“He drew the world. He did a portrait of the world. It doesn’t look like the world, but he drew a portrait, a landscape of the world as it operates. The world that we’re living in now, and the world that’s yet to come. We’re in Mark’s future. And his future is fucked up.” — Greg Stone, 2011

In the days after September 11, 2001, an FBI agent called the Whitney Museum of American Art. She wanted to come inspect a piece in their collection: a drawing by the artist Mark Lombardi, entitled “BCCI-ICIC & FAB, 1972-91”. In delicate arcs and nodes crisscrossing the large paper, it revealed the complex web of individuals, governments and regulatory interventions that led to the 1991 collapse of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, which was ripped open by a massive seven-country-wide sting operation and proven to be a veritable cornucopia of financial crimes. BCCI, set up by a Pakisani financier, was registered in Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands with offices in Karachi and London. Ten years after its founding it had metastasized into 78 countries, none of which had overall regulatory supervision over it. This was intentional. The bank set itself up as an opaque box obscuring the activities within, but Lombardi’s drawing opened the box and meticulously mapped the contents. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some of the names he listed were also connected to the financing of the 9/11 attacks. The FBI thought he might have uncovered connections they hadn’t made.

Lombardi spent almost seven years in the completion of the BCCI drawing (1994-2000): obsessively researching, compiling indices of names and relationships, detailing everything in an archive of cross-referenced index cards before he began sketching out the relationships on paper. There were arms dealers, drug traffickers, financial heavyweights, politicians of all stripes, the CIA, the NSA. “I call these narrative structures”, he said, “and I want to tell a detailed story. A story that perhaps has some dark passages to it.” In this story, the story of massive corruption on a vast, international scale, planned and improvised by all kinds of actors, we can see something fundamental about the way power moves in the world. Something Lombardi, on his own, using only data that was publicly available, had managed to make visible and legible: he had created maps of a territory the state itself had been unable to see.

