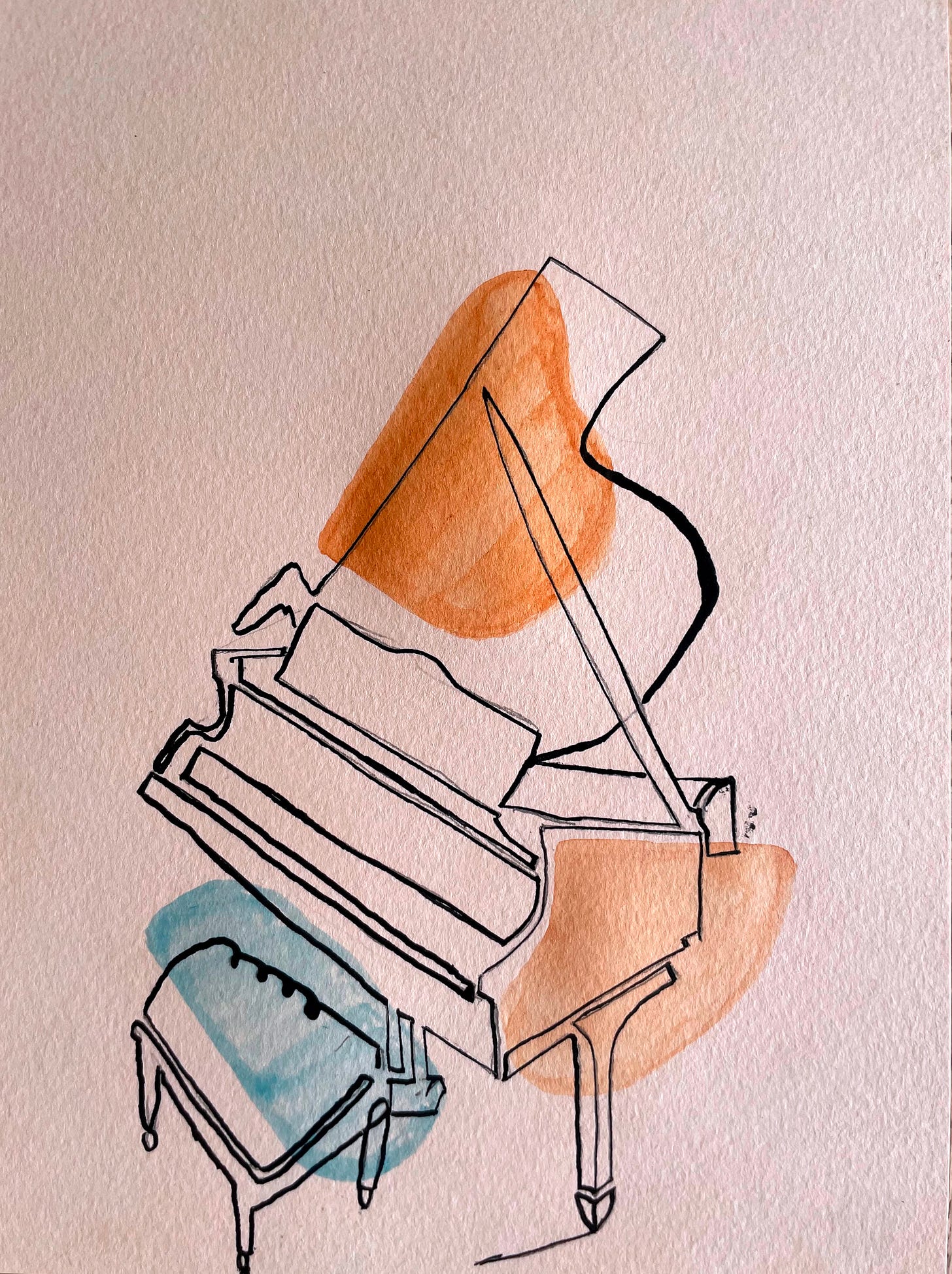

This is going to take 40 minutes to read. Please enjoy this music, specially created for this piece by a wonderful human, Sarthak Dev, a pianist, a writer, and someone who believes Floyd, food, and football can bring world peace. I am only one-third with him on the food, but 100% with him on his music and writing.

The siege of Sarajevo lasted for 1,425 days.

On Ferhadija Street, a part of Sarajevo dating back to the 16th century, the buildings, most of which were constructed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, had a Germanic feel to them. Towards the more Eastern side of the street, there is a more Ottoman feel to it, and the two styles blend in together into the fabric of the city. And yet these were not times when one appreciated the cultural potpourri that was Sarajevo.

Wednesday, 27th May 1992

The siege had just begun, and the city had started experiencing its first food shortages. The bread lines got longer because, just like hope, it was in short supply. People were waiting patiently, getting a taste of the shortages for the years to come. But this Wednesday morning had something different in store.

From the high hills of Sarajevo, the Serbian forces bombed the street, killing 22 civilians and wounding more than 200. The street was strewn with corpses, the injured who lost limbs and many were weeping from shock. Sarajevo TV showed an elderly man, still clutching his bread, leaning helplessly against the wall with blood pouring from his face. A woman sitting in streams of blood reached out feebly for help. In the museum of Genocide and War Crimes in Sarajevo, one can see the installation of ‘A man who waited in line for bread’ - which is a sculpture of a man made entirely out of bread, shrugging his hands, maybe at the state of despair of his country.

Thursday, 28th May 1992

At the site of the blast, Vedran Smailović, the principal cellist of the Sarajevo Opera House, began to play Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor, a piece that had been found in ruined Dresden in World War II. However, the symphony was found incomplete, and Albinoni’s biographer Remo Giazotto then constructed the balance of the complete single-movement work based on this fragmentary theme.

You can listen to it here to feel joy, sorrow, disappointment and hope in just 9 minutes.

Smailović continued to play for twenty-two days, sometimes even as he came under sniper fire. One day each for the 22 people who had been killed in the attack. It was an act of defiance and artistic expression, as if this act was the very embodiment of the words of Pablo Picasso

“What do you think an artist is? An imbecile who only has eyes, if he is a painter, or ears if he is a musician, or a lyre in every chamber of his heart if he is a poet, or even, if he is a boxer, just his muscles? Far from it: at the same time, he is also a political being, constantly aware of the heartbreaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image. How could it be possible to feel no interest in other people, and with a cool indifference to detach yourself from the very life which they bring to you so abundantly? No, painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war.”

I have often thought of this quote by Picasso, in times of strife, personal failures and seemingly insurmountable challenges to the state of my country and culture. But never did I imagine I would be thinking of this when I thought of how art is intersecting with AI.

Why?

Because the advent of AI seems to be an epoch in the Anthropocene. There is little doubt that many aspects of human existence will benefit incredibly from it. In the medical sciences, we are likely to see enhanced drug discovery and development to mainstreaming of personal medicine. Even on the environmental front, AI could detect illegal activities like poaching and predict environmental threats, and it could help us model climate change better.

But AI in art?

This is a personal struggle. I have been sitting with this question for months. As someone who enjoys loves writing this long-form newsletter, I have asked myself - Does AI write better than I? If not already, is it going to happen in the future? What is the point of my writing then, the countless hours I spend researching, thinking, writing and creating original art for this? Are text and image LLMs going to be the way art is going to be created in the future? And I cannot even imagine the questions that professional artists go through, especially when their art could compete with AI-generated art in the marketplace of creativity.

This piece has been a long time in the making, and maybe this entire essay will age poorly. But here I am, because the point of an essay is to explore your thoughts and ideas. So to begin, we turn to an art form, which at the moment, is least likely to be impacted by AI.

Dance.

The woman who broke Kathak

In 1948, a girl, barely 18 years old, living in Bombay, cocooned in the haven of her grandparents’ care, found herself on a flight to London. Till then, she had formally trained and worked in two fields, which did not have a lot in common: agriculture and architecture.

But the reason she was on a flight to London had nothing to do with either.

It had everything to do with dance, and unknown to everyone, most of all the girl herself, it was her professional foray into an ancient dance form that launched a trailblazing career. The seeds were sown, and there began the journey of a formidable artist who, over 67 years, broke Kathak, time and again.

Kathak is a North Indian classical dance form that dates back to Vedic times, roughly between 1500 BCE to 500 BCE, and is firmly rooted in the tradition of mythology. The first Kathak dancers, or Kathakars as they were called, were essentially travelling bards; they visited the temples and towns across the Gangetic Plains (Fertile flatlands in northern India, through which the holy river Ganga flows). They spread mythological stories of Krishna (a Hindu god) and his world through words, dance, music and mime. While temple priests regarded these bards as useful vehicles to spread Hindu lore to the masses, royal families employed Kathakars as entertainers.

As an oral tradition, early Kathak was handed down from generation to generation via the spoken word, and each new generation of Kathakars added its interpretations to the profession. Over centuries, the dance form kept adapting, but the largest transition happened in the 16th and 17th centuries with the arrival of the Mughals (a dynasty with its roots in Central Asia). Kathak was integrated into their courts, and its technical vocabulary expanded, influenced by the influence of Persian performers, gharanedar (hereditary dance teachers) and tawaifs (courtesans). Later, during the British colonial period, all Indian classical dance forms experienced a severe decline because the artistry, context and technique of Indian Classical art forms were outside the bounds of the British understanding of art. Kathak had to additionally face the ignominy of not even being seen as an art form, and came to be heavily associated with tawaifs (who made significant contributions, but were not the only practitioners) and prostitution (difficult to say how much of it is true).

