I don’t personally care for protein powder or shakes, but what I do care for is accurate science reporting on lead contamination. Yesterday, Consumer Reports dropped a doozy of an investigative piece on lead levels in protein powders, and immediately captured online discourse. People who rely on protein drinks bemoaned their consumption of toxic metal content, and people who make fun of people who rely on protein drinks celebrated that they always knew that Huel was spiritually bad. I’ve written about lead remediation in scientific journals, and know more than a bit about heavy metal quantification. That is to say, I knew enough to quickly tell that CR was completely wrong here.

I’ve written before on the way that the media reports on scientific findings about contaminants in food and beverage products. It tends to be extremely misleading, and this wave of coverage was no exception.

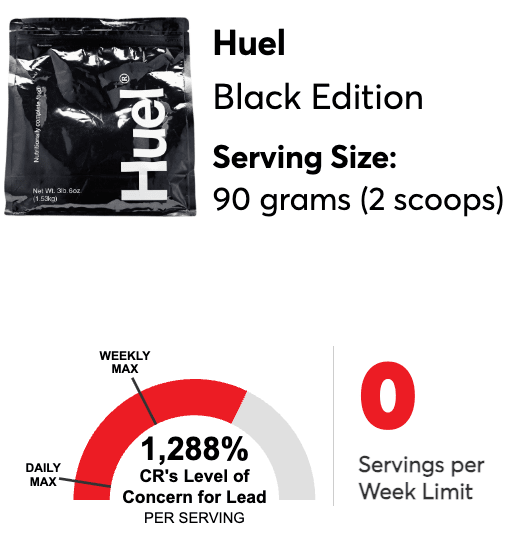

CR tested a range of protein powders and drinks, quantified the lead levels in them, and concluded that “two-thirds of them contain more lead in a single serving than our experts say is safe to have in a day.”

They also released some alarming graphics, clearly with implication that the public should stop consuming certain protein drinks.

Unfortunately, in this analysis they made multiple compounding errors, rendering their conclusion completely incorrect. I’m going to break this down for you, starting with the most heinous and obvious error and working my way into less heinous and obvious errors.

The value they’re using, when they say that these products contain more lead than the “experts say” is safe to have in a day, is from California’s infamous Prop 65.

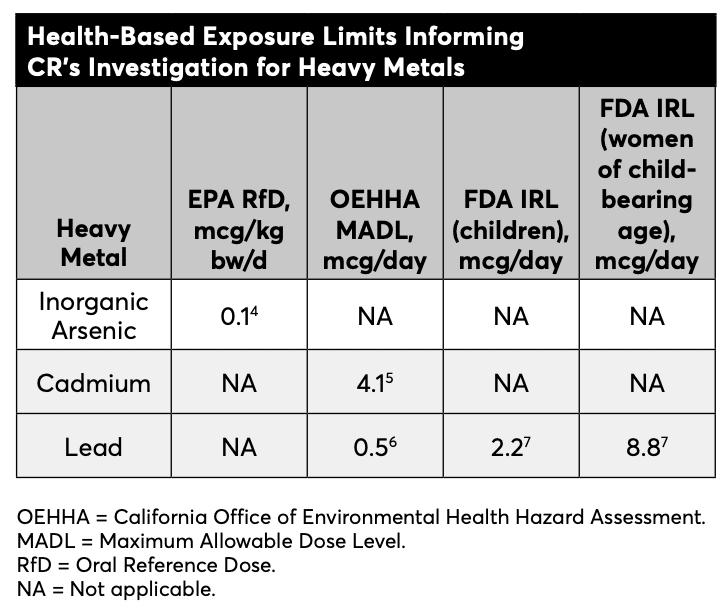

Notice a difference between the OEHHA’s 0.5 mcg (that’s MICROgrams, not milligrams, by the way), and the 2.2 mcg FDA recommendation for children, in the table below? Well, it’s 4.4x times lower, and it’s not like FDA’s recommendation for children is some sort of super lax guideline that needed to be tightened up. In fact, these levels were already tightened up as of 2022, from previous levels that were even higher. California’s guidelines are also 17.6x lower than the guidelines for (potentially) pregnant mothers that are often wrongly extrapolated to all adults, and if there were FDA guidelines for all adults, they’d probably be another factor of 4-ish higher, if I had to make a prediction.

As the CR investigation puts it:

This level is based on the California Prop 65 maximum allowable dose level (MADL) for lead—0.5 micrograms per day—which has a wide safety margin built in. “We use this value because it is the most protective lead standard available,” says Sana Mujahid, PhD, who oversees food safety research and testing at CR. “There is no safe amount of lead, and we think your exposure to it in the food and water supply should be as low as possible.”