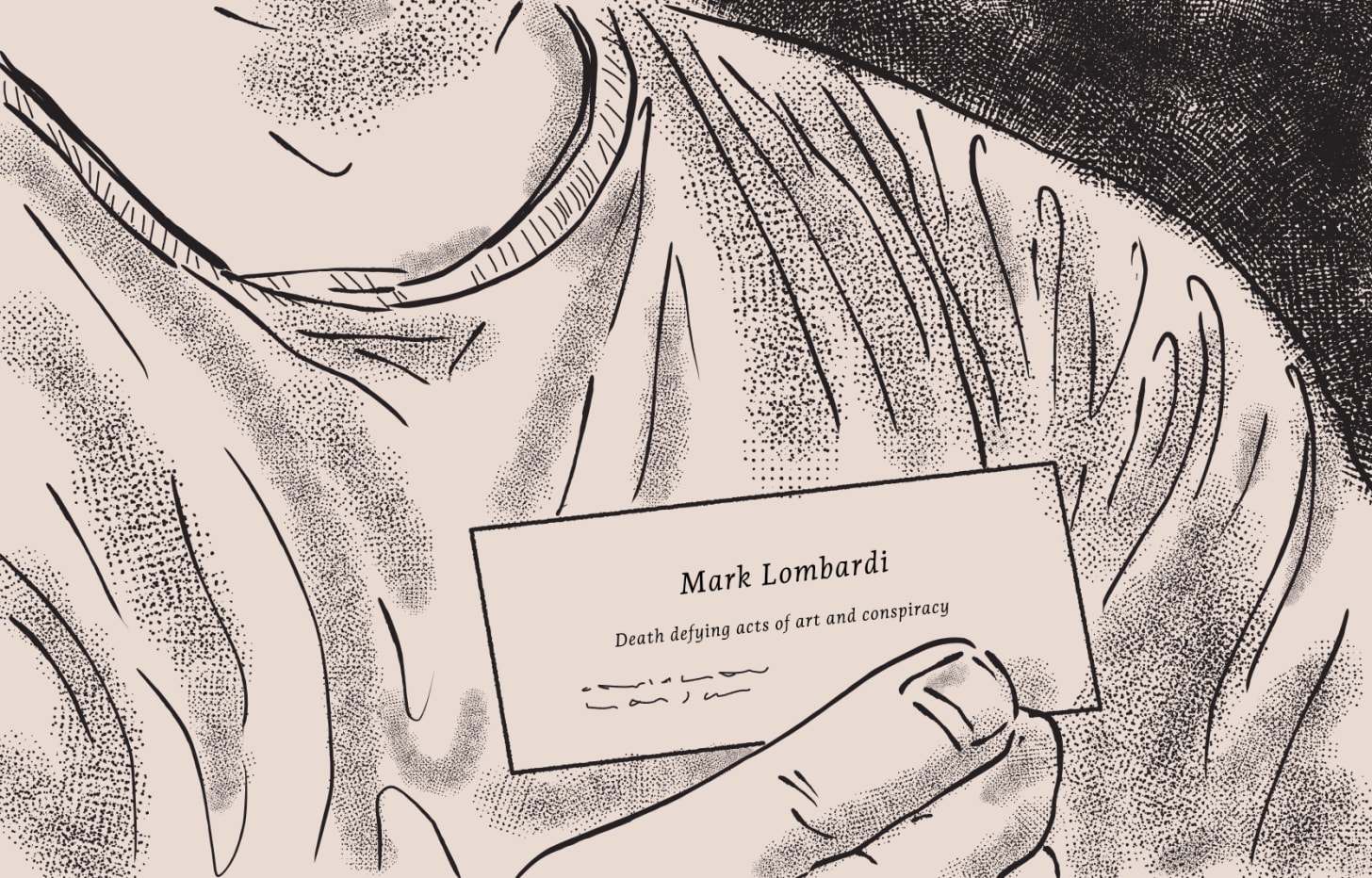

Perhaps under other circumstances the FBI would have wanted to interview him personally— the man his friend and fellow New York artist Greg Stone said in a 2011 documentary would “have to tell you he was an artist, because what he knew didn’t lead you to believe he was. He could have been someone who was very involved in politics, or in the banking industry, or an investigator for the FBI. He could have been any of those things, but he was actually an artist.” Stone holds a business card up to the camera. “So when he gave you his card, it didn’t necessarily mean ‘I’m an artist’, but that’s what he was.” The card, thick cream stock, slightly more rectangular than average, reads:

Mark Lombardi

Death-defying acts of art and conspiracy

In 2001, when the FBI called the Whitney to see his BCCI drawing, Lombardi was already dead by suicide.

I remember my first time seeing a Mark Lombardi drawing. It was at a party being given by his gallerist Joe Amrhein at Amrhein’s loft in Williamsburg, Brooklyn sometime around 2003. I have no idea how I got there— probably invited by someone tangentially connected to the gallery (Pierogi), which was located within walking distance of my tiny, grey apartment. I remember being struck by the warm, thin-boarded wood floors and high ceilings of the loft, and cowed by all of the art on the walls. Up high, on a mezzanine of sorts, was an intricate, confident drawing on cream-colored paper. It looked a bit like a complex solar system, or a very beautiful diagram of a circuit board. Up close, it was filled with names and notations, some familiar: George Bush (both of them), Ferdinand Marcos— many unfamiliar. On an intuitive level I understood the drawing as the product of both individual obsession and the desire to derive some order out what seemed to be chaos— the kind of chaos alternately undergirded and reinforced by malevolence. For all its elegant austerity the drawing felt powerful and weighty. “Who is this by?” I asked. “Mark Lombardi” my friend responded. “He killed himself recently.”