It was only in the early half of the 20th century, in tandem with the freedom movements and calls for self-governance, that these forms were rejuvenated.

But it came with a problem.

As India gained independence in 1947, the government harnessed dance to help shape national identity. Classical dances became cultural markers, ways to depict true ‘Indianness’.

Whenever we associate an art form with national identity and pride, there emerges an entire ecosystem of actors who want to ‘preserve’ the purity of the form: Critics, gatekeepers and the worst of them all: The artists themselves.

It’s in this milieu that the young girl, who went by the name of Kumudini Lakhia (born Kumudini Jaykar), started training in Kathak. For those unfamiliar with how training works in Indian classical dance (and music), here is a quick primer:

The Guru Shishya Parampara is a traditional system of learning and knowledge transmission, where a Guru (teacher) imparts knowledge and skills to a Shishya (student) through a personal, dedicated mentorship. This method is not just about learning steps but about understanding the art's spirit and soul, ensuring the essence of the art form is passed down through generations. Information, including techniques and insights, is often passed down orally, allowing for the unique style and nuances of the Guru to be imprinted on the Shishya.

As Kumudini progressed through her training, she was mentored by multiple teachers of repute. Some of these teachers were fierce taskmasters: Shambu Maharaj was one such guru, who only came into the room to teach if he saw a ring of sweat around the dancers’ bodies from practising their footwork. But she also worked and learnt from those who had presented Kathak at the international stage, like Ram Gopal. The flight to London was for her to participate in an ensemble cast of Indian dancers. While the show was unimaginatively called ‘Dances of India’, the treatment was anything but. For the time, it was the most comprehensive and sensitively presented show of Indian dance in Europe - conceived and performed entirely by Indian dancers without reference to western choreography.

The performance was received with enthusiasm, with one of the reviews in the Daily Telegraph saying

The quality of the performance is unmistakable. Exquisite colour, miraculous grace of posture and movement and the fascination of sheer virtuosity make a strong appeal even to the most ignorant western spectator.

Over the years, as the show moved around, it continued to gain popularity. In Sweden, in particular, the sold-out audiences were so enthralled that the troupe was requested to return at the end of its tour to perform again. In London, the city was covered with posters depicting a large picture of Kumudini (amongst others) in dance poses.

And yet Kumudini, still a young woman deepening her understanding of Kathak and the world, saw that this interest was primarily motivated by an exotic allure rather than dance form as art.

But the western reception to Indian dance was the least of her problems. She had a bigger problem to deal with back in India, specifically in Delhi (a city she now lived in) - the cultural and political centre of Kathak.

Political centre of Kathak?

The ecosystem of ‘preservers’ of Kathak was strictly against any experimentation with form. Two aspects were considered cardinal

Kathak is fundamentally a solo performance, which places great emphasis on technique as pure virtuosity and entertainment, and is a reflection of the traditions of the guru you learn from.

The themes must come from mythology, and primarily narrate the stories that have been narrated for centuries.

Kumudini was not militantly against the traditions of Kathak. In a 2002 interview, she stated, “As inheritors of the art, it was our responsibility to acknowledge its greatness and not violate its spirit, dilute or trivialise it.”

But for all her respect for the tradition, Kumudini was also at odds with such ideas.

She did not wish to define Kathak through the rhetoric of ancient purity and religious connection to gain approval as an artist. It was not her job, she thought, to defend the moral parameters of Kathak. She refused to entertain the idea that female dancers could only gain validation by disguising themselves as cultural relics, wrapped in the chaste image of India’s ancient past.

“I can’t be holding up flags for anybody”, she said firmly, “I need both hands free to dance”

As a matter of personal circumstance, she relocated from Delhi to Ahmedabad, a city in the western part of India, with little to no Kathak tradition or schools to speak of.

For all practical purposes, she was confined to the margins of Kathak.

And from these margins, quietly at first, and not so quietly later, one student and performance at a time, working out of the office of her husband, which doubled up as her studio in the evenings, Kumudini broke Kathak.

She had borrowed from the words of one of her teachers, Ram Gopal, with whom she had done her London tour

“You’ve perfected the technique, now throw it overboard and dance”

And oh boy, did she dance!

Kathak is one of the most fluid of Indian classical dances with regard to structure. Its fragmented nature and open-ended format allow for much variation and improvisation, and this is one of its strengths and attractions as a classical form.

For Kumudini, Kathak was not about strict adherence or complete disregard for tradition. Training requires an appreciation of Kathak beyond performance and product. Kumudini’s passion was for movement, pure and simple.

In the margins in Ahmedabad, Kumudini broke the first cardinal rule: She moved away from solo performances to group performances and choreography. In 1973, at the Navnrityotsava Festival (open to all classical dancers), saw the debut of one of her group choreography pieces, Dhabkar.

But even before she could get started, there was a spanner in the works. The tabla (a pair of hand drums central to Kathak) player suddenly disappeared on the day of the show, and she had to scramble last minute to find a replacement. She sat with the replacement during the performance, reminding him of how many avartans (time-cycles) to wait, helping him with compositions, and making sure he maintained his tempo, all the while quietly cursing the missing tabla player.

When the piece ended, Kumudini was stunned. The audience clapped instantly. “We could not believe it was such a success”, she said “I remember we couldn’t sleep at night, so we stayed up and talked about the show. We knew that very day that we had done something different.”

But Dabhkar also presented the Delhi circuit of Kathak with firsts, from costumes to dance formations. The critics lashed out at her, questioning the continuity of tradition. In Kumudini’s words

“The white costumes they called a funeral procession, the lack of dupattas they called shameful, and the splitting up of the movements they thought of as sacrilege. No one had heard of choreography at that time. They did not know what I was doing, I did not know what I was doing. They thought I was a passing phase in Kathak”

By then, she had established her school called Kadamb. She teamed up with Atul Desai, an unlikely musician, who could compose music specifically for Kathak. A trained vocalist and an experimental man himself, he then brought another dimension to Kathak, which is unimaginable.

Take your wildest guess.

Atul introduced Electronic Music.

A far cry from the traditional string and drum instruments of Indian classical music.

And then Kumudini broke the ultimate rule. She moved away from mythological themes and brought the personal into dance. In 1981, in a matter of just three months, she composed a piece, Atah Kim, meaning ‘What next?’ or ‘Where do we go from here?’.

The theme grew out of a sense of uncertainty, an emotion that Kumudini struggled with since childhood - The early loss of her mother, her discomfort with the classical form of Kathak and being at odds with the Delhi circuit and where she fit into it, the uncertainty of building a new Kathak from the margins. The piece is only 25 minutes, and it does not have a single narrative thread. All there is, is a tension, unresolved and ever present.

As someone who writes, podcasts, sketches and watercolours, I find myself in my moment of Atah Kim. The age of AI is my moment of uncertainty as an artist - What is the meaning of my art in the age of AI, when probabilistic reproduction of text and images could probably (certainly?) surpass my creations? How far away are we from a point where human and AI art are indistinguishable? Are we already there, and am I the sucker on the poker table?

Even if there comes a point when AI starts making art comparable to a human, it would fundamentally fail at two things, and I return to Atul Desai, Kumudini’s musical partner in crime. He says

Tradition and innovation are cyclical and feed off one another. When art is saturated with innovation, it will naturally return to tradition, which is like an axis. It does not rotate much but innovation revolves around it

Art needs its margins to innovate. The margin exists because the mainstream does not acknowledge it. The margin first festers and seethes with rage, then quietly accepts its current state, and starts building a body of work that becomes so formidable that it pushes the mainstream, and the mainstream cannot afford to ignore it any longer.

Just like Kumudini, confined to the margins, had her work criticised as sacrilege. Her Kathak emerged from a trial by fire, fueled by the disdain of an unrelenting mainstream. Today, her work is considered a classic and continues to inspire novel approaches to Kathak. Atah Kim, in amalgamated forms, continues to be performed, even after 40 years, when she conceptualised it in the margins.

In April 2025, we unfortunately lost Kumudini at the age of 95. But if I were to capture her legacy, I would go back to her own words

“What did I do to Kathak? I gave it an acid bath.”

The one thing that AI art cannot do is incorporate the margins. Why?

For that, let’s understand how Large Language Models (LLMs) and Image Models, more popularly known as Generative AI tools, the output of whom we use to generate AI art.

Understanding why AI produces the writing it does

All LLMs use existing writing on the internet as a base for their writing. This existing writing is known as Corpus and determines the words that the LLM knows and understands.

So if I define a new word, as nonsensical as ps12tywe, the LLM does not know it because it’s not in the corpus (and will not be since I don’t allow Substack to give access to LLMs to train on my writing).

At the heart of it, LLMs are a prediction machine. Its job is to predict the next word - So if you write “The quick brown fox”, it will most likely complete the sentence as “jumps over the lazy dog”

Why?

Because this is a popular sentence and would have occurred in the corpus numerous times. What the LLM does is that it stores the probability of which word would come next, given preceding words.

So, what happens when we ask ChatGPT or Perplexity a question, or give it a prompt?

It makes a series of predictions of text, which we see as an output. Under the hood, it’s all mathematics. Probabilities are getting used, and that brings us to an important aspect of how the final set of words is decided.

