimization processes in political contexts, in order to develop and rigorously validate more reliable measures.

Second, in an online study, the nature of the research design is not as controlled as that of lab studies. The information participants were given in the interventions competed with an endless stream of information in the outside world, often describing the same specific context or events. This can be seen as a limitation, but also a strength: first, the existing information, if anything, should have undermined our ability to demonstrate effects. This means that our test was a conservative one, and the fact that we still found positive effects of interventions increases our confidence in our findings.

As with other studies testing similar interventions63,69, we employ randomization of participants—meaning that pre-existing level and type of competing information should be relatively random—and compare all interventions to the same control condition—which should further increase comparability between the control and other conditions—to ensure the manipulation’s validity and increase its generalizability. Finally, whereas our study is not as controlled as studies conducted in lab settings, it is still controlled relative to studies conducted in the field. Yet, future research should aim to replicate the findings in other environments, including controlled lab settings and other contexts where critical voices are delegitimized, as well as in the field.

Finally, like much of the psychological intervention research conducted in recent years41, our research cannot determine whether any of the effective interventions can have lasting effects on perceived legitimacy. Due to the importance of measuring potential long-term impact, intervention durability should be taken into consideration in any future replication and extension attempts.

Conclusions

The delegitimization of critical voices that challenge the status quo poses a threat to democracy around the world. Here, we demonstrated through an intervention tournament how highlighting commonalities can contribute to the relegitimization of critical voices in the context of polarization and democratic backsliding. We used the case of an Israeli umbrella NGO that has suffered from long-lasting delegitimization. Similarly to other organizations in different places, it spotlights critical voices on contentious issues as part of the struggle to protect democracy. The interventions were all designed—together with the NGO at hand—to be readily implementable. To this end, we presented them as statements from the delegitimized actor itself rather than from more normative, mainstream actors from the ingroup—strengthening the importance of these findings as well as their applicability and potential value across different contexts where similar struggles for democracy take place. Practically, interventions highlighting commonalities can be implemented by nearly any delegitimized organization, however critical and polarizing. Accordingly, they carry the potential to decrease polarization and strengthen societies’ democratic foundations by increasing openness to and acceptance of delegitimized voices, contributing to the perceived legitimacy of critical voices that are too often the first victims of democratic erosion.

Data availability

The minimum data necessary to interpret, verify, and extend the findings of this research are available at: https://osf.io/8dcwt/.

Code availability

All code files for completing the analyses using R are available at: https://osf.io/8dcwt/.

References

Druckman, J. N. How to study democratic backsliding. Politi. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12942 (2023).

Braley, A., Lenz, G. S., Adjodah, D., Rahnama, H. & Pentland, A. Why voters who value democracy participate in democratic backsliding. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1282–1293 (2023).

Jetten, J. & Hornsey, M. J. Deviance and dissent in groups. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65, 461–485 (2014).

Hornsey, M. J. Dissent and deviance in intergroup contexts. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 11, 1–5 (2016).

Prislin, R. & Christensen, P. N. Social change in the aftermath of successful minority influence. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 16, 43–73 (2005).

Prislin, R. & Filson, J. Seeking conversion versus advocating tolerance in the pursuit of social change. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 97, 811–822 (2009).

Bar-Tal, D. Self-censorship as a socio-political-psychological phenomenon: conception and research. Political Psychol. 38, 37–65 (2017).

Morgan, J. & Kelly, N. J. Inequality, exclusion, and tolerance for political dissent in Latin America. Comp. Political Stud. 54, 2019–2051 (2021).

Wolff, J. The delegitimization of civil society organizations: thoughts on strategic responses to the “foreign agent” charge. in Rising to the Populist Challenge: A New Playbook for Human Rights Actors (eds. Rodríguez Garavito, C. & Gomez, K.) 129–137 (Dejusticia, 2018).

Müller, P. & Slominski, P. Shrinking the space for civil society: (De)Politicizing the obstruction of humanitarian NGOs in EU border management. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 4774–4792 (2022).

Chaudhry, S. The assault on civil society: explaining state crackdown on NGOs. Int. Organ. 76, 549–590 (2022).

Milhorance, C. Policy dismantling and democratic regression in Brazil under Bolsonaro: coalition politics, ideas, and underlying discourses. Rev. Policy Res. 39, 752–770 (2022).

Polynczuk-Alenius, K. “This attack is intended to destroy Poland”: bio-power, conspiratorial knowledge, and the 2020 Women’s Strike in Poland. Pop. Commun. 20, 222–235 (2022).

Malkova, P. Images and perceptions of human rights defenders in Russia: an examination of public opinion in the age of the ‘Foreign Agent’ Law. J. Hum. Rights 19, 201–219 (2020).

Gordon, N. Human rights as a security threat: lawfare and the campaign against human rights NGOs. Law Soc. Rev. 48, 311–344 (2014).

Freedman, Z. Political outcry skews perception of Planned Parenthood services. Daily Bruin https://dailybruin.com/2015/08/10/zoey-freedman-political-outcry-skews-perception-of-planned-parenthood-services (2015).