That drawing, his work, stuck with me, as did his death— the idea that an artist could distill artistic practice into insights valuable and potentially dangerous enough that they were sought out by federal investigators in times of national calamity, the idea that the weight of knowing enough detail might end up becoming too heavy because there was just too little to be done about it. Chisel out the information, architect the lines between, sculpt the narrative, only to have the same events keep happening over and over again. “When I see an Enron, or a Bernie Madoff, in my head I see a Mark Lombardi drawing”, Amrhein said in 2011.

Ultimately, what Lombardi made visible was what economic historian Immanuel Wallerstein theorized: the structural architecture of the capitalist world-economy depends on corruption as its load-bearing infrastructure. In 2025, as we pull up on what is likely yet another financial crisis, Lombardi’s methodology offers a way to understand how offshore finance, shadow banking, and cryptocurrency thrive through the deliberate production of ‘illegible zones’ that resist any kind of state oversight or regulation. Per Wallerstein, we should reject the individual country as the primary way of understanding capitalism and view the world-economy (hyphenated to show its unity) as a single, interlinked system featuring a hierarchical division of labor among countries. Core states with capital-intensive production and high wages (like the US) extract raw materials and cheap labor from states on the periphery (like those in Africa and Southeast Asia). Semi-periphery states (like Mexico and India) exist in the buffer between, concentrating systemic tensions and vying for core status. States aren’t autonomous sovereigns but are defined through their position relative to one another and to the system as a whole.

Strong states impose rules (trade, military support, visas and immigration, etc) on weak states, which mutually constrain both. The core states reinforce their relative strength by engaging in extractive, even abusive, unequal exchange with the periphery and semi-periphery, and the interstate system maintains this structure through official relations and financial channels while regulating (or appearing to regulate) capital, commodities, and labor. We could say this is the smooth surface of late stage capitalism that maintains the appearance of stability, but under the skin there is tense and potentially disruptive energy. Because this energy needs somewhere to go, we get zones of structural illegibility: offshore banking havens, unregulated or lightly regulated markets, shadow banks and institutions, and black or grey markets of all kinds.

All of these are deliberately produced (or at least tolerated) regulatory voids that function as heat sinks for the world-economy: they act as buffers absorbing risky financial flows, illicit capital, and speculative practices that would generate systemic instability or regulatory scrutiny if carried out in core jurisdictions. By providing secrecy, legal opacity, and trans-jurisdictional arbitrage opportunities, these zones allow the core financial system to maintain apparent stability while allowing risky or destabilizing activities to “dissipate” in a theoretically contained environment. Which is not to understate their risks or detriments to the vast majority of citizens: every scandal or major financial crisis involves the visible, legible parts of the system and the hidden, illegible parts getting caught in a negative, self-reinforcing feedback loop, which eventually builds enough pressure to break the system’s skin (see: 2008).

It was anthropologist James C. Scott who theorized that modern states require legibility in order to govern: complex social realities must become visible, simplified, and flattened in order to be controllable. Without an enhanced degree of standardization, states cannot know who is whom, who owns what or lives where, making taxation, public services, and shared infrastructure impossible. Offshore jurisdictions invert this— they evade transparency, taxes, and regulation while paradoxically remaining wholly dependent on state enforcement of private property rights and contract laws. This is power executed via strategic withdrawal of state oversight; the purposeful creation of blind spots that exist, in economist Ronan Palan’s formulation “elsewhere, ideally nowhere”.

At this point we might ask whether this kind of system corresponds to a larger pattern, and what the rapid rise of and market domination by illegible zones says about the state of the world-economy in 2025. Economist Giovanni Arrighi traced the large cycles that make and break powerful core states since the 18th century and noted two distinct forms: productive growth cycles (which he termed M-C) and speculation cycles (which he termed C-M’). Productive growth cycles are characterized by a growing core state investing money in making things, building infrastructure, and trading those things with other states. The new core state is so successful at doing this that it inspires semi-peripheral states to do the same, thus the world-economy slowly becomes more competitive and less profitable for the core (the paradox of late capitalism). Speculative cycles, in contrast, feature profit from past successful thing-selling and thing-building being siphoned into more and more archaic financial instruments (read: high brow gambling) in more and more opaque institutions and jurisdictions. Instead of making and building things, businesses and the wealthy try to make money from money. It is not shocking to realize that speculative cycles are associated with decline, and the financial crises associated with rampant speculation tend to accelerate it once begun.

