I don’t usually write deep dives explaining how tech works, but I had to make an exception for MiniDisc. Over the years, I’ve posted plenty about its design, its cult following, and how it fit into Sony’s story. But I kept running into the same thing: most people still don’t actually know how it worked. And honestly, it’s one of the coolest systems Sony ever built. So this time, I wanted to slow down, break it all down, and show why this misunderstood format deserves a second look.

MiniDisc is often remembered as a failed format, but that misses how far ahead of its time it really was. Long before streaming or solid-state MP3 players, Sony created a portable system that let you record, delete, edit, and organize music in real time. It used heated lasers, magnetic writing, smart compression, and skip-resistant memory, all packed into a compact cartridge. Once you see how it worked, the ambition becomes clear.

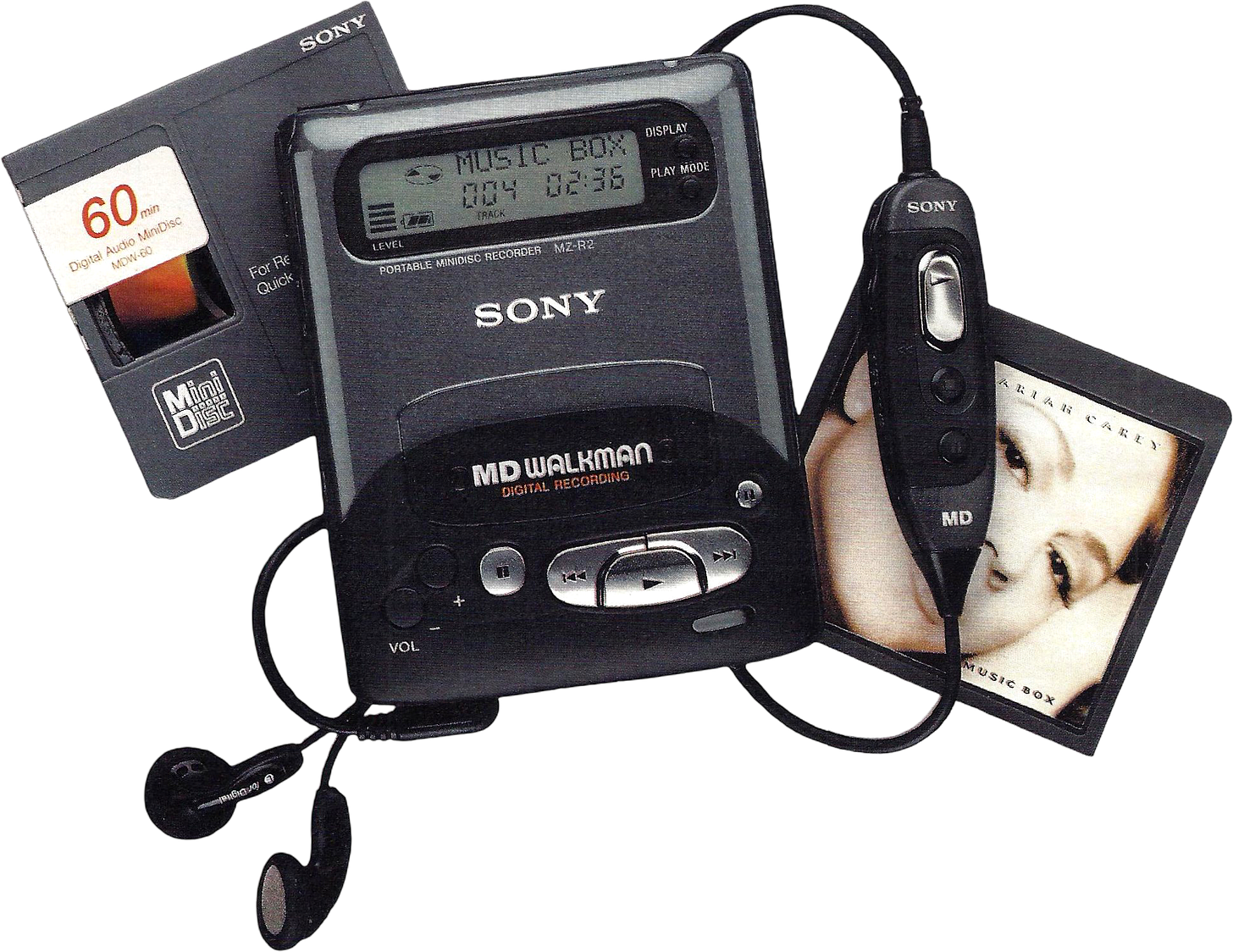

MD introduced three major innovations: rewritable magneto-optical discs, ATRAC audio compression to shrink file sizes, and a memory buffer that kept playback smooth even during movement. Each disc came in a tough plastic shell, combining cassette durability with the sound quality of a compact disc.