Orian Harel, T., Maoz, I. & Halperin, E. A conflict within a conflict: intragroup ideological polarization and intergroup intractable conflict. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 34, 52–57 (2020).

Gidron, N., Sheffer, L. & Mor, G. The Israel polarization panel dataset, 2019–2021. Elect. Stud. 80, 102512 (2022).

Gidron, N. Why Israeli democracy is in crisis. J. Democr. 34, 33–45 (2023).

Shamir, M. & Sagiv-Schifter, T. Conflict, identity, and tolerance: Israel in the Al-Aqsa Intifada. Political Psychol. 27, 569–595 (2006).

Sher, G., Sternberg, N. & Ben-Kalifa, M. The delegitimization of peace advocates in Israeli society. Strateg. Assess. 22, 29–41 (2019).

Katz, H. & Gidron, B. Encroachment and reaction of civil society in non-liberal democracies: the case of Israel and the New Israel Fund. Nonprofit Policy Forum 13, 229–250 (2022).

Bar-Tal, D. Delegitimization: the extreme case of stereotyping and prejudice. in Stereotyping and Prejudice: Changing Conceptions (eds. Bar-Tal, D., Graumann, C. F., Kruglanski, A. W. & Stroebe, W.) 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3582-8_8 (Springer, New York, NY, 1989).

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N. & Westwood, S. J. The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146 (2019).

Halperin, E., Bar-Tal, D., Nets-Zehngut, R. & Drori, E. Emotions in conflict: correlates of fear and hope in the Israeli-Jewish society. Peace Confl.: J. Peace Psychol. 14, 233–258 (2008).

Greenaway, K. H. & Cruwys, T. The source model of group threat: responding to internal and external threats. Am. Psychol. 74, 218–231 (2019).

Imhoff, R. et al. Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 392–403 (2022).

Hammack, P. L., Pilecki, A., Caspi, N. & Strauss, A. A. Prevalence and correlates of delegitimization among Jewish Israeli adolescents. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 17, 151–178 (2011).

Kteily, N. S. & Landry, A. P. Dehumanization: trends, insights, and challenges. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 222–240 (2022).

Tileagă, C. Ideologies of moral exclusion: a critical discursive reframing of depersonalization, delegitimization and dehumanization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 46, 717–737 (2007).

Tankard, M. E. & Paluck, E. L. Norm perception as a vehicle for social change. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 10, 181–211 (2016).

Stephan, W. G. & Stephan, C. W. An integrated threat theory of prejudice. in Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination (ed. Oskamp, S.) 23–45 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2000).

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O. & Rios, K. Intergroup threat theory. in Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination (ed. Nelson, T. D.) (Psychology Press, 2015).

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (eds. Austin, W. G. & Worchel, S.) 33–47 (Brooks/Cole, Monterey, CA, 1979).

Park, B. & Rothbart, M. Perception of out-group homogeneity and levels of social categorization: memory for the subordinate attributes of in-group and out-group members. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 42, 1051–1068 (1982).

Hartman, R. et al. Interventions to reduce partisan animosity. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1194–1205 (2022).

Adelman, L. & Dasgupta, N. Effect of threat and social identity on reactions to ingroup criticism: defensiveness, openness, and a remedy. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45, 740–753 (2019).

Brechenmacher, S. & Carothers, T. Defending Civic Space: Is the International Community Stuck? http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep20981.1 (2019).

Poppe, A. E. & Wolff, J. The contested spaces of civil society in a plural world: norm contestation in the debate about restrictions on international civil society support. Contemp. Polit. 23, 469–488 (2017).

Kelman, H. C. Reflections on social and psychological processes of legitimization and delegitimization. in The Psychology of Legitimacy: Emerging Perspectives on Ideology, Justice, and Intergroup Relations (eds. Jost, J. T. & Major, B.) (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Paluck, E. L., Porat, R., Clark, C. S. & Green, D. P. Prejudice reduction: progress and challenges. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 72, 533–560 (2021).

Brauer, M. & Er-rafiy, A. Increasing perceived variability reduces prejudice and discrimination. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 871–881 (2011).

Johnson, D. R., Jasper, D. M., Griffin, S. & Huffman, B. L. Reading narrative fiction reduces arab-muslim prejudice and offers a safe haven from intergroup anxiety. Soc. Cogn. 31, 578–598 (2013).

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L. & Saguy, T. Another view of “we”: majority and minority group perspectives on a common ingroup identity. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 18, 296–330 (2007).

Gaertner, S. L. & Dovidio, J. F. Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model (Psychology Press, 2014).

Festinger, L. Cognitive Dissonance. Sci. Am. 207, 93–102 (1962).

Aronson, E. Dissonance theory: progress and problems. in Theories of Cognitive Consistency: A Sourcebook 5–27 (Chicago, Rand-McNally, 1968).

Voelkel, J. G. et al. Interventions reducing affective polarization do not necessarily improve anti-democratic attitudes. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 55–64 (2022).