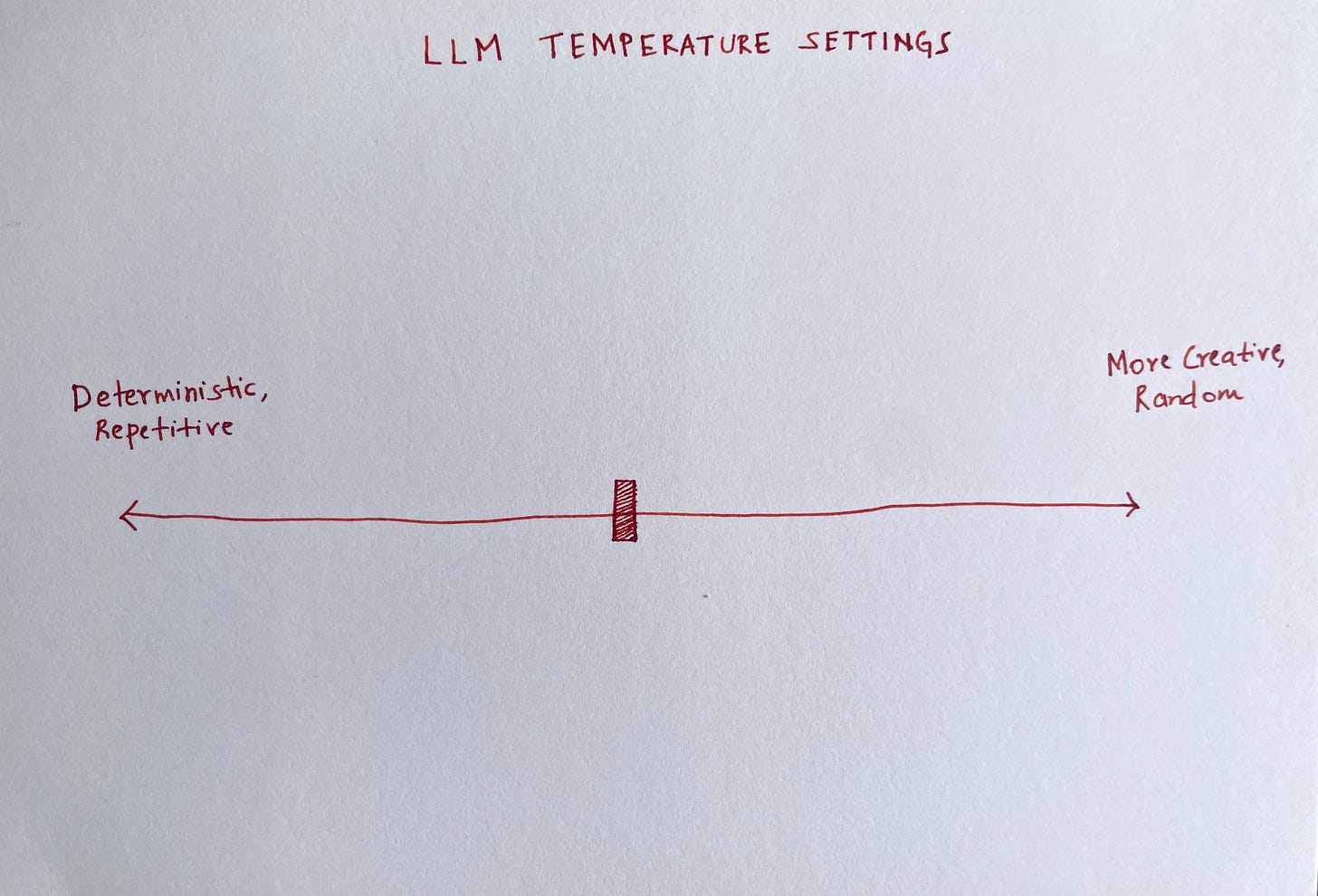

Temperature.

Temperature controls how random the output of an LLM is. If the randomness is too low, then the text is too boring, clunky, and bland (deterministic), and if it is too high, it is all over the place and makes no sense at all (random).

To find the right balance of predictions, the LLMs then go through the corpus multiple times. The first time the LLM encounters the corpus, all the predictions stored are random, so the output is equally random.

Each time the LLM goes through the data (epoch), it compares the prediction with the original data.

Then, it notes the difference between the original data and the prediction. The difference is called Loss. By its name, one may feel that the original data and the prediction should be the same, and the loss must be zero.

But if you reduce the loss too much (and there are limits to how much it can be reduced), there will be very little novelty left in it, and the prediction will be boring.

So LLMs arrive at some middle ground of temperature, where the novelty and boringness are balanced.

This is a significant reason why the early iterations of a question / prompt with an LLM have this middle of the ground, neutral, no point view kind of output, which while technically correct, will do nothing for the reader.

And this is one reason why AI art, in its initial iterations, is so underwhelming, and has the name - AI slop

AI slop exists for two reasons

One, the LLM, in its attempt to find the balance between novelty and boringness, produces middling outputs with no point of view.

Two, many people, owing to early exposure to LLMs and not realising the value of iterations, put out stuff which is pretty much the first few iterations. They take minimal effort to make it personal or meaningful.

This is one reason why AI art has trouble incorporating the margins. While the margin may exist in the corpus in some form, the probability of it showing up in an output is so low that only after countless iterations it will only possibly show up in an output. The margins are one extreme of the temperature scale, on the side of novelty

Anu Atluru has beautifully termed it as the Unmodelable Edge.

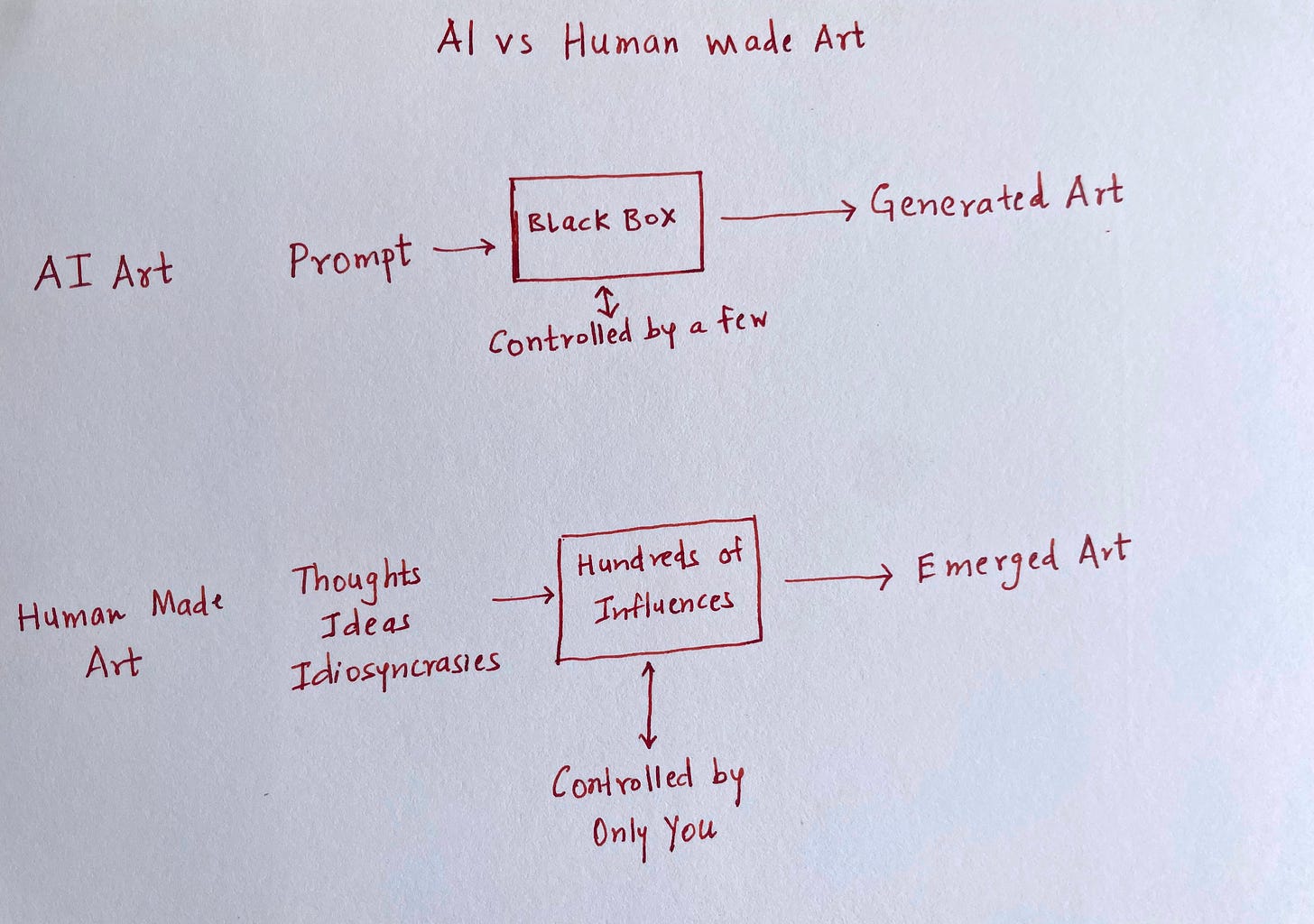

But there is another reason, which is at the heart of the structure of LLMs, that makes me believe that AI art will never be as good or meaningful as human-made art.

And for that, we will understand two kinds of memory.

The nature of our memories

Human beings have two distinct types of long-term memory - they differ in the kind of information they store and how that information is experienced and used.

Semantic memory stores general world knowledge, facts, concepts, and meanings that are not tied to personal experience. Think mindblowing facts such as whales are older than trees, and butterflies drink tears of turtles to add salt to their diet.