This is completely insane. By the logic of there being “no safe amount of lead,” then we shouldn’t eat or drink anything. There are trace amounts of lead in all the food and water you drink, and there’s no way to avoid consuming minuscule amounts. Yes, of course we should strive to minimize the amount of lead we consume, but there are tradeoffs. At a certain low level, the tradeoffs in obsessing over and avoiding wide swathes of food products means that we may have to eat less healthily or spend too much time devoted to nutrition research at the expense of other parts of our health. For one, the stress in avoiding parts-per-trillion doses of lead is likely far worse for your health than the lead itself!

But even the FDA guidelines are lower than what is totally safe for normal adults! It would be one thing if CR had titled the article “young children and pregnant mothers might want to avoid consuming multiple protein drinks per day,” but that’s not the framing they went with. CR cites an expert who says that the FDA guidance of 8.8 mcg/day for women of child-rearing age (obstensibly due to the fact that they could become pregnant and the child could have elevated lead levels) is reasonable to apply to the general population. This is something that has been used for convenience by nutritionists and scientists, in the absence of a regulatory limit for adults. It is not scientifically meaningful, and I don’t think it’s a reasonable way for adults to think about the risk of consuming food with trace lead in it.

There’s a reason that most guidance focuses on children’s lead exposure. Children are at way more risk from heavy metal toxicity, due to its effect on their developing brains and bodies. Adults need to be worried approximately an order of magnitude less about their lead exposure than kids do.

After all this, if you are still inclined to give any credence to California’s Prop 65 values of 0.5 mcg/day, perhaps you would change your mind upon learning that the average real life, daily exposure for adults is about 10 times higher than this “Maximum Allowable Dose Level.” That is not to say that lead exposure isn’t concerning, nor that it wouldn’t be good if the population consumed less lead. But rather, that anyone attempting to quantify whether a product is safe or not on that threshold is likely to conclude that almost any food product is liable to be unsafe.

So, we’ve established that CR is using “levels of concern” for lead that are at least 17x too low, and potentially something like 80x too low. Thus, even the products that scored the worst in their experiments are still below the daily limit, if you consume one shake per day. One serving of Huel per day, which they say is 1288% of their level of concern, would actually be below the FDA’s guidance for pregnant mothers.

Okay, but I can already see what you’re going to ask next. If one serving is just below the level of concern, what if you’re consuming half a dozen protein shakes per day? What if you’ve totally replaced your diet with something like Huel, and you’re consuming 4000 calories per day because you’re bulking or training or something (I don’t know much about weightlifting if you can’t tell).

Apart from the fact that this is probably bad for several other reasons more concerning than lead levels, CR doesn’t provide a control. How much lead does a typical high protein diet contain? What are these protein shakes replacing? Also, some of these protein shakes are made by mixing powder with water. How much lead is just in the tap water you’re putting into the shake?

As CR mentioned, lower in their article, the EPA’s “action level” for tap water is 15 parts per billion (mcg/L), or about 1500% of CR’s “daily limit” in a single 500mL bottle of water. Of course, most tap water isn’t quite that high, but when I tested my building’s tap water at the last place I lived, it was around 2-3ppb, still well above the daily limit in just a single glass of water. And this is not a concerning value. It’s in fact below the FDA’s regulatory limit on lead in bottled water (5 ppb). I don’t think there’s a conspiracy by the FDA and EPA to allow Americans to consume unsafe amounts of lead by setting super high legal limits. For example, in Flint, Michigan, lead levels soared as high as 1 part per million, about 200 times higher than the bottled water limit. And even these measured values were bad mostly because they implied that sometimes the levels could be even higher than measured in rare cases, and because many children were drinking this water.

The CR article also didn’t provide lead levels for the kinds of high-protein foods that might be consumed as an alternative to protein powder. Protein shakes and powders are, by nature, going to have higher amounts of lead per mass than other foods, because they are highly densified sources of calories and protein. Imagine if I took a head of lettuce, boiled away all the water and condensed it into a powder. Well, that powder will have the same amount of lead in it as the lettuce from whence it came, in a much smaller mass. Is this noteworthy? No. It would in fact be noteworthy if the lead had transmuted into gold during this process, but the fact that lead remains unchanged when you evaporate water out of a food product is just basic physics.

While the previous two mistakes likely had a much larger effect on the communication of lead levels by CR, measurement error alone is enough to sink their analysis.

I previously discussed this as it relates to the measurement of plastic-related chemicals in food products, but there are several sources of compounding measurement error in detecting trace contaminants.

CR used inductively coupled plasma - mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to measure lead. I spent approximately one bajillion hours doing exactly this in graduate school, and can tell you with authority that these kinds of measurements are highly variable, are quite difficult to do well, and I’m highly skeptical of CR’s values.

