Updated November 11, 2025 02:27PM

There was a time that Strava was a well loved app, but lately it seems that the fitness app has traded user goodwill and gotten… well, nothing in return.

This all came to a head most recently this fall when Strava sued Garmin then quickly backed down. For now things look like they’ve stabilized, but but how did we get here?

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)Strava was a connector

The early days of Strava are also the early days of connected fitness devices and even the early days of our modern mobile phone ecosystem. When CyclingTips sat down with Strava’s co-founder and CEO, Michael Horvath in 2012, the team had 30 people at the office in San Francisco and considered launching a mobile app one of the biggest recent milestones.

Despite that milestone, you can sense the trepidation in Horvath’s tone. He seems to be looking to convince readers that a phone will do this new thing and, in discussing the app, he states “It’s an emerging platform and the future of ‘quantified self’. We can talk about how the form factor or battery life isn’t quite right…you certainly can’t swim with a phone, but in reality it’s how most folks are going to have their first experience capturing their data. It’s so easy to download the app and give it a try and get excited about what they see. Two thirds of our new users today are mobile users. It’s going to swamp the number of folks who are on Garmins.”

Now things did not actually work out quite like that. As it turns out Strava did not, as far as we know, dwarf Garmin users with mobile users. It does point to the state of the general ecosystem back then though. It was the wild west and no one was quite sure who might emerge as the largest providers of fitness data.

Consumers had lots of choices for big, and small, fitness sensors to capture data. Strava accepted all that data by being hardware agnostic and having an API that made it easy for small companies to use. One of the things that propelled Strava early on was that it was a data connector.

No matter what you used to capture your data you could funnel it to Strava. Once it was on Strava that same API allowed a bunch of other software companies to analyze it. All you had to do was get your data into Strava and it would follow you for years.

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)Strava also had leaderboards and matched rides

Back in those heady days you started getting your data in Strava because you knew it was secure but you also used Strava because of the competition. The most well known part of that competition was the segment leaderboards.

Even today when most people think of Strava they think of KOM or QOM competitions on big, or small segments. But that changed pretty quickly. Most people just aren’t that fast and as soon as the company gained traction it was impossible to compete for a lot of segments.

That left small scale or personal competition. You could compete with friends even if both of you weren’t near the top. Someone was faster and someone was slower and that’s a race. For those that weren’t interested in that, you could also compete against yourself by looking at your segment performance over time or you could compete against strangers by age group.

This isn’t really about competition though. Instead it’s about making the app sticky and getting people to come back. And it worked. Strava built a social network through fitness competition and built dedicated users ranging from hardcore athletes to techy types who wanted to try new hardware but keep track of their data. Those early adopters then rolled into casual users who enjoyed the community.