Episodic memory stores personal experiences and specific events that happened at particular times and places, along with contextual details like emotions. Episodic memory is flexible, as it is not about regularities, but about peculiarities. Unlike facts, peculiarities cannot be mass-produced; they are intensely personal. Your first kiss, the birth of your child and the death of a loved one are all episodic memories.

LLMs don’t have episodic memories because they have no lived experience. They feel nothing because they have no experience of anything. They lack context, and without context, there is no meaning.

And it is for this reason, for e.g. AI cannot write about grief, because the experience is so visceral and personal, that even if trained on the expressions of grief in its corpus, it cannot write about it in a way that would feel human.

Without feeling the uncertainties which Kumudini felt - of her grief, her loss and her insecurities, no AI could create Atah Kim, even in a form which is not dance. Where is the internal fermentation and churn? Where is the stumbling self confidence and crippling self doubt?

Or even consider something far more mundane, this piece itself. Would AI consider using the element of dance in this piece? I was fortunate to have access to the kindness, expertise and wisdom of Eshna Benegal, who has trained for 17 years in both Kathak and Odissi (another Indian classical dance form). We could sit down and have a conversation about the fundamentals and nuances of dance, dive into her episodic memories, and distil the meaning and the place dance holds in her heart. The story of Kumudini Lakhia would not have made it here had it not been for her. I was fortunate to have access to Sarthak Dev, to whom I reached out on a lark, and he was so kind to compose the piece you may be listening to as you read this. He read early drafts of this essay, gave me tunes to get a vibe of the music he was thinking of, and asked me about instrument preferences and choices. We could discuss these in the context of the essay (Should we use the synthesiser sound or not?), and out came this beautiful piece of music, from a man who can somehow make music and sports writing belong to the same universe.

I could share my Atah Kim with Eshna and Sarthak, and they responded as artists, not pattern prediction machines. Could AI have done that for me?

But even if AI can model episodic memories, there is yet another reason why it will never be as good.

And to understand that, we shall rely on my favourite subject, Mathematics, and of course, the power that runs the universe - Cats.

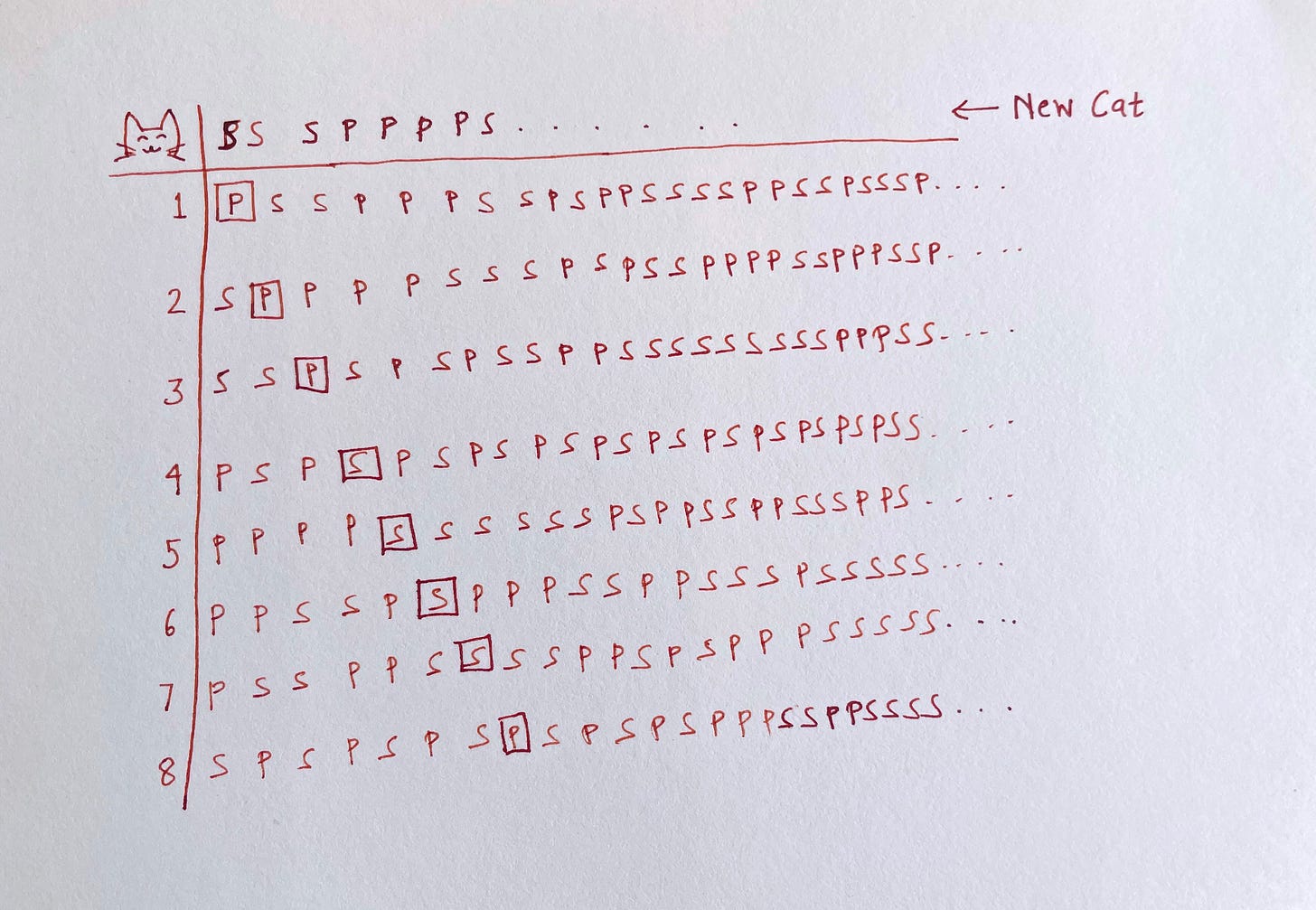

The paradox of infinite cats in boxes

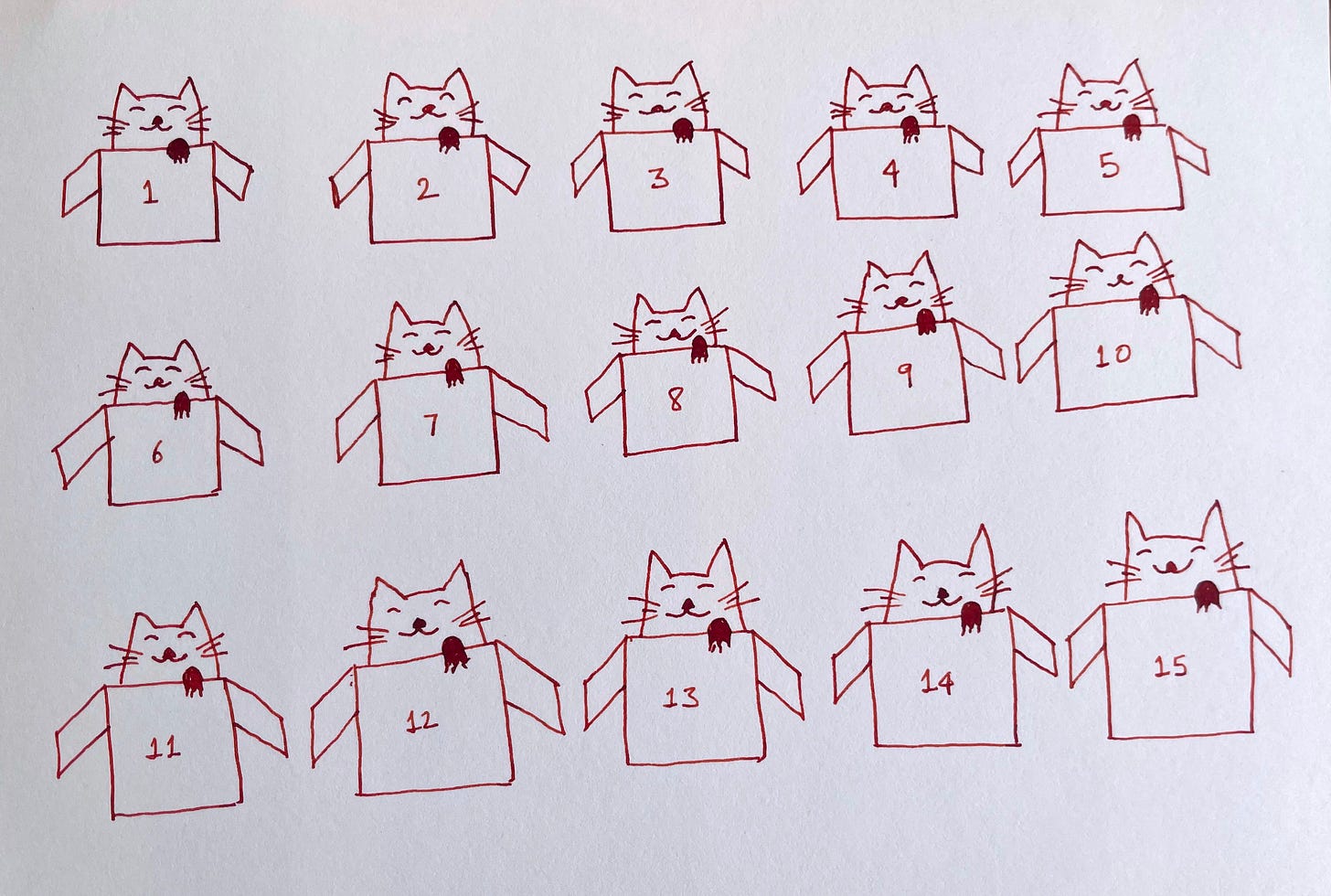

Imagine a planet where only cats exist. They don’t live in homes or sleep on fancy beds. They live in delivery boxes, so this planet only has delivery boxes.

