If there is a pantheon of Doomsday Men, one of those who deserves to be in it is General Curtis E. LeMay. Very few individuals did as much for both molding and embodying the structure of nuclear apocalypse as did LeMay.

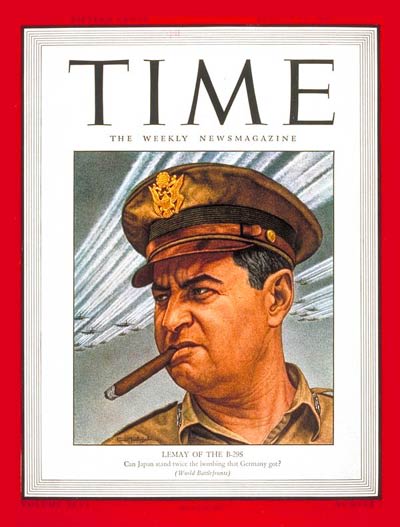

LeMay has always given me the creeps. His deeds are bad enough — we’ll come to those in a moment — but his entire affect is, in a word, reptilian. If the eyes are the windows into the soul, there’s a certain deadness reflected in every photograph of LeMay that I’ve seen. I thought that for years, before I learned that there was an additional dimension: that his unsmiling appearance was literally pathological, a result of having developed Bell’s palsy during his city-bombing campaigns of World War II, which left him unable to project happiness. There’s something almost Dickensian about that fact.

LeMay was the quintessential bomber-engineer. His reputation was as someone who demanded efficiency above all else, and the subject that he put his efforts towards was mass destruction. There are other more Strangelovian generals out there — but he’s really almost beyond parody.

If I extolled all of LeMay’s biographical details here, it would be too much to read. He was the architect of the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. He considered his actions to be indistinguishable from those of a war criminal, and did them anyway. He bragged that he out-did the Nazis for bombing cities by far.

He created the Strategic Air Command and turned it into the most effective and efficient organization for planning and executing the mass destruction of civilian populations that the world has ever seen. At its height he probably held the capability to kill half a billion people almost overnight. Worried that World War III might break out and the President might not be able to — or might not be willing to — give the orders to unleash that hell, LeMay worked out, during the Truman administration, protocols by which he could just seize the weapons illegally. This is a fact he later talked about openly, and can be corroborated with documentary evidence from the time. (I talk about these aspects of LeMay in my forthcoming book, which is available for pre-ordering now...)

What I really want to dwell on here, though, is a book that LeMay published in 1965, co-written with MacKinlay Kantor, called Mission with LeMay: My Story. It’s billed as a memoir, but that feels insufficient as a description. It is more like a drunken oral history, with almost no attempt by LeMay (or Kantor) to make coherent its stream of consciousness rambling.

Here’s how he talks about the firebombing of Tokyo, for example:

…Again it’s an April morning twenty-nine months later (strangely enough. Let the numerologists look into this one: instead of B-17’s we are using B-29’s). The place is the limestone-and-coral isle of Guam instead of a tired bomber base on the Bedfordshire-Northants border in England. And I’ve been pounding that floor until my feet are ready to crack at the ankles. But good news is beginning to mount up. ...Here comes Tommy Power — he’s stooged around for two hours after completing his bomb run, taking pictures of the destruction of Tokyo. We will examine those photos while they’re still wet. We have never seriously wounded the largest city in the world before, but this time— In a few hours, and operating from the seemingly suicidal altitude of only five to seven thousand feet, we have burnt the belly out of Tokyo. We know that we have shortened the war by many months. Each of those fourteen crews who went down on that mission have saved American lives, perhaps by the scores of thousands. We don’t pause to shed any tears for uncounted hordes of Japanese who lie charred in that acrid-smelling rubble. The smell of Pearl Harbor fires is too persistent in our own nostrils.

I want to emphasize that I have not edited any of the above whatsoever. The ellipses, the dangling hyphens, the strange punctuation, that is all directly from the original. Just bizarre.