For one, they provide no error bars. There are several types of error in these measurements. The largest source of error will be sample-to-sample error. CR says they tested “two or three" samples for each product. When they report a value of 2 mcg / serving, is this because they averaged two values of 3.8 mcg and 0.2 mcg? We have no error bars, so it’s hard to say. There’s also instrumental error. The ICP-MS will report the inherent error in the measurement. Depending on the instrument and the conditions of operation, this could be quite high. Finally, there’s also error that could be introduced in their sample preparation, which wouldn’t be easily determinable. Since CR isn’t reporting very basic things like this, I’m not sure I have confidence in their (or the lab they contracted) sample preparation techniques to avoid contamination with trace amounts of lead and other elements.

There’s a lot of noise in these sorts of experiments. One protein shake that has 5 mcg of Pb might not be statistically significantly distinct from another protein shake that has 1 mcg of Pb.

For example, imagine that there are two identical protein powders made from pea extract. Let’s say that in every 20 batches of pea plants, 1 of them has slightly higher lead levels due to soil variation. Well, if I test three samples each from these two identical powders, there’s some chance that one of my samples is from a batch with slightly higher lead levels. So, let’s say of these six samples, I measure 1 mcg, 1 mcg, 1 mcg, 1 mcg, 13 mcg, and 1 mcg. You can hopefully see how this might be a problem with these small sample sizes.

That leads into the next error that undermines CR’s reporting: data dredging / p-hacking / sampling bias of some sort / whatever you want to call it.

If you get dozens of products and test them all for a dozen contaminants, you’re going to find at least a couple that by random chance appear to have higher levels of one contaminant. This is the same bias that underlies the scientific reproducibility crisis.

Is Huel really worse than Muscle Milk as far as lead contamination is concerned, or did the two samples that CR tested from some given batch just have randomly higher levels of lead by chance? Because I would guess that many, many readers of CR’s reporting will read the article and switch from Huel to another product as a result. CR’s experiment is not powered to make that kind of conclusion, and they are unfortunately misinforming their readers.

On top of that, CR has been testing products like this for years. This would be a very good public service, if they would just honestly report their findings and not try to frame every single product class as having alarming levels of some contaminant. But “protein shakes have pretty benign levels of lead but maybe babies shouldn’t drink 5 per day” doesn’t make for a good article that gets millions of views. You have to imagine that if CR tests a range of products and doesn’t find high levels of contaminants, they probably don’t run the story. So, that introduces a second meta-level of data dredging concerns to their findings (they only report the studies that, perhaps by chance, have a couple products with “alarming” amounts of some contaminant).

Finally, the last issue with CR’s investigative report is that they transparently are against protein supplements. I have no horse in this race, but as I understand it, it’s very much an open debate in nutrition science as to whether supplementing protein can have positive health effects, and in particular can have utility for people who do weightlifting.

CR repeatedly uses language like:

We advise against daily use for most protein powders, since many have high levels of heavy metals and none are necessary to hit your protein goals.

…and:

Supplements in particular are often not worth the risk, especially if they haven’t been recommended by a doctor, she says. “Why take in unnecessary lead with protein powder?”

Imagine a similar article about coffee or chocolate, two other products that sometimes have slightly elevated levels of heavy metals (again, nothing to be concerned about) if you go and test 100 different chocolate bars or something. It would seem extremely paternalistic for CR to offer guidance on whether consumers enjoy coffee products. Many people derive a ton of enjoyment from drinking coffee, and for CR to say “any amount of additional lead outweighs any benefit from drinking coffee,” would be just as absurd as what they’re saying for protein shakes.

It’s bad when scientists have preconceived notions as to the morality of what they are studying, and CR shouldn’t try to litigate whether or not protein powder is “good” or “bad” for you in this underhanded manner. If they want to make an argument on the health benefits of protein supplements, they should do so. But just quoting “experts” as saying that protein supplements are unnecessary does not add value to the debate, and using spurious metal toxicity findings to cast aspersions on the entire field of products is even worse, especially given that CR found that many protein supplements have very safe levels of lead. This of course should also be taken with a grain of salt, given the issues I’ve already highlighted.

The damage is unfortunately already done, from the perspective of Huel and other protein shake companies.

Basically every major publication, including the New York Times, has reported on this in a fairly credulous manner:

Experts who were not involved with the testing expressed concern about its findings. Dr. Stephen Luby, a professor of medicine at Stanford University, said the results were “very troubling.” Dr. Pieter Cohen, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, called them worrisome as well, though he cautioned against using the report “as a purchasing guide.”

I worry about these “experts” sometimes. I worry that they are unable to critically examine scientific findings in a public-facing way. I worry that they will basically say to journalists whatever they think will increase the perceived importance of their subfield. I myself have been interviewed by journalists about my research and the research of others, and it’s genuinely hard to push back against the narrative that you are presented with, especially if you’re just happy to have a fancy journalist—whose writing you might even be a fan of—interviewing you.

Of course, it doesn’t make for a fun article to present the opinions of scientists saying things like “well, they didn’t include error bars.” But I hope you think it makes for a fun BS Detector blog post. Relax, lean back, and drink some Huel.

.png)