Now, imagine that this planet has infinite cats. Each cat has been given one box, and since there are also infinite boxes, no cat is without a box of its own.

We number these boxes starting from 1, 2, 3 … up to infinity.

Now, thanks to interplanetary travel, a new cat arrives on this planet. The Big Cat of this planet is a nice and welcoming chap, and says, of course, we have room a box for you. He knows that all the infinite boxes have one cat each, so technically, there is no extra box.

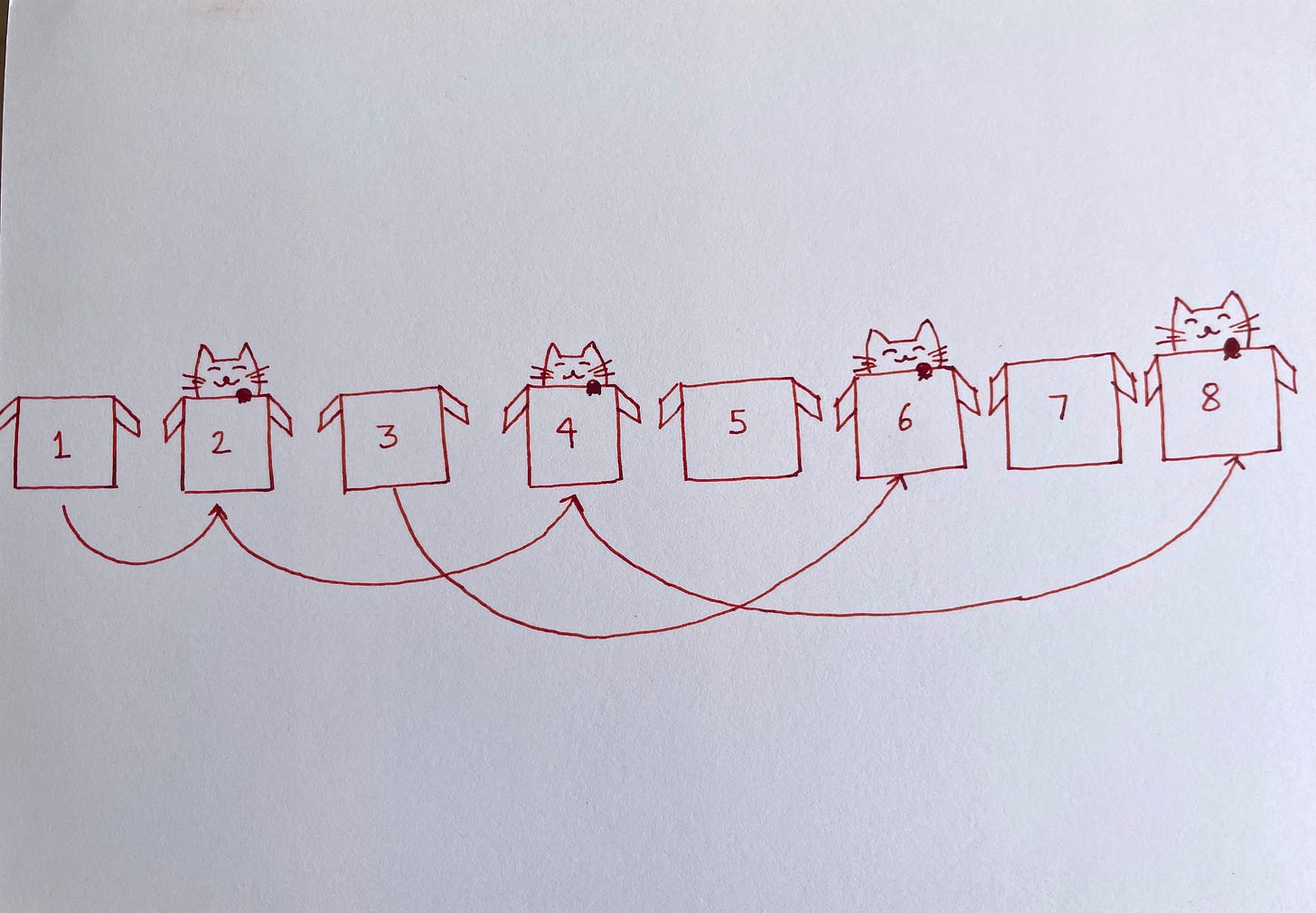

But he simply asks all the cats to shift to the next box. The cat from box 1 shifts to box 2, the one from box 2 shifts to box 3 and so on …

And the visitor cat is accommodated in box 1.

News of this welcoming planet spreads through the felinesphere, and a new batch of 100 cats arrives. The Big Cat is thrilled and asks all the cats to shift by 100 boxes. The cat from box 1 shifts to box 101, the one from box 2 shifts to box 102 and so on …

And the new bunch of cats are also accommodated. Good on you, Big Cat!

The felinesphere can scarcely believe the generosity of this planet, and now suddenly, there is an infinite set of new cats arriving. Big Cat is nonplussed and asks all the cats to shift to the box number, which is twice their current number.

The cat from box 1 shifts to box 2, the one from box 2 shifts to box 4 and so on …

Now all odd-numbered boxes are free - There is no cat in box 1, 3, 5, 7, etc,. and since there are infinite odd numbers, this new set of infinite cats also has a box each to themselves.

Big Cat becomes a celebrity. Crowds offer catnip at his feet, his sleep time is zealously protected, and there is always food by his side.

By now, the news has spread to other galaxies, and a new set of infinite cats arrives. They are peculiar in one way - All of them have unique names, each made up of a combination of only 2 letters - p and s. Some of these names include

pspspspsps, ssssppsspspsps, pppspssspss etc.

These cats now request Big Cat to accommodate them.

Big Cat says NO. I have no more space on my planet. I am out of boxes.

And all intergalactic hell breaks loose.

But but .. you have infinite boxes, how can you ever be out of boxes? Big Cat also secretly had an MBA from Purrvard Business School, so he pulls out a spreadsheet. He goes on to show how he would start accommodating people

He says

If I were to pick the first letter of Cat 1’s name, the second letter of Cat 2’s name, the third letter of Cat 3’s name and then change every p to s, and every s to p, I would find a new cat name from your set of infinite cats. I can do this an infinite number of times, and I will keep finding a new cat.

Why? Because the name of each cat would differ from the name of any other cat by at least one p or s, the one that we borrow and change.

But I will never have enough boxes for them.

The new set of infinite cats understand, thank the Big Cat for its honesty, and head back home.

Did it make sense?

In the first scenario, where there are infinite cats, each having a unique number, there are infinite boxes, and that is an example of Countable Infinity.

In the second scenario, when each cat has a name with a combination of p and s, there are way more cats than the boxes, and they can never be counted, and that is an example of Uncountable Infinity.

So we have countably infinite boxes, but uncountably infinite cats.

Did it make sense now?

Well, if it did not, you are in elite company. When this was first proposed in 1874, it unleashed absolute mayhem in the world of mathematics. Or, if I may say, put the cat out amongst the pigeons mathematicians.

How can something that continues forever be bigger than something that continues forever?

And of course, Cantor and the mathematical community were not talking about cats in boxes, but they were referring to

Natural numbers (1,2,3,4 …) which are countably infinite, and

Real numbers (0.1, 1/2, -5, etc.), i.e. positive and negative integers, fractions, and irrational numbers, which are uncountably infinite.

He had proved that, despite both being infinite, the set of real numbers is larger than the set of natural numbers.

Cantor’s work was labelled ‘a horror’, ‘a grave disease’. One of the most well-known mathematicians in history, Carl Friedrich Gauss's said: "Infinity is nothing more than a figure of speech which helps us talk about limits. The notion of a completed infinity doesn't belong in mathematics.”

Cantor’s teacher and mentor, Kronecker, was his fiercest critic, publicly denouncing him with harsh epithets such as "scientific charlatan," "renegade," and "corrupter of youth." He went on to consistently deny him teaching positions at the University of Berlin, which was Cantor’s preferred place to work. Kronecker's distrust was deep, going as far as delaying the publication of his 1874 paper that first proposed the idea. In 1885, as Cantor continued to work on what is now formally called ‘Set Theory’, the mathematician Mittag-Leffler persuaded Cantor to withdraw a paper from publication because it was considered "about one hundred years too soon,". Even amongst those who were sympathetic to his work, there was a distinct lack of appreciation and support.

Cantor also drew flak from philosophers and theologians because the idea of infinity mattered to them, too. Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian philosopher, later criticised Cantor’s advanced work as "utter nonsense" and "laughable.". Spinoza, a Portuguese-Dutch philosopher, defended the idea of one "absolutely infinite" substance (God or nature) and resisted the idea that infinite numbers could be meaningfully divided or completed. Theologians objected to Cantor’s theory because it seemed to challenge the uniqueness of God’s absolute infinity. They feared that admitting actual infinities outside of God’s nature compromised theological doctrines..

Because it went against the idea of infinity, which everyone understood intuitively (and is pretty much the idea that we all have).