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

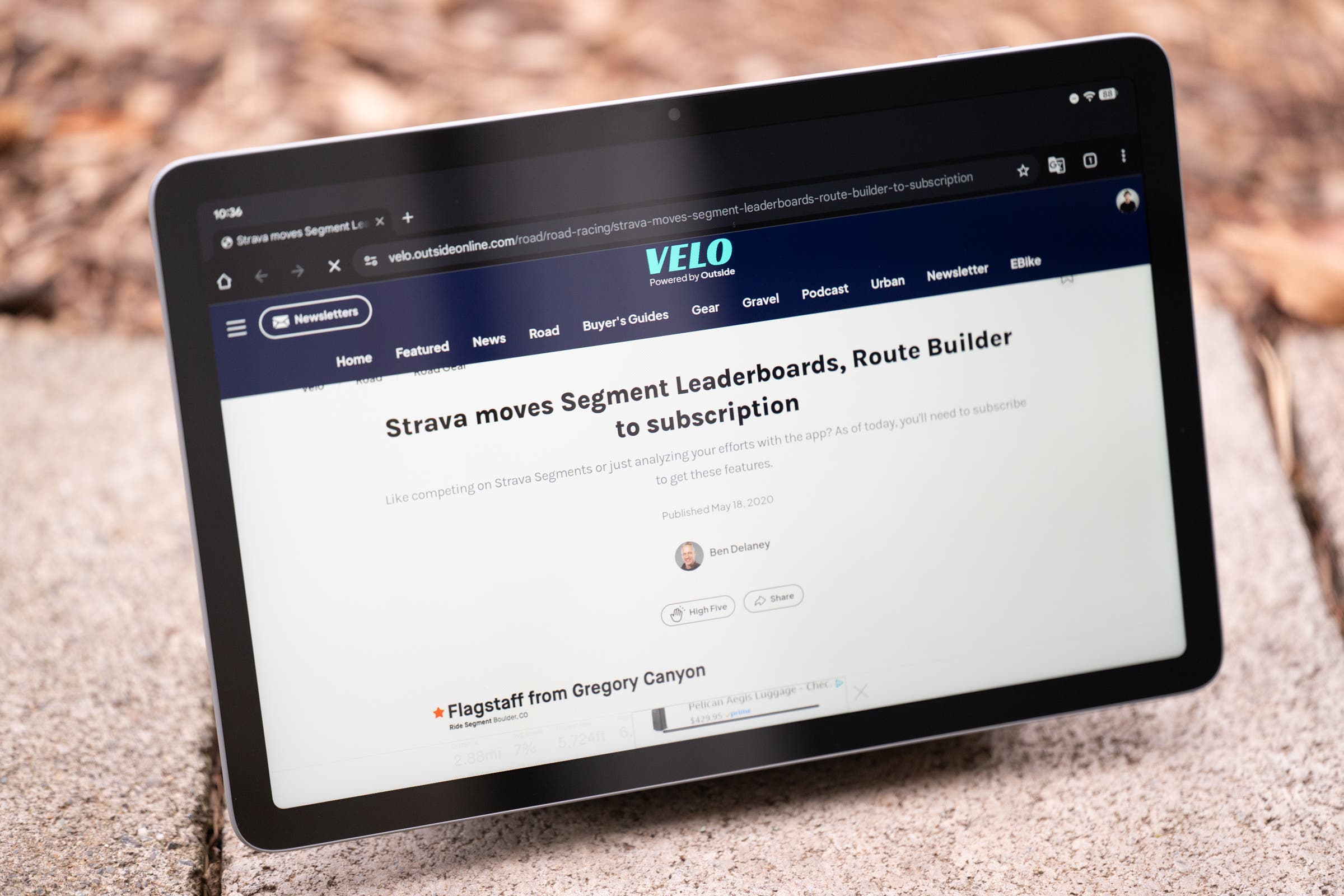

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)The first time Strava traded user goodwill was for subscriptions

Strava was formed in 2009 and like a lot of internet companies of that era turning the corner to profitability wasn’t easy. The goodwill of being a connector and offering competition and community was great for building a user base but that’s also great for setting cash on fire by the truckload.

The problem that existed for Strava was creating a compelling reason to convert from free to paid. The core components of why Strava mattered to people were free. So, obviously, the answer wasn’t to create a new reason to upgrade with compelling features but instead to take away those core components.

In early 2020 Ben Delaney wrote for Velo saying “segments are Strava’s differentiating feature. While many fitness trackers allow users to upload GPS files of their workouts, and offer various basic analytics, Strava has long had a competitive element where users are ranked by time on Segments, sections of road or trail demarcated by users. The Segment Leaderboards showcase every user’s time for each Segment, and can be broken down by gender, age, and weight. As of today, May 18, competing on Segments and analyzing them with Segment Leaderboards require a $5 monthly subscription.” He also went on to explain that “Other features being moved to subscription-only status include: Segment analysis, Training dashboard and training log, and Route Builder with Heatmap and Segment features.”

As you might expect, this did not win support for Strava business practices with users. It may have been a necessary step in Strava surviving, but no one was happy with it.

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)Next came a sudden API change

The problem for Strava with this change was that the environment of fitness tracking had drastically shifted between 2009 and 2020. The secret was out and getting a KOM in most major cities was impossible for most people. Taking that away wasn’t a big loss for people.

Acknowledging that fact, Strava also introduced Local Legends in 2020. Instead of needing to be the fastest, all you had to do was cover the same segment more than other users. It was also available to free users.

At the same time, the other features started to become widely available elsewhere. You couldn’t analyze your performance on a segment but you didn’t care because you weren’t trying for the segment KOM/QOM. You could still analyze your performance; it just required a third party app and there were lots of choices. Even route building with heatmaps was available from competitors.

Still, Strava had already done the work to build the community. You went to Strava because you wanted to give and get kudos from other users for your athletic activities. The app also continued to be a connector with an easy path for moving your data from a hardware device to Strava and from there to elsewhere.

That last bit was still a problem for Strava though. The API allowed third parties to take your data from Strava and analyze it. You still didn’t need to pay for Strava and by attempting to force users into a paid tier the company merely shifted how people used the platform.