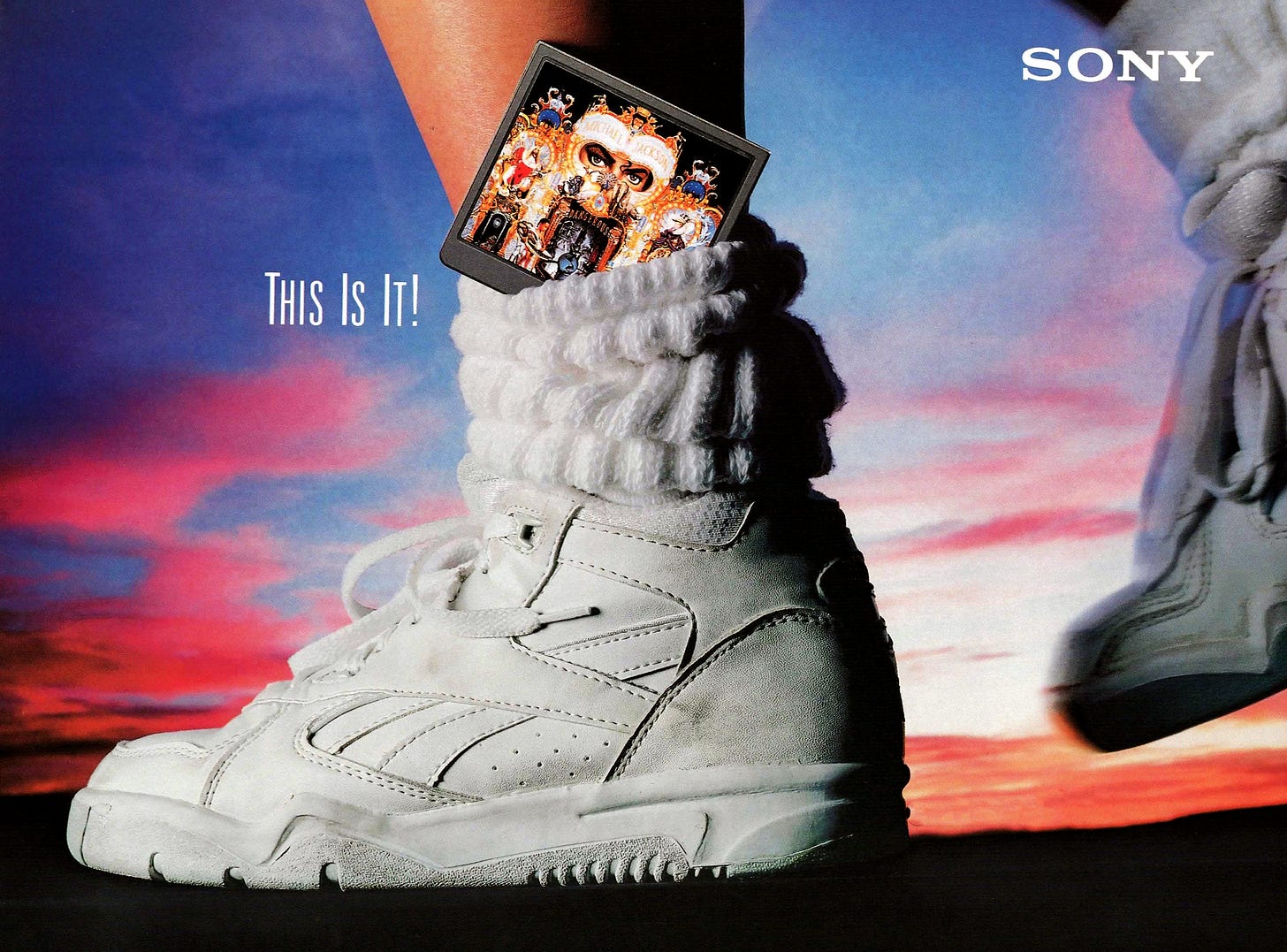

There were two types of discs. Rewritable ones for personal recording, and pre-recorded ones for commercial music. Sony licensed the format widely, hoping it would become a global standard. It succeeded in Japan, but elsewhere, CD-Rs and MP3 players quickly took over. Still, the technology behind MiniDisc was ahead of its time in almost every way.