Bruneau, E., Kteily, N. & Falk, E. Interventions highlighting hypocrisy reduce collective blame of Muslims for individual acts of violence and assuage anti-Muslim hostility. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 430–448 (2018).

Hameiri, B., Nabet, E., Bar-Tal, D. & Halperin, E. Paradoxical thinking as a conflict-resolution intervention: comparison to alternative interventions and examination of psychological mechanisms. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 122–139 (2018).

Barak-Corren, N., Tsay, C.-J., Cushman, F. & Bazerman, M. H. If you’re going to do wrong, at least do it right: considering two moral dilemmas at the same time promotes moral consistency. Manag. Sci. 64, 1528–1540 (2018).

Shulman, D., Halperin, E., Kessler, T., Schori-Eyal, N. & Reifen Tagar, M. Exposure to analogous harmdoing increases acknowledgment of ingroup transgressions in intergroup conflicts. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 1649–1664 (2020).

Kim, J. Gain-loss framing and social distancing: temporal framing’s role as an emotion intensifier. Health Commun. 38, 2326–2335 (2023).

Bar-Tal, D., Sharvit, K., Halperin, E. & Zafran, A. Ethos of conflict: the concept and its measurement. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 18, 40–61 (2012).

Sullivan, J. L., Piereson, J. & Marcus, G. E. Political Tolerance and American Democracy. (University of Chicago Press, 1982).

Crawford, J. T. Ideological symmetries and asymmetries in political intolerance and prejudice toward political activist groups. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 55, 284–298 (2014).

Rasheed, F. A. & Abadi, M. F. Impact of service quality, trust and perceived value on customer loyalty in Malaysia services industries. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 164, 298–304 (2014).

Murphy, P. Exploratory factor analysis. RPubs https://rpubs.com/pjmurphy/758265 (2021).

Wojcik, A. D., Cislak, A. & Schmidt, P. The left is right’: left and right political orientation across Eastern and Western Europe. Soc. Sci. J. 0, 1–17 (2021).

Čehajić-Clancy, S., Janković, A., Opačin, N. & Bilewicz, M. The process of becoming ‘we’ in an intergroup conflict context: how enhancing intergroup moral similarities leads to common-ingroup identity. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 62, 1251–1270 (2023).

Greenaway, K. H., Quinn, E. A. & Louis, W. R. Appealing to common humanity increases forgiveness but reduces collective action among victims of historical atrocities. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 41, 569–573 (2011).

Shnabel, N., Halabi, S. & Noor, M. Overcoming competitive victimhood and facilitating forgiveness through re-categorization into a common victim or perpetrator identity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 867–877 (2013).

Bruneau, E., Casas, A., Hameiri, B. & Kteily, N. Exposure to a media intervention helps promote support for peace in Colombia. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 847–857 (2022).

Paolini, S. & McIntyre, K. Bad is stronger than good for stigmatized, but not admired outgroups: meta-analytical tests of intergroup valence asymmetry in individual-to-group generalization experiments. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 23, 3–47 (2019).

Maoz, I., Ward, A., Katz, M. & Ross, L. Reactive devaluation of an “Israeli” vs. “Palestinian” peace proposal. J. Confl. Resolut. 46, 515–546 (2002).

Greenaway, K. H., Wright, R. G., Willingham, J., Reynolds, K. J. & Haslam, S. A. Shared identity is key to effective communication. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 41, 171–182 (2015).

Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. When corrections fail: the persistence of political misperceptions. Polit. Behav. 32, 303–330 (2010).

Čehajić-Clancy, S. & Halperin, E. Advancing research and practice of psychological intergroup interventions. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 3, 574–588 (2024).

Banfield, J. C. & Dovidio, J. F. Whites’ perceptions of discrimination against Blacks: the influence of common identity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 833–841 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was initiated at aChord Center: Social Psychology for Social. We gratefully acknowledge the NIF for providing partial funding and collaborating with aChord on intervention design, and confirm it had no other role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. This work was also partially supported by a European Research Council grant (No. 864347) to the last author. We extend our sincere thanks to Chagai Weiss, Inbal Zipris, and Maayan Poleg for their valuable help with the overall research design and project management, as well as to Idan Gadot, Uri Zer Aviv and Mickey Gitzin for their helpful input during the intervention development process.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The following associations existed at the time of conducting this research: three of the authors—L.A., Y.H., and E.H.—were affiliated with aChord: Social Psychology for Social Change. E.H. is aChord’s Founder and Co-Director, and L.A. and Y.H. were employees of the organization. The NIF was aChord’s partner in the context of this project (i.e., providing partial funding and collaborating on intervention design). None of the authors have any formal association with the NIF, and the latter did not partake in the conceptualization, research design (other than interventions’ design), data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks Andrew McNeill and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jennifer Bellingtier. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aldar, L., Pliskin, R., Hasson, Y. et al. Intergroup psychological interventions highlighting commonalities can increase the perceived legitimacy of critical voices. Commun Psychol 3, 63 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00238-1

Received: 29 September 2023

Accepted: 19 March 2025

Published: 16 April 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00238-1

.png)