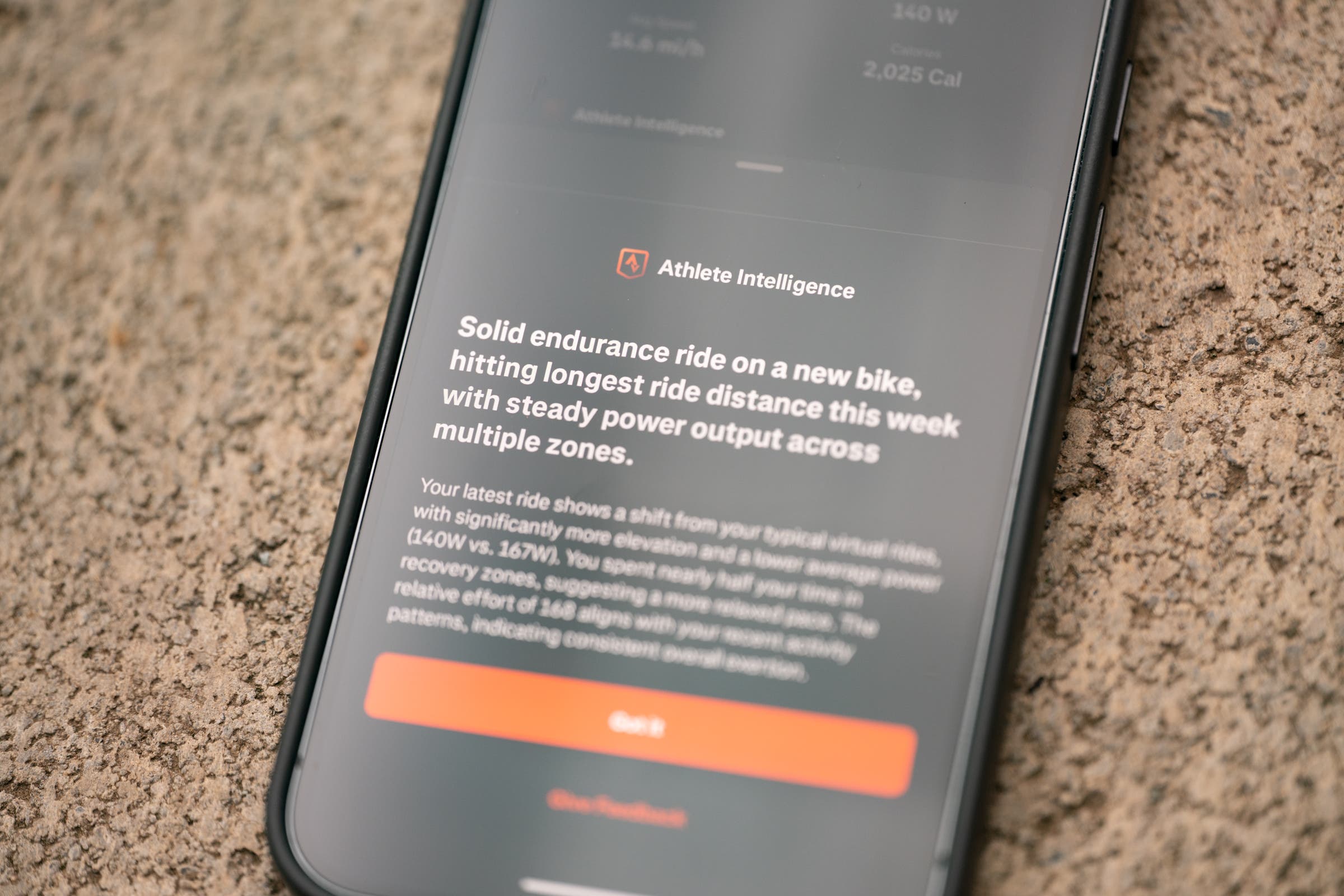

Then AI became a thing and Strava tried again to convert users. This time the company really did introduce new features.

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)In October of 2024, Strava introduced Athlete Intelligence as a “beta launch of an A.I.-powered feature ‘that provides personalized insights based on activity data.’” Or, more specifically, Strava promised “its Athlete Intelligence algorithms will cut through the clutter of cadence, heart rate, ‘relative effort,’ and whatever other metrics users obsess and become distressed over.”

That feature was a paid feature. The only problem was that users largely saw it as a complete waste of time and mocked it. If the plan was to convert users to paid, user sentiment leads me to believe it was not moving the needle. Also, Strava still had the issue of third party apps recreating Strava features and doing a better job. AI was merely the latest example of this issue.

