Untold Stories of American History

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Charles Oldrieve used custom-made wooden shoes to float on the water’s surface and propel himself forward

October 30, 2025

:focal(750x500:751x501)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/02/b0/02b0ad5f-1007-4a21-ba98-1d65dc4b4f14/oldrieve.png)

For the past 35 years, dozens of students have walked across Florida International University’s campus lake every November as part of the school’s Walk on Water contest, which is believed to be the largest and longest-running competition of its kind in the United States. Architecture professor Jaime Canavés started the contest as a fun design challenge for students, who build their own floatable shoes, then race each other across the lake. (Though the event won’t take place this year, Canavés hopes to bring it back in 2026.) In the late 1800s and early 1900s, however, walking on water was a more serious enterprise. Large crowds gathered to watch performers who walked through knee-high waves and “skipped about on the surface of the water with the ease of a ballet dancer,” in the words of one New York City newspaper.

Of these daredevils, arguably none was more successful or adventurous than Charles W. Oldrieve, a former tightrope walker from Boston. While other “aquatic pedestrians,” as they were sometimes called, mostly gave short demonstrations, Oldrieve used his oversized, wooden, canoe-shaped shoes to cover long distances. In November 1888, when he was 20 years old, he walked more than 150 miles down the Hudson River, from Albany, New York, to Manhattan. The journey lasted six days and involved water temperatures so cold that one night, when Oldrieve came ashore to sleep (he only walked during the day), his shoes were covered in ice.

A year later, Oldrieve announced plans to walk across the English Channel, and in 1898, he said he was going to walk across the Atlantic Ocean. Neither plan came to fruition, but Oldrieve completed other feats, including walking across waterfalls and to islands off the Boston coast. His tightrope balancing skills likely gave him an advantage, but his assured, steady gait probably helped him the most. “Usually, floating is fairly easy,” says Canavés, who has watched hundreds of students learn to walk on water shoes over the years. “The biggest problem is to go forward. If you do not do something to create traction, you’re moving back and forth but staying in place.”

Oldrieve’s shoes had fins, or flappers, on the bottom. “When the foot is brought forward and the shoe forced through the water, [the fins] lay flat up against the bottom of the shoe until the step is taken, when they drop down and present a surface to press against the water,” the Boston Globe reported in 1889. “By their aid, the walker is able to move forward, for without these little flappers, he could make no headway.”

Oldrieve’s shoes were similar to those worn by other water walkers, but he experimented with different designs over time and continually worked on his technique. By the early 1900s, he could not only walk forward and backward in his shoes, but also turn around in a circle—a maneuver that he said took him five years to master.

Did you know? Walking on water

According to the National Park Service, at least 1,200 species have evolved to walk on water. Among the most famous is the water strider, an insect that uses surface tension to propel itself forward on the water’s surface.