All this backlash broke Cantor. Starting in 1884, he had recurring bouts of depression. He was hospitalised multiple times and spent much of his later life struggling with mental illness, which has been partly attributed to the hostile environment created by his opponents.

And yet, there were a few who saw through the genius of Cantor. Foremost amongst them was David Hilbert, who famously defended Cantor’s work, declaring, "No one shall expel us from the paradise that Cantor has created."

The Paradise: Starting with the idea of unequal infinities, going right up to Set Theory.

Over time, historians and mathematicians recognised Cantor’s pioneering role in creating a rigorous theory of infinite sets and different infinities, marking him as a foundational figure in modern mathematics.

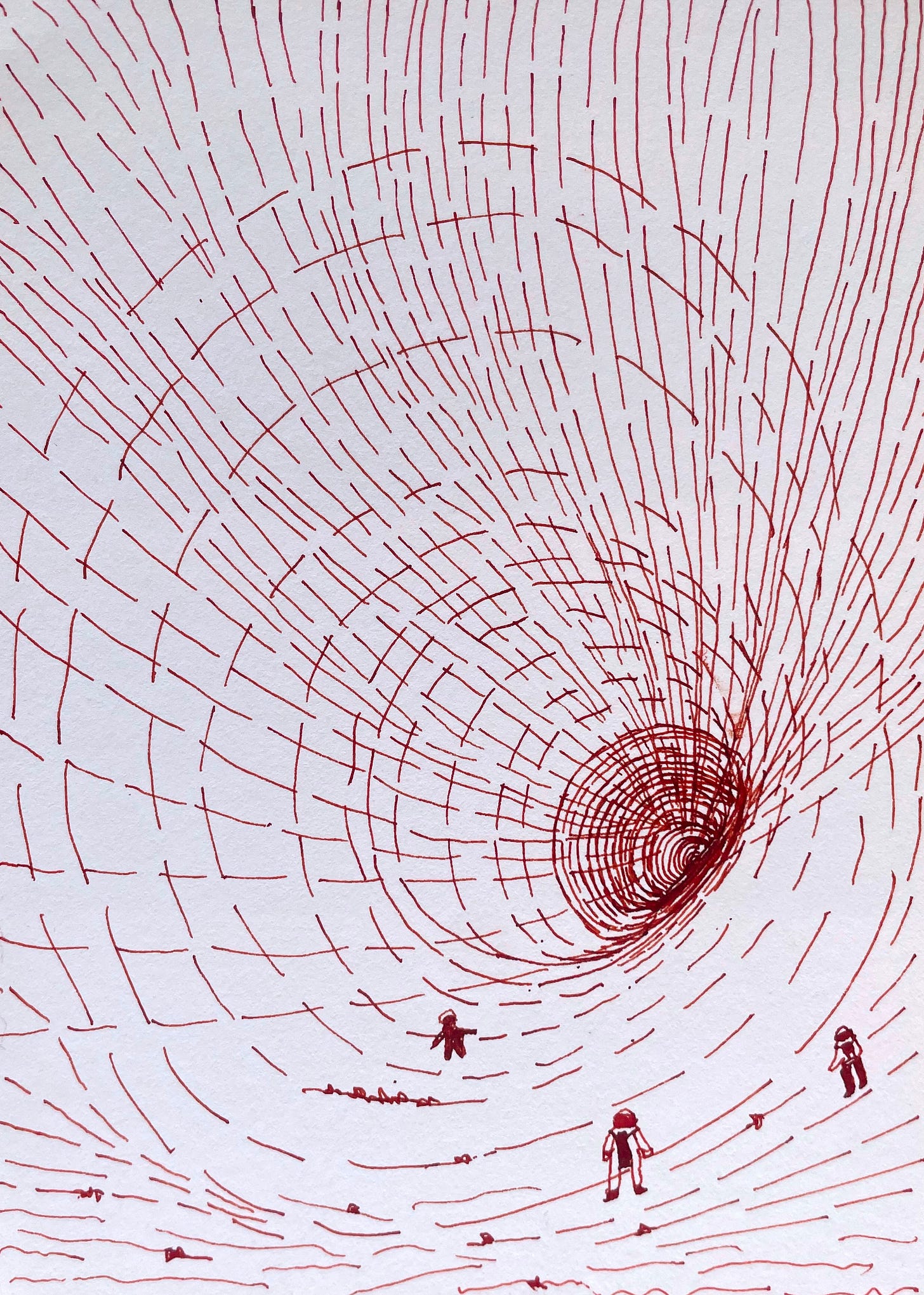

The idea of countable and uncountable infinities is how we can crudely conceptualise how AI and humans absorb, think and create art.

If LLMs are trained on trillions upon trillions of data points, one could still consider it as a countable infinity, whereas the human mind, with its breadth of experiences, thoughts, actions and access to other humans, would have data points which one could count as uncountable infinities.

And one could argue that LLMs would ingest more and more data as we go along, and there would come a point where their ability to do art would far surpass a human being. And isn’t all we write and create, an amalgamation of our thoughts and ideas, already encoded into our work, and by accessing that, LLMs have access to our inner selves?

There is one problem with the argument. It assumes that humans can express in language (verbal and visual) the entirety of their thoughts.

Neuroscience says otherwise.

The pianist who could not read notes

A letter landed on Dr. Oliver Sacks's desk in January 1999. Oliver was a great neurologist, historian, and poet of science. In his obituary in The New York Times, he was described as "a man of contradictions: candid and guarded, gregarious and solitary, clinical and compassionate, scientific and poetic." Receiving such a letter was not uncommon for him since he accepted a very limited number of private patients, despite being in great demand for such consultations. He usually wrote back to these patients, but there was something different about this letter, and he had to pick up the phone.

Dear Dr Sacks

My (very unusual) problem, in one sentence, and in non-medical terms, is: I can’t read, I can’t read music, or anything else. In the ophthalmologist’s office, I can read the individual letters on the eye chart down to the last line. But I cannot read words, and music gives me the same problem. I have struggled with this for years, have been to the best doctors, and no one has been able to help. I would be ever so happy and grateful if you could find the time to see me.

Sincerely yours

Lilian Kallir

The problem was rather acute for Lilian, for she was no hobbyist musician. She had given her first public concert at the age of four, and Gary Graffman, the celebrated pianist, called her “one of the most naturally musical people I’ve ever known”. She was only 16 when she won the National Music League Award and the American Artists Award of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, but a year older when she made her début with the New York Philharmonic, and 18 when she gave her début recital in New York Town Hall. Her central repertoire - Mozart, Schubert, Brahms - just flowed out of her. For the conductor Jonathan Sternberg, "Her playing displayed an interpretative approach that manifested a penetrating musical maturity and judgement, flowered by many moments of poetry.”

And now she could not read sheet music.

She wrote to Oliver when she was 67, but only when he met with her at his clinic did she reveal something else.

She has been living with this condition for almost 20 years.

Her first recollection of something being off came during a concert in 1991. She was performing Mozart piano concertos, and there was a last-minute change in the program, from the Nineteenth Piano Concerto to the Twenty-First. But when she flipped open the score of the Twenty-First, she found it, to her bewilderment, completely unintelligible. Although she saw the staves, the lines, the individual notes sharp and clear, none of it seemed to hang together, to make sense.

Nonetheless, she went on to perform the concerto flawlessly from memory.

Over the next few months, the problem reoccurred and worsened. She continued to teach, to record and give concerts around the world, she depended increasingly on her musical memory and her extensive repertoire, since it was now impossible for her to learn new music by sight.

By 1994, three years post the first incident, she had trouble reading words. Her ability to write remained largely unaffected, and she continued to maintain a large correspondence with former students and colleagues scattered throughout the world, though she depended increasingly on her husband to read the letters she received, and even to re-read her own.

Lilian was the first person Oliver had encountered whose alexia (inability to recognise or read written words or letters) manifested first with musical notation, a musical alexia.

By 1995, she had trouble seeing things on her right side and had to give up driving. She also developed poor facial recognition. Her speech comprehension, repetition and verbal fluency, though, remained unaffected.

She was eventually diagnosed with Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA), a degenerative brain disease. Her visual difficulties kept increasing - She could no longer navigate things around her own house, had trouble seeing objects right in front of her and had to use spices from the spice rack not by reading their names, but by smelling them.

By then, Oliver had started doing house visits for Lilian or had invited her to his own house. In one of her visits, she started playing a piece she identified as a Haydn quartet that she had heard on the radio. She had arranged it for the piano and had done so entirely in her head, overnight. Before her alexia, she arranged pieces using manuscript paper and the original score, but now she could do it wholly by ear. She felt that her musical memory, her musical imagery, had become stronger, more tenacious, but also more flexible.

It was in her art, her music, that Lilian not only coped with the disease but transcended it. The art of playing the piano demands and provides a sort of superintegration, a total integration of sense and muscle, of body and mind, of memory and fantasy, of intellect and emotion, of one’s whole self, of being alive.

Her piano playing gave her the joy she could still get and give, whatever other problems were now closing in on her.

The muscle memory of an artist, be it a pianist like Lilian, or a sketch artist who makes pen strokes, or a Kathak dancer whose Tatkar (footwork) is unique to them, cannot be expressed in words. As we saw with Lilian, despite so much loss of her ability to read and visually identify faces and objects, her capacity as an artist remained undiminished, as her mind and body adapted.

This language of art, encoded in our hands, feet, ears, eyes and breath, is simply impossible to put into words, a resource an LLM can never access.