In late 2025, we are already deep into a speculative cycle that began in the 1970s, when excess US capital first began sloshing into the global financial markets. Since that point we’ve seen many BCCI-esque scandals and collapses, each seemingly larger and more interconnected than the last. With the arrival of the second Trump administration the pattern has taken on a nigh-farcical level of mundanity, from the casual acceptance as ‘fact’ that the ultimate value of anything (including humans) is determined by financial profitability, to the feverish proliferation of illegible zones— from shadow banks, to freeports, to cryptocurrencies, to (apparently) US Presidential emoluments. As of this writing, it is estimated that the shadow banking sector alone accounts for around 50% of total global financial assets (the same size as if not larger than the regulated banking sector), and between 12-30% of all wealth is held in offshore jurisdictions.

Donald Trump, being the avatar of both speculation and structural decline, has naturally spun out hundreds if not thousands of scandals and scandals-in-waiting, as have his dutiful lackeys and hangers-on. Undoubtedly quite a few of these are about to blow up, from the recent discovery of $2 trillion in heavily leveraged US Treasuries held by hedge funds in the Caymans (apparently the only entities eager to buy up wobbly US debt), to the Trump family’s UAE-backed stablecoin empire. No one yet knows what the collateral damage will be when the system fails yet again and all the accounts are tallied. While there is much incipient tragedy in all of this, one of the small darknesses is that Mark Lombardi is not here to chronicle it: to frenziedly research it, scribble it on index cards, and meticulously spin it into gorgeously legible, if incalculably heavy webs.

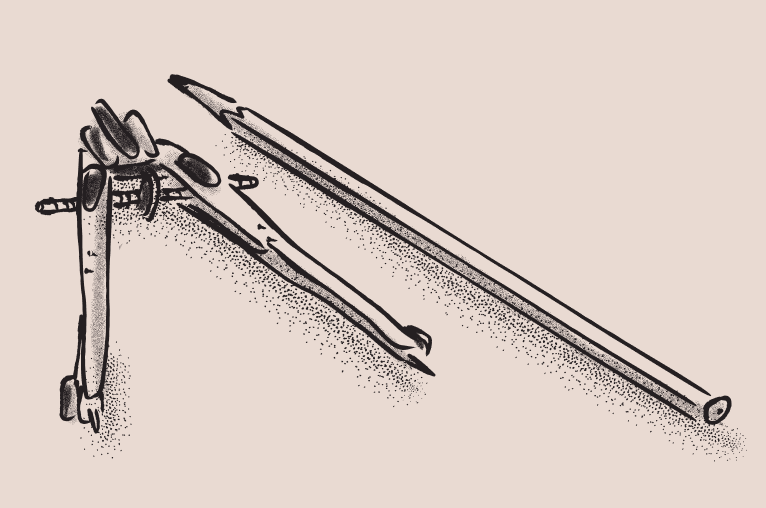

The structural nature of corruption, its ever-widening gyre, is an abyss terrifying to look into, let alone to attempt to distill in its entirety. This is the courage in Lombardi’s work— its bare, skeletal testimony to enduring relevance. We are still, as Greg Stone averred, living in Mark’s future, and it is indeed fucked up, but we are always in need of more like him: those willing to use the simplest tools: paper, pencil, compass, line, words, and sheer stubborn time— to force shapes on the amorphous and render legible that which would prefer to stay hidden. Simple devotion, after all is done, often proves to be supreme grace in the dark.

.png)