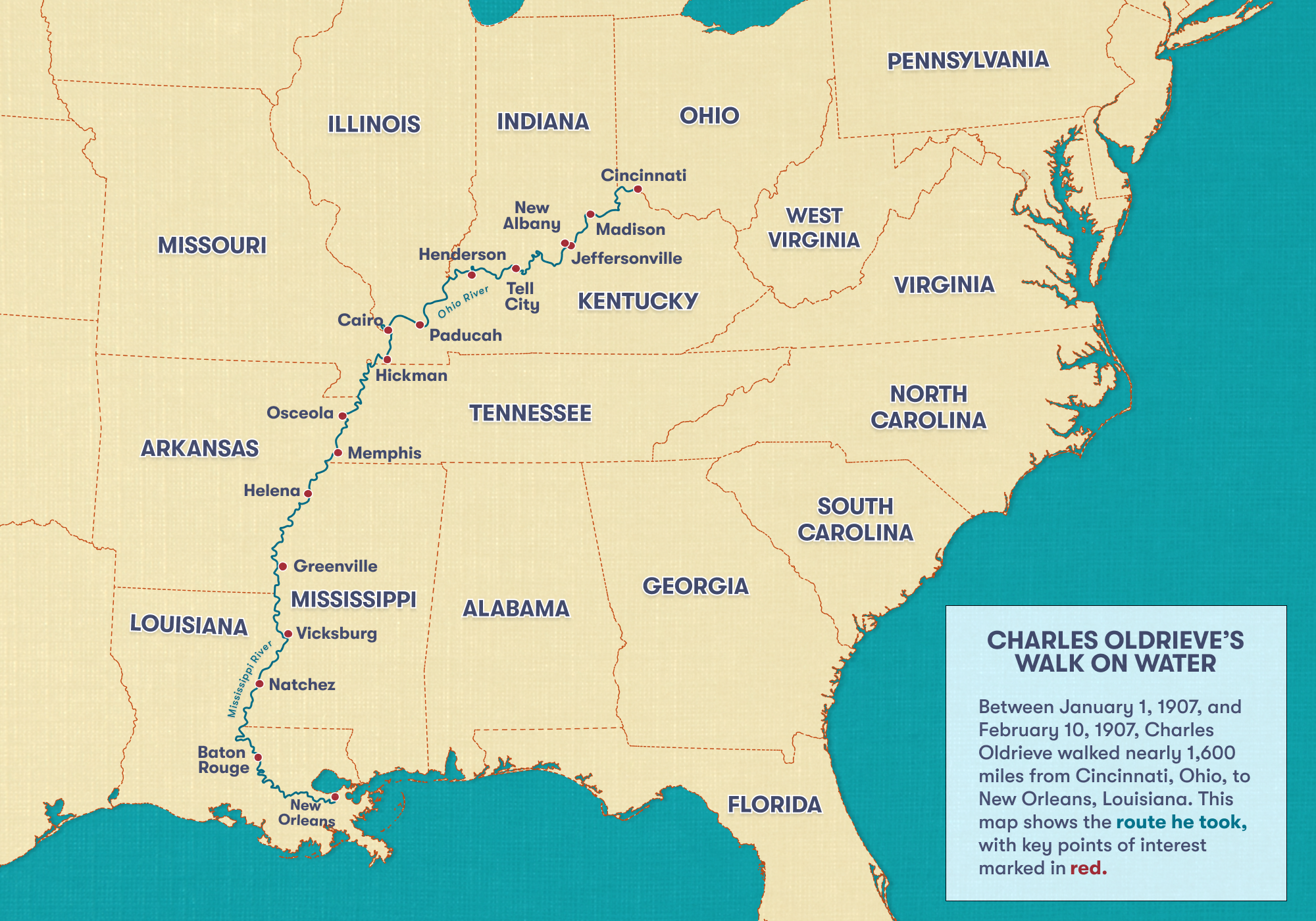

A map of Charles Oldrieve's route from Cincinnati to New Orleans / Illustration by Meilan Solly / Data from Newspapers.com

A map of Charles Oldrieve's route from Cincinnati to New Orleans / Illustration by Meilan Solly / Data from Newspapers.com

In January 1907, Oldrieve embarked on his most ambitious journey yet: walking down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, from Cincinnati to New Orleans. He began the nearly 1,600-mile trip on New Year’s Day, accompanied by a small gas-powered support boat and his wife, Caroline Oldrieve, who rowed alongside him in a skiff. His goal was to reach New Orleans in 40 days. If he succeeded, he told reporters, he would win a $5,000 wager.

Oldrieve could travel up to five miles an hour, depending on the river conditions, though he estimated his average speed was closer to two miles an hour. His shoes, which measured about four and a half feet long and weighed around 20 pounds each, generally required a slow pace. He also had to stop periodically to dump water out of his shoes despite wearing thigh-high rubber boots to keep them as dry as possible. When Oldrieve arrived in Henderson, Kentucky, on January 12, he was two days behind schedule. He didn’t seem bothered by the delay, however, and happily greeted the thousands of people waiting for him on the riverbank.

Although one Henderson resident was allegedly disappointed that Oldrieve wasn’t taller—he was at most 5-foot-3—the vast majority were excited to see him. After coming ashore to receive a telegram and “take a glass of stimulant,” Oldrieve showed the crowd his shoes, which, like his hair and mustache, were “red almost to scorching,” according to the local newspaper. He always acknowledged spectators in some way as he walked past, either by waving or smoking a cigar, and no one wanted to miss him. “At every town or city along the river, the wave walking party is being greeted by crowds which increase from day to day, as interest in the feat is awakened,” another newspaper reported.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/f9/cdf9abd9-db31-42df-9aad-81ac4d01012b/shoes.png) A newspaper article about Oldrieve's custom shoes

The Montreal Star via Newspapers.com

A newspaper article about Oldrieve's custom shoes

The Montreal Star via Newspapers.com

Oldrieve managed to get back on schedule once he reached the Mississippi River in Cairo, Illinois, but he was struggling physically. He complained of rheumatism in his back and came down with chills and a high fever. Still, the weather and river conditions favored him as he continued south. He arrived in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on February 6, several hours ahead of time, and said he expected “no trouble in reaching New Orleans.”

Navigating the river between Baton Rouge and New Orleans could be challenging, though, especially for small boats. “It’s a huge body of water, and the currents can be incredibly powerful,” says paddler Scott Miller, who led a team that set the world record for canoeing the length of the Mississippi in 2023. In the early 20th century, the lower Mississippi was full of large boats and barges, which Miller says “are probably the most threatening thing to small craft.” Oldrieve was nearly swept under a barge as he approached New Orleans and might have been killed had he not been rescued by some men on board. When he finally got to the city on February 10, about an hour ahead of his 40-day deadline, he was triumphant but exhausted. “I wouldn’t walk that river again for five times the money I won,” he said.