If LLMs are a map of the known human knowledge based on the internet, we must remember that the map is not the territory.

And beyond that, AI will not make art that surpasses human-made art for one important reason.

Intentionality.

The intentionality of human art

Ustad Zakir Hussain, widely regarded as the greatest tabla player of his generation and one of its finest percussionists, was once asked a question. His music is known to have transcended genres, and he brought Indian classical music to a global audience and won four Grammy Awards.

The question was

“Aap din main kitne ghante riyaaz karte hain?”(How many hours in a day do you practise)

And he replied

“Kabhi kabhi ruk jaate hain” (Sometimes I stop)

What?

What Ustadji is saying is that even when he is not physically playing the tabla, in his head, he is still playing. If you are a musician, you know this feeling - The compositions floating around in your head. If you are a writer, you know this feeling - The stories, lines and plots living in your head, rent-free. If you are a painter, you know this feeling - The specific shade of lemon yellow you want to try out.

Is this intentional?

I would say yes, because it underscores an important distinction.

The distinction between performance (being performative) and practice

One of the arguments that is thrown in by proponents of AI art is that it has democratized art.

But who has stopped these proponents from picking up a pen and paper to sketch? Who has stopped them from singing badly? Who has stopped them from picking up the brush and watercolour, and making an absolute mess on paper? Didn't all of us do this as kids? Did we ever need AI to do that?

AI has not democratized art. The proponents of AI art are unwilling to suffer the ugliness of practice, the disappointment of being an amateur.

Why?

Because they look at art as just another task. It is performative. Like crunching numbers. If your idea of art is largely prompt-driven, then you have a fundamental disconnect with art.

Art was never about speed and scale; it was about intentionally creating meaning for the self and those who engage with it.

AI art shows a fundamental lack of agency, a lack of intentionality. One may argue that the act of prompting a machine and going through multiple iterations is art. And yes, there is a certain truth to that. AI can be a companion, a sparring partner, someone to bounce ideas with. It can be really useful for people with certain difficulties, it can be helpful for people with neurodivergence to organise their thoughts. But beyond that, those whose idea of art is heavily (if not entirely) reliant on AI

I want to ask

Do they take pride in their art? Do they authoritatively say, “I made this”? Do they have an afterglow as an artist? Do they revel in what they’ve created? Do they need time to rest and recover, or could they have possibly given it their all? Have they ever collapsed, physically or mentally, with exhaustion, with not an ounce of energy left in them, and yet find themselves filled with the unspeakable joy and satisfaction of creation?

Generative AI art is in the service of slop

Your art is in the service of yourself.

The philosophy of AI art is that of an imitator, not of a creator. It is in devotion to the idea of art needing to be efficient. It is about the illusion of mastery, without the devotion to practice.

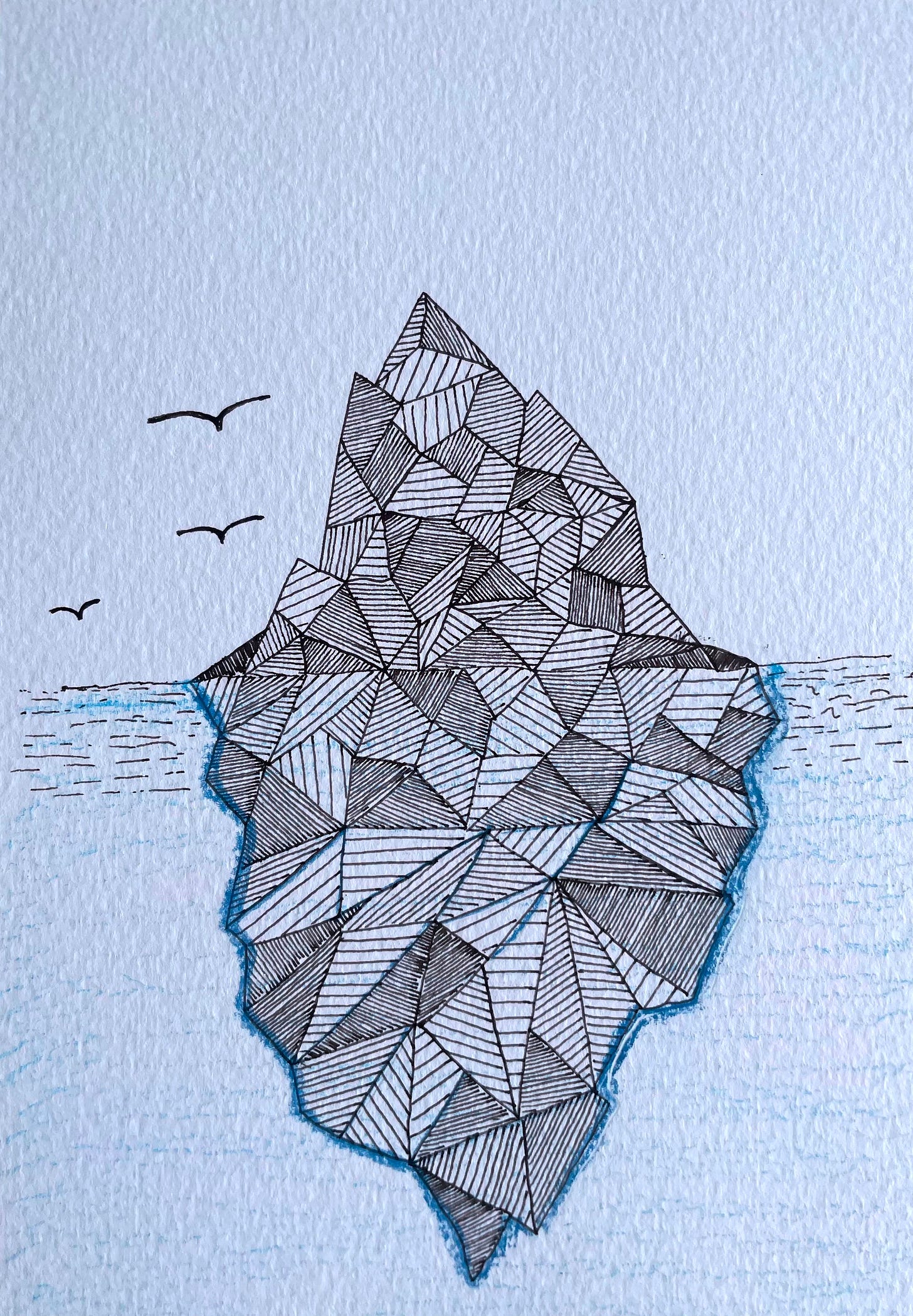

AI art is the reverse iceberg; there is little to no practice, only performance. Human-made art reflects the actual iceberg, so much practice, and the world sees a small part of it.

And why does practice matter? Because practice is learning, about the art, the craft and about oneself. Practice is about building the muscle memory that would sustain and grow you or even survive as an artist, as was the case with the pianist Lilian Kalir. Going through the ugly stages is important because that is an act of becoming, of deepening your relationship with your art and with yourself.

If you think I am being all sentimental about it, look around you (and yes, I recognise that this is anecdotal)

The biggest use of AI art on Substack is writers using it to generate an image for a piece they are writing. Most are happy with anything that looks just about ok and supports the piece. Would the piece hold up without the art? It most likely will, because that image is an afterthought, a performative idea.

In contrast, look at any artist. If you know of anyone who sketches / paints, even those who put their stuff on social media (the epitome of being performative) and those who make a living from their art, only a very small proportion of their art makes it on social media. So much of it resides in their sketchbooks, most likely being seen only by them.

So if AI does not have episodic memories, is built on countably infinite data, cannot create art at the margins and has no intentionality, why are we so worried?

And how should one be an artist in the age of AI?

The worst time to be an artist is the best time to be an artist

Photography did not kill painting, recorded music and films did not kill live music. In the end, the impact of AI on your art and your practice comes down to choice.