In November of 2024, Strava closed that loophole with an email. The user-facing version stated “We’re reaching out to inform you of a change that affects how third-party apps connected to Strava may display certain information. This update, effective on November 11th, is part of our commitment to privacy and transparency across all connected apps and devices. Third-party apps will now only be allowed to display Strava activity data related to a specific user to that user. Partners will be required to update their app within 30 days of November 11th to align with this new standard.”

In other words, Strava shut down the entire app ecosystem that users loved. Strava was no longer a connector and instead became an end-point for data uploaded from other devices. The effect was to fundamentally change the landscape of fitness tracking, and the user response was not positive.

The change also had another, perhaps unexpected, result. Think back to the 2012 prediction that “Two thirds of our new users today are mobile users. It’s going to swamp the number of folks who are on Garmins.” Except, at least in the cycling space, that turned out to be laughable.

Instead, the phone as a device is actually shifting to less use and wearables are on the rise. Users are uploading from smart watches and bike computers, many of which come from Garmin. Garmin also has a fitness tracking system, called Garmin Connect, with many similar features as Strava, and there’s a plethora of third party apps that exist to analyze fitness data.

The combination of these factors has not pushed users to upgrade in droves because of a desire for Strava features. Instead, here at Velo and in reading user sentiment that’s shared, we’ve seen users shift away from Strava by creating direct connections between the data hardware and analysis systems such as Trainingpeaks or Xert.

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)Strava sued Garmin then quickly dropped the suit

During the API change, one of the things Strava claimed as reasoning was protection of user data. Basically it’s your data and Strava is just protecting it. This was framed as a response to AI model training with Strava saying “we believe the best decision for the platform and for users is to prohibit the use of data extracted from Strava users.” Except there is an inherent claim by Strava to that data given that Strava is still using it for AI purposes. Of course, Strava does say that “Privacy and user control are at the forefront of our platform. As a result, we are committed to evolving our API practices as regulatory requirements and user expectations shift.” That requires some trust though.

A lot of users also pointed out that the inherent claim to user data didn’t make a lot of sense. The data comes from a Garmin (or other manufacturer) device and users are asking for it to be used in particular ways that Strava is refusing.

We have no insight into the thinking on the part of Garmin here but it would seem Garmin also wanted to assert some ownership of the data that Strava was using. On July 1 of this year, “Garmin announced new developer guidelines for all of its API partners, including Strava, that required the Garmin logo to be present on every single activity post, screen, graph, image, sharing card etc.”