Oldrieve still wanted to walk across the English Channel and planned to do so that August, but his wife hoped he would quit after that. “I think my husband will retire after he has walked the English Channel,” she told the press. “That is the last thing I want him to do, and I would rather he did not do that.” In the meantime, the couple went back to performing, which was their main occupation when they weren’t attempting long-distance feats. Each show took place on the water and featured Oldrieve walking around on his shoes and setting off explosives to create “water geysers” and re-enact naval battles. Oldrieve had been starring in these types of performances since the 1880s, and Caroline had been assisting him with them for several years. In 1903, the pair got into trouble with Massachusetts fish and game officials when their explosions sent scores of fish flying into the air, but their performances were otherwise well received.

Episode 93: Mississippi Speed Record with Scott Miller

Oldrieve had allegedly won $5,000, the equivalent of more than $170,000 today, for completing the New Orleans walk, but he and Caroline seemed to be in no hurry to collect the sum, which was said to be waiting for them in a Boston bank. Later, Oldrieve claimed that his manager had swindled him out of the money, but it’s also possible that the wager wasn’t real. Wagers were a common feature of circus and vaudeville performances in the early 1900s, says Andrea Ringer, a labor historian at Tennessee State University and the author of Circus World: Roustabouts, Animals and the Work of Putting on the Big Show. “Acts also became stale really quickly,” she adds, leading performers to come up with different ways to sustain audience interest.

Most of Oldrieve’s earlier stunts, including the Hudson River walk, had involved wagers, too. Yet he never had much money, and he lived at his mother’s house in Boston even after he was married. Moreover, one of the men who supposedly owed Oldrieve $5,000 for completing the New Orleans walk on time—Edward Williams of Boston—had the same name as his stepfather. Regardless, Oldrieve seemed to enjoy performing and might have continued putting on shows no matter how much money he earned.

Oldrieve and Caroline spent the spring and early summer of 1907 performing in towns along the Mississippi River. The couple promoted themselves heavily. Caroline was billed as a “champion oarswoman,” though it was unclear which races she’d won, while Oldrieve called himself “the world’s champion water walker.” He also used titles, such as professor and captain, that he likely didn’t hold. An advertisement for the couple’s July 4, 1907, performance in Greenwood, Mississippi, promised “the greatest sensational attraction of the 20th century.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/a6/6ba667a4-2806-43ec-8b8f-1487bbe16bc8/the_commonwealth_1907_06_14_1.jpg) An advertisement for the Oldrieves' July 4, 1907, show

The Commonwealth via Newspapers.com

An advertisement for the Oldrieves' July 4, 1907, show

The Commonwealth via Newspapers.com

Sadly, that July 4 show wound up being the Oldrieves’ last. Caroline was badly burned while setting off explosives during the act and died from her injuries a few days later. Oldrieve, having been told that she would recover, was on his way to perform in Kentucky when he got the news. Devastated, he killed himself by drinking chloroform. He died penniless, according to the owner of the Memphis boarding house where he had been staying, and was buried in an unmarked grave at one of the city’s Catholic cemeteries.

Many members of the public found the circumstances of the Oldrieves’ deaths upsetting. “The lives of these two good people, and their unfortunate ending, afford food for thought and reflection,” wrote one newspaper columnist.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/21/53/21537124-13e5-4dab-a320-4484e699fd75/ledger_star_1932_05_05_5.jpg) Oldrieve's exploits, as featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not

Ripley's Believe It or Not / The Norfolk Ledger-Dispatch via Newspapers.com

Oldrieve's exploits, as featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not

Ripley's Believe It or Not / The Norfolk Ledger-Dispatch via Newspapers.com

In later decades, Oldrieve was best remembered for his New Orleans walk. In 1932, his journey was featured in Ripley’s Believe It or Not; in 1951, an Arkansas resident fondly recalled watching him walk past her town when she was a child. Although people continued to walk on water with various types of boat-like shoes well into the 20th century, none covered the kinds of long distances that Oldrieve had.

In 1978, an American Army sergeant named Walter Robinson realized Oldrieve’s dream of walking across the English Channel on custom-made water shoes. Ten years later, French musician Remy Bricka used long, rowboat-like shoes to walk across the Atlantic Ocean, setting a new world record. Both Robinson and Bricka propelled themselves forward with oars, however, whereas Oldrieve used only his shoes.

Whether Oldrieve would have made it across the rough waters of the Atlantic or the English Channel is impossible to know, but he seemed to value originality above completing specific journeys. “You see, I want to make a world’s record that shall never be beaten,” he said in 1898. With his Cincinnati-to-New Orleans walk, he appears to have achieved that goal.

.png)