At its core, MiniDisc used a unique recording system. A laser heated a pinpoint area on the disc to change its magnetic properties. At that exact moment, a magnet flipped the direction of that spot. Once cooled, the data stayed locked in as digital ones and zeroes.

The laser had two roles. During recording, it warmed the disc surface just enough to allow the magnet to write. The process didn’t require extreme accuracy, making it reliable even if the device was bumped. For playback, the laser operated at lower power. It read the magnetic data using the Kerr effect, where reflected light changes depending on magnetic orientation. That signal was converted back into audio.

CDs offered more storage, so to fit 74 minutes of music on a MiniDisc, Sony developed ATRAC—Adaptive TRansform Acoustic Coding. It compressed files down to about one-fifth their size while preserving quality.

ATRAC worked by dividing sound into frequency bands and removing audio the human ear couldn’t detect, like a faint sound hidden behind a louder one. This allowed for efficient compression without compromising fidelity.

The format was designed for real-time performance. Even early processors could handle ATRAC playback. Sony continued improving it over the years, releasing ATRAC3 and ATRAC3plus for better sound and longer recording times.

MiniDisc organized data like a small digital filing system. Each disc had a Table of Contents (TOC) that tracked where everything was saved. Instead of storing one large audio block, the player wrote in smaller chunks wherever there was space. The User TOC tracked each chunk’s order, location, and name.

This structure made editing seamless. You could move, rename, or delete tracks without affecting the rest of the disc. Deleted space was instantly reusable.

Audio was stored in clusters, each holding about two seconds of sound. These could be scattered across the disc, but during playback, the player reassembled them instantly. Edits like splitting or merging tracks changed only the TOC—not the audio data.

The hardware was equally advanced. When you inserted a disc, a sliding door inside the cartridge opened. A laser read from below, while a magnet hovered above. Some players used a mechanical arm to keep them aligned. The disc spun at a constant speed, and an advanced error correction system, adapted from CDs, helped prevent playback glitches.

To avoid skips, MiniDisc players included a small memory buffer that stored several seconds of audio in advance. If the laser was interrupted, music continued from memory. This made MiniDisc more dependable on the move than most early CD players.

Recording was fast and simple. You pressed record, the disc spun up, and the laser calibrated. Audio, whether digital or analog, was compressed with ATRAC and written in pieces across the disc. When you stopped recording, the TOC updated automatically.

Some units let you undo the last edit by saving the previous TOC. You could rename, move, split, or group tracks into folders.

In 2000, Sony introduced MiniDisc Long Play, or MDLP. It added two new recording modes: LP2, which doubled capacity to 160 minutes, and LP4, which stretched it to 320. LP2 kept decent quality. LP4 was more compressed and best for voice. These formats helped MiniDisc compete with MP3 CD players. Older units couldn’t read MDLP, so Sony labeled discs clearly and ensured new players supported both.

In 2001, NetMD brought high-speed PC transfers via USB and SonicStage software. Users could transfer music much faster than real-time, up to 32 times faster in LP4. But DRM restrictions prevented uploading recordings back to the computer. Even so, NetMD made MiniDisc feel like a modern format.

Sony’s biggest leap came in 2004 with Hi-MD. These new discs held up to 1 GB and supported uncompressed PCM recording. They could also reformat old blanks to hold more music, support ATRAC3plus, and act as USB drives for regular files. Later units added MP3 support, and the MZ-RH1 finally allowed full uploads back to a computer, making it a favorite among musicians and archivists.

But by then, flash memory had taken over. Hi-MD came too late. In 2013, Sony ended production of MiniDisc. There was no announcement. No celebration. Just the quiet retirement of a format that was years ahead of its time.

MiniDisc was Sony’s vision of the future, released into a world that wasn’t ready. Today, when we expect lossless audio, editable metadata, durable storage, and real-time control, it’s clear they had the right idea all along.

Made with Cotton Bureau, it’s high quality, water resistant, clean, and minimal. One-time drop. Get yours before it’s gone!

.png)