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

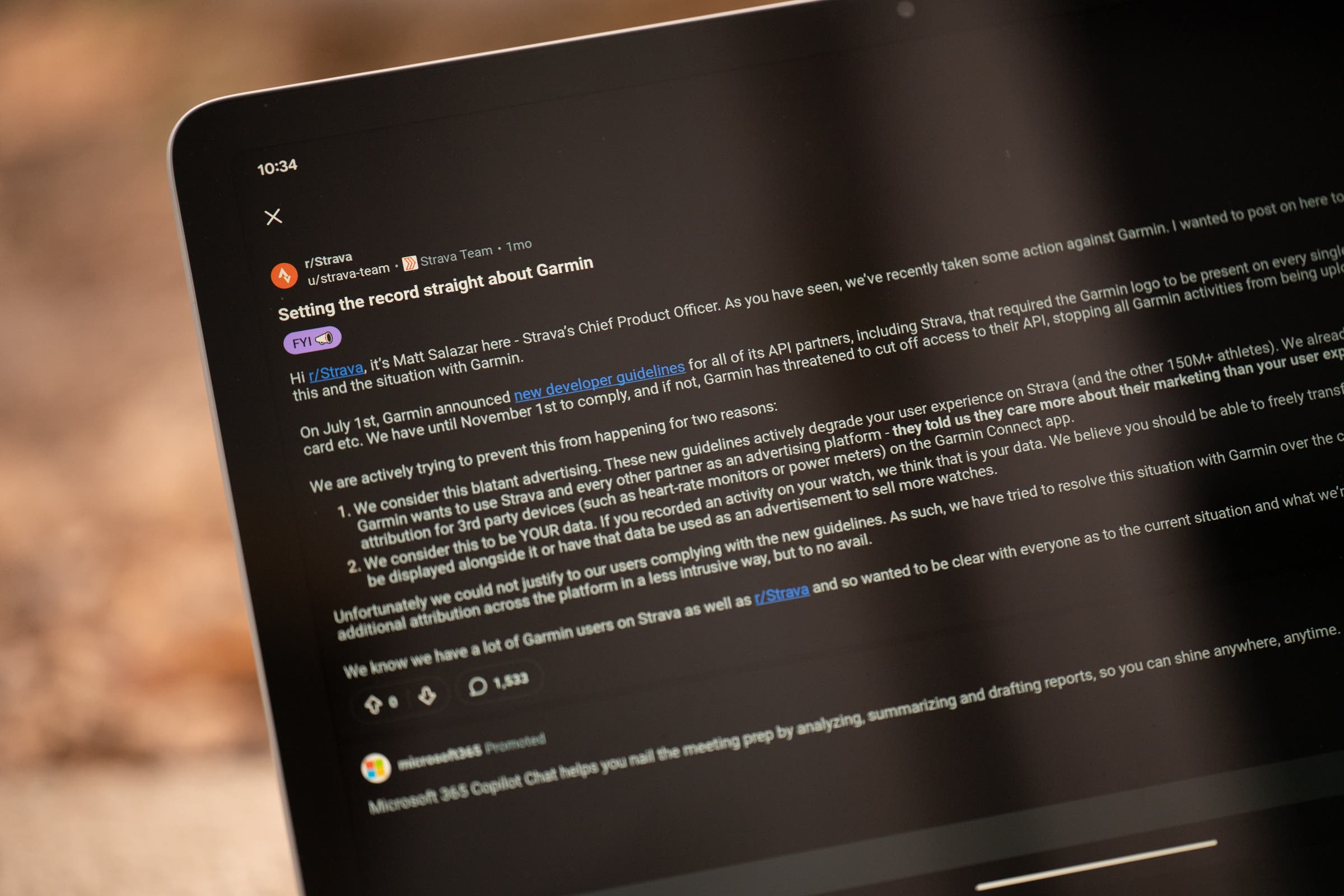

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)What we do have insight into is the Strava response. Strava filed a suit against Garmin in response. It alleged copyright infringement, but it wasn’t really about that as Strava’s chief product officer Matt Salazar explained in a 325-word Reddit post. In that post, Salazar explains that Strava considered the Garmin API change to be “blatant advertising.” He went on to say “We consider this to be YOUR data. If you recorded an activity on your watch, we think that is your data. We believe you should be able to freely transfer or upload that data…”

Now in that post Salazar is talking specifically about the logo requirement but it’s hard not to draw a parallel there. “We believe you should be able to freely transfer or upload that data” unless, I guess, you want to transfer it out of Strava to a third party. Of course Reddit users responded to the post with that exact line of thinking. Again users were not happy and many pledged to drop Strava the moment Garmin uploads encountered an issue. Some even dropped it in response to the suit.

In the end, Strava dropped the suit and implemented the logo requirement a few days ahead of the November 1 deadline. Nothing shifted in the Garmin API requirement.

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)

(Photo Josh Ross/Velo)What does Strava say and what did it gain?

A little over a week ago, I asked Strava a series of questions with the intent of giving the company the option to revisit past decisions with the benefit of hindsight.

What was the strategy being pursued going back to the API change last year?

Is that still the same path Strava is executing or is there a different path at this point?

Is the company surprised at user response or was that expected?

Looking back on it, is there anything Strava might have done differently?

Unfortunately Strava was unable to dedicate time for someone to respond so we are left to guess. We are also left to guess if Strava gained anything — but it seems like the answer is no.

A company that was once well loved garnered a ton of user negativity through a series of choices spread over many years. Strava did become profitable in 2020 after the removal of features, but a global pandemic that gave a huge boost to fitness brands also helped. Since last year, with the move to restrict the API, there’s also been a very real sidelining of Strava for athletes looking for performance gains. Previously you’d connect Strava to a more performance focused software and now that’s not possible. That will lose a segment that is likely a small part of the user base but also a real driver of more casual use.

Strava does continue to have an ace in the hole though. In today’s world Strava is an important player in the social media landscape. It doesn’t matter how upset people are with the business practices, users aren’t leaving in serious numbers. Uploading an activity and getting comments and kudos is a powerful draw. The new core feature of Strava is the social graph, not the features.

At the same, that’s a problem for Strava. There’s no ads because revenue is driven by subscriptions. Except that the core draw of the service is something that doesn’t generate money.

Looking back you can see how Strava won against the competition but has always had the same problem of making money. Over the years the company has protected more and more features with subscriptions and API access. The result is that the core draw has continued to focus more and more into social media and that’s something that doesn’t make money with the current structure.

Now I wonder, will ads come next? And is there a breaking point for users? As the company looks to go public soon, those questions will be more important than ever.

.png)