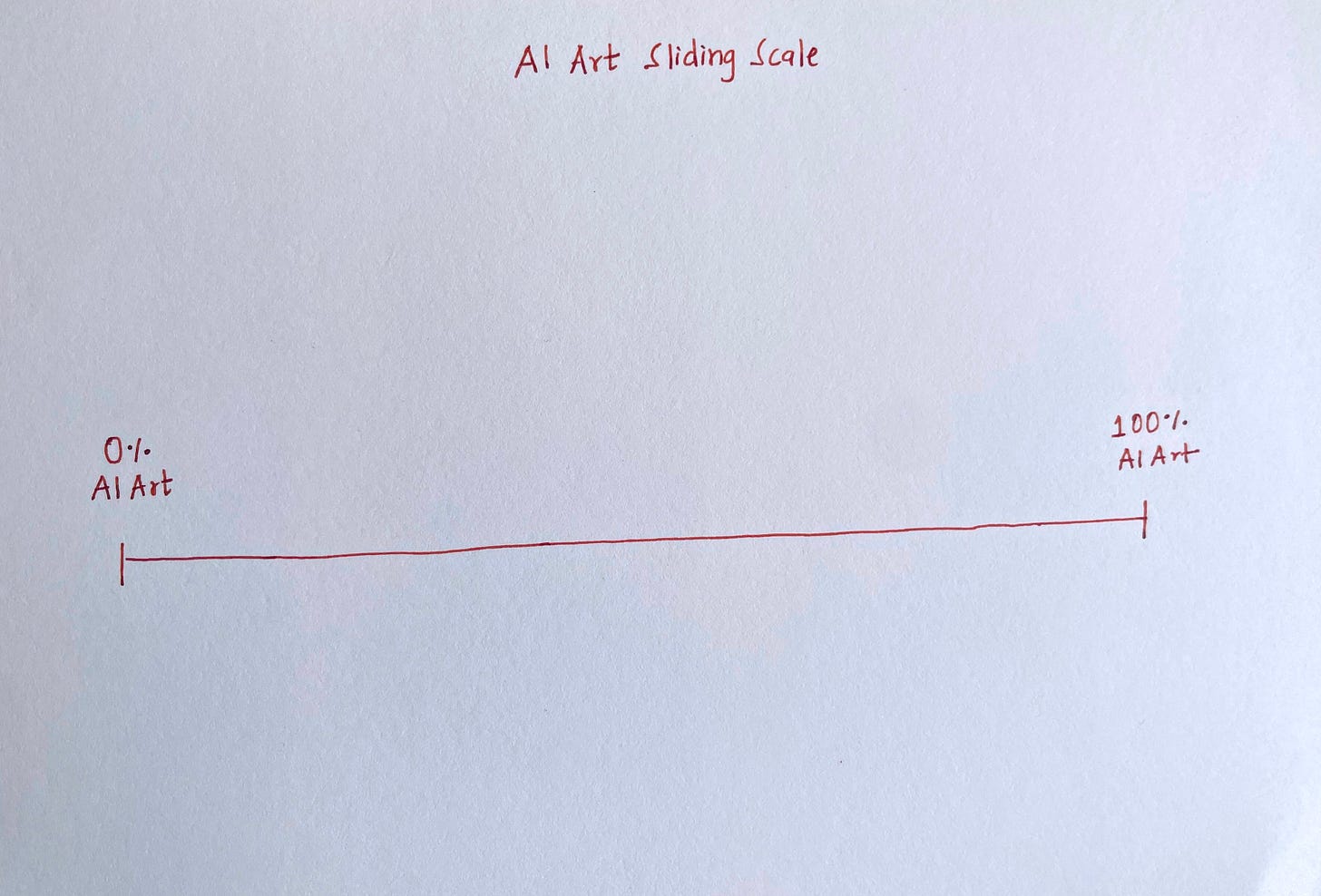

Find your place on the AI art sliding scale

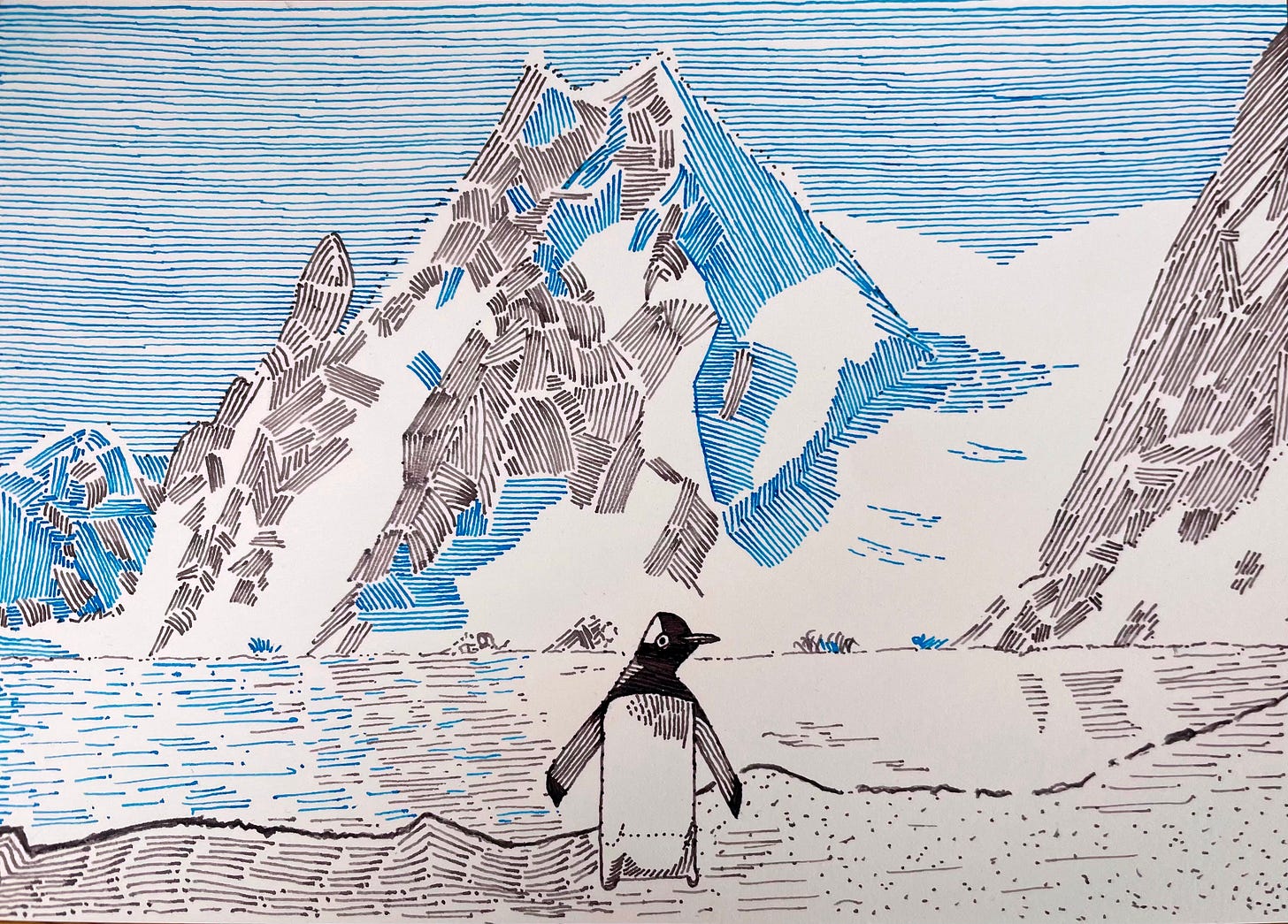

Consider a scale where your art varies from being 0% AI (like the sketches and watercolours you see in this piece) to 100% AI (Please point me to good references, I would sincerely love to see them).

What is your comfort? Both ethically (since LLMs are using art created by other people for profit), and functionally (AI as an editor / first draft writer / mood board creator, etc)? Many of us are already using AI knowingly or unknowingly (think spellchecks, digital art tools, etc), so the question is

What is the overt ‘AI as a tool’ choice you are making, and how much does it define your art?

Only you can answer this for yourself. I lean heavily towards the left side of this scale: I enjoy the messiness of learning new forms, love the friction of a fountain pen on paper, the fascination with the power of water in watercolours, and the joy of bringing together stories from different worlds in my writing, digging into contemporary and out of print books, conversations and collaborations with other artists, deepening my knowledge of mathematics - all in the service of finding the joy and satisfaction of creation in my life. I do use a couple of AI tools to fact-check the stories I present here and find credible references, especially books about niche subjects, which I can then buy and read at leisure.

Make the effort to find your answer.

Use AI to expand the scope of your art, not diminish it

If your answer to the previous question is to overtly use AI tools in your work, this is for you.

Anu Atluru has a wonderful interview with Neal Agarwal, the indie game artisan behind Neal.fun, a cult-favorite corner of the internet, home to weird, delightful, wildly viral games like The Password Game and Infinite Craft.

Neal says

For me, making games is about creative expression. I want to try to add something new and interesting to the world. AI tools are cool, but I’m not as interested in just making things cheaper and faster. The thing that excites me more about AI is when you can make something you couldn’t make before.

Use AI to grow as an artist, not as an excuse to shun practice.

Discover and cultivate your style

Sneaky Artist, Nishant Jain, said it best

Style is an accumulation of mistakes and the ideas that emerge from dealing with them. To get there, you have to spend time with your mistakes.

Quoting the acclaimed jazz musician Miles Davis

“Once is a mistake. Twice is an idea. Three times is style.”

In the age of virtual reproduction, what will make you stand out is your style. Think about any artist you admire, contemporary or otherwise, and ask yourself why you admire them. Chances are, it will be something about their style - a unique worldview, perspective, treatment or methods they employ. In the age of AI, your style will allow you to survive thrive. If everyone has access to AI tools for art, they are all using the same tools, minus any distinctive style of their own.

Your style is the unmodelable edge. Make the effort to find your style.

Arrive at your personal definition of art

Explaining mathematics with cats, thinking and writing about life’s questions as a millennial, sketching, watercolouring and whatever next excites me is why and how I do art. I chase my curiosities, bringing them all together into long-form writing. Foremost, I want my art to be a reflection of who I am as a person, I want it to be an exploration of curiosities, and I want it to be a documentation of the journey of my becoming.

No single artist or tech giant can define it for me. I want to continue to be the messy individual that I am, a forever work in progress, and not a sanitised pattern generation machine.

Find your personal definition, and then immerse yourself in the practice of your art.

Thank you for reading this far. I am grateful that you gave me 40 minutes of your time. I hope some part of this made you feel heard or helped you feel, think and live better.

I have one last thing to say. I, along with a friend, Deepak Gopalakrishnan (whose inputs found their way into this essay), run The 6% Club, a content creation program designed for people with full-time jobs. We help you launch your newsletter, podcast or YouTube channel in 45 days. We neither promise virality nor algorithm hacking, but a sustainable, enjoyable way to build a creative outlet for yourself. We have helped about 200 people so far with ideation, process + structure and accountability and could help you too.

.png)