If you pick up Mission to LeMay and open it to almost any page, you find just unfiltered, stream-of-consciousness madness. William Burroughs couldn’t do better. Here’s LeMay talking about the nuclear firepower of a Convair B-58 “Hustler” bomber (again, unedited):

And in that beautiful devilish pod underneath, the baby of the fuselage—half-size, but still of the same shape and sharpness, clinging as a fierce child against its mother’s belly — the B-58 carries all the conventional bomb explosive force of World War II and everything which came before. A single B-58 can do that.

It lugs the flame and misery of attacks on London ... rubble of Coventry and the rubble of Plymouth. ... Blow up or bum up fifty-three per cent of Hamburg’s buildings, and sixty per cent of the port installations, and kill fifty thousand people into the bargain. Mutilate and lay waste the Polish cities and the Dutch cities, the Warsaws and the Rotterdams. Shatter and fry Essen and Dortmund and Gelsenkirchen, and every other town in the Ruhr. Shatter the city of Berlin. Do what the Japanese did to us at Pearl, and what we did to the Japanese at Osaka and Yokohama and Nagoya. And explode Japanese industry with a flash of magnesium, and make the canals boil around bloated bodies of the people. Do Tokyo over again.

The force of all these, in a single pod.

And LeMay apparently didn’t even like the B-58, because its range was so limited. The above is how he talks about a bomber he doesn’t particularly care for.

Imagine yourself at a bar, and a heavyset, dead-eyed man who is physically incapable of smiling started in with that rant. I’d almost rather have a drink with Cormac McCarthy’s Judge Holden from Blood Meridian, I think.

Here’s LeMay riffing on the Strategic Air Command (again, unedited):

The B-58 was and is symbolic of SAC, as is the B-52, as could be the B-70 if we had them standing on the line (where they should be standing this minute. Maybe their advanced prototypes will stand there in the future).

If you removed that plate from the body of SAC, you could look in and see people and instruments. They would be as the intricate electronic physiology of an airplane today: each functioning, each trained, each knowing his special part and job — knowing what he must do in his groove and place to keep the body alive, the blood circulating. Every man a coupling or a tube; every organization a rampart of transistors, battery of condensers. All rubbed up, no corrosion. Alert.

“Peace is our profession,” say the folks in SAC. Couldn’t be more correct, either.

There is a sequence about LeMay and the firebombing in Errol Morris’ The Fog of War (2003) that is just worth watching if you have not seen it. The film as a whole, which is an extended interview with former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, is itself a must-see, but this sequence in particular, in which McNamara discusses what it was like to work as an aide to LeMay during World War II, what he was like as a person, and the question of whether they were “behaving as war criminals”:

Out of all of the parts of Mission with LeMay, though, the most telling part, I think, is the final paragraph of the introduction, in which he addresses his feelings about the bombing of Japanese cities. Here it is in its entirety:

I have indeed bombed a number of specific targets. They were military targets on which the attack was, in my opinion, justified morally. I’ve tried to stay away from hospitals, prison camps, orphan asylums, nunneries and dog kennels. I have sought to slaughter as few civilians as possible.

What can one say to such callousness? It is strange even by the standards of his time and his contemporaries. “I have sought to slaughter as few civilians as possible.” What madness.

I don’t think LeMay came up with “Peace is our profession” as the motto of SAC, but it remains associated with him. When SAC was replaced by Strategic Command in 1992, they got rid of the motto. Years later, when General John Hyten became head of Strategic Command, he very deliberately worked to restore its “status” within the military, and part of that was bringing back the motto, but with one change. See if you can spot it:

Here’s Hyten explaining it during an address in 2018:

There’s one change that is made to that motto that you’ll see if you look carefully as you go around the command. The key is actually on that chart. Go all the way to the bottom, below my name. You see “Peace is our profession”, right? But if you notice the little thing at the end, because the legend has it that Gen. Curtis LeMay back in the 1950s when he heard that motto said. “I really like that motto. That’s who we are and that’s what we do. But you know what? You need a dot, dot, dot at the end." The dot, dot, dot at the end says peace is our profession, however, if you want to cross the line, we’re coming.” And we’re coming in the most unbelievable, powerful way and we will change the game, and you never want to cross that line.

And so that’s the change: the addition of the ellipses (…). I think LeMay would have approved, but I’m not sure that’s a good thing.

.png)